Note: since writing this post, we have published a comprehensive burnout guide that covers the symptoms, causes and ways to prevent burnout.

The Stevens Creek Trail is an 8 km-long nature trail for cyclists and runners, and it cuts across the cities of Mountain View and Sunnyvale and ends at Shoreline Park along the San Francisco Bay.

The first time I biked it, I was alone.

I was interning in Mountain View for the summer. I'd finished work and left the office for my daily commute — which in my case meant a cheap 200-dollar bike a friend had given me in a fit of generosity. This was a fortunate accident: California in the summer never rained, and I took full advantage of the weather. Most days I relied on the speed and focus of navigating traffic at dusk to distract myself from the work I’d left behind — the daily frustrations of fighting code and wrestling with Rails.

On this particular day, however, and on a complete whim, I took a right before the freeway overpass and entered a quiet little world of trees and birds and other runners.

The freeway vanished. I flew by trees and mossy walls, past squirrels bumming on overhanging branches, past the dry stones of the trail's namesake creek, past runners with dogs. The trail cut a natural corridor through two cities; along the way it bisected two major freeways and the Caltrain line — I was pedalling furiously now, happy and fully present on my bike, taking in the sights, and I flew over the 6:00 pm train, the carriages roaring beneath the pedals of my feet, and then I was underneath a freeway, the thud-thud sound of wheels loading onto the ramp above me, and I flew past ducks in the creek, and the Microsoft campus, large and gleaming on my left, and then the NASA Ames Research Center, rocket labs and wind tunnels and helicopters on my right, the compound so large it stretched far into the flat, brown horizon.

When I got back, I put some marinated pork chops into the oven, and then I exclaimed to my family in Whatsapp, elated and joyous: "I JUST HAD THE MOST AMAZING BIKE RIDE OF MY LIFE."

Burnout in the Valley

It seems insane that people burn out in such a beautiful place, but Silicon Valley was and still remains the beating heart of the tech industry; overwork and burnout go together, so I suppose it’s no surprise that burnout rates are high amongst the tech set. I was interning at a startup — the now defunct Kicksend — and I distinctly remember Pradeep, the co-founder, telling me “If you learn only one thing from this internship — learn this: don’t get burnt out. It’s not worth it.” The founders forced everyone to go home on time, and frowned on me coming into the office after dinner to code.

Kicksend’s two co-founders, Pradeep and Brendan, had apparently burnt out while working at a tech consulting company before doing Kicksend. This didn’t turn out too badly for them — Kicksend got into YCombinator’s Winter ’11 batch not long after they started. But the scars from the burnout still lingered. I remember one of them telling me that he couldn’t work for months after the previous job; the two co-founders shared a mysterious dislike for Panera Bread that had something to do with the overwork. (Presumably they were coding at Panera Bread for days at a time.)

I told Pradeep that I wanted to start my own company. Pradeep warned me that when I did — or even if I were working for someone else — I had to continually watch myself for signs of burnout, and to take corrective action if it ever seemed like I was about to hit my limit. This seemed important, so I committed it to memory. And then I graduated and continued working at startups.

The advice has worked. Since my Kicksend internship I’ve pulled all-nighters and worked weekends. I’ve had customers yell at me every other day for a month during a botched deployment that stretched six months. I’ve often started developing burnout symptoms, but I’ve never actually become burnt out. I’ve always dealt with the symptoms early.

I like to think that burnout is a kettle, and like any self-adjusting system you could keep it going by letting steam out occasionally. From watching friends burn themselves out after we graduated, I think Pradeep’s advice of constant self-monitoring has proven very useful. The knowledge that there’s a kettle inside you is half the battle.

A Burnout Prevention Technique

My burnout prevention technique has two components to it: detection and corrective action.

Detection is actually really easy. Once a week, introspect and ask yourself: “Do I feel resentful?” This works remarkably well, because resentment is the first sign of burnout. Feelings of resentment build over the long term, and sometimes your answer might be “a little, I’m alright” and then a few weeks pass and it’s “red alert, omfg I hate myself and I’m resentful of my work.”

I have Marissa Mayer to thank for this one: she wrote about resentment-as-root-cause-of-burnout in 2012, on Bloomberg:

Avoiding burnout isn’t about getting three square meals or eight hours of sleep. It’s not even necessarily about getting time at home. I have a theory that burnout is about resentment. And you beat it by knowing what it is you’re giving up that makes you resentful. I tell people: Find your rhythm. Your rhythm is what matters to you so much that when you miss it you’re resentful of your work.

