Note: this is the first part of a series of posts that summarises what I’ve learnt about improving my decision making and thinking. It builds on many of the ideas that we’ve covered on Commonplace, and is motivated by the observation that ‘mental models’ are only valuable to the extent that they are practicable.

This series provides a constructive alternative to the criticism I made in The Mental Model Fallacy, which took Farnam Street as its primary target. Shane Parrish of Farnam Street reached out to me over my criticism and invited me to join his private discussion group; this series of posts was thus originally written and published in the Farnam Street Learning Community.

The Problem

There’s a famous speech delivered by Charlie Munger at the USC's Business School in 1994, titled Elementary Worldly Wisdom. In it, Munger argues that you should learn lots of mental models from a large selection of disciplines, and then use that to provide context and colour to your decision making processes. This practice, Munger asserts, leads to wisdom; it is how he became so successful at investing and at life.

In the years since Munger’s original speech, there has been an uptick in self-help books and blogs focused around exactly this effort. The idea goes that if you summarise a large selection of mental models from a wide variety of fields, you would be able to use this list to ‘improve’ your thinking. The most popular amongst these blogs is Shane Parrish’s Farnam Street, who was the first person to notice this method, and the first to begin writing widely about it.

I have one problem with this approach, though. I think Munger’s prescription isn’t rigorously actionable. Or, to put this another way: I've put it into practice, and it doesn’t seem to make me better.

I suspect that I’m not alone in this. In Farnam Street’s Learning Community alone, I’ve seen threads by multiple people asking how they should put mental models to practice. So far, the answers I’ve read haven’t been very satisfactory.

I don’t mean that in a disrespectful way. When I first read Munger’s speech five years ago, I thought it was a remarkable approach written by one of the best investors in the world, and so I thought I should find a way to learn this new approach he’d talked about.

But then adopting Munger’s prescription to read widely and pick elementary findings from Physics, Chemistry, Biology and Psychology didn’t cause me to get substantially better in pursuit of my chosen goals. (My Computer Science degree had a requirement for us to take a handful of basic science classes — freshman level Chemistry, Physics, or Biology, all of which we hated — so it wasn’t like I had to go out of my way to acquire models from those domains. I merely needed to do more reading in Psychology).

It is usually at this point that someone pipes in to say that “mental models are ways of looking at the world. I don’t think you can really practice them.” I reject this claim as strongly as the ocean rejects oil from a capsized tanker. If you’re reading this, it’s highly likely that you think mental models are a method to self improvement. You spend time reading about mental models in order to be more effective at your decision-making and at your life.

With that goal in mind, imagine that you are now a professional basketball coach, and you find yourself with an NBA player who says “Oh, I think technique is just a way of seeing the world. I don’t think you can really practice it.” What would you do?

You’d fire him, that’s what.

I believe that you need practice to truly know something, the same way that reading a math tool in a textbook and applying it to solve a math problem are two different levels of knowing. Similarly, claiming that “mental models are ways of seeing the world to find how the world truly works” is a bizarre claim if you don’t have the feedback loop of practice. How can you know if your mental models are right if you don’t test them rigorously?

So I think there are two interpretations to what’s going on here. I’m not yet sure which is the right one.

The first is that perhaps Munger wasn’t speaking to me. He wasn’t speaking to beginner or intermediate practitioners. He was assuming that the people he was giving his worldly wisdom speech to (USC Business School, if you recall) were going to become master practitioners through the usual skill-stacking means, and once they became good at what they did, he believed that ‘having a diverse latticework of mental models’ would give them the edge that makes him so rare in the business world. To put this another way, I don’t believe Munger was recommending ‘Elementary Worldly Wisdom’ as a path to mastery. I think he was recommending it in addition to the normal ways humans achieve mastery.

