This post is Part 3 of A Framework for Putting Mental Models to Practice. In Part 1 I described my problem with Munger’s approach to mental models after I applied it to my life. In Part 2 I argued that the branch of academia (applied psychology, decision science, and behavioural economics) that studies rationality is a good place to start for a framework of practice. We closed our discussion in Part 2 with the observation that Farnam Street’s list of mental models were really made up of three types of models: descriptive models, thinking models concerned with judgment (epistemic rationality), and thinking models concerned with decision making (instrumental rationality). In Part 3, we will discuss putting into practice the mental models that are concerned with instrumental rationality.

Let’s begin our discussion on instrumental rationality with a discussion of trial and error, as per Part 2’s discussion of Taleb’s ideas. To be precise, we want to know what an ideal form of trial and error looks like, so we may begin to discuss what it means to be ‘instrumentally rational’ in service of applying it to our lives.

To make this section more fun to read, I’ll invent a person named ‘Marlie Chunger’, who bears zero similarity to anyone real and living. Marlie is currently on a journey to mastery in some chosen domain with ‘positive convexity’ — that is, he can afford to conduct trial and error because the costs of getting things wrong in his domain are not so great.

So let’s begin by imagining that Marlie Chunger is faced with a problem.

In order to do trial and error, Marlie marshals his thinking, and then makes his first attempt at solving the problem.

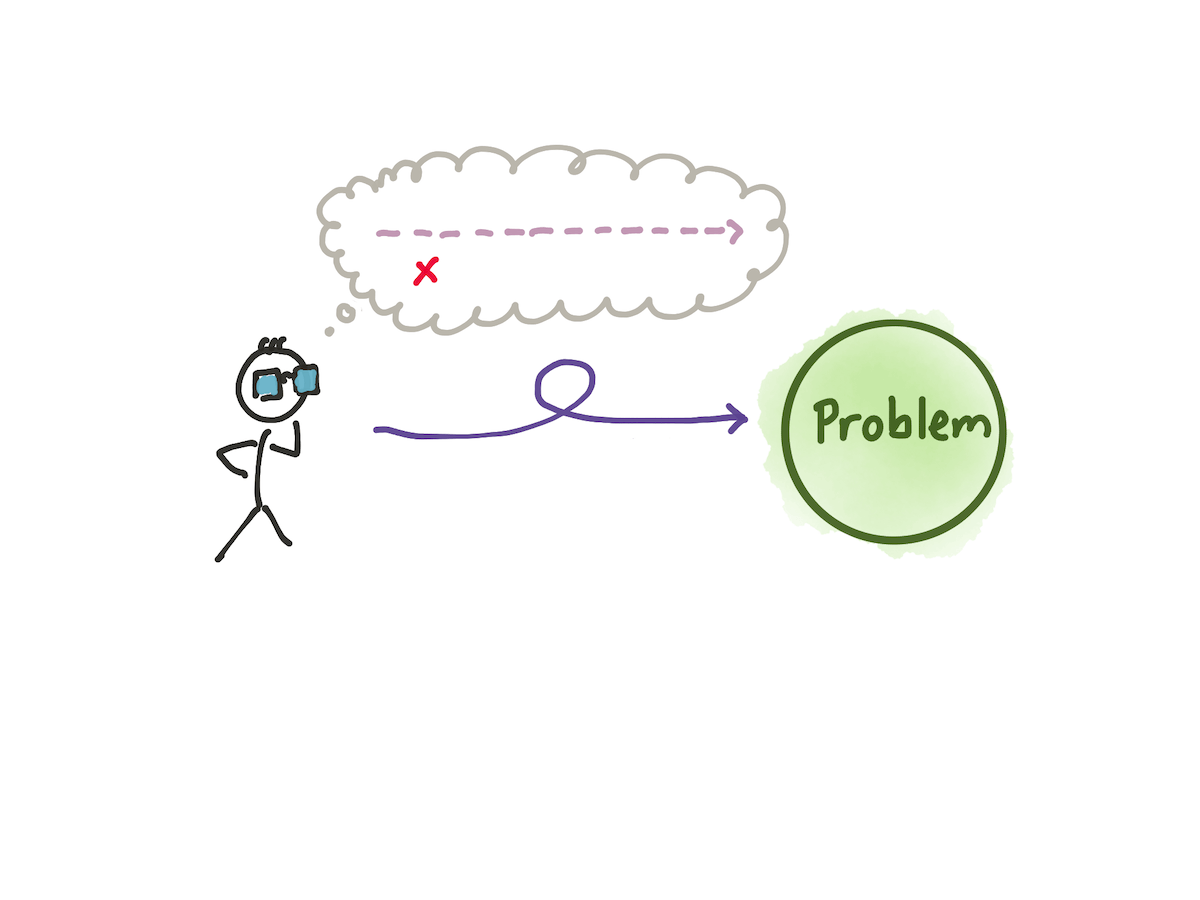

The attempt fails. Marlie reflects on the failure, draws lessons from this first, failed attempt, and then — by incorporating these lessons — tries again.

