I’ve been using Get Things Done (15-min summary) on and off for a few years now — although only when I have to keep track of a large number of important projects in my life. I think the principles of GTD are more important than the method itself.

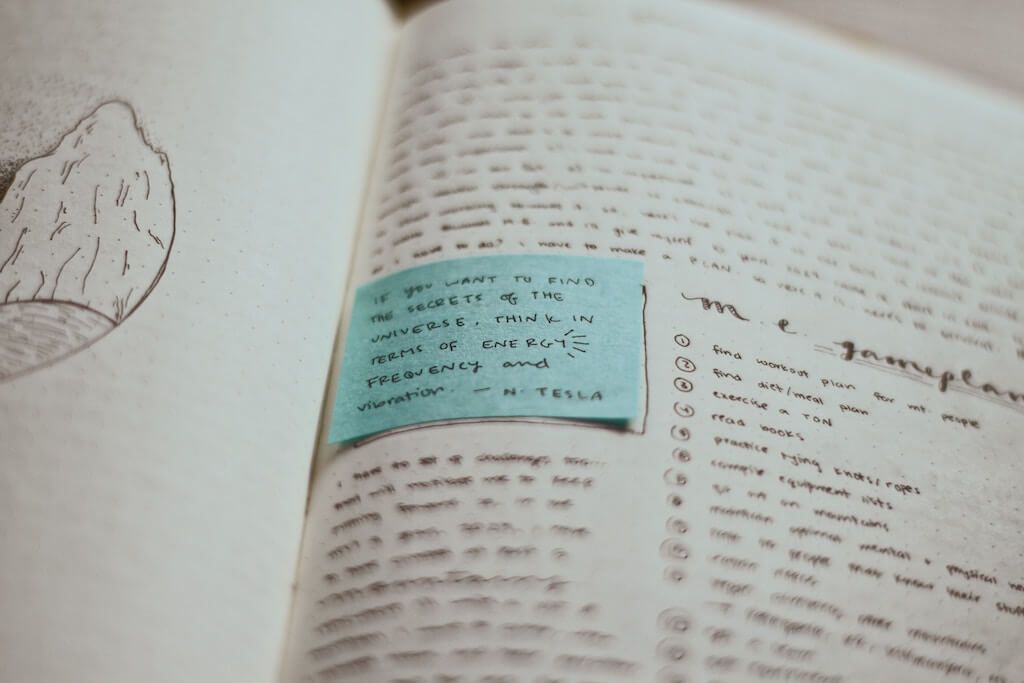

One important idea the system has is to do a personal review once a week, every week, preferably on a Sunday.

Why perform weekly reviews? GTD creator David Allen argues that the practice of any time management system will slip up, over time. With the weekly review, you are given an opportunity to clean up your existing task lists, in preparation for the week ahead.

More specifically, you are expected to:

- Go through each of the items in your Next Actions and Waiting For lists, to ensure that everything on those lists are actually things you want or need to do in the coming week.

- Look through your Someday/Maybe list and see if some projects or tasks should be moved to the list of current projects. Retire them otherwise.

- Go through your ‘tickle lists’ to see if there’s anything you’ve forgotten for the coming week.

I’ve been doing weekly reviews fairly consistently over the past couple of years, whenever I’ve seen fit to use GTD. Recently, however, I’ve been thinking about the fact that GTD works well for short-term time management, but doesn’t work so well for longer-term, career-strategy-type stuff. (I’ll also admit to being influenced by this Tiago Forte thread on task management; Forte has a very different take on GTD’s principle of total capture. I suppose having Forte as an example opened my eyes to the possibility of hacking GTD to my own ends.)

Two weeks ago, I was reading Lean Analytics by Alistair Croll and Benjamin Yoskovitz, when I came across the following section:

(…) By now, you’re a bigger organization. You’re worrying about more people, doing more things, in more ways. It’s easy to get distracted. So we’d like to propose a simple way of focusing on metrics that gives you the ability to change while avoiding the back-and-forth whipsawing that can come from management-by-opinion. We call it the Three-Threes Model. It’s really the organisational implementation of the Problem-Solution Canvas we saw in Chapter 16.

The Three-Threes Model

At this stage, you probably have three tiers of management. There’s the board and founders, focused on strategic issues and major shifts, meeting monthly or quarterly. There’s the executive team, focused on tactics and oversight, meeting weekly. And there’s the rank-and-file, focused on execution, and meeting daily.

Don’t get us wrong: for many startups, the same people may be at all three of these meetings. It’s just that you’ll have very different mindsets as a board than you will as the person who’s writing code, stuffing boxes, or negotiating a sale.

We’ve also found that it’s hard to keep more than three things in your mind at once. But if you can limit what you’re working on to just three big things, then everyone in the company knows what they’re doing and why they’re doing it.

… and I realise that the three tiers of company execution apply just as well to individual careers as it does to company life.

- At the ‘board’ level, you want to be sure that you're on a path that makes strategic sense, given your longer-term goals. Activities like industry analysis (e.g. Grove’s framework for detecting strategic inflection points) shouldn’t be done too often; having it scheduled for each quarter is probably better than doing it as and when you remember to.

- At the ‘managerial’ level, you want to see progress on a small handful of goals for the week.

- And at the ‘execution’ level, you want to accomplish what you set out to do for the given day.

I think the key idea here is to avoid the natural tendency to jump between plausible directions. If you decide that you want to learn a new skill, it wouldn’t do to try it for a week or two and then jump away to another thing in the third week. Doing so is an incredibly inefficient approach to trial and error.

But it’s also a bad idea to keep your head down in pure ‘execution mode’. There’s an old productivity pearl about how ‘it doesn’t matter how fast you move if it’s in a worthless direction’ — and focusing on execution at the expense of analysis is a surefire way to guarantee that this happens.

Quarterly cycles make sense to me — they’re neither too short to mess with execution, nor too long to endanger one’s competitive positioning. They’re also a step up from GTD’s pure focus on task management.

I’ve created quarterly reminders for myself (along with short daily and weekly retrospectives), and I’m hopeful that this works as advertised. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Originally published , last updated .