This is Part 5 of a series of posts on putting mental models to practice. In Part 1 I described my problem with Munger's latticework of mental models in service of decision-making after I applied it to my life. In Part 2 I argued that the study of rationality is a good place to start for a framework of practice. We learnt that Farnam Street's list of mental models consists of three types of models: descriptive models, thinking models concerned with judgment (epistemic rationality), and thinking models concerned with decision making (instrumental rationality).

In Part 3, we were introduced to the search-inference framework for thinking, and discussed how mental models from instrumental rationality may help prevent the three types of errors as implied by the search-inference framework. We also took a quick detour to look at optimal trial and error through the eyes of Marlie Chunger. In Part 4, we explored the idea that expertise leads to its own form of decision making. The key takeaway from that is that rational decision making falters in domains where expertise is possible. Or to put it another way: don’t read general mental models if you haven’t gained sufficient expertise yet!

In Part 5, we discuss building expertise in service of making better decisions. What does this mean? What does the field of naturalistic decision making have to say about getting better at it?

Let’s begin this essay with a simple question: what, exactly, is a mental model?

In teaching, a mental model is merely a ‘simplified representation of the most important parts of some problem domain that is good enough to enable problem solving’. (I’ve stolen this definition from Greg Wilson’s book Teaching Tech Together here). This definition is useful to us because it is an instrumental one — that is, the definition helps clarify the role of mental models in learning. In Wilson’s case, a teacher’s job is to help the student construct usable mental models in order to write computer programs. In this series, we are interested in acquiring mental models that help us make better decisions in service of achieving our goals.

If this definition sounds familiar, it is because it is: Wilson’s definition is very similar to the one used by Farnam Street:

Mental models are how we understand the world. Not only do they shape what we think and how we understand but they shape the connections and opportunities that we see. Mental models are how we simplify complexity, why we consider some things more relevant than others, and how we reason.

A mental model is simply a representation of how something works. We cannot keep all of the details of the world in our brains, so we use models to simplify the complex into understandable and organisable chunks.

The reason I’m bringing this up is to point out that mental models aren’t some special thing that only exists in Farnam Street’s list. Shane himself has done a good job of defining mental models, but I’ve noticed instances where people use the phrase ‘mental model’ to mean only the descriptive models referred to by Charlie Munger in Elementary Worldly Wisdom. I’ve also observed people using ‘mental model’ when ‘framework’ would’ve been a better word.

It’s probably worth reminding ourselves that mental models mean something far broader in the original psych literature. In that corner of academia, mental models are considered the basic building blocks of all learnt knowledge. Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development, for instance, explains how a child constructs a mental model of their world. Piaget asserts that through a mix of biological maturation and environmental experience, children gradually build richer models for navigating reality — for instance, learning to grasp objects, learning to crawl, learning to walk without support, and then learning to manipulate fine objects and to interact with other human beings.

By this definition, mental models aren’t something that we can choose to use. They’re not a ‘thinking style’. They are at the very heart of how we function as human beings. This definition matters because we’ll be spending this essay talking about acquiring tacit mental models from the domain around us, in service of making better decisions.

Domain Specific Mental Models

Let’s talk about the sorts of mental models we build in our careers.

Joe is a software engineer. In his first week of work, he observes a flickering fluorescent tube in the corner of his office. Annoyed by the flicker and impatient for janitorial staff to come fix it, he procures a replacement tube from the supply closet and grabs an office chair. Seeing a man in a formal suit walking by, he calls out to him: “Hey, would you mind holding this chair steady while I change this light?”

Joe changes the tube, thanks the man, and goes back to work. Much later in the day he discovers the man was actually the CEO of the company, and it was he that Joe requested to help hold the chair. Joe is mildly embarrassed, but remembers the man’s face. As a result, Joe has updated his mental model of the company’s org chart.

This organisation-focused, domain-specific knowledge is also a mental model. Over time, Joe will fill in more faces and attach them to positions in the company’s org chart. He will begin to learn about the political factions that exists, the people that occupy each faction, and on which issues they disagree over. He will begin to construct richer mental models about the way information flows within the company, the leverage points that he may use to get what he wants, and the larger concerns of his manager, his manager’s manager, and his department in relation to the rest of the corporation.

