At the beginning of 2019, I wrote a series on Putting Mental Models to Practice. That series was an actionable summary of the judgment and decision making literature, and existed as a constructive alternative to my criticism of mental model writing in The Mental Model Fallacy.

This post is a shortened version of the conclusions in my mental models series. It makes plain what is otherwise buried in a mountain of summarised information. I've taken some time to write this post because I wanted to dig further into Munger’s writing and world views. After about seven months of reading and research, I am satisfied that I got nothing significantly wrong in my original pieces.

Read this if you don’t have the time nor the inclination to read the full series.

What are mental models?

A mental model is a simplified representation of the most important parts of some problem domain that is good enough to enable problem solving. (This definition is lifted from Greg Wilson’s book Teaching Tech Together here.)

The origins of mental models as a psychological construct may be traced back to Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development. However, much of mental model writing today is not about Piaget’s original theory. It is instead used as a catch-all phrase to lump three different categories of ideas together:

- Frameworks. A large portion of mental model writing is about frameworks for decision making and for life. Frameworks do not sound as sexy as ‘mental model’, so it benefits the writer to use the latter phrase, and not the former. An easy exercise for the reader: when reading a piece about mental models, substitute the word ‘mental model’ for ‘framework’. If this works, continue to substitute for the rest of the piece. You will notice that the word ‘framework’ comes with restrictive connotations that the term ‘mental model’ does not. For instance, writers will often claim that ‘mental models are the best way to make intelligent decisions’ — a claim they cannot make when talking about frameworks (nobody says ‘frameworks are the best way to make intelligent decisions!’). This is understandable: writers optimise for sounding insightful.

- Thinking tools. A second, large portion of mental model writing is about thinking tools and techniques. Many of these techniques are drawn from the judgment and decision making literature, what I loosely call ‘rationality research’: a body of work that stretches from behavioural economics, philosophy, psychology, and finance. This category of mental model writing includes things like ‘reasoning from first principles’, and ‘cognitive bias avoidance’. The second part of my Putting Mental Models to Practice series concerns itself with this category of tools, and maps out the academic landscape that is of interest to the practitioner.

- Mental representations. This is Piaget’s original theory, and it references the internal representations that we have of some problem domain. It is sometimes referred to as ‘tacit knowledge’, or ‘technê’ — as opposed to ‘explicit knowledge’ or ‘epistêmê’. Such mental representations are difficult to communicate through words, and must be learnt through practice and experience. They make up the basis of expertise (a claim that K. Anders Ericsson argues in his book about deliberate practice Peak).

Today, the bulk of mental model writing is usually about one or more of these three categories of ideas.

How did mental models become so popular?

The recent popularity of mental model writing is thanks to Warren Buffett’s investing partner, Charlie Munger, and a writer named Shane Parrish.

In 1994 Charlie Munger gave a famous talk titled A Lesson on Elementary Worldly Wisdom As It Relates To Investment Management & Business. In it, Munger argues that building a ‘latticework’ of multidisciplinary mental models is key to succeeding in investing and in business. (And perhaps also in life).

Much later, Shane Parrish started popularising mental models as a method of ‘better decision making’ on his blog, Farnam Street. His list of mental models is considered the most comprehensive on the internet, and his blog is widely read by many of the most influential fund managers on Wall Street.

Why does Charlie Munger believe in mental models?

We should clarify what this means. Charlie Munger believes in building a latticework of basic (no more than first year undergrad) mental models from the various disciplines. This includes psychology, economics, biology, chemistry, physics, statistics, and math.

In Poor Charlie’s Almanack, editor Peter D. Kaufman notes that Munger was a ‘self-taught investor’, and his ‘latticework of mental-models’ approach is Munger’s solution to the difficult challenge of investing.

Why is this approach so effective? Well, think about what investing requires one to do. In order to evaluate a security, you need a passing understanding of markets, consumer psychology, investor psychology, finance, corporate accounting, trade, macroeconomics, organisational design, managerial ability, business structures, incentive structures, business law, media psychology, government interests, legislative trends, probability, and so on …

More importantly, however, you need to understand how these various concepts fit together. Munger himself makes this point most clearly with an example he uses in the various speeches he's given over the years:

I have posed at two different business schools the following problem. I say, “You have studied supply and demand curves. You have learned that when you raise the price, ordinarily the volume you can sell goes down, and when you reduce the price, the volume you can sell goes up. Is that right? That’s what you’ve learned?” They all nod yes. And I say, “Now tell me several instances when, if you want the physical volume to go up, the correct answer is to increase the price?” And there’s this long and ghastly pause. And finally, in each of the two business schools in which I’ve tried this, maybe one person in fifty could name one instance. They come up with the idea that occasionally a higher price acts as a rough indicator of quality and thereby increases sales volumes.