The second interpretation is that perhaps Munger’s recommendations lends itself more strongly to investing and finance. It makes sense to me that investors have to use many models as they go about doing their work; Munger himself goes into detail of ‘the art of stock picking as a subset of elementary worldly wisdom’ in his original speech. In order to pick good investments, you’re likely to need a large selection of models to make sense of diverse businesses in different markets, the economic fundamentals governing their external environment, management principles to evaluate their leadership, consumer psychology, and so on. See this Scott Page article on this argument, for instance.

Investors have an additional advantage over the rest of us: their field offers good feedback loops because performance is well-defined. Given time, you know if you’ve picked the right stocks because it’s relatively easy to measure performance (compared to other messier fields like management, or teaching, or computer programming). This is not correct, as I discover in Part 4.

The fact that Farnam Street has a wide readership in finance seems to bear this out.

So where does this leave us? Let’s consider the implications of the above interpretations.

If you are an investor or finance wonk, you’re likely to benefit from the Farnam Street approach — read widely for mental models, grow your bag of ‘lenses’ for evaluating investment opportunities. The nature of your work will allow you to check if your models are correct because finance affords you tight feedback loops.

But if you aren’t in finance, as I am, then you’ll need an alternative approach.

My background is in software development and management. My goal is to build a business of my own. I know that there are many of us are not investors — those who are interested in mental models and self improvement include teachers, writers, designers, data scientists, and more.

This framework is for this second group.

Quick Digression: Epistemological Setup

I’ll write a separate, longer post on this topic later on in this series, but we need to spend a little time talking about epistemological evaluation in our framework.

‘Epistemological evaluation’ is simply a fancy way of saying ‘how do you know this is true?’ The reason we need to talk about this is because I’m going to be making a bunch of assertions in the coming paragraphs (in fact, I’ve already made a bunch of assertions above) — and we need to agree on a basis of evaluation. To put this another way, in order to be rigorous, we need to have a framework for evaluating truth in the context of practice.

In science, what is ‘true’ was worked out by a bunch of philosophers in a branch of knowledge we call philosophy of science . There are well-known methods of evaluating scientific claims: you understand that truth is always conditional, that you may only disprove something, never truly ‘prove’ it. For contemporary science, you know to ask questions like “what is the statistical power of the study?”, “is there a meta-analysis on this topic” and failing that, “Is there a double blind study on this topic?” and you are careful to avoid trusting single small-sized studies because of the dangers of p-hacking. (For a longer, more rigorous treatment of the problems with null hypothesis statistical testing, I refer you to gwern’s excellent summary over at LessWrong).

But there are alternative forms of knowledge. For instance, when you want to learn to defend yourself, you go to a martial arts sensei, not a martial arts scientist. Nicholas Nassem Taleb refers to this kind of knowledge, for instance, when he says that if you want to create a better hummus, you should turn to cooks, not food scientists. The Ancient Greeks call this knowledge ‘techne’, or art. I’ll call it ‘practice’.

The reason we must be clear of the differences is because smart people conflate scientific standards for knowledge with practical standards for knowledge all the time. See, for instance, this example of economist Robin Hanson holding Ray Dalio’s Principles up to the standards of science. He finds it badly-written and wanting. But a practitioner can mine Dalio’s Principles for actionable techniques and apply it to their own lives to great effect.

I can and will write a much longer treatment on this topic, but for now, I want to focus on two principles.

The first — and probably the single most important — principle is to ‘let reality be the teacher’. That is — if you have some expectations of a technique and try it out, and then it doesn’t work — either the technique is bad, or the technique is not suitable to your specific context, or your implementation of the technique is bad, or your expectations are wrong.

However, for the purposes of practice, reality is a higher resolution teacher than words on a page, or instructions from a practitioner. If it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. Maybe you’re not ready for it yet. Maybe it doesn’t work for your unique personality, or your unique situation. Go try something else.

