This is a summary of a great 🌳 tree book on the basics of business. This book is rather unusual because it acts as a condensed guide on business for employees looking to advance in their careers. Regardless, because it is not a long book, I recommend that you buy it for reference. Read more about book classifications here.

Ram Charan’s What The CEO Wants You To Know contains a remarkably concise explanation of how a business works. It is incredible. It took me five years to truly grok some of these ideas; Charan takes all of that and squeezes it into a handful of chapters: a cool 100 pages in the paper edition.

Charan’s book also plays into one of my longest-held biases: he thinks that an understanding of business basics is necessary for a good career. In my case, I didn’t have much of a choice: my career was heavily-weighted towards startups from the beginning. This meant that I had to evaluate potential employers as actual businesses, not merely as places to find a job. I had to know if a company would be around in a year, or three; I could not coast on brand-name recognition the way my friends could with larger companies.

Charan goes further, however: he argues that employees of all companies should have an appreciation of how their business works. If they do so, he writes:

People feel more connected to their work and have greater job satisfaction when they really understand how their organisation works. And as the company grows profitably year after year there are greater opportunities for them to expand their careers and make more money, and the company can make a greater contribution to the community. (…) That’s why the best CEOs everywhere work so hard to explain things. And that’s why I want to share with you, in the words of the book’s title, what the CEO wants you to know, so that you can learn, grow, and make a greater contribution to not only your organisation but the world around you.

This sounds a tad wishy-washy, but there are tactical advantages to this. In the past, we’ve discussed how you can’t ignore business models in your career. Understanding the fundamentals of business is but an extension of that idea: if we assume that incentives drive organisational behaviour, then understanding business thinking is a surefire way to align your work with your company’s underlying incentives. It’s the sort of thing that should lead to better career outcomes over the long term.

The good news here is that there really isn’t much to grok. Charan explains that every business is the same inside, and that there are really only four principles that you must understand. These principles apply to fruit stands and noodle stalls; manufacturers and multinational service firms. They do not require special knowledge to learn.

This book summary focuses on these four principles. At under 200 pages, What Your CEO Wants You To Know isn’t a very long book; Charan spends the second part after the four principles on execution details — things like hiring well and creating process and putting the principles to practice. This second half is much weaker than the first half because Charan has limited space for nuance. We’re going to skip that entirely.

This is ok, I think: if you want to learn business, you’d understand that nothing you can read in a book beats actual experience. Charan’s guide is merely the skeleton on which you may organise your learning. It was written with the beginner in mind.

Every Business Is The Same Inside

In every business the basic building blocks are always the same. This can be boiled down into four parts:

- Satisfying customer needs better than the competition

- Generating cash

- Producing a sufficient return on invested capital

- Growing well

That’s it. There’s all there is. But Charan writes:

Most people know how to do one or two of those things really well. True businesspeople understand all four parts individually as well as the relationships between them. Businesspeople have an insatiable desire to cut through to the fundamental building blocks of moneymaking.

It’s that last part that’s key.

Everything about a business flows from a nucleus of customers, cash generation, return on invested capital, and growth. This includes the little things that you — in your capacity as an individual employee — care about, like promotions and hiring, product development and inventory management, employee compensation and marketing spend. If the four-part core is unhealthy, the company will eventually falter. Layoffs occur. Department budgets get cut. If your grasp of the four-part core is strong, you can usually tell how you’re going to be affected before that happens.

The four-part core can be translated into a series of questions:

- Is the business attracting and retaining customers?

- Does the business generate cash? (Note how this question isn’t ‘is the business profitable?’; we’ll get into this in a bit)

- Is the business earning a good return on the money invested in the business?

- Is the business growing? And if it is growing, is this good growth or bad growth?

Keep these questions in mind as you read this summary. Ask yourself how they apply to the business you work in. And then work out the second order implications on your career from those answers.

Principle 1: Customers

There’s a Peter Drucker maxim that goes “the purpose of a business is to create a customer.” This is true: without a customer paying you, you have no business. So the first component of moneymaking is simply providing a service or offering a product that a customer will pay for.