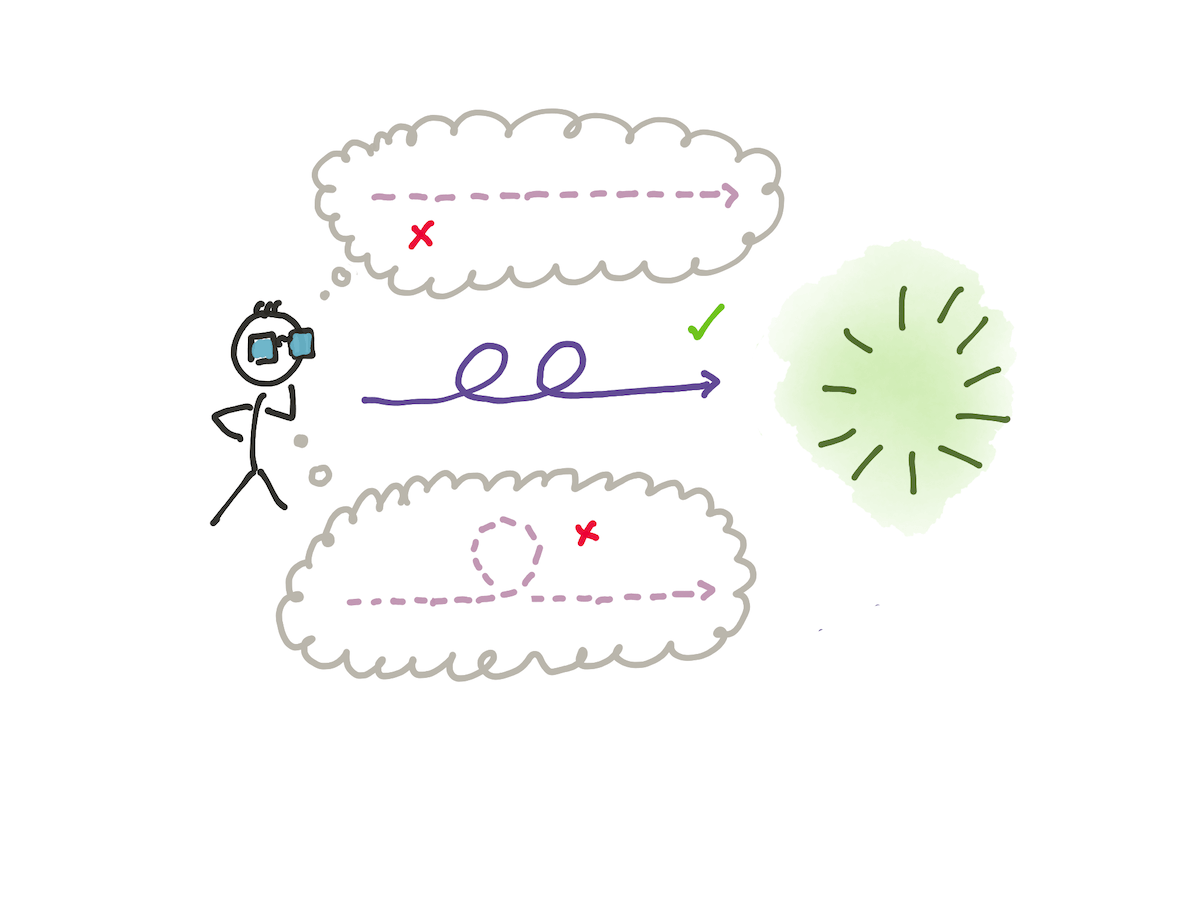

After n tries of failure and reflection, Marlie finally finds an approach that succeeds.

Marlie then reflects on the successful approach in an attempt to generalise it. He doesn’t enshrine it in his toolbox quite yet, as his success may well have been a fluke. Instead, he waits for a second problem that is much like the first to appear in his life, and attempts to apply his previously successful approach. Sometimes this doesn’t work out the way it did the first time, but it gets him 80% of the way there. By tweaking this approach, he gets it to work. He then generalises it into a ‘principle’ or ‘approach’ that is a full member of his toolbox.

(Of course, in future iterations of this problem, Marlie might find he would need to make further tweaks to his successful technique because of variations he hadn't accounted for, or perhaps in the future he might come across a new technique that is superior to his discovered approach in every given way. A fully rational Marlie would then either modify his approach by testing it, or toss out his hard-won approach in favour of the superior one).

So let’s ask: how might this process fail? By applying even a little thought, we may see that trial and error may fail for a variety of reasons:

- You may fail by blowing up — that is, you go bankrupt after one trial, or suffer a failure so bad it puts you out of the game forever.

- You select trials randomly, without ever learning from your failures. This scattershot approach means you have to rely on luck. A more likely version of this failure is:

- You select trials suboptimally, because you don’t search for relevant approaches, or you don't fully reflect on your failures to figure out what to vary for future trials. This isn’t a weakness per se, because with sufficient trials even a bad selector may eventually converge on a solution.

- You irrationally repeat the same trial over and over again, expecting different results.

- You erroneously consider the problem unsolvable, and opt to stop your cycle of trial and error.

