← Head back to the Starter Manager Guide

Have you ever wished that you could go back to the good old days, before you were a manager? When your work days were long, uninterrupted periods of concentration and progress? When meetings were rare, and not something that took up the majority of your time? When you could — you know — actually plan your day?

You are experiencing what writer and programmer Paul Graham calls “The Manager’s Schedule”.

The manager’s schedule is chaotic and random, and chopped up into little one hour blocks that may change as new events occur. This is in direct contrast to the IC’s schedule — which consists of long stretches of time in order to focus and get work done.

But the problem with the manager’s schedule isn’t that the events are chaotic and random. It isn’t even that it chops up your day into little pieces. The problem is that you always have a niggling feeling at the back of your head: is this the most important task I can do right now? Is there something else that needs to be done? Am I missing something big?

The speed at which new random events enter your todo list merely compounds this fundamental problem.

More often than not you’ll end your day, go home, and then suddenly realise — in the shower! — that you forgot Bob’s code review or Jane’s specification, and now you have two engineers sitting around, blocked, unable to continue with their tasks.

That feels bad. It feels bad because you’ve affected someone else’s work. It especially feels bad because you had no way of knowing what thing was more important in the heat of the moment.

New managers often face this problem without realising that it's a problem. When you were an individual contributor, it was easy to evaluate which task was more important than which other task. Completing your assigned feature? Important. Helping John set up the new task management tool? Maybe not so important.

But when you became a manager, your ability to evaluate your work went out the window. Every task now seems equally important, so you prioritised whatever was top of mind, or whatever seems most urgent, and left the truly important tasks till later. Cue the chaos.

That’s why the ability to evaluate management tasks means so much to your sanity. You won't have a niggling feeling at the back of your head if you can instantly evaluate each new request that comes in. You'll immediately know if this new task merits your attention — compared to every other task you have on your plate at any given moment!

In this chapter we’re going to learn how to see management tasks as they truly are, and evaluate them against The Manager’s Job.

Managerial Leverage, Clarified

Earlier in this guide we talked about how the manager’s job is to increase the output of her team. I also introduced the idea of ‘managerial leverage’, which is positive when you’ve increased the output of your team, and negative when you’ve decreased it.

It’s time to be more precise: there are actually three types of managerial leverage. Let’s go through them in order.

The first type is obvious: when many people are affected by one manager.

As an example, let’s say that a feature may only be developed if an engineering manager ensures that a specification is written on time. If the engineering manager does not write a specification on time, then a team of multiple programmers would not be able to start work on that feature. By unblocking them, the manager is enabling the output of multiple people!

Conversely, the manager can negatively affect the output of those people if she doesn't get the spec done in time. This is why senior managers spend a good deal of their time simply unblocking people: they know that their failure to do so is negative managerial leverage; or more simply a failure to do their job.

The second type of managerial leverage is when work takes a manager a short time, but impacts the team or the organisation for a long time.

Performance review is a perfect example of this kind of managerial leverage. A performance review takes only a couple of hours at the most, but if feedback is given thoughtfully (and delivered effectively), the review may affect the subordinate's performance for a long time after.

The third type of managerial leverage is the least obvious type: when a large group's work is affected by an individual supplying a key piece of knowledge or information.

An example of this is the marketing manager who figures out that an ad channel is no longer producing good returns for the company. If she informs the right people in sales, she may save the organisation a huge amount of time and money chasing down leads using that channel. Another example is when an engineering manager discovers a brittle subsystem. By supplying this information to the larger organisation, the manager may ensure that nobody modifies or touches that subsystem in the short term, preventing bugs and countless hours of pain for all involved.

Managerial leverage is useful to us because we may use it to prioritise tasks that come our way.

Managerial Productivity

Broadly speaking, a manager can become more productive in one of three different ways:

- She does her work faster (that is, she does more work done per unit time)

- She increases the managerial leverage of her activities

- She changes the mix of activities so that she does more high leverage activities and less low leverage ones.