Much of the startup literature is focused around this aspect of business. We have Eric Reis’s The Lean Startup, Clayton Christensen’s Competing Against Luck, Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing The Chasm and Steve Blank’s The Four Steps to the Epiphany, all books that focus on the challenges of developing a product and bringing it to market.

The core idea, however, is simple: is your business able to attract customers against its competition? Why or why not? In order to understand this, you must understand why your customers are buying what you offer. It may not be the physical product alone. They could be buying reliability, trustworthiness, convenience, or the customer experience. (This is sometimes known as the ‘job to be done’ framework for understanding business.)

An added wrinkle is that some businesses serve customers who are not consumers of their products. An example is P&G — which develops products for the household ‘consumer’ — but serves stores like Walmart and Target, who are their ‘customers’. Many processes in P&G’s business (such as logistics, discounts and merchandising) are thus geared towards retail stores instead of the end consumer.

This wrinkle doesn’t change the basic principle, however: good businesspeople know why their customers are buying their products and services. They know what levers go into their customers’s purchasing decision. A fruit vendor looks at what his customers buy on a daily basis, and develops a feel for what fruits are popular and what are not. A multinational CEO (that Charan particularly admires) visits retail outlets to talk to customers, taking care to observe where they come from, what they buy, and where they go to after visiting the store.

Good businesspeople do this because many things stem from the customer. When they can’t get the prices and margins they used to, they know to talk to the customer to find out why.

This is easy to say but difficult to do. Here’s a personal story to illustrate this difficulty: I do content marketing work for a friend’s SaaS company, on the side. The first step in marketing is understanding why the customer purchases from your company. Once you understand that, you know how to go after prospective customers. What I’ve learnt from my experience with this company is just how difficult it is to understand why a customer purchases you over your competition. It’s easy to say “oh, just go talk to customers!”, but incredibly hard to synthesise the qualitative experience of doing so; like art, you can only know if you’ve tried.

Principle 2: Cash Generation

Cash generation is the difference between all the cash that flows into the business and all the cash that flows out of a business in a given time period. Conventional business jargon calls it ‘cash flow’, but Charan prefers ‘cash generation’. He says the latter phrase forces everyone to understand both parts of the concept: the money that flows in, and the money that flows out. I don’t really care about Charan’s distinction between the two names, but the idea is subtle and simple and important to grasp.

Cash flows into a business in the form of cash, checks and credit cards for the sale of its products or services. Cash flows out for things such as salaries, taxes and payments to suppliers. So far so good. But a company with good cash generation is different from a company that is profitable. This nuance matters.

When you are a street vendor, you pay your suppliers in cash and you receive cash from your customers. In other words, your cash flow and your income are one and the same. Larger companies, however, may have customers who buy now but pay later (accounts receivable), and may themselves purchase product from suppliers now but pay later (accounts payable). In other words, companies may make a sale today and book it as income, but the real cash only arrives in their bank accounts a period of time after. The timing of these payments affects cash generation.

Businessperson Tren Griffin likes to quote Wu-Tang Clan’s ‘C.R.E.A.M’, or ‘Cash Rules Everything Around Me.’ He repeats it as a mantra because companies can forget that cash is ultimately what matters in business. You can’t pay salaries or taxes with accounting profit, after all. It has to be cash — or, as Method Man puts it, “CREAM get the money, dollar dollar bill, y'all.”

It seems odd that cash generation matters more than profit. But at some level this makes intuitive sense: unprofitable startups can keep going for as long as they have money in the bank; profitable companies get into trouble when they don’t have enough cash and are unable to borrow. When that second scenario happens — think General Motors in the 2008 crisis — they go bankrupt.

(Conversely, companies can delay turning a profit if they have good cash generation. An exercise for the reader: how is it possible to run a company at an accounting loss with positive cash flow? What does this mean in terms of a business playbook?)

I think one of the more striking cash flow examples in the book is that of a management consultancy that was running out of money. The senior partners had borrowed heavily to buy the company, which meant a lot of cash every month to make the interest payments. At one point, it was clear that they were going to run dry, and the only option seemed to be to sell off a piece of the business, which would diminish each partner’s ownership stake.