The implication here is that you shouldn’t rubbish techniques and suggestions documented by other practitioners — provided it has been shown to work for them. If, for example, a technique that a practitioner like Andy Grove uses at Intel cannot possibly work in your organisation, there is still value at examining why the technique works in his, and then attempting to adapt that principle to the unique context of your life.

The second principle flows from the first. When it comes to practice, one should pay attention to actual practitioners. This is because their approaches have been tested by reality.

This principle is formalised in Ray Dalio’s book as the Believability metric. It makes sense because you do need a filter for advice, which for Dalio means paying more attention to people who are believable in their chosen domains. This means that you should judge them according to what they’ve actually accomplished, keeping in mind that what works for them might not work for you because of hidden differences in their person or in their situation.

A second order implication means that if you tell me something you have actually done — I will pay close attention! And I will do so even if you have not accomplished as much as Dalio’s believability metric demands (i.e. at least three successes in your field + a credible explanation for your approach). This is because you have put it to the test in your life, which means you have let reality be your teacher.

A more concrete example suffices. There are many self-help blog posts about deliberate practice, but a quick way to filter for usefulness is to scan the article for hints that the writer has actually tried putting deliberate practice into … well, practice. If they haven’t, then you should ignore them. If they have, then read carefully.

It is really, really difficult to create a deliberate practice program for an unstructured skill — even Anders Ericsson himself admits that he does not know how to deploy deliberate practice for skills like solving crossword puzzles and folk dancing. The self-help hacks who have never actually tried putting this into practice will not mention that it’s really difficult — nearly, in some cases, impossible — because they have not tried to do so. Therefore, you’re not going to get much value out of them.

To wrap up this section: is this approach less rigorous than the scientific method? Yes. Absolutely. Where science makes claims, practitioner knowledge should give way. But that doesn’t mean practitioner knowledge is useless. And it doesn’t mean that we can’t be rigorous about evaluating it.

The Framework

Without explanation, my framework is as follows:

- Use intelligent trial and error in service of solving problems. This means two sub-approaches: first, using the field of instrumental rationality to get more efficient at trial and error. Second, using a meta-skill I call ‘skill extraction’ to extract approaches from practitioners in your field.

- Concurrently use the two techniques known for building expertise (deliberate practice and perceptual exposure) to build skills in order to get at more difficult problems.

- Periodically attempt to generalise from what you have learnt during the above steps into explicit mental models.

Of course, none of this will make sense without a framework — that is, a structure to organise these concepts and to explain why it works. So, in the next few posts, I’ll cover:

- Why we should look to rationality research as the starting point for our framework for putting mental models to practice (t)

- What instrumental rationality teaches us about reducing the cycles of trial and error needed to succeed. (t)

- How to measure if you are getting better at decision making (t)

- The epistemic underpinnings of practice (wip)

- The relationship between instrumental rationality and building expertise.

- How to apply ‘skill extraction’, with worked examples. (t)

- How to actually use deliberate practice, along with caveats, notes, thoughts, and references. (wip)

- How to use perceptual exposure in service of learning. (wip)

- How to generalise from practice to mental models. (t)

I’ve marked the above topics as (t) for topics in which I have tested through practice, or which contain arguments that I am quite confident in. I have marked the topics (wip) for topics that are still a work-in-progress in my life, or where I’m still working out the full implications of my ideas. For example, I’ve gotten quite good at writing, but I did so over a decade, and not through a rigorous process of deliberate practice. Later, I got quite good at management through deliberate practice-like techniques (over three years and in the context of engineering offices in corrupt, underdeveloped South East Asian countries) but not at the levels of rigour that are possible (and that I’m going to write about). Similarly, I only recently learnt of perceptual exposure, and am starting to apply it to my life. It will take a few years before I know the efficacy of these techniques.