(…) only one in fifty can come up with this sole instance in a modern business school – one of the business schools being Stanford, which is hard to get into. And nobody has yet come up with the main answer that I like. Suppose you raise that price, and use the extra money to bribe the other guy’s purchasing agent? (Laughter). Is that going to work? And are there functional equivalents in economics — microeconomics — of raising the price and using the extra sales proceeds to drive sales higher? And of course there are zillion, once you’ve made that mental jump. It’s so simple.

One of the most extreme examples is in the investment management field. Suppose you’re the manager of a mutual fund, and you want to sell more. People commonly come to the following answer: You raise the commissions, which of course reduces the number of units of real investments delivered to the ultimate buyer, so you’re increasing the price per unit of real investment that you’re selling the ultimate customer. And you’re using that extra commission to bribe the customer’s purchasing agent. You’re bribing the broker to betray his client and put the client’s money into the high-commission product. This has worked to produce at least a trillion dollars of mutual fund sales.

(…) I think my experience with my simple question is an example of how little synthesis people get, even in advanced academic settings, considering economic questions. Obvious questions, with such obvious answers. Yet people take four courses in economics, go to business school, have all these IQ points and write all these essays, but they can’t synthesize worth a damn. This failure is not because the professors know all this stuff and they’re deliberately withholding it from the students. This failure happens because the professors aren’t all that good at this kind of synthesis. They were trained in a different way. I can’t remember if it was Keynes or Galbraith who said that economics professors are most economical with ideas. They make a few they learned in graduate school last a lifetime.

You can see that Munger’s concern is with people synthesising models across multiple disciplines, in a manner that is actually useful. This is what he gets at when he argues ‘you have to have a latticework of multiple models in your head’.

Robert Hagstrom argues that investing is the ‘last liberal art’ — and is particularly amenable to a multi-disciplinary approach. I’m not an expert in finance (and should note that Hagstrom’s various funds have either underperformed the market or shut down) but I will take his word for it. I believe Hastrom and Munger understand more about finance than I ever will.

I spend a lot of time reading about mental models, but I often find it difficult to apply to my life. Why is this so?

Mental model writing often makes claims that are confusing or overstated. This is because they conflate a bunch of different ideas together.

Writers like Shane Parrish summarise concepts from the various fields of economics, psychology, statistics, physics and biology, with the implied belief that they are generally useful (as per Munger’s speech). In truth, this approach may be of limited use outside the domain of investing.

Other writers use ‘mental models’ as a catch-all phrase to capture three different types of ideas (as I've mentioned earlier). By conflating these three categories together, they make it difficult to use them, because each idea is limited in a different way:

- Frameworks are always limited. As the statistics aphorism goes, ‘all models are wrong, but some are useful’. This applies just as much to frameworks as it does to statistical models. If we rely too much on a framework, we may miss signals that may have led us down different paths.

- Thinking tools are best applied in the domain from which they originate. They may be applied outside that domain, but you must be careful when you do so. For instance, the cognitive biases and heuristics literature warn us of our biases when making analytical decisions. However, due to the mental effort required for analysis, such techniques are not as effective in high-pressure, high-‘regularity’ domains where expertise may be built, and intuition may be relied upon.

- Mental representations are difficult — if not impossible! — to communicate explicitly. They are tacit in nature. They must be built through practice, emulation, or experience.

Breaking mental model writing into one of these three categories makes it easier to recognise their limitations, and it also helps when thinking critically about their applications.

Are mental models actually useful?

Are thoughts useful? Yes they are. Obviously.

Frameworks and thinking tools are quite clearly useful — so long as we keep their limitations in mind.

But if you take mental models to mean ‘mental representations’, then the question of whether they are useful is a silly one. It is a little like asking ‘is thinking useful?’ The answer to that is ‘well, we can’t help it, can we?’

All human beings think in terms of mental models. Piaget’s research establishes that when a toddler is learning to walk, they build a mental model of their body in their brains. (This mental model is sometimes referred to as ‘embodiedness’, and explains things like the phantom limb phenomenon in amputees). When toddlers navigate a space, they build up a mental model of physical reality. They learn concepts like ‘up’ and ‘down’, and ‘left’ and ‘right’.

Humans learn new concepts by extending mental models they already have in their heads. Piaget’s star student and successor Seymour Papert wanted to demonstrate this concept in practice. He decided to teach geometry to young children as an example of how one might do this. But Papert faced a problem: if humans learnt new concepts by first extending an existing mental model and building upon it, what mental model could be universal enough amongst children for Papert to use?