Right before the deal was signed, however, the CEO had an insight that saved the partners’ share of the business. She realised that clients were paying on a 90-day payment term, instead of the 45-day industry average. This payment term meant that it took 90 days on average from the time the firm sent an invoice to a client until the time it received the money.

So what did the CEO do? She changed the payment terms. She also got partners to send invoices as projects progressed, instead of waiting for the end of every month. These simple tweaks changed the cash situation of the business and allowed it to keep running. Charan writes:

Cash gives you the ability to stay in business. It is a company’s oxygen supply. Lack of cash, a decrease in cash, or increased consumption of cash spells trouble, even if the other elements of moneymaking — such as profit margin and growth — look good.

What Does Cash Generation Have To Do With You?

Charan takes pains to explain that everyone can contribute to their company’s cash situation. It is easy to think that only the finance department is responsible for healthy cash flow, and you do whatever it is you were hired to do. But nearly every activity in a company either uses cash or generates cash, which means that simple tweaks to your work can lead to different outcomes for the company’s cash generation:

- A sales rep who negotiates a 30-day payment term instead of a 45-day payment term is cash-wise. The company can get the money sooner and is able to put it to use elsewhere.

- A factory manager whose poor scheduling results in excess inventory consumes cash, because the company won’t be able to free up that cash until the inventory is sold to customers.

- Even something as small as cashing checks matter: if you process your mail in the afternoon instead of in the morning, you may cause a two day delay on Fridays if the checks don’t get cashed in time for the weekend. This is two extra days where the cash isn’t in the company’s coffers.

It’s probably an interesting exercise to ask yourself these questions:

- Is your company a net cash generator? Why, or why not?

- If your company isn’t a net cash generator, is it because management is investing in growth, or you have too much tied in inventory, or expenses are too high, or payment terms are too long, or your company has borrowed too much and is struggling with payments?

- Does your division generate cash? Why, or why not?

- A division may occasionally be ‘managed for cash, not growth’ — meaning that the cash from the division is being used to fund other parts of the company. This could be another department that’s growing rapidly, or it could be R&D for a new line of business. Whichever it is, you should know, because it affects the incentives that govern your boss’s decisions.

Understanding Gross Margin

A key part of understanding cash generation is understanding gross margins. The idea behind gross margin is simple: it is the amount of money you make minus the costs directly associated with making or buying it. These are things such as the cost of material used to create the products (cost of goods sold, or COGS), along with the direct labour costs. It doesn’t include indirect costs associated with making the product — like cost of sales and general administration or distribution costs.

Gross margin is different from net profit margin — which is the amount the business makes after paying off all its expenses (this includes COGS, but also fixed costs like rent and interest payments and taxes).

The formula for calculating gross margin is easy: you take the total amount of revenue your business makes, subtract COGS from it, and then divide by revenue.

Gross margin can be expressed as a total number, or as a percentage. Let’s say that you’re like Ram Charan, and you grew up with a family business — a shoe store — in India. If you sell 1000 pairs of shoes at $50 a pair, your total sales is $50,000. You bought those shoes from your supplier for $30 a pair, meaning COGS is $30,000. Your gross margin is thus $50,000 - $30,000 = $20,000, or 40%.

Why is gross margin so important? As with most things in this book, the number itself isn’t as important as the factors behind it. Your business’s gross margin may be manipulated using a number of levers:

- The product mix — perhaps some of your products have higher margins than other products. Changing the mix changes the overall gross margin of your company.

- The customer mix — perhaps some segment of your customers are less profitable compared to others. (For instance, you make a software product and have students as part of your user base). Cutting those out might change your overall gross margins.

- The cost structure — is it getting more expensive to produce your product? Why? What can you do differently if this is the case?

A good businessperson has an intuitive grasp of the factors that affect her business’s gross margins. This in turn has an effect on the cash generation of her business. All else being equal, declining gross margins usually mean a future with worse cash generation. If the businessperson doesn’t watch the commensurate cash outflows, things can get very difficult very quickly.

