In economics, time preference is the notion that the value of something changes depending on whether you receive it at an earlier date as compared to receiving it a later date. That’s a really complicated way to describe something quite intuitive, so here are a few examples.

Let’s say that you want to get rich in 10 years. 10 years isn’t a lot of time, so you find yourself willing to take more risks in order to hit a higher potential return on your investments — you may invest all of your savings into Bitcoin, for instance, or start a go-big-or-go-home startup.

But if you’re, say, 25 years old, and you want to hit five million dollars in net worth by age 60, you have more time on your hands, and may be said to have a ‘longer time preference’. This means that you’re probably going to invest in very different things — things that may give you a smaller return each year, but are less risky overall. The hope is that you may compound your investments over the 35 years you have left till you hit 60.

Here’s another example. Let’s say that you visit an Oracle and she tells you that you’re going to die next year. We’ll assume that the Oracle is 100% correct, and that you know this. Your activities for the next year would look very different from if you didn’t know you were going to die — you’d probably travel to exotic places, or binge on the best movies and eat at the best restaurants, COVID-19 be damned. Whereas in a normal year, you’d be doing some mix of investing vs harvesting — ‘investing’ activities are things that would only bear fruit years down the line (like further education, or spending time with your kids), and ‘harvesting’ activities are things that would bear fruit today (like cashing out of your employee stock option plan and buying a new Tesla).

The core idea here is that your time preference greatly influences the types of activities that you do. This is a ridiculously simple idea, but it is rather useful when it comes to thinking careers.

Think Four Decades, Not Four Years

A typical career lasts about four decades. I’m assuming that an average person starts work in their mid-20s, and has a career that lasts till their mid 60s. I have friends who believe that they are never going to retire, but even they think that they would slow down in their 70s.

(As of this writing, John Malone and Barry Diller are 79 years old, and are still active players in business; Robert Kuok was active even in his 70s; Anthoni Salim is 71. I’m picking business leaders as an example because running a business is incredibly tiring; my point is that working in your 70s is still possible. Whether you want to do so is another question entirely).

So: 40 years on average. If we believe the data, most people hit their peak earning years between the ages of 45-55. Earnings then trends downwards as we near retirement age, and peters out as you stop working and withdraw from your savings.

My point is that any type of career strategy should take these numbers into account. Many of us will have a four-decade long career. The peak of our careers will occur during our late 40s to early 50s. And the stages we go through on our way to that peak will be oddly similar, if you’ve read enough biographies and talked to enough people about their careers.

The way I like to think about it is that a career span is a bit like the stages of a typical Euro board game:

- The ages of 25 to 35 are the early game. In most careers — and most Eurogames! — you earn relatively little at the beginning, and you have to grind it out to build an economic engine. (A professor once took me aside, right before I graduated, and told me “Your 20s is going to be hard, career-wise. You’re going to be kicked around a bit. Don’t let it get you down.” It was good advice).

- The ages of 35 to 55 are the mid-game. This is when you’ve mostly figured things out, and you begin entering your peak earning years. In pure Eurogame terms, the mid-game is usually the most interesting part of a game. The majority of the players would have their core point-generating engines going, and the shape of the competition becomes clear. As it happens, I enjoy talking to people at this stage of their careers — those who are at the beginning of the mid-game tend to be the ones who have reached initial mastery, and yet still have the energy to keep up with the meta.

- The ages of 55 to 65 are the end game. In a Eurogame, the endgame is when you cash in all your investments and take points. Similarly, in careers, this stage is when you stop investing in new skills, and begin harvesting all the career capital that you’ve gained over the years. This is the time to take your winnings and enjoy life.

I think about this 40 year time span a lot. When I was in my 20s, one of my friends used to say “In the span of a career, one year isn’t much” to talk about career bets; with the benefit of hindsight, I thought he got it absolutely right.