These sorts of mental models are ones that we intuitively build as we progress in our careers. They're also incredibly important to our effectiveness. For instance, your success as a manager or corporate decision maker will often require you to read shifting organisational winds — an ability you must develop. Unfortunately, the mental models that allow you to do so are not something that you can easily find in a book; nor do they tend to be general. You’ll have better luck watching more experienced hands in your company.

This doesn’t seem like a very controversial statement to make, though. Of course specific mental models will beat out general ones when it comes to performance in a specific domain. The question that interests me is the meta one implied here: is it possible to get better at acquiring these domain-specific, expertise-oriented mental models — even if the types of mental models that we’re talking about are the ones that make you more effective at company politics?

Klein and others suggests that it is. His key observation is that because expertise depends on experience, building up a store of meaningful experiences is key to shoring up your ability to use RPD. That said, while real-world experience is the best form of experience, it is not an ideal teacher. Many of us do not get the opportunity to accumulate enough real experiences in a particular field in service of developing expertise; to make things worse, many of us do not have the luxury of waiting until we’re doing something for real to learn from our mistakes. You don’t really want to make a bad move in your organisation, for instance, for all the damage that might do to your reputation. So how do you get savvier?

Klein argues that we should adhere to two common-sense principles: first, we must find substitutes for real-world experience for the specific subskills where we can’t practice in the real world. Second, we must get the most out of every experience that we are able to get.

His strategy for developing expertise-driven decision making, then, is four-fold:

- First, identify discrete decision points in one’s field of work. Each of these decision points represent discrete areas of improvement you will now train deliberately for.

- Second, whenever possible, look for ways to do trial and error in the course of doing. For instance, run smaller, cheaper experiments instead of launching the full-scale project you’re thinking of. Look for quick actions that you may use to tests aspects of your domain-specific mental models. This is, of course, not always possible. Which leads us to —

- Run simulations where you cannot learn from doing. Klein and co have developed a technique for running simulations called ‘decision making exercises’, or DMXs. The DMX style of decision training was originally developed for Marine Corps rifle squad leaders and officers in 1996. It is still in use for squad leader training; the version I describe here has been adapted by Klein for corporate decision makers.

- Fourth, because opportunities for experiences are relatively rare, you should maximise the amount of learning you can get out of each. Klein has specific recommendations for decision-making criticism, though it won’t surprise you to hear that these are very similar to existing recommendations for after-action reviews. We will mention this only in passing.

The purpose of this essay is to give you an idea of the overall approach the field of Naturalistic Decision Making has taken to decision training. The training methods here were originally designed for the US Military, but have been adapted for emergency room nurses, fireground commanders, managers and executives. I will leave out a lot of nuance, sacrificing detail for broad strokes. My recommendation here is to go out and purchase a copy of The Power of Intuition — nearly every chapter is actionable, and Klein provides far greater detail for each of the techniques I’m going to cover.

To give you a taste of what a decision-making simulation looks like, and to perhaps convince you that there’s something to this, let’s consider the following decision game that Klein has developed for his corporate practice, outlined in The Power of Intuition. I’ve taken the liberty to adapt this exercise to Joe’s story.

Joe’s Challenge

Three years after we first met Joe, we find him settled into the company as a senior project manager. The company has recently downsized due to an economic downturn. Because overall workload has gotten light, the CEO has decided to turn this into an advantage by proceeding with some internal research and development. Joe submits an idea for a project to develop a new type of business database that may be accessible through mobile phones; this proposal is given high ratings and Joe is told to start work. He is given eight months because the CEO believes the lull in work to be temporary. Joe is excited by this opportunity. He believes that it would give him better visibility within the company; motivated by this belief, he begins to gather his team.

Joe is given the full-time services of a staff of 12 people including himself. He has six people from his department, plus two human factors specialists on loan, plus another three communications specialists, also on loan. In addition, Joe arranges for a key piece of software to be developed by the company’s software team.

