Some minor housekeeping.

In Commonplace's About Page, I explained that this blog is about my journey to build career moats. In so doing, I wrote that I would follow the following three principles:

- My primary recipe here is 'take interesting idea that seems to be useful, try it out in my career, and then write up the results'.

- I will bend this writing towards usefulness.

- While bending towards the practical is good, I promise to mix things up.

After nearly a year of writing, I've come to realise that principle #3 isn't particularly useful, nor true. I've not veered much from writing about techniques that are practically useful; even the more speculative stuff that I write about eventually gets turned into a test of some kind.

These principles are something that I actively think about when publishing on Commonplace. Given that I've not done a good job of embodying the third principle this past year, I've decided to change it.

Starting today, I'm going to adhere to a new principle (I've included the old one at the end of this post, for posterity):

3. I will write with the appropriate level of epistemic humility, and I will cite with an appropriate level of epistemic rigour. On humility: I will use more confident language if I am writing about topics within my circle of competence, and less if I'm not. I will be upfront as to which it is. On rigour: when I cite scientific studies, I will keep in mind the weaknesses of null hypothesis statistical testing. I will perform checks — limited by time and my statistical sophistication — to verify that results are not rubbish. When citing practitioners, I would vet their recommendations according to my hierarchy of practical evidence. This is because you deserve to know if the techniques I write about are rubbish.

Here's a slightly longer explanation.

If you're trying to improve your life (in this case, building career moats), you are looking for techniques that work. How do you evaluate this? Well, it usually boils down to:

- A technique that is backed by scientific evidence. Think: the spaced repetition effect. You get this by reading the academic literature.

- A technique that is backed by expert experience. Think: ‘reasoning from first principles’. You get this when an expert shares some of their techniques.

Before you put these ideas to practice in your life, you should have some way to check their validity. Not everything is worthy of your time. Single studies with poor statistical power should be regarded with suspicion. A time management technique by Joe Random Schmuck on Medium (whose only accomplishment in life is writing on Medium) should be treated as clickbait.

These two types of evidence must be evaluated according to two different metrics. For science:

- Do not believe in the results of any single study. Scientific results are only true in the context of multiple, repeated studies. Such information is usually found in meta-analyses or summary papers.

- Read meta-analyses and summary papers where possible. If none exist, understand that you will need to read a significant portion of the papers in the subfield to have an informed opinion. It you don't have the time, it might be better to profess ignorance!

- Statistical significance is irrelevant without statistical power. Understand the flaws of null hypothesis statistical testing.

- When possible, discount popular science books in favour of academic textbooks. Book publishers do not have fact-checking requirements for non-fiction books, and popsci books are often written by journalists with a lack of statistical sophistication. This stands in contrast to academic textbooks, which are written for other academics to use in their teaching. This puts the author's reputation on the line.

- Distrust blog articles, news articles, and twitter threads that do not link to source material. Do not take reported results at face value! The original papers often say something subtler than what is reported in popular media.

- Do not hold to scientific standards that which isn't science. Anthropological papers, medical case studies, and philosophy isn't science, so aren't subjected to the standards of falsification. This does not make them useless.

- Understand that statistical predictors do not predict things at an individual level. (More here).

On evaluating anecdotal evidence from practitioners:

- When getting advice on swimming, you will value advice from a competitive swimmer more than you would from a friend who doesn't know how to swim. Similarly, you should evaluate advice by the credibility of the person giving it.

- Understand that even if you take advice from a believable person, the technique that the person explains to you is not guaranteed to work for you. There are all sorts of confounding variables to explain the person's success: luck, privilege, genetics, and environmental differences. This shouldn't dissuade you from attempting to apply their techniques, but you should be prepared for the technique to fail, and you should also be prepared to do some experimentation in order to adapt it to your unique circumstances. (More here).

- Because of confounding variables, the highest standard for truth in anecdotal evidence is if you have tested the technique in your own life, and have found that it works for you (but you shouldn't believe it would work for someone else!)