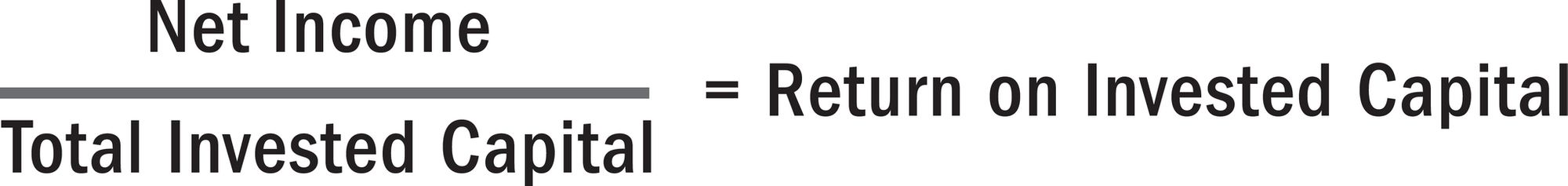

Principle 3: Return on Invested Capital

Gross margins lead us to the third principle in Ram Charan’s four-part nucleus. A business is a machine that takes in money on one end and turns it into more money on the other. The return that money makes is known as the return on invested capital.

The formula for ROIC is (again) easy: you take your net income and divide it by your business’s total capital (your money plus any money you have borrowed).

The higher your ROIC, the better. Again, the formula for this metric isn’t as important as the idea behind it: imagine that your business is a slot machine. You put one dollar in on one end of the machine, and the machine spits out a certain amount of money — say, three dollars. Your ROIC is the multiple the machine gives you — in this case, you have a multiple of three.

When it comes to gauging the health of a business, your ROIC calculation doesn’t need to be precise. What you really want to get at is a sense of the measure over time. Is your slot machine’s ROIC number better than last year, or the year before that? Is it better than your competitors’s? Is it where it should be? And where is it headed?

Charan points out that for street vendors, ROIC is an intuitive concept. You either grasp it or you languish. Years ago, Charan brought a group of MBA students to an open-air market in Nicaragua. They approached a woman selling clothing in a small shop, and asked her how she got the money to pay for her merchandise. This is what happened next:

She said she borrowed it, paying 2.5 percent interest a month. One fast-thinking student did the math—2.5 percent multiplied by twelve months—and announced that the interest rate was a whopping 30 percent a year. The woman gave me a disapproving look and said in Spanish that the student was wrong. Compounded month to month, the rate was actually 34 percent annually.

How much margin did she make? Just 10 percent. So how could she survive borrowing money from loan sharks charging 34 percent a year? We had to ask.

Annoyed by the stupidity of the question, she made several sweeping circular motions through the air. Her gesture meant rotation—rotation of inventory, or turning the stock over. She knew intuitively that earning a good return had two ingredients—profit margin and velocity. If she sold a blouse for $10, she made just $1 in profit. To pay the interest on the loan and to restock her cart, she had to sell her wares again and again during the day. The more she sold, the more “10 percents” she accumulated.

‘Velocity’ is the term used to describe the idea of speed, turnover, and movement. Imagine raw materials entering into a factory and turning into finished products, then those finished products moving into stores, and then flying off shelves to be used by the end consumer. How quickly does this occur? That is velocity.

Velocity may be calculated by taking your total sales for some product for, say, a year, divided by the value of that product. If you want to look at inventory velocity, divide total sales by total inventory. The number you end up with is often called ‘inventory turn’ — as in, “how many times does your inventory turn over in a year?” Walmart, for instance, has 360 inventory turns in toilet paper a year. That means the entire inventory of toilet paper is sold out almost every day — allowing Walmart to recoup their cash along with some profit each time that occurs. For Walmart, toilet paper is a great use of shelf space and cash. (Exercise for the reader: how would Walmart’s cash generation be affected if it expands its product offering to include more toilet paper?)

Again, Charan stresses that the formula isn’t as important as the concept of velocity itself. Ask yourself: in your company, how long does it take from the time an order comes in to the time it is delivered to the customer? And if your business holds inventory (like my old company did): how long is it before you have to resupply?

