This is a summary of an average 🌿 branch book. If you are interested in applying deliberate practice to your life, Peak is only worth a skim — preferably using Bregman’s method for speed reading. Read more about book classifications here.

Professor K. Anders Ericsson has had a very accomplished career studying the forms and origins of expertise. Early in his life he worked under renowned polymath Herbert Simon, and studied what could be gained from ‘think-aloud protocols’ — a fancy name for the psychologists’s technique of asking a subject to solve a problem while describing their thinking. Later, Ericsson used exactly those think-aloud protocols to study the pursuit of expert performance. As a result of his work, we now have a body of research dedicated to the understanding of ‘deliberate practice’ — the type of practice best shown to lead to expert performance.

Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise is a 2016 book that summarises three decades of research into the nature and development of expertise. Ericsson wrote the book partially as a response to the often-quoted ‘10,000-hour rule’, which was popularised by Malcolm Gladwell in his 2008 book Outliers (the ‘rule’, per Gladwell, was that you needed a minimum of 10,000 hours to get good at any skill). This was a misrepresentation of Ericsson’s work; he later published an excerpt from Peak on salon.com to rebut the claims from Outlier.

I am hesitant to recommend Peak to the layman, except as a first step to the world of deliberate practice. It’s true that we should attempt to read books that are written by authorities — my entire ‘epistemology of practice’ essay was written as an argument to take believable experts more seriously. And some may say that Ericsson is the authority on deliberate practice — making his book the definitive guide to the research.

But Peak side-steps some of the more interesting developments in the deliberate practice world. In particular, it stands defiantly against the increasingly mainstream (though somewhat troubling) view that genetics has some role to play in the kinds of things that psychologists study — expertise and personality amongst them. Ericsson’s claims that innate talent is overrated and that much of expert performance may be explained by quality of practice alone has come under attack in recent years; as I’ve written elsewhere, my take is that Ericsson’s view of ‘practice, above all else’ would likely not survive the next decade.

But let’s set that aside for now and examine the core of Ericsson’s book: what, exactly, is deliberate practice? How do we use it in our lives?

Other Types of Practice

Peak opens with a description of the other forms of practice: that is, naive practice and purposeful practice. Ericsson argues that both forms of practice pale in comparison to deliberate practice, but mentions that we can learn quite a bit from studying them before we turn to DP.

Naive practice is the act of doing something repeatedly, with the belief that mere repetition would improve one’s performance. This is, of course, misguided: as programming instructor Kathy Sierra puts it: “Practice doesn’t make perfect. Practice makes permanent.” Repeatedly practicing subpar technique results in that technique becoming instinctive and habitual. The worst thing you can do for your progression is to keep doing subpar things the same way again and again — it signals to your brain “Remember what you’re doing now! Do this forever!” and dooms you to mediocrity.

Purposeful practice, on the other hand, is a form of practice that begins to approach deliberate practice in effectiveness. Ericsson started his career studying forms of purposeful practice (in the context of memory competitions in the 80s) and describes it this way:

- Purposeful practice has to be focused. You should not be able to think of anything else while undertaking it.

- Purposeful practice should take you out of your comfort zone. It should feel painful to do. So: putting on a musical performance of pieces you’re already good at does not count, and writing a program that utilises techniques you already know isn’t useful. Practice that makes you better should take maximal effort, and should therefore feel terribly unpleasant to do.

- Purposeful practice requires feedback, and adjustments to technique after getting the feedback. In its most general form, Ericsson notes that feedback need not be immediate — but it is most effective if the feedback loop is short.

- Purposeful practice has well-defined, specific goals. You don't want to "play this musical piece", you want to "play the complicated second section that requires unorthodox finger placement". You don't want to "code iPhone apps" you want to "implement the nested MVC model from scratch".

If you’re like me, you’re probably looking at this list of properties and thinking to yourself: “Man, this certainly looks like it should work. So why is it worse than deliberate practice? What are the problems?”

Mental Representations and Adaptability

Ericsson argues that the core problem with purposeful practice is that of knowledge. Or, to put it concretely: purposeful practice is self-directed (by definition), and unable to benefit from a long history of skill+pedagogical development.