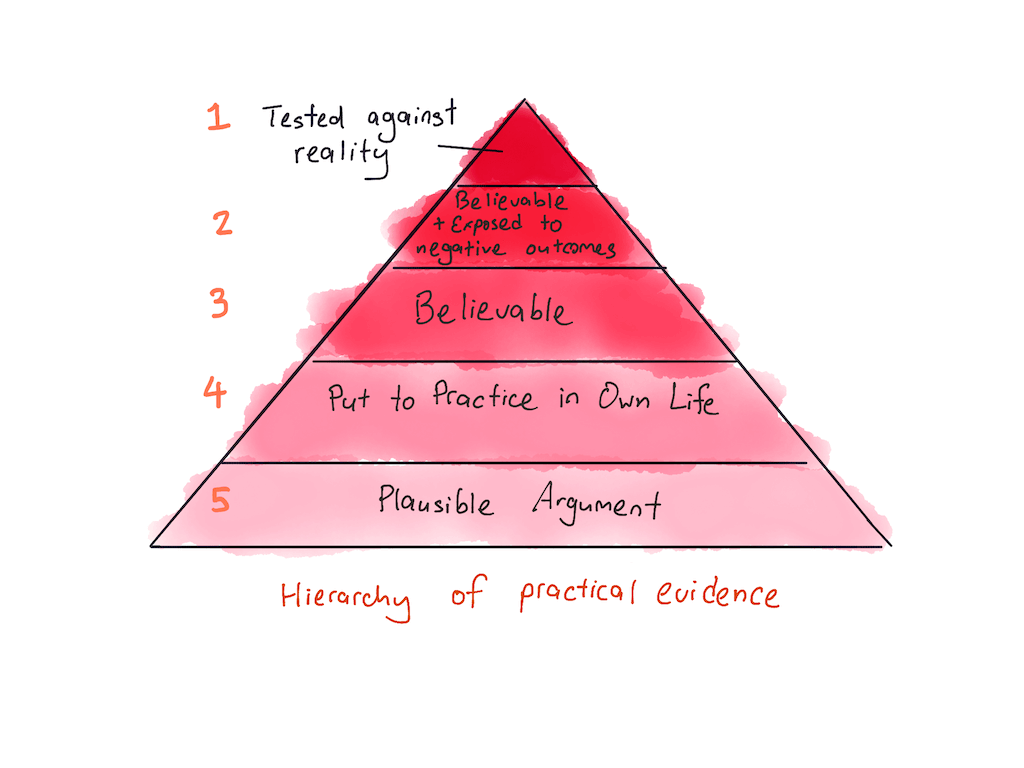

- Under this is a hierarchy of practical evidence: at the top, but below ‘tested in your own life’ is advice from experts who are believable (definition) and are exposed to negative outcomes in their field. Below them are experts who are just believable, but do not have skin in the game. Below them are practitioners who have put the technique to practice in their own lives. And below that, the lowest level worthy of consideration, is a plausible argument for the technique. See a visualisation of this hierarchy below.

- Don't spend time arguing about putting the technique to practice. Don't complain about that person's luck, genetics, privileges, or external circumstances. This is because it is not useful to you. Time spent winning arguments about technique is time not spent experimenting with those techniques in service of winning.

This is the epistemic stance that Commonplace will take. I will strive to write everything in this spirit.

For scientific evidence, I will do my best to verify the source material. For practical techniques, I will attempt to put things to practice in my own life.

Consider this my skin in the game.

Errata

Definitions:

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that asks “how do we know that something is true?”

Epistemic humility is the stance that we cannot truly know the truth, but we can inch ever closer to it. While doing so, we should recognise that there is a gap between our knowledge of the world, and how the world truly works.

Epistemic rigour is the level of rigour that we use when we approach statements of truth.

The old principle, as promised:

3. While bending towards the practical is good, I promise to mix things up. Not everything has to be serious, and not everything has to be practically useful. One cannot predict the future based on a narrow field of ideas. I'll spend a small percentage — perhaps around 20% — on less immediately useful stuff, in the hopes of hitting something important.

Originally published , last updated .