This is the final part of a series of posts on putting mental models to practice. In Part 1 I described my problems with Munger’s prescription to ‘build a latticework of mental models’ in service of better decision making, and then dove into the decision making literature from Parts 2 to 4.

We learnt that there is a difference between judgment and decision making, and that the field of decision making itself is split into classical decision theory and naturalistic methods. Both approaches fundamentally agree that decision-making is a form of ‘search’; however, classical approaches emphasise utility optimisation and rational analysis, whereas naturalistic approaches think satisficing is enough and basically just tell you to go get expertise. In Part 5, we looked at some approaches for building expertise, in particular eliciting the tacit mental models from expert practitioners around you.

Part 6 brings this series to a close with some personal reflections on the epistemology of practice. I promised to write a treatment in the first part of this series, and so here we are. This begins with a simple question, and ends with a fairly complicated answer. And so here we go.

When someone gives you advice, how do you evaluate that advice before putting the ideas to practice?

It must be obvious to us that some process exists in your head — you don’t accept all the advice you’re given, after all. If your friend Bob tells you to do something for your persistent cough, you’re more likely to listen to him if he were an accomplished doctor than if he were a car mechanic.

Choosing between a doctor and a mechanic is easy, however. In reality, we’re frequently called to evaluate claims to truth from various sources — some of them from well-meaning people, others from consultants we’re willing to pay, and still others from third-hand accounts, or from books written by practitioners wanting to leave some of their knowledge behind.

Could we come up with better rules for when we should listen to advice, and when we should not? The default for many people, after all, is to just go “I trust my gut that she’s correct.” A slightly better answer would be to say “just look at what the science says!”, or “look at the weight of evidence!” but this throws you into a thorny pit of other problems, problems like ‘are you willing to do the work to evaluate a whole body of academic literature?’ and ‘how likely is it that the scientists involved with this subfield were p-hacking their way to tenure with fake results?’ and ‘is this area of science affected by the replication crisis?’ or ‘are contemporary research methods able to measure the effects I’m interested in applying to my life, without confounding variables?’ and ‘does science have anything to say at all with regard to this area of self-improvement?’

These are not easy questions to answer, as we’ll see in a bit. But it does seem like it is worth it to sit down and think through the question; the default of ‘I’ll go with my gut’ doesn’t appear to be very good.

Why epistemology?

First things first, though. I think it’s reasonable to ask what an essay on epistemology is doing in a series about putting mental models to practice. We’ve spent parts 1 to 5 in the pursuit of practical prescriptive models, so why the sudden switch to epistemology — something so theoretical and abstract?

There are two reasons I'm including this piece in the series. First, coming up with a standard for truth keeps me intellectually honest. I wrote in Part 1 that I would provide an epistemic basis for this framework by the time we were done, so that you may nail me against the ideas that I have presented here. This is that essay, as promised.

Second, an epistemic basis is important because it separates this framework from mere argumentation. What do I mean by this? Well, just because something sounds convincing doesn’t make it true. As with most things, what makes something true is not the persuasiveness of the argument, or even the plausibility of it, but whether that thing maps to reality. In our context — the context of a framework of practice — what makes this framework true is if it works for you.

This seems a little trite to say, but I think it underpins a pretty important idea. The idea is that rhetoric is powerful, so you can't simply trust the things that you read.

I wonder if many of you have had the experience where you read some non-fiction book and came away absolutely convinced of the argument presented within, only to read some critique of the book years later and come to believe that that critique was absolutely true.

Or perhaps you've read some book and are absolutely convinced, but then realise, months later, that there was a ridiculously big hole in the author’s argument, and good god why hadn't you seen that earlier? I'm not sure if this happens to you, but it happens to me all the time, and it's frequent enough that I'm beginning to think that I'm not good enough to be appropriately critical while reading.

My point is that sufficiently smart authors with sufficiently good rhetorical skills can be pretty damned convincing, and it pays to have some explicitly thought-out epistemology as a mental defence.

You can perhaps see the sort of direction I’m taking already — I’ve spent a lot of time in this series saying variants of ‘let reality be the teacher’. The naive interpretation of this doesn’t work for all scenarios — for instance, it’s unclear that ‘let reality be the teacher’ would work when it comes to matters of economic policy, despite claims to the contrary (you can’t personally test the claims of each faction, and though all sides cite research papers and statistics to back up their positions, you should realise that divining the truth from a set of studies is a lot more difficult than you think.)