Papert realised that all young children had a mental model of physical reality. They understood concepts like ‘up’ and ‘down’ and ‘left’ and ‘right’, were old enough to understand where they stood in space, and knew how to tell people to move in that space. So he designed a programming language called Logo, and taught it to kids. In Logo, you write commands to move a turtle on a computer screen, drawing a line behind you. The actual programming language was besides the point; Papert believed that if you gave children a notation that extended this universal knowledge into ideas of lines and shapes, children would be able to form more robust mental models of geometry.

These intuitive mental models could later be formalised into mathematical notation by a teacher. Papert's experiment worked. He later wrote a book about his approach.

Papert believed that this way was the future of education — not through boring lectures in a classroom, or unintuitive geometric equations on a blackboard, but instead by building intuitive mental models first (ideally through a computer, to save labour) and then having teachers formalise that intuition into equations later.

When you say the phrase ‘mental model’, what you are doing is that you are leaning on this body of work. This has more implications than you might think.

For instance, Piaget and Papert’s notion of mental models help explain why you map abstract concepts to physical analogues in your head.

I am a programmer by training. When I read a codebase, I build a mental model of the program in my mind. My brain’s chosen representation is a set of blocks that ‘interface’ with each other. A close friend tells me that his representation is a set of pipes that carry data throughout the program. Our brains may choose different analogues, but the point here is that they are physical in nature, and individually constructed.

This practice is not limited to programmers. Practitioners in highly abstract fields like physics and math also map abstract concepts down to oddly concrete representations in their heads. Here’s the mathematician William Thurston:

How big a gap is there between how you think about mathematics and what you say to others? Do you say what you're thinking?…

I’m under the impression that mathematicians often have unspoken thought processes guiding their work which may be difficult to explain, or they feel too inhibited to try…

Once I mentioned this phenomenon to Andy Gleason; he immediately responded that when he taught algebra courses, if he was discussing cyclic subgroups of a group, he had a mental image of group elements breaking into a formation organised into circular groups.

He said that 'we' never would say anything like that to the students.

His words made a vivid picture in my head, because it fit with how I thought about groups. I was reminded of my long struggle as a student, trying to attach meaning to 'group', rather than just a collection of symbols, words, definitions, theorems and proofs that I read in a textbook.

And it doesn't stop there, of course. Deliberate practice pioneer K. Anders Ericsson argues that mental representations lie at the heart of all expert performance.

Once you understand this idea — that human expertise consists of mental models that we construct internally from things we already know — you should begin to see several implications that arise naturally from Piaget’s theory.

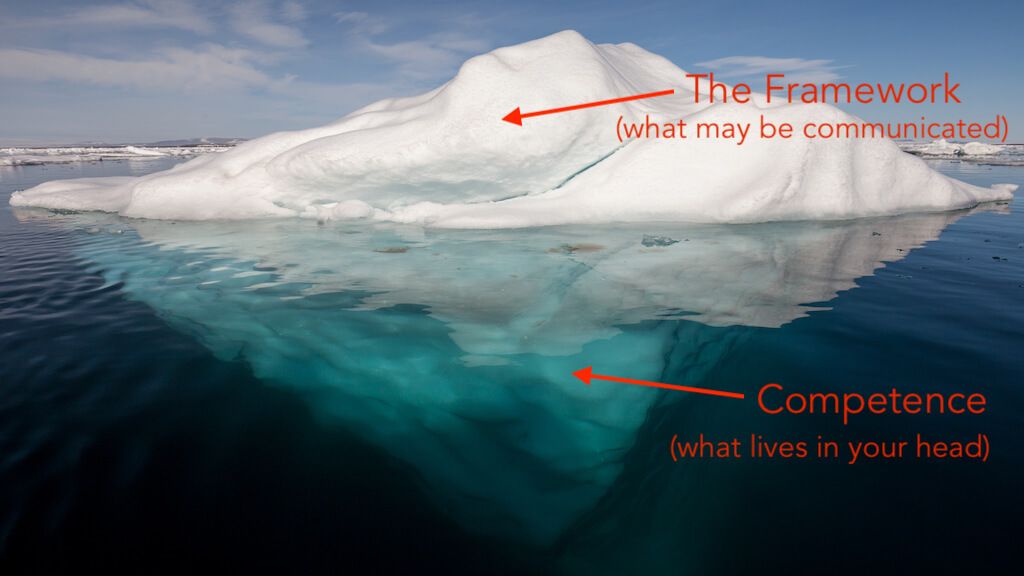

One direct implication is that frameworks do not make for competence. I can tell you my framework for employee retention, but that is not the same thing as being able to use it in your own practice.

Or, as a friend puts it (on training people in enterprise sales): “The framework is not the thing. The thing (that lives in my head) is the thing. The framework is simply our best attempt at communicating the thing.”

To state this another way, you cannot learn the mental models of experts by studying the frameworks they teach. You must construct it for yourself through practice — perhaps by using their utterances as a guide — but ultimately your own competence has to be built on what you already know.