What follows is a series of events that unfolds over the course of the next couple of months. Your task is to read each event in sequential order (don't skip ahead!). As you do so, mark down on a piece of paper or in a text editor which of the events appear significant to the successful completion of Joe’s project. Put yourself in Joe’s shoes: what would you do in response to the events that appear significant to you? How can you ensure the best possible chances of success for the project? Jot those thoughts down.

The events:

- A competitor has announced the near completion of a product that in some ways is similar to Joe’s.

- An additional twenty layoffs are announced for Joe’s company, but none of these is from his team or his group.

- The president of the company announces a hiring freeze that is absolute and (hopefully) temporary.

- An experienced marketing executive tells Joe that she is dubious about the competitor’s announcement. They have made similar claims about vaporware in the past. Her inside sources hint that they’re just trying to discourage others from moving into this area.

- Good news! The company wins a large contract with an insurance company to increase the usability of links from the Web to customer service.

- Joe’s project is now starting on its third month and is on schedule.

- Good news! The company announces that a new contract has been signed for a project to develop software for a major bank.

- A different competitor has just hired some of the former employees of Joe’s company who had been laid off a few months earlier.

- The company’s financials show a lot of red ink — it lost a fair amount of money in the preceding quarter.

- Rumours are circulating in Joe’s office that the parent company is unhappy with the revenue picture. Some of Joe’s office mates are speculating that the CEO may be replaced soon.

- Good news! Another large new contract is signed, with work set to begin in the next month. Many people — Joe included — begin hoping that this signals a turnaround for the company.

- Joe hears from a friend in HR that the management information systems department requested a waiver of the hiring freeze, but was denied.

- Two people from Joe’s department announce their resignations. They each describe different reasons, but others suspect that the revenue uncertainty is taking its toll. Neither of the people are from Joe’s project team.

- Joe receives a company-wide email announcing that there will be a move in the next three months to a new office complex, as a way to cut costs.

- Joe seeks and receives reassurances from upper management about the long-term importance of his project.

- Joe’s project is starting its fourth month and is on schedule.

- Joe is informed that the software group may be unable to deliver the programs that the project needs. The task is more difficult than expected.

- The communications systems specialists complain to you that they are getting pressure to work on the new contracts that have just come through, because those will generate revenue.

- Joe hears from a secretary that the problem with the software program was that the developers were being pulled into the bank software effort, and that’s why they are lagging in delivery.

- Joe overhear’s a lunchroom discussion about how company leadership is actively considering rescinding the hiring freeze.

- Joe has a productive meeting with the software group. He’s able to reduce the number of required features so that they may stay on schedule.

- The project is now in its fifth month, and is falling behind schedule, though the reduced features that Joe has negotiated makes it a little difficult to estimate.

- The human factors specialists on Joe’s team have missed the last two meetings. They say that they’re being on-boarded for the insurance company usability project.

- A senior VP announces she’s taking early retirement.

- The financial department begins releasing daily graphics showing revenue curves are heading up again.

- Joe’s manager tells him that over half of the project team is being reassigned to projects for clients, to increase revenue. Joe is losing both human factors specialists, all three communication specialists, and two database specialists. Joe is asked to wrap up the project by using the remaining personnel to document progress, so that the effort can be shelved until the financial picture improves.

Now: look back over your notes. Did you see this coming? At which point did you realise that the project was doomed?

This situation is unfortunately all-too-common in the real world. Each move made by upper-management is frustrating and damaging to company morale, but ultimately understandable. It is event 26 that crushes Joe’s project, forcing him to wrap things up with little to show for his efforts.

When Klein started administering this decision game, he found that many people caught on to the potential problems by item 23 or item 19. One person wrote next to item 17 “this is the first major hitch”, and later “things are now unravelling” next to 18, and “major problems” next to 19.

The most experienced executives that played this game, however, had uneasy feelings from the very beginning (around items 5 and 7). These executives saw the contradiction between starting an internal project to use surplus labour while downsizing to reduce the labour supply. They picked up on the implications of the hiring freeze in item 3, and predicted that people were going to be pulled out from the project when new contracts were announced (items 5, 7, and 11). When two of Joe’s colleagues quit (item 14), they surmised that this would further intensify the labour shortage.