- You never pause to generalise your working approach, and so have to continue performing trial and error when coming across a new problem that is actually similar to the current one. This robs you of the efficiency that applying an approach that has already been shown to work.

“Aha!” I hear you think. “Ideal trial and error seems easy enough to apply to my life — I just have to avoid all these problems! Stand back and watch me win!”

Not so fast. Consider for a moment the difficulty of dealing with problematic people in your life. It’s likely that you — like me — have one or more ‘personality types’ that you have trouble working with. For instance, you might dislike ‘Susan’, and have difficulty with everyone you meet who is similar to ‘Susan’, or who reminds you of ‘Susan’. You complain to your friends about ‘people like Susan’, and say “I can’t stand her! She drives me nuts!”

A disinterested observer, standing outside of your life, might suggest that your emotional cascade from dealing with ‘people like Susan’ is blinding you to the fact that you are reacting with her ‘personality type’* the same way over and over again, each time you meet someone like her in your life. Your reactions cause the same results, because of course they would. Each confirmation simply convinces you ever more that you can’t deal with people like ‘Susan’, and that you should just avoid people you think are like her, and that “it’s not worth it to try.”

* (I don’t mean ‘personality type’ here in a scientific sense. We know from research that we have all sorts of biases that cloud our judgment of people, and may in fact contribute to our problems. This is somewhat besides the point; I’m using 'personality type' in this case to describe the situations where you react to the perceived similarity of some person in bad ways.)

I bring up ‘dealing with difficult people’ as an example because it represents for many of us a vivid illustration of the difficulties of trial and error in a real life situation. For whatever reason, when it comes to working with people, we tend to fall prey to our biases, blind spots, and emotional cascades, and greatly reduce the odds of successfully applying trial and error when developing approaches to dealing with them.

Here we have our first whiff of potential problems with trial and error.Why do people make such mistakes? How do they fall into the trap of one of the five failure modes of trial and error? Can we learn models from instrumental rationality that will help us with these failure modes?

The answer is yes. But because each of these failures involve thinking in the service of decision making, we will need a framework of thinking in order to answer this question with a satisfactory amount of specificity. And so now we turn to Jonathan Baron.

A Framework for Thinking

In Thinking and Deciding, Jonathan Baron offers up a framework of thinking that allows us to analyse the prescriptive models that appear in the decision making literature (Chapter 1, pg 6). He calls it the ‘search-inference framework’, and it’s the framework that I’ve adopted for my approach to putting mental models to practice.

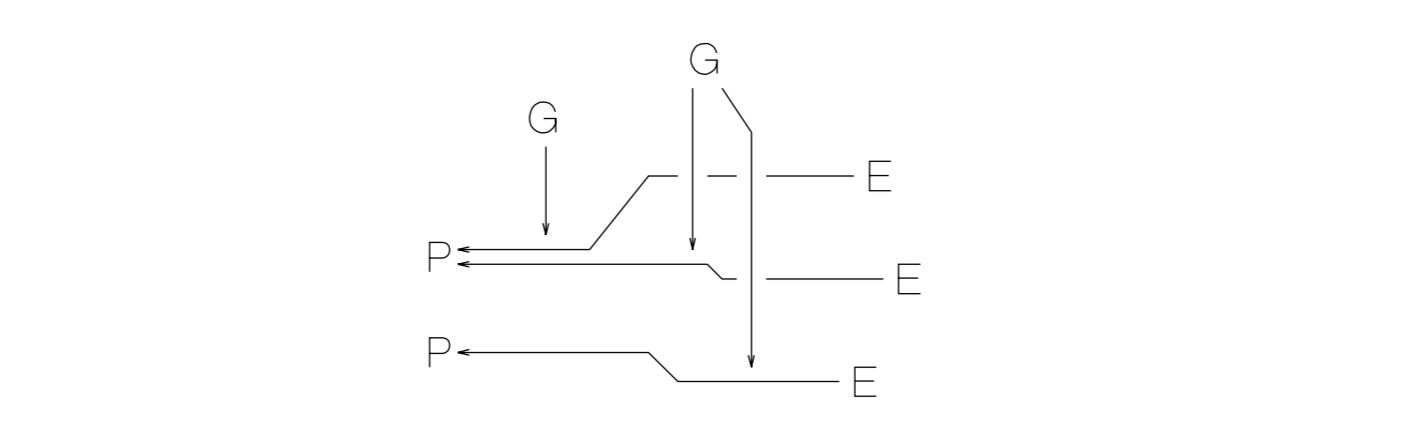

The search inference framework states that all of thinking can be modelled as a search for Possibilities, Evaluation Criteria (that Baron calls ‘Goals’), and Evidence. In addition to a process of search, a process of inference also happens as we strengthen or weaken the possibilities, by weighing the evidence we have found for each possibility in accordance to a set of evaluation criteria.

That description of the framework is a little dry, so I’ve adapted the following example from Baron’s book.

Imagine that you are a college student trying to decide which courses you will take next term. You are left with one elective to select, having already scheduled the required courses for your major. The question that starts your thinking is “which course should I take?”