The reason velocity matters is because it contributes directly to the return you make in the business. This is expressed with a formula that represents a ‘universal truth in business’: basically, that your return is simply your profit margin multiplied by velocity. This is expressed like so:

Return (R, expressed as %) = Margin (M) × Velocity (V)

Charan points out that many people focus on profit margins alone. The best businesspeople — the ones ‘who will be promoted’ — focus on velocity as well. He continues:

Velocity is important to every company. Consider companies that have a lot of “fixed” assets—factories, machinery, or buildings. Take, for example, AT&T. It has a huge investment in wires, cables, satellites, and microwave towers. With prices for long-distance voice calls falling due to decreased demand (know any college student with a landline in her dorm room?) and margins shrinking in its cellular business (thanks in large part to the intense competition), the only way to improve the return on its invested capital is to focus on velocity.

How? By offering cell service, Internet, and television through its network.

A particularly fun exercise is to look at how velocity is expressed in other types of businesses. Take a recent episode of Planet Money titled The Trouble With Table 101. The episode examines the nature of the restaurant business in New York — specifically, the relationship between average check size for a table and the amount of time people spend at said table. The shorter the amount of time, the more people pass through the restaurant — and the more orders the restaurant can serve (velocity). Conversely, the larger the check size, the higher the profit margin. But here’s the rub: you need a balance between the two. Too little time at a table results in decreased check size (and therefore profits); too long and you have low velocity. The rest of the episode examines the levers that go into this balancing decision, as experienced through the eyes of one extremely popular restaurant in New York.

Velocity and margin are particularly important to a business, because they are the two levers that most directly influence a company’s returns. Charan underscores this importance by explaining that merely earning a return is not enough. In truth, returns must clear the ‘cost of capital’, or bad things will happen in the business.

The cost of capital is the cost of using your own or other peoples’s (banks’s and shareholders’s) money. This cost is usually dependent on the prevailing interest rate — and there are many ways to calculate it which I won’t get into. The important idea here, however, is that if ROIC fails to exceed the cost of capital, there will be real upset amongst investors in the company, because it means that management is destroying shareholder wealth. (Why should they invest money into your business if they can make more by putting it into a Treasury bond?)

All companies will eventually have to do something about businesses, divisions, or product lines they own that do not earn above the cost of invested capital. They will either have to sell off (divest) the business or discontinue the product line. Charan closes off this section with the following piece:

You can help make a difference by suggesting ways to improve the return. If, for example, you work for an automobile company, you’ll find the return on small cars is problematic. Auto manufacturers around the world have been earning less than a 2 percent return on them, which is less than the cost of capital. How might that part of the business generate a higher return? Or if you work at a software company, think once again about the formula for return on invested capital, where ROIC = net income divided by total invested capital. Because (in a software company) the denominator is so small, any way you can figure out to boost net income can have a big effect.

Principle 4: Good Growth

ROIC brings us to the next and final principle in the nucleus of business: growth.

Charan makes a rather controversial assertion in the introduction to this section: if your company isn’t growing, then it is dying. The argument goes something like this: in a world that grows every day, a company that is standing still or doing ‘just fine’ is falling behind. A company that is overtaken by a competitor eventually gets boxed in. It loses many of its advantages over time. Charan’s conclusion: growth is imperative to business.

This assertion isn’t true for all industries, nor is it true at every company size. SMEs, for instance, seem to get along just fine at a certain size, even if they are constrained by factors outside their control.

But Charan also makes a more pragmatic, less controversial argument: the growth of a company enables one’s career growth. This is common sense:

If the company is not growing profitably or your business unit lags behind competitors, your personal progress will suffer. You will not have the opportunity to be promoted and move forward. Top managers will begin to cut costs and reduce the number of employees. They’ll start reining in R&D and advertising. Good people will leave, and eventually the company will go into a death spiral and employees—including you—will suffer.

On the flip side, however, some companies grow themselves to death. Charan gives us three stories to illustrate this fact, but any reasonably curious observer of business would have noticed similar stories. Here’s story one, a common tale of using leverage to fund growth:

Many entrepreneurs taste success on a small scale and become obsessed with growth, losing sight of the moneymaking basics along the way. Unfortunately, the case of one entrepreneur who served restaurants is typical. He built a profitable business installing beverage equipment at a cost of $2,000 per installation and thereafter collecting $100 a month from the restaurant for the ingredients he supplied.