But ‘let reality be the teacher’ works pretty well when it comes to practical matters — like self-improvement, say, or when you’re trying to evaluate a framework for putting mental models to practice. It works because you have a much simpler test available to you: you try it to see if it works.

The Epistemology of Scientific Knowledge

Before we dive into the details of putting practical advice to the test, let’s take a look at the ‘gold standard’ for knowledge in our world. For many people the gold standard is scientific knowledge: that is, the things we know about reality that’s been tested through the scientific method. Philosophy of science is the branch of academia most concerned with the nature of truth in the scientific method.

(“Oh no,” I hear you think, “He’s going to talk about philosophy — this isn’t going to be very useful, is it?”)

Well, I’ll give you the really short version. There are two big ideas in scientific epistemology that I think are useful to us.

The first idea is about falsification. You’ve probably heard of the story of the black swan: for the longest time, people thought that all swans were white. Then one day Willem de Vlamingh and his expedition went to Australia, found black swans on the shore of the Swan River, and suddenly people realised that this wasn’t true at all.

The philosopher David Hume thus observed: “No amount of observations of white swans can allow the inference that all swans are white, but the observation of a single black swan is sufficient to refute that conclusion.” Great guy, this Hume, who then went on to say that we could never really identify causal relationships in reality, and so what was the point of science anyway?

But what Hume was getting at with that quote was the asymmetry between confirmation and disconfirmation. No amount of confirmation may allow you to conclude that your hypothesis is correct, but a single disconfirmation can disprove your hypothesis with remarkable ease. Therefore, the scientific tradition after Hume, Kant, and Popper has made disconfirmation its core focus; the thinking now goes that you may only attempt to falsify hypotheses, never to prove them.

Of course, in practice we do act as if we have proven certain things. With every failed falsification, certain results become more ‘true’ over time. This is what we mean when we say that all truths in the scientific tradition are ‘conditionally true’ — that is, we regard things as true until we find some remarkable, disconfirming evidence that appears to disprove it. In the meantime, the idea is that scientists get to try their darnest to disprove things.

Let’s take a moment here to restate the preceding paragraph in terms of probabilities. Saying that something is ‘conditionally true’ is to say that we can never be 100% sure of something. Instead, we attempt to disprove our hypotheses, and with each failed disconfirmation, we take our belief in the hypothesis — perhaps we start with 0.6 — and increase it in increments. Eventually, after failing to find disconfirming evidence repeatedly, we say “all swans are either black or white” but our confidence in the statement never hits 1; it hovers, perhaps, around 0.95. If we find a group of orange swans, that belief drops to near 0.

(Hah! I’m kidding, that’s not what happens at all; what happens is that scientists who have invested their entire careers in black and white swans would take to the opinion pages of Nature and argue that the orange birds are not swans and can you believe the young whippersnappers who published this paper!? Science is neat only in theory, rarely in practice).

This incomplete sketch of scientific epistemology is sufficient to understand the second idea: that is, the notion that not all scientific studies are created equal. Even a naive understanding of falsifiability will tell us that no single study is indicative of truth; it is only the broad trend, taken over many studies, that can tell us if some given hypothesis is ‘true’.

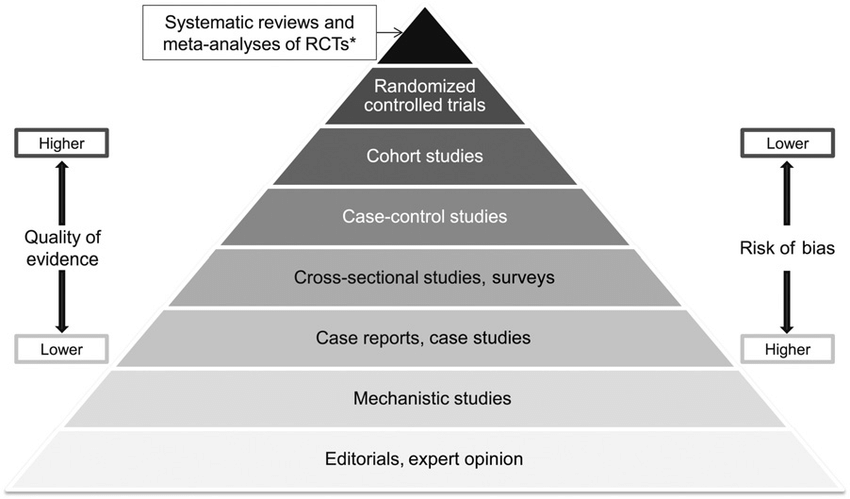

This notion is most commonly called ‘the hierarchy of evidence’, and it is usually presented in the following form:

The pyramid of evidence that you see above is most commonly taught to healthcare professionals, and it shows us the various types of studies we may use when we need to make a judgment on some statement — for instance, “does smoking cause lung cancer?” or “is wearing sunscreen bad?” At the bottom of the pyramid are things like editorials and expert opinion, followed by mechanistic studies (efforts to uncover a mechanism), then case reports and case studies (basically anecdotes), then cross-sectional studies and surveys (“are there patterns in this population?”) then case-control studies (“let’s take two populations and examine patterns retrospectively”), then cohort studies (“let’s take two populations that differ in some potential cause and observe them going forward to see if bad things happen”), then randomised controlled trials (“let’s have a control group and an intervention group and see what happens after we intervene”) and then, finally, at the tippy-top, we have systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which studies the results of many studies.

So: ‘is sunscreen harmful?’ If you’re lazy, the answer is to dive into the academic literature for a systematic review, or better yet: a meta-analysis. Meta-analyses in particular are the gold standard for truth in science; these studies are essentially a study of studies — they summarise the results from a broad selection of papers, and weight the evidence by their statistical power. It is possible to do a bad meta-analysis, of course, for the same reasons that null-hypothesis statistical tests may be misused to prop up crap research. But by-and-large, the scientific system is the best method we have for finding the truth.

It’s unfortunate, then, that large bits of it aren’t terribly useful for personal practice.

The Problems with Scientific Research as Applied to Practice

Let’s say that you’re trying to create a hiring program, and you decide to look into the academic literature for pointers. One of the most well replicated results in psychology is the notion that conscientiousness and IQ are good predictors of job performance. So, the answer to your hiring problems is to create an interview program that filters for high conscientiousness and high IQ, right?

Well … no.

This is a pretty terrible idea — and I should know: thanks to my lack of statistical sophistication, I’ve tried. The objections to this are two-fold. First, statistical predictors don’t predict well for a given individual. Second, science often cannot lead us to the best practices for our specific situation, because it is only concerned with effect sizes that are large enough to be detected in a sizeable population.

These two objections are specific to the scenario of hiring, but can also be made more generally when you are applying scientific research to your life. I’ve found that they share certain similarities with the challenge of evaluating expert advice … so let’s examine them in order.

The first problem with applying scientific research to practice is the nature of statistical predictors. Let's talk about IQ. We know that IQ correlates with job performance in a band between 0.45 and 0.58, with the effect being stronger in jobs with higher complexity. And this is IQ we’re talking about, one of the strongest results we can find in all of applied psychology; literally thousands of studies have been done on IQ over the past four decades, with dozens of meta-analyses to pick from.

Can we trust the correlations? Yes. Can we use them to predict individual job performance given an IQ score? No.

Why is this the case? In Against Individual IQ Worries, Scott Alexander explains with a comparison to income inequality:

Consider something like income inequality: kids from rich families are at an advantage in life; kids from poor families are at a disadvantage.

From a research point of view, it’s really important to understand this is true. A scientific establishment in denial that having wealthy parents gave you a leg up in life would be an intellectual disgrace. Knowing that wealth runs in families is vital for even a minimal understanding of society, and anybody forced to deny that for political reasons would end up so hopelessly confused that they might as well just give up on having a coherent world-view.

From a personal point of view, coming from a poor family probably isn’t great but shouldn’t be infinitely discouraging. It doesn’t suggest that some kid should think to herself “I come from a family that only makes $30,000 per year, guess that means I’m doomed to be a failure forever, might as well not even try”. A poor kid is certainly at a disadvantage relative to a rich kid, but probably she knew that already long before any scientist came around to tell her. If she took the scientific study of intergenerational income transmission as something more official and final than her general sense that life was hard – if she obsessively recorded every raise and bonus her parents got on the grounds that it determined her own hope for the future – she would be giving the science more weight than it deserves.

And this is actually a really pragmatic thing to do.