You begin your search by browsing the course catalog of possible elective courses. You also ask friends for possible electives that they’ve enjoyed. One friend says that she enjoyed a course last term on Soviet-American relations. You think that the subject sounds interesting, and you’ve always wanted to learn more about modern history. You ask her about the workload, and she says that there was a lot of reading and a twenty-page paper. You realise that you can’t cope with that amount of work because of the assignments you’ll have to do for your required courses. You resolve to look elsewhere.

As you browse the list of courses on your college website, you come across a course on ‘American History After World War II’. You remember hearing about this course before, from your friend Sam. This course has the same advantage as the first course — it sounds interesting, and it is about modern history — and you think that the course work wouldn’t be too difficult. You go off to find Sam to ask her questions about your choice.

In this example we see all the elements of the search-inference framework in action. Your thinking process involves a search directed at removing your doubt. You search for possibilities — that is, possible course options — by searching internally (from your memory) and externally (from the course catalog website, and from your friends). As you perform this search, you determined the good features of two courses, some bad features of one course, and a set of evaluation criteria, such as the fact that you don’t want a heavy course load for this elective. You also made an inference: you rejected the course on Soviet-American relations because the work was too hard.

The search-inference framework, then, concerns three objects:

- Possibilities are possible answers to the original question. In this case they are the course options you may take.

- Evaluation criteria (or ‘goals’, as Baron originally calls them) are the criteria by which you evaluate the possibilities. You have three goals in the above example: you want an interesting course, you want to learn something about modern history, and you want to keep your work load manageable.

- Evidence consists of any belief or potential belief that helps you determine the extent to which a possibility achieves some goal. In this example, the evidence consists of your friend’s report that the course was interesting and the work load was heavy. At the end of the example, you resolved to find your friend Sam for more evidence about the work load on the second course.

While the example above is primarily concerned with thinking about decisions (instrumental rationality), Baron’s search-inference framework also applies to thinking about beliefs (epistemic rationality). When you think about beliefs, you are doing the same search-inference process: that is, you search for possibilities (“I believe the death penalty is moral”, or “I don’t believe the death penalty is moral”), marshal evidence in favour of each possibility, and construct a set of evaluation criteria or ‘goals’ (e.g. “I want to have beliefs aligned with my religion”) that would strengthen or weaken (or ignore!) the evidence for each possibility.

Why just these phases: the search for possibilities, evidence and evaluation criteria/goals, and inference? Baron explains:

Thinking is, in its most general sense, a method of finding and choosing among potential possibilities, that is, possible actions, beliefs, or personal goals. For any choice, there must be purposes or goals, and goals can be added to or removed from the list. I can search for (or be open to) new goals; therefore, search for goals is always possible. There must also be objects that can be brought to bear on the choice among possibilities. Hence, there must be evidence, and it can always be sought. Finally, the evidence must be used, or it might as well not have been gathered. These phases are “necessary” in this sense.

I’ve found that the search-inference framework for thinking to be incredibly useful as an organising framework for mental models of thinking. For instance: now that we have this framework, we may ask ourselves: how do we think badly? Baron argues that there are three primary ways the search-inference framework can fail:

First, the framework will fail if we don’t search properly for something that we should have discovered (that is, possibilities, evaluation criteria, or evidence), or we act with high confidence after little search. For example, in the course-selection example above, if you had not discovered ‘American History After World War II’ as a possible course option, you would not have selected it; alternatively, if you had not considered ‘light course load’ as an evaluation criteria, you would not have chosen well.

Second, we may think badly if we seek evidence and make inferences in ways that prevent us from choosing the best possibility. For instance, myside bias, ego, or a ‘desire to look good’ will prevent you from drawing the best inferences. Baron notes that this is the most dangerous form of error of the three listed here. People tend to seek evidence, seek evaluation criteria and make inferences in a way that favours possibilities that already appeal to them.

Third, the search-inference process can go badly if we think too much. Remember that good thinking and decision-making satisfies multiple goals — including the conservation of mental power. You want to spend an amount of time that is commensurate with the importance of the decision, because otherwise you would hit diminishing returns in your search and inference process. In practice, the error of thinking too much is often caused by a lack of expertise.

The search-inference framework makes all sorts of questions that you might have regarding mental models for decision making clearer. For instance: why is inversion effective? The answer, immediately offered to us by the search-inference framework, is that inversion helps us with search. That is, it allows us to search more effectively by whittling down undesirable evaluation criteria, or possibilities that get in the way of our goals. It also gives us new possibilities that we might not have considered otherwise. In this way we may say that inversion helps us with combating the first error: that is, the error of insufficient search.

The search-inference framework suggests a quick exercise that we may do: go through the list of mental models on Farnam Street, and pick out the ones that are concerned with instrumental rationality. Ask yourself: which part of the search-inference framework does this help me with?

What you’ll find is that all the mental models that concern themselves with decision making help with one or more of the three types of errors above.

Consider this also: when Charlie Munger says that ‘having a latticework of mental models’ will help you become better at decision making, what part of the search-inference framework is he talking about? What are the limitations of this approach? What are the benefits? In which fields or applications would Munger’s prescription work better, and in which fields or applications would it not?