So far so good. But he borrowed money to make the installations, and the margin on the ingredients was so slim that it did not cover the interest payments. Yet he was obsessed with growth and kept installing his equipment in more and more restaurants. The outflow of cash soon outpaced the flow of money into the business, and the lenders decided that the company needed a new CEO.

Story two, which is a story about bad sales incentives:

Sometimes senior management inadvertently encourages unprofitable growth by giving the sales force the wrong incentives. For example, one $16 million injection moulding company rewarded its sales reps based on how many dollars’ worth of plastic caps they sold; they were not accountable for profits. Everyone was excited when the company landed $4 million of new sales from two major customers, but these large contracts were on slim margins, not enough to generate the cash needed to fund the sales.

And story three, on the perils of triggering a price war:

To rev up its business in an important unit, a global building company brought in a new division head. He was the heir apparent to the CEO of the parent company and his new assignment was a major test to see if he was ready for the top job.

The new manager believed he could gain significant market share by cutting prices. He was successful—at first. Sales grew over the next three months, and so did the unit’s share of the market.

However, the competition responded in kind. Desperate to preserve their market shares to cover their high fixed costs, competitors also cut their prices. The end result? All the price cutting caused revenues, profits, and cash generation to shrink throughout the industry, hurting Global Building along with everyone else.

Those of you who are ardent students of business would have probably come across similar stories. These aren’t unusual by any means. Good businesses die all the time in the pursuit of bad growth. There is something about the shininess of growth itself that cause many businesspeople to forget the simple principles of this section.

So what, then, is good growth? Charan proposes that good growth is profitable, organic, differentiated, and sustainable:

- Profitable. Good growth not only generates profits but is also capital efficient. It needs to earn an amount greater than the company would receive by investing its money into something ultra-safe like a Treasury bill.

- Organic. Good growth nearly always flows out of the company’s existing capabilities. A corollary: a company’s job is to systematically expand its set of capabilities.

- Differentiated. Charan writes “you never want to provide a product or service that is seen as a commodity. Customers must prefer it. Otherwise, you will never make very much money”. A more nuanced take on this is that the growth must be defensible — and a differentiated product offering is merely one defensible strategy. There are others.

- Sustainable. Growth should continue year after year, instead of providing a quick spike in revenue. Growth that triggers a price war is by definition not sustainable.

In the end, the ultimate measure of growth are the metrics that we’ve covered earlier — cash generation, in particular. Remember Tren Griffin’s mantra: ‘cash rules everything around me’. If sales is growing but cash isn’t, take a step back to figure out why. Are profit margins shrinking? If you sell to other businesses, are your current payment terms too loose? Has your customer mix changed, changing your product mix and your gross margins along with them?

Often, businesses must spend money and take a temporary hit in cash generation in order to grow. Manufacturing companies come to mind: they must pay for raw materials and — if expanding — cough out money to build out additional factory capacity. But subscription-based business models also suffer from similar dynamics. In subscription-based businesses, a company spends a certain amount of money to acquire a new customer. That customer then pays a small amount of money each month for the product or service. If it costs $500 to acquire a customer and the customer pays $100 a month, then it will take five months to recoup the cost of acquiring that customer. This is know as the payback period. SaaS companies that are growing will thus suffer from what is known as the ‘SaaS cash trough’: that is, they will have a severe cash problem until all the new companies they’ve just acquired hit their payback period.