But it’s been my experience that most people don’t think about the 40 year span. I have several friends who judge our peers on their career trajectories based on what’s happened in their 20s; I have other friends who think they’re doing brilliantly two or three jobs in. But I’m a lot more conservative when it comes to such evaluations. I know — from reading lots of business biographies, and from talking to lots of people about their work — that many things can happen in the first two decades of a career. Unless you’re in the late stage of the mid-game — in the 45-55 age bracket — it’s simply too early to tell if you've had a good run of it.

This intuition should be familiar to anyone who’s played serious Euro board games. (Or really — any kind of game with a clear early/mid/end game — Civ counts, as does Dota. If you want a taste of this, get a bunch of friends and play one or two rounds of an entry-level Eurogame — I recommend Ticket to Ride, or Carcassonne, or Splendor.)

Typically, the early-game is when all the players are making their initial bets. Usually these are all investing activities, no harvesting ones; it’s unclear how these activities would bear fruit. Similarly, the first decade of most careers are often too shapeless to evaluate properly — some people experiment with random jobs in random places; others do extra degrees. It’s difficult to tell what the outcomes would be.

There's also a simpler explanation for this difficulty: if we assume that it takes around 10 years to get good at something, and a few more years to faff around and find that thing, then having the first 10-15 years of a career appear to be a bit of a wash makes a ton of sense.

If you don't believe me, it's worth calibrating a little and looking at the careers of some successful people at the end of the early game:

- At age 30, Warren Buffett had moved back to his home town and was running seven small investment partnerships, sourced from local acquaintances. This was four years after Benjamin Graham closed his partnership (leaving Buffett without a job), and a year after purchasing his five-bedroom house in Omaha. He was practically unknown at the national stage.

- At age 30, Barry Diller was Vice President of Development at ABC, and had just invented the concept of the made-for-TV movie. Today, Diller is most known for his stints at Fox Network and with IAC (which owned, amongst other things, Expedia, Vimeo, Ticketmaster and Match.com … and helped create Tinder). But at age 30, in 1972, Diller was a rising broadcast executive; cable was still regarded as a cowboy industry, and the internet wasn’t even a thing.

- At age 30, John Malone was Group Vice President of Jerrold Electronics. This was a role he got after consulting for General Instrument while he was at McKinsey — he told Monty Shapiro, then head of GI, that someone was cooking the books at Jerrold, and that “it’s going to take a lot of work to turn this around”. Shapiro replied “If you’re so smart, why don’t you come and do it yourself?” Jerrold wasn’t the job that made Malone’s name; that came two years later when he was offered the job at TCI. The rest of his career at TCI is history.

- At age 30, Robert Kuok was an agricultural trader, running Kuok Brothers Sdn Bhd. He was three years away from setting up his first joint venture with Japanese partners, and 18 years away before building the first Shangri-La Hotel.

Yes, the obvious objection to this list is that this is extreme survivorship bias, but that’s besides the point; the point I’m making here is that it’s difficult to evaluate careers at age 30 — even when you’re looking at some of the most successful people on the planet. Nearly all of these people did their most interesting work in the mid-game; for many of them, the mid-game occurred between their 40s and 50s.

Time Preferences in Careers

Thinking about careers in 40 year spans does one other thing: it gives you a way to calibrate the expected return on investment for career decisions.

Some career decisions return you benefits immediately. Think of a high-paying, prestigious job, for instance. Others don’t return benefits as quickly. For instance, spending 10 years at early Amazon* — or an equivalently operationally rigorous company — would probably set you up as a first class operator for the rest of your career (30 years!) but would mean that you’ll look like an idiot for the first 10 years of your working life.

(*Working at early Amazon was to work long hours, earn lower-than-average pay, with a large chunk of stock comp that didn’t do as well compared to the alternatives. Bezos’s “we are willing to be misunderstood for long periods of time” is the very definition of a long time preference.)

As with all such things, this is easy to say but difficult to do. Imagine how long 10 years feels like. Imagine all the prestige and salary that you’re giving up for those 10 years. And imagine your peers buying new houses or cars and moving up in some well-defined career ladder every couple of years during that first decade. Imagine some of them building up personal brands on Twitter or LinkedIn, as a result of that early success.