I’ll deal more directly with the questions about Munger’s prescription later in the series. For now, however, I’d like to turn to the great mystery of putting instrumental rationality to practice: how do you know that you’re getting better at decision making? And, in a roundabout way, why did LessWrong not get very far on this very question?

What Does The Research Consider ‘Good Decision Making’?

I’ve mentioned in Part 2 of this series that LessWrong’s approach to epistemic rationality was to reach into the literature on judgment and decision making and draw out prescriptive and normative models for practice. This approach works rather well when used on the study of epistemic rationality, because so much of the practice of epistemic rationality is to find systematic biases and squash them. But I’ve asserted that it deals rather badly with the field of instrumental rationality — that is, the field of decision making.

Why is this the case?

To answer this, we need to take a look at the normative approach that the field of decision science has used in order to evaluate good decision making. The dominant approach in decision science is something called expected utility theory, which was created by Daniel Bernoulli in 1738. It asserts that a person acts rationally when they choose that which maximises their utility — that is, whatever decision it is that brings them the most benefits in pursuit of their goals.

(There is a secondary claim in Bernoulli’s original theory, which is the concept of risk aversion. For example, if you were gambling and had become rich, you would become more and more risk adverse with each additional bet, because the additional utility of money you might win would not be as valuable to you as when you were poor. We call this ‘marginal utility’ today, and expected utility theory is the first instance someone came up with this idea. This is not related to our discussion; I’m just leaving this here for completeness.)

Utility in the sense of expected utility theory is not the same as pleasure or goodness. It does not mean optimising for money, or happiness. You might be reminded of Jeremy Bentham’s conception of utility in Utilitarianism, but this isn’t exactly that either. Instead, utility represents a measure of goal achievement — and it respects whatever goal it is that you want to achieve.

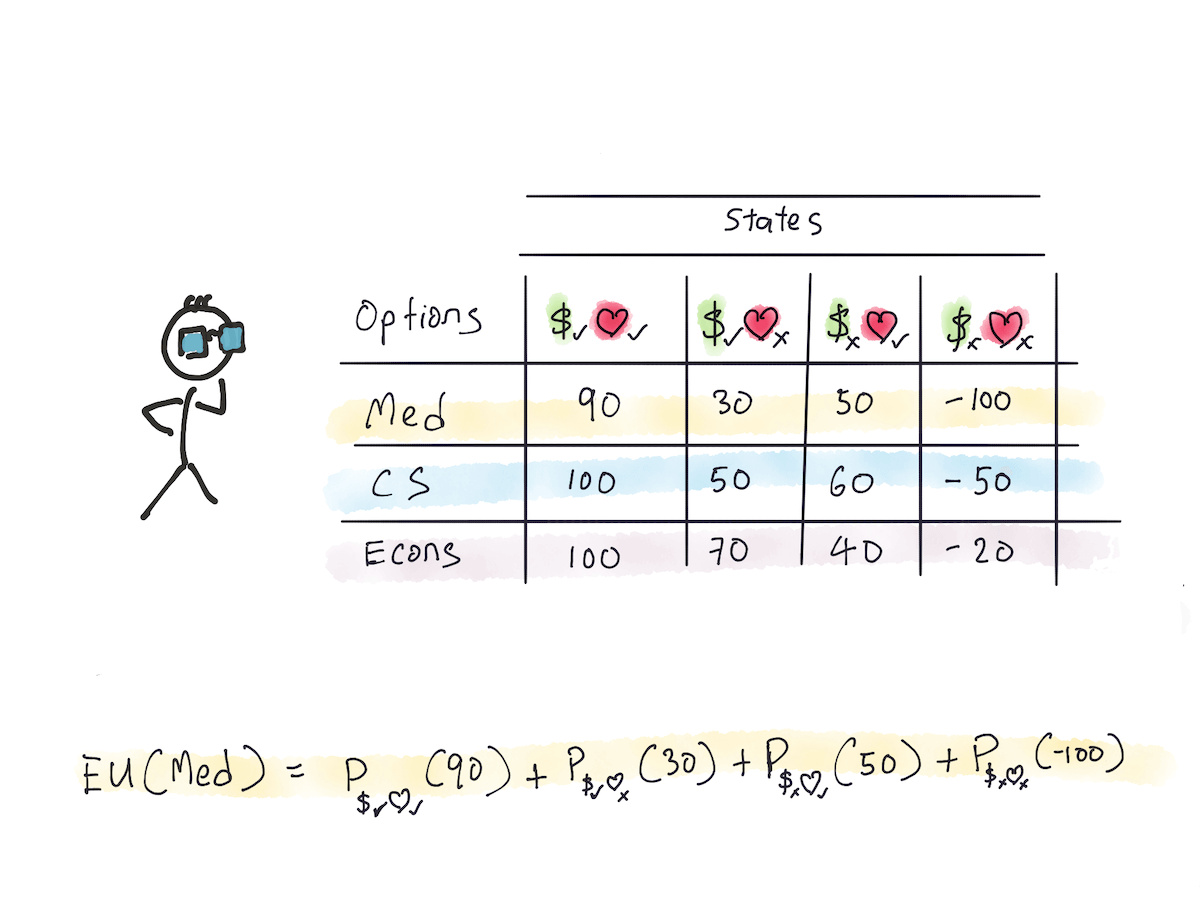

For example, if your goal is to “make lots of money doing work you love”, and you are given the choice of doing a degree in Medicine, Computer Science, or Economics, expected utility theory asserts that the best choice in this case is the one that best allows you achieve your goal of “making lots of money doing work you love”. The way that expected utility theory is applied here is that it gives a probability to each state of the world that might exist, and for each state, multiplies that probability by the expected utility of the state. The overall expected utility for a given option is the sum of all the states and probabilities.