Option one is doable but not particularly sustainable (we could force the manager to drink 10x more tea, for instance, but that's hardly a workable long term solution!)

Option two is more interesting. How do you increase the managerial leverage of an activity?

Well, our first observation is that certain management activities depend on timeliness for leverage. For instance, the example of writing specs before a programmer is available to work on it is an example of timeliness. If the manager doesn’t complete the spec on time, the programmer sits idle.

An implication of ‘timing’ leverage is that you have to expend less energy the earlier you are in a process, when your leverage is higher. For instance, you may improve outcomes if you provide relevant feedback in the planning process for a new initiative, but you would have to expend a greater amount of time and energy if the project has moved past the planning stage.

Another aspect of exercising high leverage is linked to our earlier principle of always catching problems at the lowest value stage possible. Catching and dealing with an issue before it becomes a full blown problem is a perfect example of timeliness in exercising high leverage.

Early in my managerial career, I introduced a new way to do work estimations. Previously, we had been doing work estimations in an ad-hoc manner. I thought that adopting the ‘agile method’ of applying numerical values to estimates would be beneficial for our software development.

But it turned out that a couple of my subordinates thought that the process was a bad fit for the realities of our team, and started complaining to each other. I only caught this in a one-on-one with a senior engineer, weeks after the fact, and barely managed to avoid a total rejection of this new process.

My leverage could have been much higher had I paid more attention immediately after introducing the change; tweaking the process early to suit our needs would have saved me hours of work later.

Prioritisation

Let's turn our attention now to the final option: that of changing your mix of activities to favour higher leverage activities while reducing the number of low leverage activities you perform.

I've found that sitting down once a week and ranking all the tasks that I have to perform to be a highly beneficial activity. Sit down with a cup of coffee (or tea!), and list out, on a piece of paper, every task you have to perform in your current job, no matter how trivial. Then, rank each activity from one to five, five being the highest possible leverage.