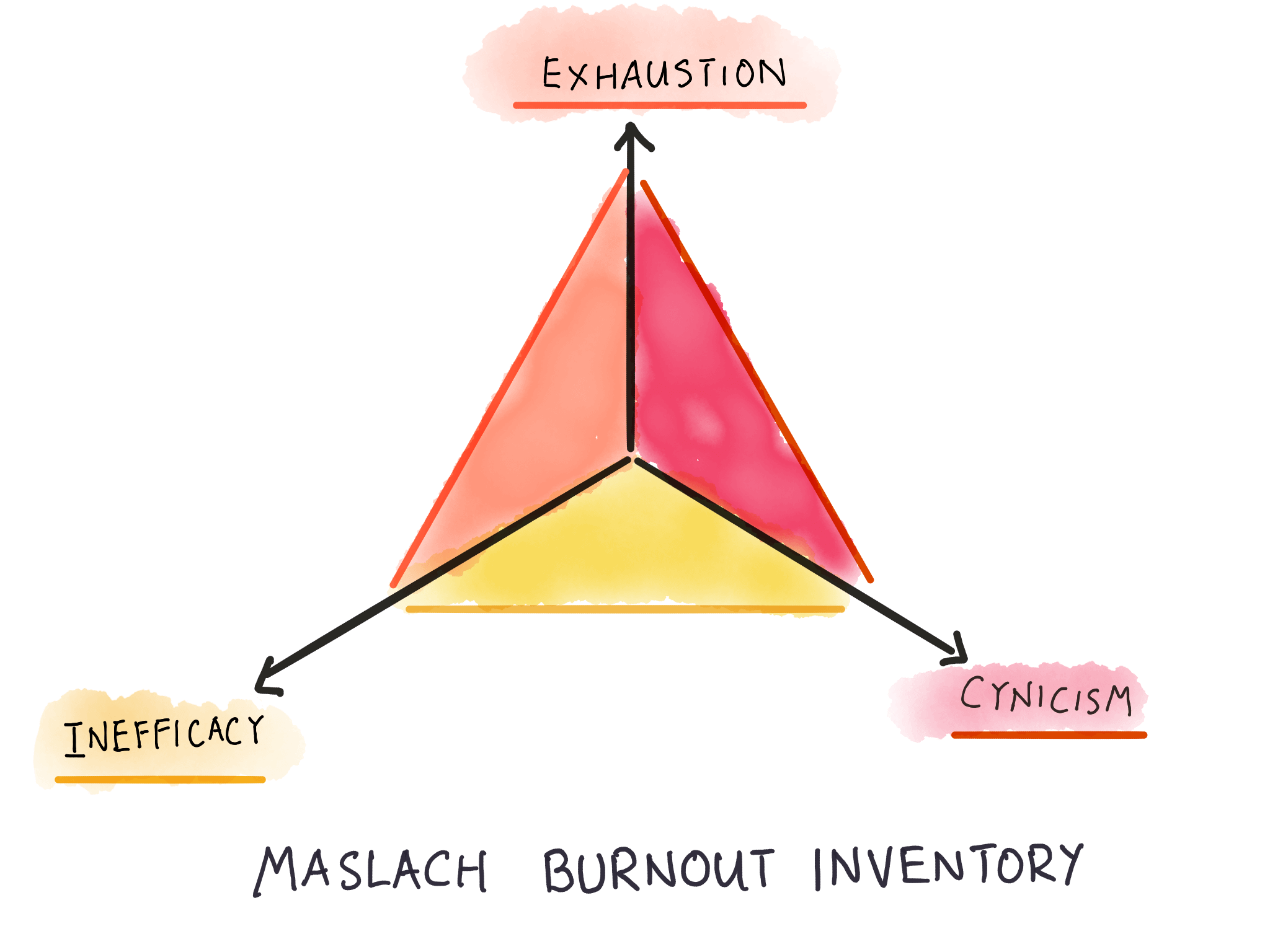

Half of what she says squares with the literature. The standard test for gauging burnout today is something called the Maslach Burnout Inventory, and it grew from research in the caregiving occupations. MBI measures what it considers the three dimensions of burnout: overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism, and a lack of personal accomplishment.

Maslach explains in a 2016 retrospective journal article:

The exhaustion dimension was also described as wearing out, loss of energy, depletion, debilitation, and fatigue. The cynicism dimension was originally called depersonalization (given the nature of human services occupations), but was also described as negative or inappropriate attitudes towards clients, irritability, loss of idealism, and withdrawal. The inefficacy dimension was originally called reduced personal accomplishment, and was also described as reduced productivity or capability, low morale, and an inability to cope.

Interestingly, Maslach notes that feelings of cynicism was the greatest predictor of turnover; early development models of burnout modelled the process as three stages:

a) job stressors (an imbalance between work demands and individual resources), b) individual strain (an emotional response of exhaustion and anxiety), and c) defensive coping (changes in attitudes and behavior, such as greater cynicism).

In other words: first your job demands too much of you, then you feel anxious and emotionally exhausted, then you cope by becoming cynical about work, and then you quit.

Marissa Mayer got one thing right: asking yourself for resentment is a remarkably effective way to gauge your degree of burnout. Resentment marks the beginning of defensive coping, which precedes cynicism, which in turn precedes Really Bad Burnout. And it turns out introspecting for resentment is a lot easier than doing the MBI; we’re pretty good at evaluating our emotional state if we make explicit time for it. (Hint: introspecting in the shower counts. Schedule it).