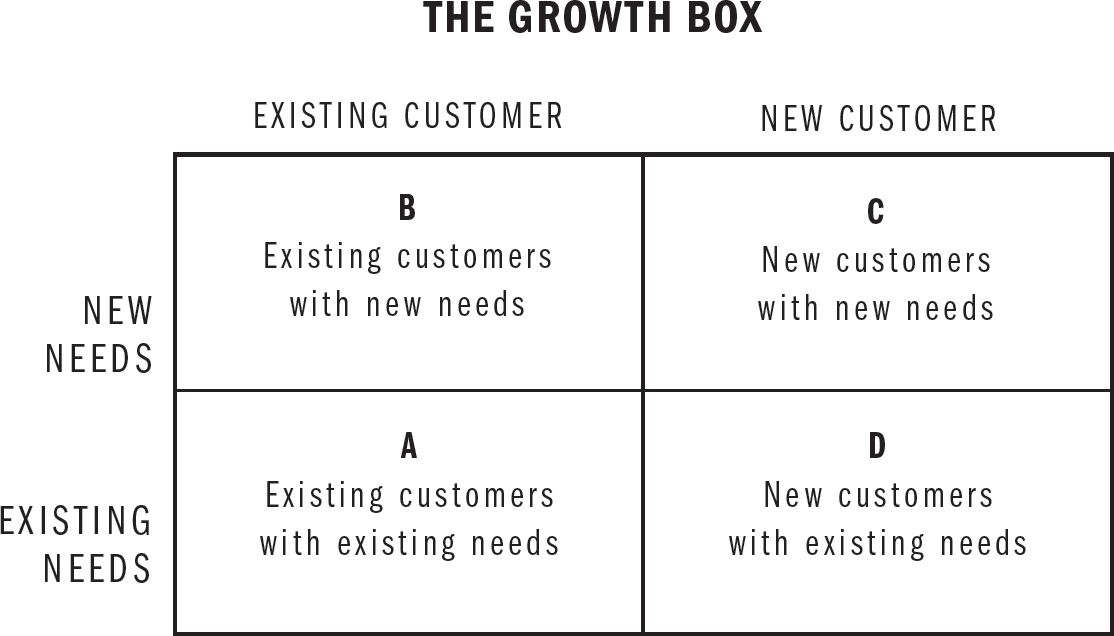

Understanding the properties of good growth is often what is simple. The more difficult bit is in finding opportunities for good growth. Charan gives us the typical business school growth box:

He then suggests that thinking about the four quadrants can trigger ideas for growth. But make no mistake: pursuing growth is an art. It’s one of those things that come from practice and observation, not from the avid study of frameworks. Charan can help explain what good growth looks like, and warn you against the dangers of growth for growth’s sake, but the practice of finding and executing on growth opportunities falls squarely on the shoulders of the business practitioner.

Conclusion

So let’s wrap up. What The CEO Wants You To Know is a fantastic book — short, to the point, and with a great formulation of the basic principles of business.

My central thesis with this summary is that even a rudimentary understanding of business basics helps you in your career — regardless of what industry you’re in, what level you’re operating at, and the specific role you play in your company. Charan spends most of the book tying these principles back to the individual employee, helpfully providing questions and examples that span the business world. But I think these implications should be worked out according to your own situation. Ask yourself:

- Why does your business’s customers buy from your company? Why aren’t they buying from other competitors? More importantly, does your company know these reasons? If they do not, can you find out?

- What is the cash generation situation of your company? A company that is profitable might not have good cash flow; conversely, a company that isn’t profitable today may have good cash generation — or at least, good cash generation down the road. The question you should be asking is if management understands the nuances of cash generation, and thinks about it like a businessperson does. This usually takes the form of two parts: first, understand the incoming cash flows and outgoing cash flows of your company. Second, analyse the actions that your company takes. Are its actions consistent with the cash situation you’ve uncovered in the first part? This tells you something about management’s understanding of cash generation. (This is especially important if you’re working at a startup, where management can be as clueless as a bull in a china shop.)

- Is the ROIC of your company going up? More importantly, does management understand the concept of ROIC? If so, what are they doing about it?

- Is your division or company managed for cash or growth? If it’s being managed for growth, is that growth profitable, organic, defensible, and sustainable? Often, these analyses can be determined from hard metrics. Other times, they demand subjective judgment. If they demand subjective judgment, how do you know that your judgment is correct?

I like Charan’s four-part nucleus because it is simple and easy to remember. It helped me organise my experiences in a coherent manner. Depending on where you are in your exposure to business, it might take you a bit of time to integrate into your own experiences. But ultimately, I think you'll find that it isn't very complicated.

Consider this book my first book recommendation of 2020. It’s great.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Capital topic cluster, which belongs to the Business Expertise Triad. Read more from this topic here→