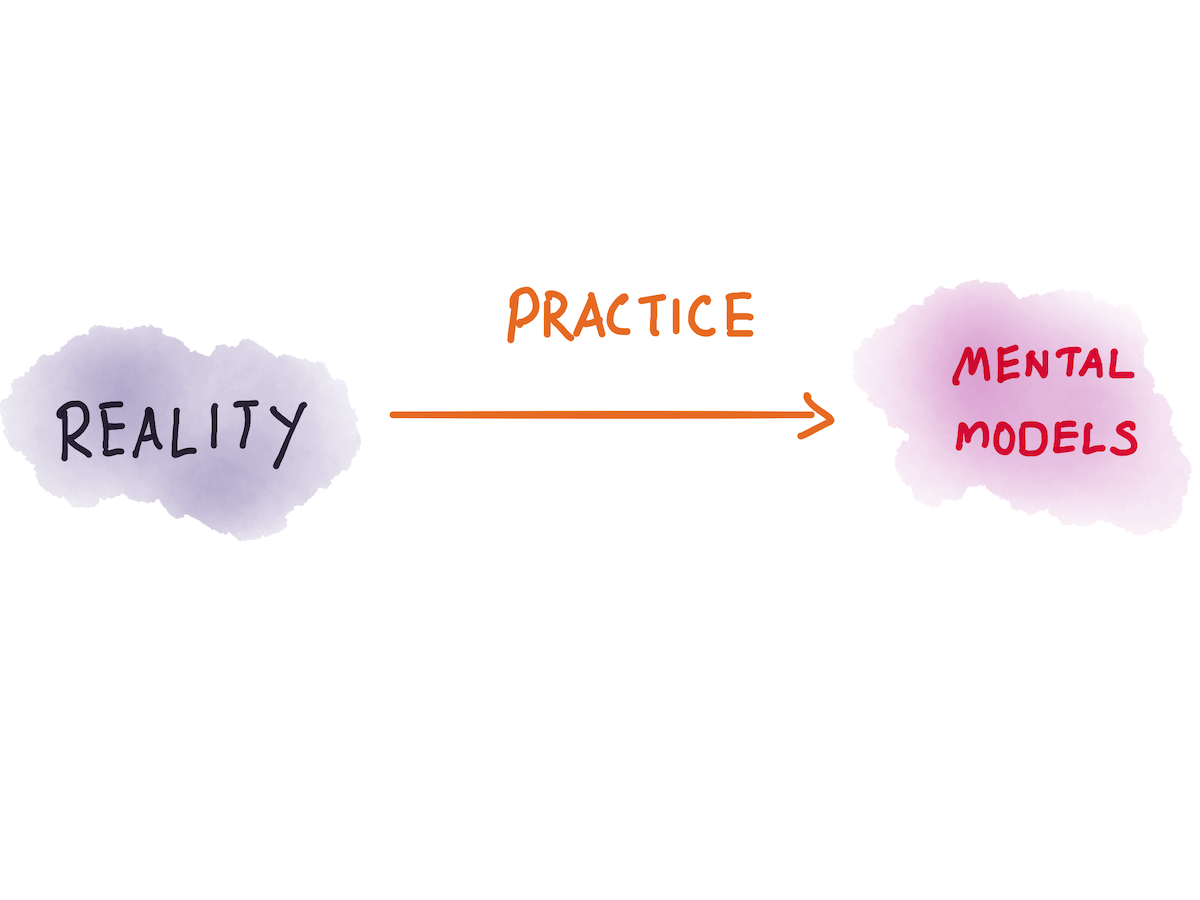

The concise summary of my approach is that I believe experience from practice leads to usable mental models.

(The alert reader will notice that this is the entire crux of Dalio’s Principles, heh).