Unfortunately, not all burnout is caused by giving something up, and not all burnout can be beaten using what Mayer calls ‘the one thing you can’t give up’ rule.[1] Mayer seems to think that giving each employee the ‘one non-negotiable thing they must have’ would rid them of resentment and enable everyone to work as hard as she does. Presumably this is because it's how things have always worked for her. But I’ve tested Mayer’s theory in the years since I read it, and this just doesn’t work for the general case.

Restful Activity that’s Actually Restful

The thing that finally worked was this idea that some restful activities were actually restful, and others weren’t. The trick was to make time to do those activities before resentment got too far, and to do them wayyyy before cynicism showed up.

Here we fall prey to the vagueness of the English language. Restfulness might not be the right word for this; ‘recharge’, perhaps, might be better. Regardless of the word you use, there’s this mistaken belief that all leisure activities are equally good for burnout, and that what works for one person works for everyone. You hear this when someone says to you: “Come with us to the movies! Everyone needs a break from work!”

This isn’t true — watching a movie doesn’t make the mess at work more tolerable (for me). I know because I’ve tried it. Maybe it works for some friends; I once watched Dunkirk in IMAX and smelt the pee from the guy sitting one row in front — maybe he felt some release from the stress of work after the show ended. But personally, movie watching does nothing.

I’ve spent enough time observing myself to know that only three things work: one, exercise, two, travelling to new places without a tight schedule and three, meditation. There might be other activities that I haven’t found, but this is a good enough mix. It was no accident, then, that cycling the Stevens Creek Trail was so wonderful: it checked both activities one and two.

I know people for whom their restful activity is hanging out with friends; others who insist that their activity is very aggressive badminton. Whatever works for you: find it, find multiple, use them. Lower resentment before it becomes too late.

Making Value Judgments on Burnout

It was surprising to me that the literature on burnout is — as of 2016 — only two decades old. It was overly focused on the caregiver professions early on; Maslach herself says that her models overemphasised social factors and social-related exhaustion (e.g. from dealing with patients and death) in the early years.

Research into burnout and burnout prevention amongst healthcare professionals remains an ongoing, important research area. There is some urgency; Buchanan & Considine note in 2002, for instance, that half of Australian nurses leave the profession prematurely, most of them due to burnout. An undergraduate paper I found on burnout amongst the Australian nursing student population by Samantha Bella et all suggested in its conclusion that burnout resistance could be built:

However, other research suggests this is not where the problem lies. Rather, failure to recover consistently from such work stresses (in non-work time) is a crucial determinant of chronic (maladaptive) fatigue and burnout evolution (Winwood et al. 2007). When such recovery is effected consistently, physiological toughness (Dienstbier 1989,1991) and enhanced stress resistance is developed, with improved performance at work, better sleep and reduced maladaptive health outcomes (Dienstbier 1991).While some individuals may achieve this spontaneously, far more may benefit from specific training to do so effectively and consistently.

… but then the papers she cite (Winwood et all) turn out to be from her thesis advisor, so I’m not sure if this is that believable.

I mention the context of this research because burnout prevention is uncontroversial when done in the context of the healthcare profession. We assume that caregivers do noble, necessary work. But for some reason burnout prevention is treated like controversial fire in tech.

The underlying assumption being: working yourself to the bone to save lives is alright; working yourself to the bone to build the next big thing isn’t.

Perhaps there’s something to it. Perhaps there’s something morally wrong with developing coping strategies for burnout. I’ve often wondered if I was doing the world any good by putting in yet another all-nighter for a client, mentally scheduling time to decompress at the gym later in the week.

Teaching people to last longer at jobs they dislike — overwhelming, bad, unsupportive jobs — can’t be good for long term health. I’ve found my coping strategy to be remarkably effective; but at some point you have to ask yourself: is this really worth it?

That value judgment is left as an exercise for the alert reader.

Note: you can find a more comprehensive guide to burnout here.

Top photo of the Steven's Creek Trail from Caleb Gomer on Flickr, second photo from cifraser1. Both licensed under the CC BY 2.0 license.

The rule, from Ms. Mayer, goes roughly like this: if you have to keep making sacrifices for work you'll begin to feel resentful. Therefore, she'll let you have one thing that is non-negotiable that would make the biggest difference to your happiness. From Ms. Mayer's Bloomberg article: "I had a young guy, just out of college, and I saw some early burnout signs. I said, “Think about it and tell me what your rhythm is.” He came back and said, “Tuesday night dinners. My friends from college, we all get together every Tuesday night and do a potluck. If I miss it, the whole rest of the week I’m like, ‘I’m just not going to stay late tonight. I didn’t even get to do my Tuesday night dinner.’ ” So now we know that Nathan can never miss Tuesday night dinner again. It’s just that simple. You’re going to be so much more productive the rest of the week if you get that." ↩︎

Originally published , last updated .