In this illustration, each cell contains a utility value. I’ve given arbitrary values for each of the three options given the four possible states of the world: a state in which you make lots of money and love your work, a state in which you make lots of money but hate your work, a state in which you make no money but love your work, and a state where you make no money and you hate your work. Notice that it doesn’t matter what the scale is for these utility values — you merely have to ensure that the scale is consistent across the three options.

The expected value calculation of selecting Medicine, then, is the sum of the product of multiplying the probability of each state with the utility value of each state.

Applying these probabilities to each state of the world and coming up with these utility values is an act of judgment — which is, of course, fallible. But if you choose the option with the highest utility, you would be said to be instrumentally rational.

Now, I can already hear the alarm bells going off in your head. “Can you even measure utility? Isn’t any attempt to measure utility doomed from the beginning, because of real-world uncertainty? What if you change your goals midway, like you suddenly realise that Medicine isn’t for you the first time you see the insides of a real human?”

These are all valid objections. Let’s deal with them quickly.

First, expected utility theory is about inference, not search. It assumes you have all the decisions laid out before you, and it concerns itself with what you currently know at this point in time. If you gain more information later, or decide to change your goals after inserting a urinary catheter for the first time — that isn’t a problem for the theory, since all it says is that you have chosen rationally at a point in time in the past, given the information that you had then.

Second, you are absolutely right in that judging utility is difficult — nearly impossible! — in real-world situations. But one way decision scientists have gotten around this is to show that, so long as you follow the Von Neumann-Morgenstern axioms, you may be said to have acted in ways that maximised your utility. In other words, so long as you don’t violate certain ‘rules’ (which the fancy shmancy academics call ‘axioms’ because they really like math), you may be considered instrumentally rational without worrying about your ability to judge actual utility.

The Von Neumann-Morgenstern axioms are sometimes called the ‘axioms of choice’. Of these, the two most important are the ‘axiom of completeness’ and the ‘axiom of irrelevant alternatives’. The other axioms follow logically from these, so we won’t discuss them.

The axiom of completeness, sometimes called the ‘principle of weak-ordering’ is the idea that you must have an order of preferences when making decisions. It doesn’t matter if each decision has a multitude of pros and cons, or that you find it very difficult to state your preferences for them; you simply must have a preference — this is the requirement we impose. For instance, if you are given the choice of Medicine, Computer Science and Economics, you must order them in some way: for instance, that you prefer Medicine to Computer Science, and Computer Science to Economics. You are also allowed to be indifferent to some of these choices, e.g. “I prefer Medicine to Computer Science, but I don’t care if you give me Computer Science or Economics. They’re both equivalently bad in my mind.”

The first axiom also implies ‘transitivity’, which is just a fancy way of saying that if you prefer Medicine to Computer Science, and Computer Science to Economics, you must also prefer Medicine to Economics. You can’t say “oh, I prefer Economics to Medicine”, because this means you are crazy.

The second axiom is the idea that you should ignore irrelevant alternatives that have no bearing on your decisions. The simplest example I’ve found is from Michael Lewis’s The Undoing Project, which goes something like:

You walk into a deli to get a sandwich and the man behind the counter says he has only roast beef and turkey. You choose turkey. As he makes your sandwich he looks up and says, “Oh, yeah, I forgot I have ham.” And you say, “Oh, then I’ll take the roast beef.” (…) you can’t be considered rational if you switch from turkey to roast beef just because they found some ham in the back.”

It may seem trivially easy to follow these axioms, but Kahneman and Tversky’s work on Prospect Theory shows us that humans violate these two principles in all sorts of interesting (and systematic) ways. This finding implies that humans are naturally irrational, even in straight-forward decision making problems of the sort tested by their research program. But it also implies that being able to make decisions in ways that don’t violate these axioms is quite the achievement indeed.

A naive approach is to assume that one may simply take this model of instrumental rationality and apply it to one’s life. This is, in fact, what LessWrong tried to do. And in this, I believe that LessWrong has failed miserably.

What Do Expert Practitioners Really Do?

It’s safe to assume that expert practitioners make better decisions on a day-to-day basis than a novice in their domains. If you assigned a decision scientist to them, and have them follow their every move as they make decisions for whatever domains they are in, we should expect to find that they deviate less from expected utility theory than less successful practitioners given similar goals.

(There are some problems with this assertion, because — as per Taleb and Mouboussin, these practitioners could merely be lucky. But we shall ignore this for now).

So let’s consider: how do they achieve their results? The answer isn’t that they applied the methods of expected utility theory as a prescriptive model. Nobody really expects Warren Buffett to sit down and do utility calculations for all of the decisions he is about to make — this would mean he would have little time to spend on anything else.