If you think about careers as a step-wise comparable, then taking a pay cut to build a certain set of skills seems like a bad career move. But if you think about careers as a 40-year-long game, then investing your first decade or two to build up skills and capabilities needed for the next two decades seems like a worthwhile investment.

One way I like to do this is to evaluate careers in 10-year blocks. Given a 40 year time span, each decade for the first three decades should be used to build up for the next one. You can really only stop to harvest in the third and final decade, when you’re in your late 50s (and even then — you might decide to invest for your 60s and 70s; the irony is that if you play your cards right, the compounding effect of your skills and reputation would mean that the most interesting opportunities of your career may come to you in those final decades!)

Thinking this way also means that you would be more suspicious of jobs that don’t set you up for the latter decades of your career; you might also be more suspicious of things that confer short-term career advantages. I am rather ambivalent about the concept of personal brand building for this reason — I don’t think personal brand building is a great idea, but I also don’t think it’s a bad one. In the late 2000s, I was part of the early blogosphere; I wrote one of the first web fiction blogs and was a member of the then-prestigious 9rules network. None of the luminaries from that period continue to be as famous today. The ones who have lasted have done so because they were doing interesting, valuable things outside of their blogging. What I’ve learnt from that period is that, for most people, personal brand building takes a toll over a decade-long time span; an easier way to stay interesting and relevant for a 20-30-year period is to build or do useful things, and to harvest the reputation benefits afterwards.

Investor Brent Beshore says something similar in this podcast (52:29):

(…) you always got to have the go behind the show, and you better make sure you have the go first before you have the show, or the show is not going to matter over a durable period of time, right? And I can think about some specific people in my head that have come and gone in the sort of high-notoriety realm that just didn't have anything to back it up. And they were kind of like the one-trick pony. So I think there's a lot of those dynamics that people have to be aware of.

(…) I’m going to use the most famous (example) of them, right? Which is Warren Buffett. If you think about his personal brand over time, when he was 40 years old, hardly anybody knew who he was, right? In Omaha, he was kind of becoming a big deal in his late 30s, when he first started buying the Washington Post (…) I remember the famous anecdotes like “Who the hell is that guy? Where did he come from? Who is this Warren Buffett?” And only after he sort of was discovered, meaning people had conversations with him and said, “Wow, there’s something to this guy. This guy has a spark. There’s something unusual. His performance is speaking pretty loudly,” did he really start ramping up his personal branding efforts. And oh, by the way, yes, Warren Buffett has personal branding efforts. Don’t think for a second the aw-shucks persona isn’t coined.

Time Preference in Business

(This section has been edited to remove a section I'm probably wrong about.)

Time preference is more commonly understood in business and investing.

Probably the most famous example of this is David Swensen of the Yale endowment. Swensen realised in the late 80s that university endowments are amongst the most patient forms of capital around; this patience could be turned into a competitive advantage. The basic insight that Swensen exploited was this: liquid markets are more efficient markets, but efficient markets mean that it is more difficult to generate higher returns. Therefore, go after illiquid markets instead! Swensen figured this was a natural fit for the endowment: his strategy worked because a) he had a long time preference (illiquid funds mean that you have to stay invested for a long time), b) he was able to cultivate long-term relationships with managers, who c) in some cases had a life-long affection for and loyalty to their alma-mater.

Starting in the 80s, Swensen began searching for and investing in managers whom he thought might deliver such returns. In the early years, few such funds existed, which meant that he had to become a ‘venture capitalist of venture capitalists’. As of 2019, about 60% of Yale’s endowment is allocated to hedge funds, venture capital, and private equity, with the strategy replicated in other institutions around the world. Swensen’s track record speaks for itself.

What I find most fascinating, however, is that time preference also applies to businesses. A common observation about startups is that startup timelines are compressed, thanks to the economics of venture capital.