The argument unfolds like so: first, Ericsson asserts that expert performance is determined by mental representations. It doesn’t matter if we’re talking about piano or Judo, tennis or chess, ballet or violin. An expert’s ability to perform well depends on the effectiveness of the representations she holds in her head (coupled with physical training in the case of sports, of course). As Ericsson writes:

Because the details of mental representations can differ dramatically from field to field, it’s hard to offer an overarching definition that is not too vague, but in essence these representations are preexisting patterns of information—facts, images, rules, relationships, and so on—that are held in long-term memory and that can be used to respond quickly and effectively in certain types of situations. The thing all mental representations have in common is that they make it possible to process large amounts of information quickly, despite the limitations of short-term memory. Indeed, one could define a mental representation as a conceptual structure designed to sidestep the usual restrictions that short-term memory places on mental processing.

Some of you may notice that this description is conceptually equivalent to the whole ‘mental model’ shebang. The purpose of practice, then, is to build better mental representations of the specific skill in question — be it fine motor control in the case of a violinist, or position analysis in the case of a chess player.

Here, the memory champions that Ericsson worked with in the 80s differed from practitioners in ballet, violin and chess in one key aspect: the former competitors had to develop effective mental representations on their own . Ericsson notes that some of them developed subpar mental representations; others developed better ones, and still others chose to pass those better representations on. Years later, the development of modern ‘memory palace’ techniques allowed competitors to successfully memorise numbers with 300 digits. Ericsson draws a long line from the early attempts, when no memory coaches existed, to the state of the field today ... where better mental representations are known and better training methods have been developed to pass those representations on.

Ericsson thus argues that the most effective form of practice — deliberate practice — can only exist in fields with developed mental representations and relatively sophisticated pedagogical techniques. It is in these fields that he has staked his entire research career: the theory of deliberate practice was developed by studying pianists, violinists, swimmers, golfers, ballet dancers, and chess players, all of whom benefit from decades of skill development, handed down from generations of coaches and players.

What is it that practice does to your brain when you are developing improved mental representations? The answer, of course, is the concept known today as ‘neuroplasticity’ (which Ericsson calls ‘adaptability’):

(…) in most parts of the brain the changes that occur in response to a mental challenge—such as the contrast training used to improve people’s vision—won’t include the development of new neurons. Instead, the brain rewires those networks in various ways—by strengthening or weakening the various connections between neurons and also by adding new connections or getting rid of old ones. There can also be an increase in the amount of myelin, the insulating sheath that forms around nerve cells and allows nerve signals to travel more quickly; myelination can increase the speed of nerve impulses by as much as ten times. Because these networks of neurons are responsible for thought, memories, controlling movement, interpreting sensory signals, and all the other functions of the brain, rewiring and speeding up these networks can make it possible to do various things—reading a newspaper without glasses, say, or quickly determining the best route from point A to point B—that one couldn’t do before.

It isn’t necessary, I think, to discuss the neuroscience that underpins practice. It should be enough to know that the brain changes in response to effort, and that proven pedagogical techniques are more effective at prompting such changes. With this foundation in place, Ericsson finally tackles deliberate practice directly.

Deliberate Practice

Deliberate practice picks up where purposeful practice left off, but adds a small number of additional properties:

- First, it demands that the practice be conducted in a field with well-established training techniques. Fields like music, math and chess have rigorous training methods that have been developed over the course of decades. This makes such fields ideal candidates.

- Second, it demands that practice be guided in the initial stages by a teacher or coach. Good mental representations are needed for effective self practice. A student may eventually develop the necessary mental representations to practice on her own … but a coach is necessary for development of proper mental representations in the beginning.

- Third, deliberate practice produces and depends on effective mental representations ... basically, a virtuous cycle. As hinted at by the second property — improving performance means improving mental representations; as one’s performance improves, the representations become more nuanced and effective, thus making it possible to improve further.

- Fourth, deliberate practice nearly always involves building or modifying previously acquired skills — by focusing on particular aspects of those skills and working to improve them individually. This means finding teachers or coaches with ever higher levels of expertise, dropping ones that are lousier as you move up the ladder to mastery.