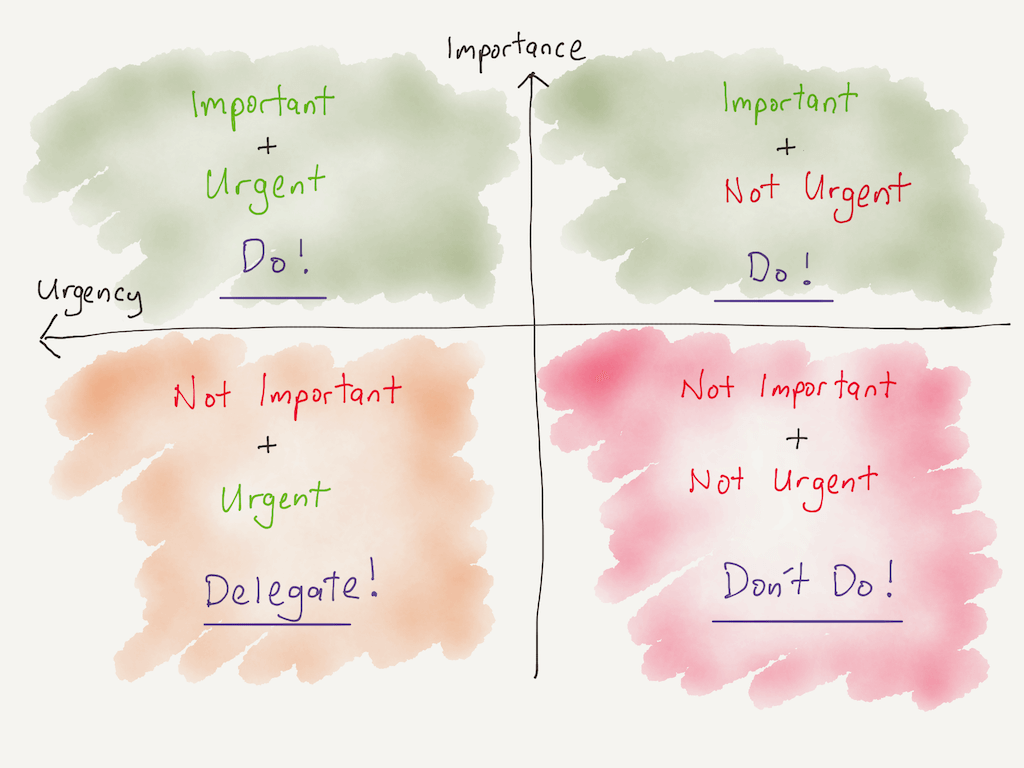

Is it possible to change your mix of activities to favour activities with high leverage? Yes, it is! Many of us are familiar with the four quadrant model of prioritisation. In a nutshell, you have two axes, importance and urgency, and you split the axes into four quadrants. They are: important and urgent, important and not urgent, not important and urgent, and not important and not urgent. You categorise your various tasks into each of these four quadrants.

Then, you apply the following actions:

- Important and urgent: you naturally do the tasks in this category.

- Important and not urgent: you should do these, but most of the time you don't because the tasks aren't urgent. This is the category you should pay special attention to, as it's easy to miss out on doing these tasks.

- Not important and urgent: you try and delegate these

- Not important and not urgent: you try to not do these.

In a manager's world, the importance axis is defined by managerial leverage. Activities with higher leverage should place higher on the importance axis.

This four quadrant model is how I prioritise. Because I keep a running tally of my tasks in my todo-list, I can quickly run this process in the morning when I first arrive in the office. This process usually takes me no more than 15 minutes after my morning cup of coffee.

Gathering information

A final word about information gathering. A huge part of managerial leverage is achievable only through having a good information base. Notice in my story above that I needed a senior engineer to tell me during a one-on-one meeting that my work estimation process was at risk of being rejected by the entire team.

As a manager, you need to think rigorously about the sources of information you gather as you do your work. Otherwise, you won't be able to apply managerial leverage in activities that have a timeliness aspect to them. You are also less likely to catch problems at the lowest value stage possible.

Gathering information occurs in a variety of scenarios:

- Informal channels like an off-hand remark by a colleague in an informal setting, or over lunch.

- Formal channels like one-on-one meetings, or project meetings.

- Written reports from distant parts of the organisation.

And so on. We may evaluate the relative values of each information channel using the lens of timeliness of information vs accuracy. These tend to be at odds with each other. For instance, informal channels tend to be extremely timely, but highly inaccurate. Consider the various channels through which you currently gain information about your organisation. What is the mix of timeliness and accuracy in your current set of sources? Are there others that you have not considered?

Actionables

Let's end this chapter with a couple of actionables.

First, perform the four quadrant analysis I've described above. List out all your activities, no matter how trivial, and rate them from 1-5 on managerial leverage. Then, slot them into the four quadrants we have seen above. What does this tell you? Does it help clarify i) which activities you need to pay special attention to? ii) provide suggestions as to what you may delegate or cut? Consider doing this activity weekly.

Second, consider the mix of activities you’re doing. Given that you’ve classified all your activities as low/medium/high leverage, create a plan of action to do more of the high leverage activities. Also consider which activities you’re going to cut.

Third, consider your information sources. Are there sources of information that you have not considered before, or are paying only a little attention to? Andy Grove wrote that he spends a portion of his time reading customer complaints while he was CEO at Intel, because he believed that it was an extremely timely information source with relatively high accuracy, and therefore a high leverage activity.

Alright, that's it for now. In our next chapter we'll explore one-on-ones, an important tool that managers use to reduce work emergencies that affect the output of their teams.

Chapter 5: One-On-Ones: How to Prevent Blowups From Happening →

If you're a Commoncog member, download the ebook copy of this guide here. If you're not a member, fill this out to get an ebook copy:

Originally published , last updated .