In this situation, identifying potential problems earlier gives you more room to manoeuvre. If Joe had the experience of the more capable executives, he might have recognised potential problems months in advance, and taken commensurate actions in response. For now, let’s pause to ask: could you see yourself in Joe’s shoes? What have you learnt from this experience?

This DMX works by simulating experience without actually having to have the experience. I enjoyed this format immensely because I could put myself in Joe's position, and I could experience the decision-making process as it occured. I could even imagine this scenario happening in my company. What lessons are contained in this DMX? Well, apart from an appreciation of the relationship between internal resource availability, revenue, and the importance of office gossip, Klein’s game teaches you the types of ‘seeing’ needed to do well in a similar situation. This particular scenario has now become part of your store of experience.

Here we arrive at the actionable question: how do we create, apply, and deploy this technique?

Identifying and understanding decision points

The first observation is that we can rather easily create DMXs from our own experiences — that is, for training purposes. This has the added benefit of having DMXs that are adapted to your unique environment. In Part 4 I mentioned that I failed to teach my HR exec the mental models that I used to navigate my company’s growing demands; I see now that I could have done this by devising a series of DMXs — drawn from company history — to demonstrate the relationships between each department.

Klein points out that DMXs built from a real world scenario often converges on whatever action it was that was taken in real life. This is often considered the ‘right answer’. This isn’t ideal; in most situations, you want an open-ended game with no correct answer to allow for an energetic exchange of opinions. The actual decision is less important than the simulated experience of thinking through the situation.

One technique that I’ve found quite useful is NDM’s approach to identifying decision points. Klein says to identify a bunch of key, challenging decisions that you have to do as part of your work. For example, a manager at my company might identify the following decision points:

- Estimating timelines for a given project.

- Selecting one supplier over another.

- Hiring or promoting people.

- Assessing whether a project is derailing and if so, if it’s prudent to interfere.

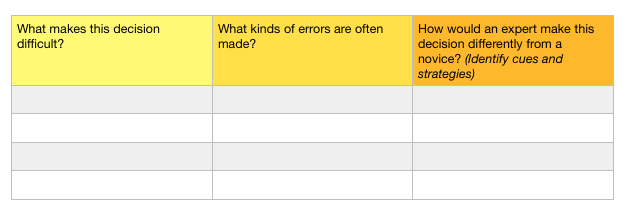

For each decision, fill in the following ‘Decision Requirements’ table:

The table requires you to answer three questions, though Klein encourages practitioners to adapt the questions to their situations. To illustrate, the aforementioned manager might write the following for ‘estimating project timelines’:

- Decision Point: “How do I estimate project timelines accurately? I seem to get blindsided by unexpected problems, even with buffer time in the project plan.”

- What makes this decision difficult? There are no simple rules for estimating time/effort requirements. There are also often competing goals, of which timeline is but one. Also, I cannot predict the nature of unpredictable problems.

- What kinds of errors are often made? I tend to be overly optimistic. My buffer times are never enough when unexpected problems occur. I am reluctant to reduce project scope, because stakeholders.

- How would an expert make this decision differently from a novice? (Identify cues and strategies) I notice Kevin seems to have a good track record as a project manager. He appears to know just how much buffer time to include in an estimation. He’s also delivered on time for most of his projects last year. He appears to have better luck when negotiating for reduced project scopes. I’m not sure how he does some of these things.

There are three things I’d like to highlight here. First, any difficult decision that you encounter in day-to-day work can be turned into a DMX. It may be useful to run these DMXs with colleagues or peers — keep the decision game simple; use paper and pencil; make sure it lasts no longer than 30 minutes … perhaps over lunch. Again, the primary benefit is to experience these simulated situations together.

Second, thinking about the kinds of errors that are often made in difficult decisions will usually yield a few actionable ideas. For example, when asked for potential approaches to the above decision problem, the manager suggested that she could check her optimism by keeping a ‘tickle list’ of common project issues that we’ve experienced together. She also said that she would “talk to Kevin”.