While expected utility theory is sometimes used for decision analysis — especially in business and in medicine — it is too impractical to recommend as a general decision-making framework. As Baron puts it: “search has negative utility”. The more time you spend analysing a given decision, the more negative utility you incur because of diminishing returns.

The second problem with using expected utility theory as a personal prescriptive model is that, in the real world, judgments and results actually matter. I’ve described a method for evaluating instrumental rationality independent of goals or proper utility judgment — that is, we simply check to see if someone has violated the axioms of choice. But instrumental rationality is not the goal in the real world. Achieving your goals is the goal of better decision making in the real world. You want to ‘win’, not simply ‘get better at a measure of instrumental rationality’.

The blind spot that LessWrong had, I think, is that none of them were practitioners — of the sort that might go after worldly goals. They were, as Patri Friedman put it, “people who liked to sit around talking about better ways of seeing the world”. They were interested in the clean, easily provable results of judgment and decision making research, and less interested in looking at the messy reality of the world to see how expert practitioners actually put rationality to practice.

So how do expert practitioners put rationality to practice?

The answer is that in many fields, they do not.

The Trick

What you might not have noticed is that I've just played a trick on you.

I have combined two world views of decision making into one essay. The first view, hinted at by my illustration of Marlie Chunger, is the world view of Nicholas Nassem Taleb, Herbert Simon, and Gary Klein: a view that I’m going to lump together under the banner of Klein’s field of naturalistic decision making. This world view stems from the premise that we cannot know the state of the world, that we do not have the mental power to make comprehensive searches or inferences, and that we should build our theories of decision making by empirical research — that is, find out what experts actually do when making decisions in the field, and use that as the starting point for decision making.

This view strives to build tacit mental models via ‘experience’ or ‘expertise’ — that is, through training, practice, or trial and error. It strives for ‘satisficing’ a set of goals, not ‘optimising’ for some utility function. It is antithetical to the study of mental models independent of practice. This view sees heuristics — the same sorts of heuristics that lead to cognitive biases — as strengths, not weaknesses.

The second view is the view of Munger, Baron, Tversky, Kahneman, and Stanovich: that of rational decision analysis. This is the world view that we have explored for most of this essay. It assumes that you want to make the best decisions you can, perhaps because they are not reversible. It asserts that you can strive to achieve the modes of thought dictated by expected utility theory, which is designed to optimise your decisions with regard to your goals. It gives us a framework of thinking, and tells us that we may apply mental models to our decision making processes in order to prevent the three problems of the search-inference framework. It prescribes building a latticework of mental models, because building this latticework assists us with search — and sometimes with inference.

You can probably tell that I sit more with the Taleb and Klein view of the world, as opposed to the Munger and Baron view. But both are valid, and needed. Shane’s defence of his methods is fair: there is a place for the elucidation of mental models independent of practice.

Why is this the case?

Consider the examples of decision making that we’ve considered above. Questions like ‘what course should I choose for my next term?’ are trivial, perhaps, but there are more important decisions in life like “should I move to Tokyo?”, “should I take that job?” and “what degree should I pick?” that will determine the shape of our lives for years to come. These decisions lend themselves well to the mental models of instrumental rationality. We need to conduct sufficient search, and we must guard against our biases when inferring conclusions from evidence.

Instrumental rationality also lends itself to the sort of thinking that makes for efficient trial and error. With proper search and inference, we may prevent ourselves from falling into one of the five failure modes that we’ve covered when we discussed Marlie Chunger.

But this is not all there is to it. Perhaps you might have noticed that I’ve not talked about the approaches that Marlie Chunger keeps in his toolbox. These approaches — built by trial and error — are mental models, are they not? They allow Marlie to solve problems in pursuit of his goals.

However, they are not the kind of mental models that may be put into the search-inference framework that Jonathan Baron proposes. These approaches are intuitive. They belong to ‘System 1’, Kahneman’s name for the system that produces fast thinking. These models are tacit, not explicit, and they perform very differently from the search and inference methods of explicit thinking. We often call them ‘expert intuition’. They make up the basis of expertise.

Let me state the question that has bugged me in the years since I tried to put Munger’s talk to practice in my life, and failed. If rational thinking and good decision making are so important, how is it that an entire generation of Chinese businessmen have build a variety of successful businesses in South East Asia — in the face of racial discrimination, immigration, and the after-effects of colonisation, with nearly no education and little demonstrable rationality?

We could say that they were lucky. But attributing their success to luck is not useful to us. What intrigues me is that I’ve seen some of these businesspeople up close, and they commonly demonstrate wisdom in their decision making, built on top of intuition and (in Robert Kuok’s words) ‘rhythm’. I do not believe these are perfect decision makers. I think they would perform terribly at Kahneman and Tversky’s cognitive bias tests, and I think they would fail if they were pit against investors like Munger, in a field like stock picking. But in the fields of business that they are in, where trial and error are possible, ‘good enough’ expert intuition seem to also lead to successful outcomes. Optimal search and inference thinking can’t be all that’s at work here.