The story goes like this: a typical VC fund lasts 10 years. VCs do not usually invest in new companies beyond the third year of a fund’s life, to ensure their latest investments have a chance to return money to LPs by the end of the 10 year period. To quote Andy Rachleff, formerly of Benchmark Capital:

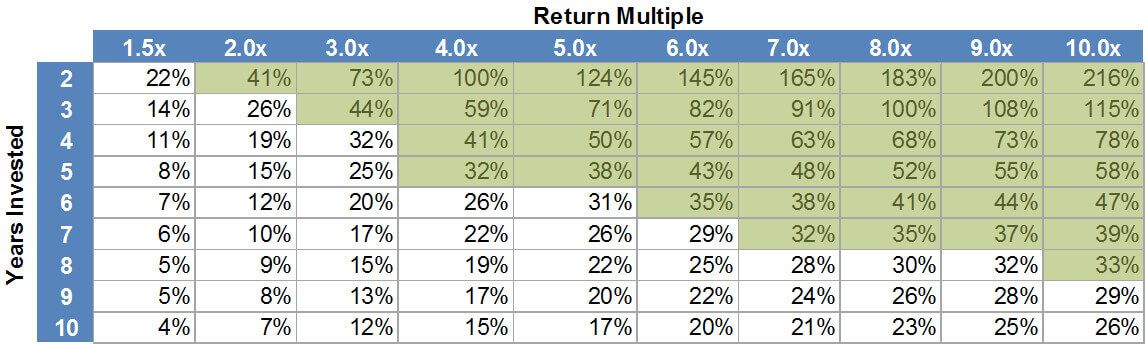

According to research by William Sahlman at Harvard Business School, 80% of a typical venture capital fund’s returns are generated by 20% of its investments. The 20% needs to have some very big wins if it’s going to more than cover the large percentage of investments that either go out of business or are sold for a small amount. The only way to have a chance at those big wins is to have a very high hurdle for each prospective investment. Traditionally, the industry rule of thumb has been to look for deals that have the chance to return 10x your money in five years. That works out to an IRR of 58%. Please see the table below to see how returns are affected by time and multiple.

If 20% of a fund is invested in deals that return 10x in five years and everything else results in no value then the fund would have an annual return of approximately 15%. Few firms are able to generate those returns.

If you’re even passingly familiar with startups, you may have heard of mantras such as ‘Startups = Growth’, or you may be familiar with the trope that startups are ‘go-big-or-go-home’. This is in many ways driven by the time preference of the investors who play in this asset class. Effectively, this means that startups are under pressure to deliver 58% valuation growth over a five year period, or perhaps a gentler 33% a year over eight years. This is a rather short time preference; many startups, in many markets, do not clear this bar. Many of them die.

But look outside startups, and you would find rather smaller growth rates, over longer time horizons. My goto example for this is Koch Industries, who says in its Vision:

(…) our Vision is to improve the value we create for our customers more efficiently and faster than our competitors. This should enable us to generate the return on capital and investment opportunities needed to achieve a long-term growth rate that doubles earnings, on average, every six years.

Doubling earnings every six years works out to about 12% earnings growth a year. Keep in mind that this is on average; the conglomerate is willing to accept that some years would be worse than others.

Koch remains an interesting example because it is so large and so powerful and its founders are considered so evil. As a case of growth with long time preference, however, Koch is difficult to beat: over the past 50 years, Charles and David Koch have managed to grow Koch Industries into the largest privately-held company in the United States, keeping all control for themselves. As Christopher Leonard documents in Kochland, by the mid-2000s, Koch Industries could not die. It was split into subsidiaries that were bulwarked from each other with strict enforcement of the corporate veil; failure in one subsidiary would never threaten the cash reserves of any other part of the empire.

And so Koch Industries grew, 12% at a time, over many decades, until it was so large that Charles Koch began manipulating the political system in the United States to his advantage.

I’ve deliberately chosen the venture-growth model to pit against the conglomerate growth model because the comparisons are so stark: you either build a go-big-or-go-home startup, compressing your wealth-seeking into a 10-year period, returning capital to investors with a relatively short time preference. Or you could choose to work patiently, maintaining full control, compounding your earnings at 12% a year on average over the course of five decades, until you eventually fund climate change denial and own large parts of the Republican party and are branded evil by half of your country.

Both paths are valid, but one path is significantly scarier than the other. Time preference matters. Use it well.

Originally published , last updated .