It’s this last option that I find particularly interesting. The third question in Klein’s Decision Requirements Table exists to prod you into observing the expertise of those around you. Klein’s supposition is that the mental models you require for good expertise-driven decision making is likely to already exist in the heads of the people around you. In order to acquire those mental models, you’ll need something that is marginally more sophisticated than “ask them how.”

Skill extraction (or, ‘The Critical Decision Method’)

What happens when you ask an expert how he or she accomplishes a task? It’s likely that you already know the answer to this: the practitioner is probably going to say something along the lines of “it felt right”, or “I just knew what to do!” That isn’t useful to you.

Thankfully, Klein and his collaborators have developed a technique for extracting tacit mental models of expertise. Their overall approach is known as Cognitive Task Analysis, and the specific method that is of interest to us as practitioners is known as the ‘critical decision method’, or CDM. This method requires some skill to use, but the simple form as relayed by Klein in Sources of Power is practical enough for us to attempt to apply.

The setup for CDM is to use the human instinct for storytelling to elicit mental models from the expert practitioner. Don’t ask how they did it — ask what happened, and then use cognitive probes to tease out their models.

The Recognition-Primed Decision Making model that we covered in Part 4 gives us a map for what we’re looking for. An expert recognises a situation via pattern-matching and generates four by-products: expectancies, cues, goals, and an action-script, and then simulates the actions to see if it is applicable. For the sake of simplicity, we may reduce this to:

- Cues let us recognise patterns.

- Patterns activate action scripts.

- Action scripts are assessed through mental simulation.

- Mental simulation is driven by mental models.

In this simplified view, the elements that are most accessible to us are the cues and the action scripts. If you don’t have time to probe for all four by-products, then focus primarily on the cues and the actionable strategies that the expert uses. From my experience in applying this, these two bits are often enough to provide hints as to the shape of the tacit mental models that exists in our expert’s head. CDM goes as follows:

- The first step is to find a good story to probe. The story might be non-routine, where a novice might have faltered. Or it could be about a routine event that involves making perceptual judgments and decisions that would prove challenging to a less experienced practitioner. Klein notes that a good story should be about an event with multiple decision-points — that is, parts in the narrative where a practitioner might have selected one of a few different types of actions. In this first step, just ask for a brief summary of the story to see if it’s worth digging into. Of course — if you already know what stories are available because you work in the same company, then you may skip this step entirely.

- After such a story is located, ask for a front-to-back narrative of the event in question. As this occurs, keep track of the state of knowledge and how it changes as events occur. Note the situational awareness of each stage, and clarify the timeline of events if necessary. In Klein’s experience, this part is usually the easiest — practitioners like to tell stories about displays of skill, and other practitioners tend to want to listen in.

- The third pass is to probe for their thought processes. At this point Klein’s team will usually ask what a person noticed (cues) when changing an assessment of the situation and what alternate goals might have existed at that point. If your practitioner chose a course of action, ask them what other actions were possible, whether they considered any of them, and if so, what the factors were that favoured that option. Make time to generate hypotheticals — for instance, if they had not had access to a key piece of information, what would they have done instead? If an event had not happened, what could explain such a thing? Hypotheticals are how Klein’s team pin down the shape of the mental models that power these decisions.

- If time permits, Klein will then do a fourth and final pass. This time, at each decision point, he would ask for mistakes that a novice could make. For example: “If I were the one making the decision, if by some fluke of events I got pressed into service during this emergency, would I see this the same way you did? What mistakes could I make? Why would I make them?” This probe is pretty useful for eliciting information on cues that an expert would notice but that a novice would not.

Of course, getting a verbal representation of this knowledge isn’t enough. In order to use it, you have to put it to practice. The goal of such knowledge is to guide the construction of tacit mental models of your own.

How do you identify expert practitioners to talk to? Sometimes this is easy: in naturalistic decision making, researchers rely on a history of successful outcomes. The most common method is to ask for peer evaluations, or, as Kahneman and Klein write:

The conditions for defining expertise are the existence of a consensus and evidence that the consensus reflects aspects of successful performance that are objective even if they are not quantified explicitly. If the performance of different professionals can be compared, the best practitioners define the standard.