So, yes, mental models are incredibly useful. If nothing else, they tell you that the valuable bits of expertise is not what is communicable, but what is tacit and stuck inside the practitioner’s head.

A serious practitioner would make that the object of their pursuit.

What are some general ways to put mental models to practice?

If the idea is a framework, this is straightforward: you apply it like you would any other framework.

If the idea is a thinking tool, you look for ways to try it out in your life, and see if there are any observable effects from putting it to practice. Thinking tools from more probabilistic domains (e.g. finance, political forecasting) tend to come with instructions to ‘evaluate the process separately from the outcome’. Thinking tools from more regular domains (e.g. programming, management, fire-fighting) tend to be more amenable to ‘evaluate the outcome directly’.

In academia, the cognitive biases and heuristics tradition that was pioneered by Kahneman and Tversky seem particularly well-suited to probabilistic domains (book recommendation: Thinking: Fast and Slow). The naturalistic decision making field is better adapted to regular domains (book recommendation: The Power of Intuition). I sample both in my series, and continue to believe that both domains contain techniques that are useful to the career-minded individual.

More broadly, the field of judgment and decision making are roughly divided into three models: descriptive models (how humans actually think e.g. cognitive biases), normative models (how humans ought to think e.g. probability theory), and prescriptive models (what is needed to get humans to change their thinking from the descriptive models to the normative ones). A practitioner interested in reading source material from this literature should look for publications that describe prescriptive models. (Book recommendation: Thinking and Deciding).

(I would note that the Naturalistic Decision Making field seems to be overlooked in the general self-improvement space. People tend to over-index on the ideas from the cognitive biases tradition. This means that NDM — which focuses on acquiring expert mental representations — is likely a source of competitive edge.)

Finally, the most powerful idea I believe that one should take away from ‘mental models’ as a concept is really Papert and Piaget’s work, above: that expertise is built on top of tacit mental representations, and that those mental representations are what are truly important for mastery and the pursuit of expertise.

Are mental models the secret to becoming wise?

Are frameworks or thinking tools the secret to becoming wise? No.

Do wise people operate using mental models? Yes … but this is trite: wise people are human and all humans operate using mental models.

Are the mental models of these wise people better? Yes — otherwise we would not regard them as wise.

The right question to ask here is: what beliefs do wise people have, and how can we learn those from them? When phrased this way, much of mental model writing is stripped of its novelty. Learning wisdom from the wise by working backwards from their beliefs is a pursuit that is as old as humanity itself.

Is there anything else that’s useful in the mental model literature?

I think mental model writing is generally useful. It’s true that frameworks and thinking tools are helpful ... if written by a practitioner. Such ideas are often the only explicit parts of the tacit model in their heads — sort of like the part of the iceberg that’s visible.

The cognitive biases and heuristics tradition gives us a handful of powerful tools in our toolbox. The naturalistic decision making tradition gives us an additional handful of tools. And if you are an investor, reading widely and picking up mental models (representations) from each of the various disciplines seems like a good thing to do.

But one idea that I think deserves more play is this notion that everything is a system, and if you can understand the rules of the system, you can manipulate it to bend it to your will. This is a powerful idea that pops up now and again in mental model writing, but is often taken to mean ‘study the results of the systems thinking literature’.

I believe the general idea is simpler: everything is a system and every system has rules. If you can figure out the rules of the system, then you can play to win. For instance, if you are involved in a services business (e.g. consulting, law, or investment banking), understanding the rules of the consulting business gives you a career edge over your peers. I’ve covered those rules (or at least, the bits that I can understand) in The Consulting Business Model — but the point I’m making here is that there are rules for every domain on the planet, and that you can learn them to win.

I think mental model writing has done more to advance this type of thinking than most other flavours of self improvement.

Why has mental models writing become so popular?

As far as I can tell, this is the latest iteration of an old desire. People want a key to success. They always have. In the distant past, it was the Puritan value system. Then it was business frameworks and magic quadrants. Mental models are just the latest flavour of that desire. Caveat emptor.

I don’t believe you. How do you know you’re right?

I don’t. And I am not yet believable, so it’ll probably take a decade or two to tell if I got things right.

But for what it’s worth, these opinions were developed over a few years, from my experience building a business and from systematically reading through a good portion of the judgment and decision making literature. It’s likely that I’ve thought more about this than most people. It’s also likely that I will continue to refine my thinking over the next couple of years.

If you want source material, you should probably go back to the series I wrote on putting mental models to practice. The papers and books I referenced are all linked from within the individual pieces.

But of course: caveat emptor. What is true is only what you can verify works for you.

Image of iceberg by AWeith - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

Originally published , last updated .