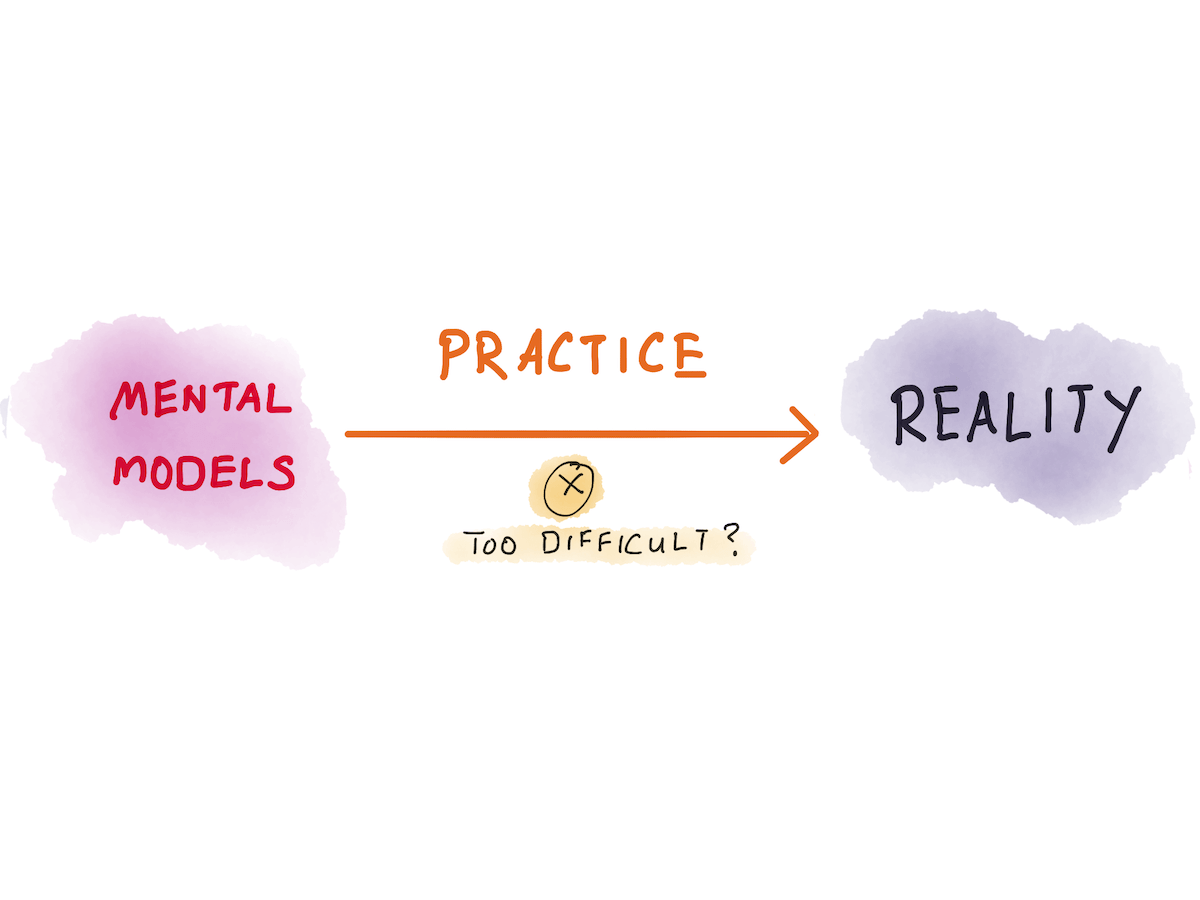

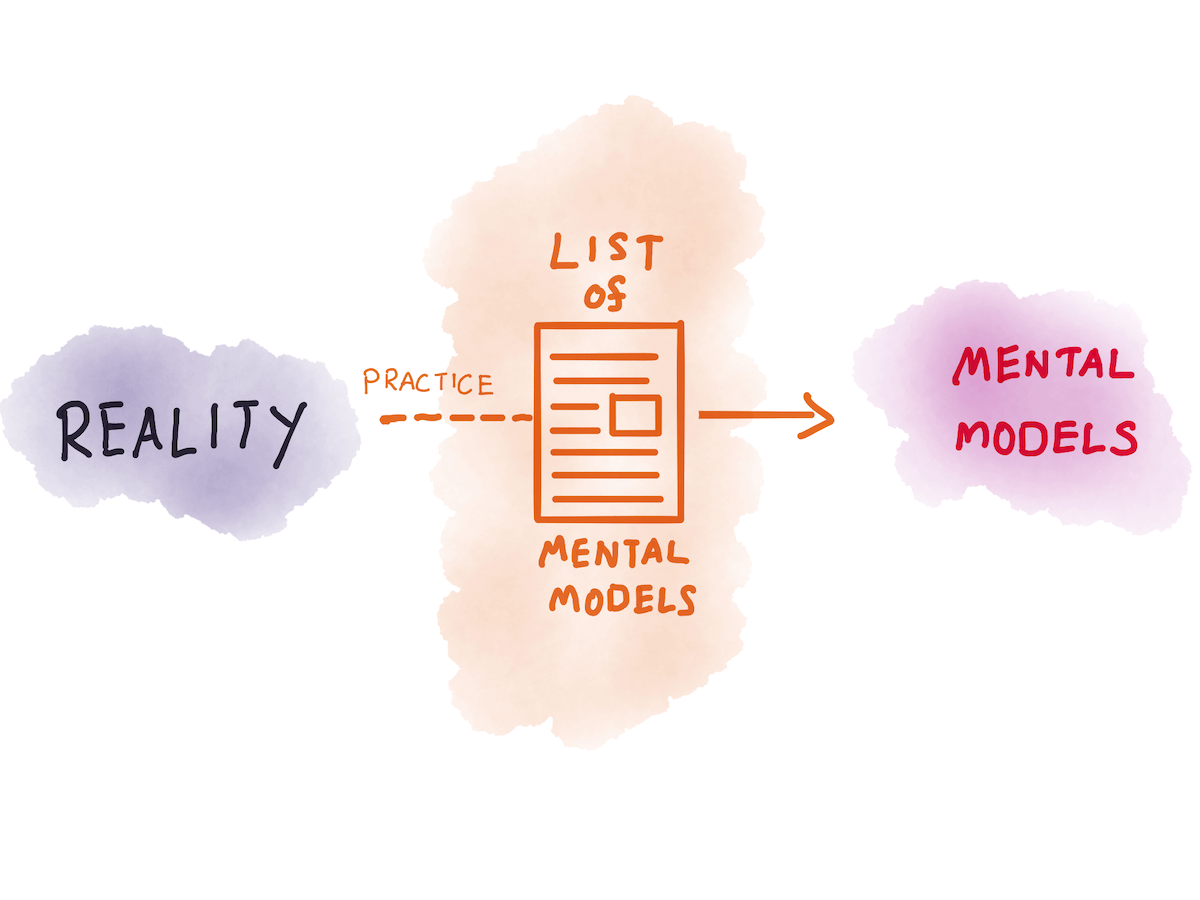

In flipping the above illustration, the alert reader will also notice that I disagree with Shane on the reverse approach, that is, using a list of mental models and attempting to apply it to reality. I think it’s too inefficient for practitioners outside finance — though I’ll admit this isn’t a very qualified opinion.

However, I will freely admit that there is something to using FS’s list of mental models to provide structure to patterns that you might notice from practice. In this scenario, reading someone else’s mental model, or looking to alternate domains for new models, occasionally results in a written description that captures some noticed patterns or intuitions from your practice. This borrowed model then gives you the ability to search the literature for similar treatments, or it gives you words to describe the things you’ve noticed in your practice.

I know I’ve certainly experienced this in relation to Shane’s writing — although admittedly very rarely.

In Part 2, we’re going to talk about the field of rationality research, and what we can learn from studying the results in that body of knowledge.

Go to Part 2: An Introduction to Rationality.

Image of Charlie Munger taken by Nick Webb.

Originally published , last updated .