In practice, if you are looking for an expert in your own company, you have an advantage: you are a peer, and you likely already know which practitioners are good at what tasks. Ray Dalio, however, has a useful notion called ‘Believability’ that he uses when reaching out to other practitioners for advice. I’ve found this quite useful, so I’m including this here:

Someone is defined to be believable if they have a record of at least three relevant successes, and have a good explanation of their approach when probed. Dalio’s application of this idea is the following advice-seeking protocol:

- If you’re talking to a more believable person, suppress your instinct to debate and instead ask questions to understand their approach. This is far more effective in getting to the truth than wasting time debating.

- You’re only allowed to debate someone who has roughly equal believability compared to you.

- If you’re dealing with someone with lower believability, spend the minimum amount of time to see if they have objections that you’d not considered before. Otherwise, don’t spend that much time on them.

I’ve found Dalio’s heuristic to be rather useful over the past year. If you think it makes sense, feel free to apply it to your search for expertise.

Decision Making Critique

The last part of Klein’s decision training is to engage in decision-making critique. On this, he recommends that you periodically review decisions that you’ve made with the following list of questions:

- What was the timeline? Write down the key judgments and decisions that were made as the incident unfolded.

- Circle the tough decisions in this project or episode. For each one, ask the following questions:

- Why was this difficult?

- How were you interpreting the situation? In hindsight, what are the cues and patterns you should have been picking up?

- Why did you pick the course of action you adopted?

- In hindsight, should you have considered or selected a different course of action?

Klein then suggests that you use this to identify decision points you need to practice further. This practice may happen with a DMX, or perhaps by actively arranging for specific types of work assignments.

Conclusion

I think the broad approach I’ve taken to putting mental models to practice has to go after expertise first, because my field warrants it. In this pursuit I have found that the most useful mental models are often in the heads of expert practitioners.

This essay provides an outline of techniques that one may use to identify and ‘extract’ skills from the domain that you inhabit. The goal, again, is in pursuit of ‘better decision making’; the approach that I’ve described depends on it being possible to build expertise in your chosen domain.

I have said in Part 1 that I believe that a latticework of mental models might matter if a) you are already an expert practitioner and you need an edge, or b) if you are in a domain where you need to perform rational analysis. I’ve covered the conditions for b) in Part 4, when discussing the nature of domains amenable to expertise. I’d like to deal with a) now.

I think it’s perfectly plausible for expert practitioners who are competing against each other to win based on the breadth of their knowledge. Certainly you need an edge from somewhere; acquiring mental models from a broad array of disciplines might augment your pattern-recognition or solution generation, as per the recognition-primed decision model. But as I am neither an expert practitioner, nor a practitioner in a field where expert intuition should be distrusted, I cannot say for certain. Check back in 10 years, when I am no longer merely competent.

I should probably highlight that I am not against books or reading. This very framework was constructed from synthesising books and papers, in pursuit of an organising framework that matched my experiences. I am not arguing against learning from ‘what other people have figured out’ nor am I arguing to ‘only learn from trial and error’. But I do believe that if we model at all, we should start from reality first and let it be the teacher, instead of modelling enthusiastically and trying to overfit reality to those models. I’ll talk about this in my next (and final!) part.

What I do disagree with is the central premise of Farnam Street’s approach to decision making: that is, the ‘best’ way to make good decisions is to acquire a broad base of ‘multi-disciplinary descriptive models’.

It isn’t the best way. It is certainly one good way, and it can be a worthwhile pursuit given one’s domain. But the approach to decision making that it inhabits is not the full picture that’s available to us. It isn’t very effective if you are a novice getting started in some fractionated field.

Acquiring mental models of expertise represent the other half of good decision making — and finding a balance between the two approaches appears to be the increasingly mainstream prescription of decision science (well, if Klein is to be believed, that is).

I hope this has been useful to you. I’d repeat my recommendation: buy The Power of Intuition and practice away.

Go to Part 6: A Personal Epistemology of Practice.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→