The implication here is that if you aren’t in a field with developed methods, you’re fresh out of luck. To his credit, Ericsson pauses and says that you may still ‘apply the principles of deliberate practice’ in fields without such developed methods:

(…) the basic blueprint for getting better in any pursuit: get as close to deliberate practice as you can. If you’re in a field where deliberate practice is an option, you should take that option. If not, apply the principles of deliberate practice as much as possible. In practice this often boils down to purposeful practice with a few extra steps: first, identify the expert performers, then figure out what they do that makes them so good, then come up with training techniques that allow you to do it, too.

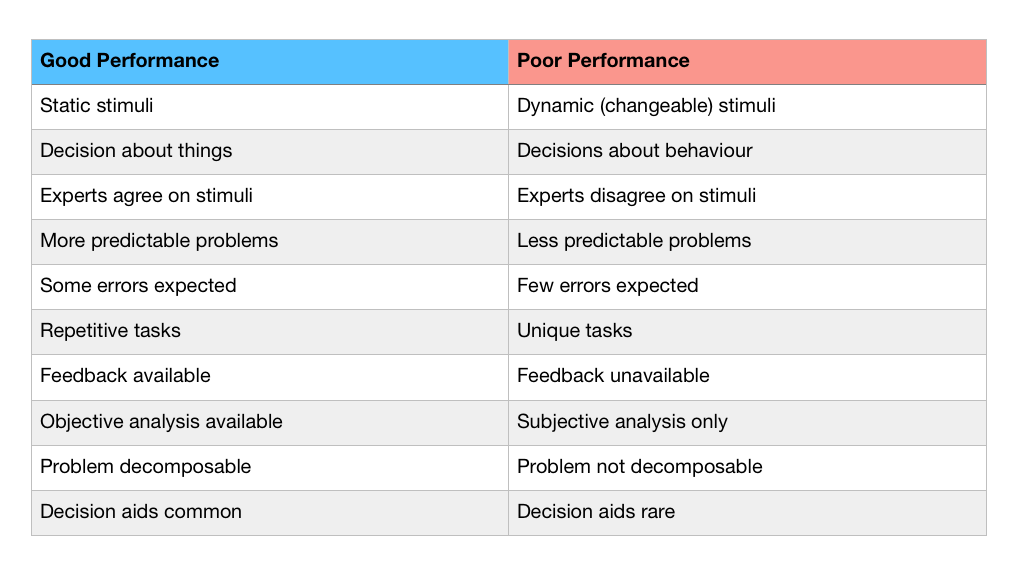

Of course, this comes with several caveats. The most important one is that you should be in a field where expertise is possible. As I’ve covered in Part 4 of my Framework for Putting Mental Models to Practice, there are fields where good expert performance is possible, and fields where it isn’t; the fields that are bad are maliciously structured to thwart development of expertise:

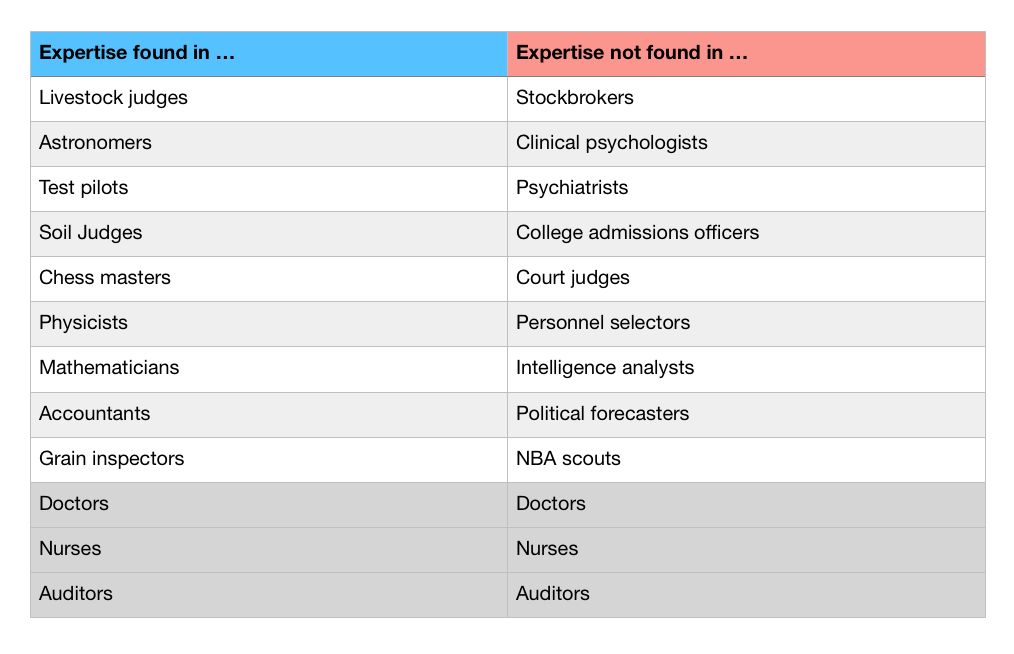

If we turn those to examples, we find the following list of professions in which expert performance is possible on the left, and where it isn’t on the right:

Ericsson doesn’t deal with this problem beyond ‘identify that the expert you are studying actually has expertise’, along with a five-second tour of the cognitive biases and heuristics literature. You’ll do better to read Kahneman and Klein in their 2009 paper on the conditions for expertise — if expertise is possible in your field, turn to deliberate practice. If it isn’t, then the training techniques you’ll have to use would look very different; this is one reason I don’t recommend Peak as anything but an introductory text for the determined practitioner.

Stories of Deliberate Practice

One of the more interesting things about Peak are the stories of actual deliberate practice training programs in action. These stories tell us what it actually looks like to design or partake in an Ericsson-approved, deliberate practice-inspired training program, which is in turn important because deliberate practice is ridiculously difficult to apply. In chapter 5, Ericsson tells us the story of the Top Gun training program, and concludes:

It is never easy to design an effective training program, whether for fighter pilots or surgeons or business managers. The navy did it mainly through trial and error, as you find when you read histories of the Top Gun program. There was a debate, for instance, over how realistic the combat had to be, with some wanting to dial it back and lessen the risk to the pilots and the planes, and others arguing that it was important to push the pilots as hard as they would be pushed in real combat. Fortunately, the latter viewpoint eventually prevailed. We know now from studies of deliberate practice that the pilots learned best when they were pushed out of their comfort zones.

It has been my experience that there are many, many areas in the working world today where the lessons learned from studies of expert performers can help improve performance—in essence, to design Top Gun programs for different fields.

That's all well and good, but ideally what I'd like to see is “a practitioner’s handbook to creating deliberate practice programs through trial and error”. The closest we can get to that are stories of actual deliberate practice in action, and on this front Peak does reasonably well.

Take chess, for instance. For the longest time I thought chess players practiced by playing full games. Ericsson points out that they do not; such games take too long to play and therefore don't make for very good practice. Instead, what most chess players do is that they analyse a specific chess position — perhaps from a famous game by a grandmaster — and attempt to predict the grandmaster’s next move without referring to the actual game. After taking the move, they would check to see what the grandmaster actually did; if the move differed from the grandmaster’s, they would circle back to figure out what they’d missed.

That's just one example. There are others.

Benjamin Franklin got good at writing by picking articles from The Spectator, summarising them, and then attempting to recreate the original piece from the written summary. The comparison between the two pieces would serve as feedback; the fact that Franklin could easily correct the deficiencies in his writing as compared to The Spectator’s version meant that he did not need a teacher. Ericsson points out that Franklin later became one of the most successful writers in America (in addition to, urm, a few other things).

Writing from a summary wasn’t quick enough for Franklin when it came time for him to work on the structure of his writing. This time, he took Spectator articles and wrote hints on separate pieces of paper, before jumbling them up so they would be completely out of order. After waiting a period to ensure he had forgotten the structure of the original article, he would return and try to reproduce the articles, this time by rearranging the hints and turning them into prose. Finally, he would compare the two pieces — the original piece from The Spectator alongside his reconstructed attempt. Whenever he noticed places where he had failed to be as clear as the original writer, he would correct his work and try to learn from his mistakes.

The American swimmer Natalie Coughlin describes how in her early swimming career she would spend most of her practice time daydreaming. She later realised that she was squandering a major opportunity during the hours she spent in the pool — instead of letting her mind wander, she started focusing on her technique, trying to make each stroke as close to perfect as possible. It was only when she started doing this that she really began to see improvement in her times … and the more she focused on her form in her training, the more success she had in competition. From this story Ericsson concludes that even in ‘repetitive’ sports, mental engagement matters for improvement. Don’t let your mind drift during practice.