We should find out what it is.

Conclusion

I must close this essay with an apology. I know that I promised a good answer to the normative question “how do I know that I’m making better decisions?” But I had too much ground to cover, and ran out of space.

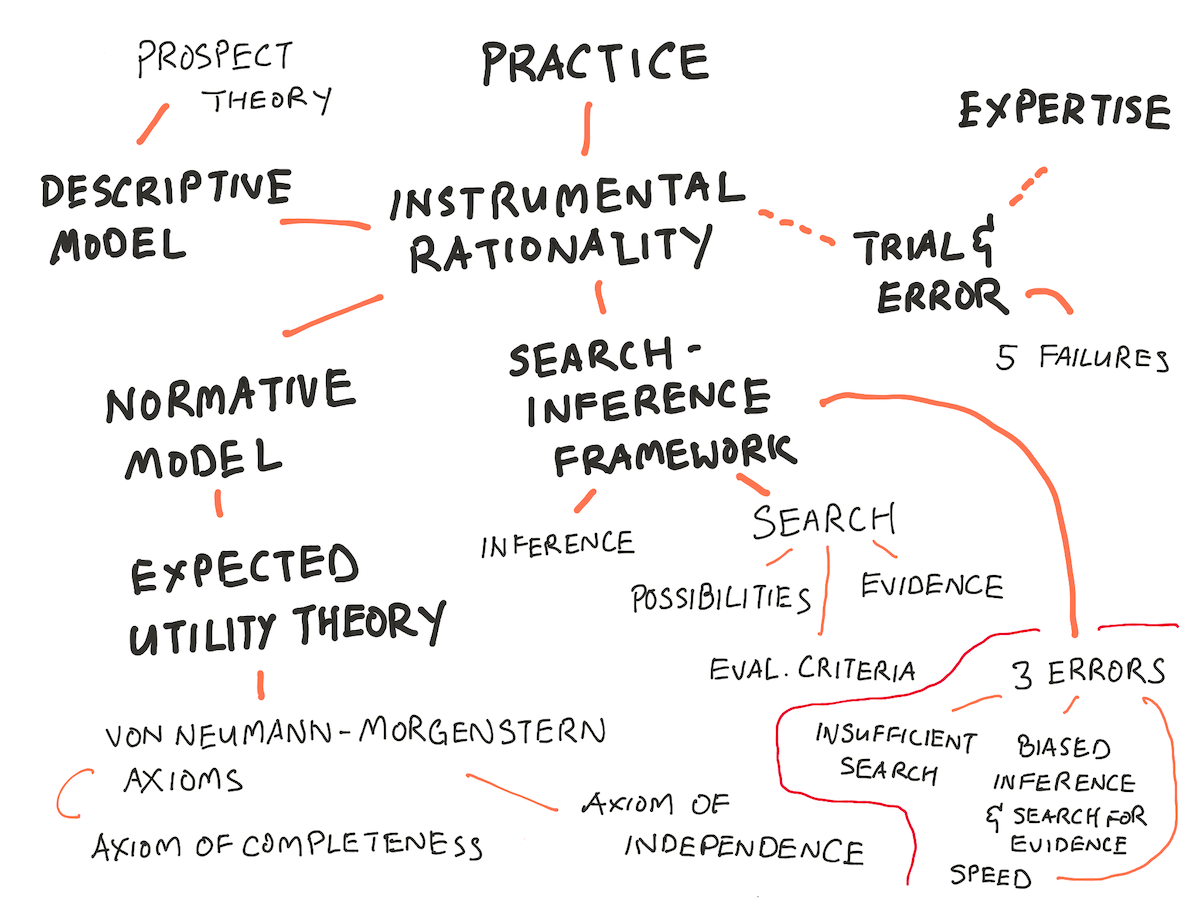

What have we covered in this essay? We’ve covered the basics of trial and error, and the five ways it may fail. We have covered Baron’s search-inference framework of thinking, and used it as an organising framework for mental models of decision making. We have covered the foundations of decision science — or at least, the foundations of decision science as related to instrumental rationality. You now understand the basics of expected utility theory — the normative model that is used as the goal of mental models in decision making.

As per usual, here is a concept map of what we’ve covered:

How do these concepts help you with practice? I believe that Baron's Search-Inference Framework gives us a template to analyse our thinking. You may now organise your search for techniques that will help you in preventing one of the three errors — for example, you may search for mental models that help you perform more efficient search, or mental models that will help prevent your biases from affecting your judgment. If you've made a bad decision, you may now introspect and ask yourself: which of the three errors have I committed? What biases did I display when attempting to do deliberative decision making?How might I conduct better search in the future?

More importantly, you now understand that deliberative decision making is just one of two decision making approaches. There is another, less discussed form of decision making, and it will be the topic of our next essay.

Next week, we’ll talk about building expertise, and the kinds of decision making that emerges from it. (I should note that the tension between expert intuition and decision-making rigour has been covered by Shane on Farnam Street many, many times in the past.) Finally, I hope to tie things up by giving a good normative goal for practice — or at least, one that seems to work well for me.

Go to Part 4: Expert Decision Making

Originally published , last updated .