In Berlin, Ericsson noticed that the violinists he studied found practice so tiring that they would often take a midday nap between their morning and afternoon practice sessions. He took this to mean that high intensity practice for short periods worked better than longer, lower intensity practice sessions. Later on, when a man named Per Holmlöv approached Ericsson for advice on developing a deliberate practice program for karate, Ericsson advised him to reduce his practice sessions — to go for shorter, one-on-one training sessions at a higher level of concentration, instead of the multi-hour classes he had been attending. Holmlöv’s rate of improvement started increasing soon after.

A student in an ESL (English as a second language) class went to a mall and stopped a number of shoppers, asking each the same question. This way, she could hear similar answers over and over again. This repetition made it easier for her to understand the words spoken by native speakers at full speed. She wasn’t simply doing the same thing repeatedly; she was paying attention to what she got wrong each time, and correcting it.

My point is that such stories deliver the bulk of the value for the practitioner. I can already imagine that some of you are inspired by the stories above — you may have noticed certain ideas in them that you now wish to apply to your own lives. This is as it should be.

My personal takeaway? Whenever possible, find ways to increase the speed of the feedback loop and the intensity of the practice. Don’t write full essays, write short segments with feedback. Don’t write full programming side projects, write throwaway prototypes to learn specific programming techniques.

Takeaways

I’ve left out summaries of two chapters in Peak — the first being the chapter where Ericsson argues that talent is overrated, and the second a chapter covering what is known about the development of world-class experts from childhood to adult. I’ve chosen, as always, to focus on what is useful to the practitioner, and I think such arguments are — while interesting — not immediately useful.

(Diving into the argument of talent vs practice is not something I want to get into here, but I will say that Ericsson doesn’t mention any of the more recent objections to his work in Peak. For an overview of those arguments, it’s probably worth checking my other essay Problems With Deliberate Practice, with the caveat that the debate isn’t particularly useful to a practitioner.)

What can you learn from Peak? Overall, I think Ericsson has done an ok job of introducing the layman to the field of deliberate practice. To recap: practice works because the human brain is adaptable, and because performance is determined by the quality of our mental representations. Naive practice is bad; don’t do it. Purposeful practice is all we have if we are to work in a field with no developed training methods. Deliberate practice exists where fields are well developed, and require a teacher to execute well. Creating deliberate-practice-inspired training programs are extraordinarily difficult, and you should expect such efforts to be doable only with extended trial and error.

But what Peak fails to do is to provide a complete guide on how to put deliberate practice into … well, practice.

I’m aware that my summary of Peak is tinted with my frustrations of the deliberate practice tradition. This is through no fault of Ericsson’s; in fact, I admire him for building this body of knowledge for us to use. But as a practitioner, I have had great difficulties putting deliberate practice to practice, and I wish there existed a book that tackled the challenges of this head on. In fact, the most helpful person I’ve talked to about putting DP to practice has been an education consultant who now works for Pivotal Labs in San Francisco — he’s been experimenting with putting DP to use in writing and programming training programs for a number of years now, and admits that it’s a lot harder than he initially thought it would be. Until this person (or a similar person, engaged in similar things) writes a book, we’re probably left to our own devices.

To be fair to Peak, much of my frustration is tinted by the online resources available on deliberate practice. The vast majority of the blog posts I’ve read on DP have been rather vague — nearly everyone who writes on the topic acts as if ‘it is known’ that DP works, and that putting it to use in one’s life is trivially easy. It is not, and it wasn’t until reading Peak that I realised why: the principles of deliberate practice are easy to state, but the methods of applying them to a training program demand a level of creativity that require sustained effort to achieve. (I’ve written about some of these challenges in my previous essay on DP).

I think the primary takeaway here is that deliberate practice is probably the best known way to get good at something, but that it is incredibly difficult to put into practice. I think there is real value to a resource that collates all successful stories of putting DP to practice, as a reference for those of us who wish to put it to use in our respective fields.

Till then, reading Peak is probably no more nor less than a good first step.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→