I have a friend in AI research who reacts to IQ studies in exactly this manner; he recognises, intellectually, that IQ is a real thing with real consequences, but he rejects all such studies at a personal level. When it comes to his research work, he assumes that everyone is equally smart and that scientific insight is developed through hard work and skill. And there are all sorts of practical benefits to this: I believe this framing protects him from crippling self-doubt, and it has the added benefit of denying him trite explanations like “oh, of course Frank managed to write that paper, he’s smarter than me.”

The point here is that for many types of questions, science is often interested in what is true in the large — what is true at the population level, for instance — as opposed to what works for the individual. It is pragmatic and totally correct to just accept these studies as true of societal level realities, but toss them out during day-to-day personal development. My way of remembering this is to say “scientists are interested in truth, but practitioners are interested in what is useful.”

A more concrete interpretation is that you should expect to find all sorts of incredibly high performing individuals with lower than average IQs and low conscientiousness scores; the statistics tell us these people are rarer, but then so what? A correlation of 0.58 only explains 34% of the variance. If your hiring program is set up for IQ tests and Big Five personality traits, how many potentially good performers are you leaving on the table? And while we’re on this topic, is your hiring program supposed to look for high scorers in IQ and conscientiousness tests, or is it supposed to be looking for, I don’t know, actual high performers?

This leads us to our second objection. Because scientific research is interested in what is generally true, most studies don't have the sorts of prescriptions that are specifically useful to you in your field. Or, to apply this to our hiring problem, it’s very likely that thoughtful experimentation would lead you to far better tests than anything you can possibly find in the academic literature.

Here’s an example. One of the things I did when designing my company’s hiring program was to use debugging ability as a first-pass filter for candidates in our hiring pipeline. This arose out of the observation that a programmer with good debugging skills might not be a great programmer, but a programmer with bad debugging skills could never be a good one. This seems obvious when stated retrospectively, but it took us a good amount of time to figure this out, and longer still to realise that a debugging skill assessment would be incredibly useful as a filtering test for candidates at the top of our funnel.

Is our debugging test more indicative of job performance in our specific company than an IQ test or a conscientiousness test? Yes. Is it a proxy for IQ? Maybe! Would we have found it in the academic literature? No.

Why is this the case? You would think that science — of all the forms of knowledge we have available to us — would have the best answers. But it frequently doesn’t, for two reasons. First, as previously mentioned, scientific research often focuses on what is generally true, not on what is prescriptively useful. I say ‘often’ here because the incentives have to align for there to be significant scientific attention on things that you can use — drug research, for instance, or sports science, for another. In such cases, science gives us a wonderful window into usable truths about our world.

But if the stars don’t align — if there is a dearth of attention or if there are a lack of financial incentives for certain types of research questions, you should expect to see an equivalent void of usable scientific research on the issue. My field of software engineering is one such field: the majority of our software engineering ‘best practices’ are constructed from anecdotes and shared experiences from expert programmers, who collectively contribute their opinions on ‘the right way to do things’ … through books, blog posts, and conference talks. (Exercise for the alert reader: what level of the hierarchy of evidence do we software engineers live in?)

The hiring example also illustrates this problem perfectly. When it comes to hiring, all we have are statistical predictors: that is, correlations between a measurement of some trait on the one hand (IQ, conscientiousness, grit) and some proxy for job performance (salary, levelling, peer assessments) on the other. As we’ve seen previously, statistical predictors are good for research purposes but are not very useful at the individual level; what we really want is some kind of intervention study, where a process is developed and then implemented in both an intervention group and a control.

This isn’t the least of it, though. The second reason science is often not useful to the practitioner is that even when there are financial incentives to perform ‘instrumentally useful’ research, there may still be a void of usable recommendations, for the simple reason that science moves relatively slowly.

Here’s an example: I’ve long been interested in burnout prevention, due to a personal tendency to work long hours. Late last year I decided to dive into the academic literature on burnout. Imagine my surprise when I discovered that the literature was only two decades old — and that things were looking up for the field; Buchanan & Considine observed in 2002 that half of Australian nurses leave the profession prematurely, the majority of them due to burnout. In other words, the urgency of finding a solution to burnout is now really, really high, and medical institutions with deep pockets are beginning to push researchers forward. This is the sort of attention and financial incentives that lead to instrumentally useful scientific research — the sorts that you and I can apply directly to our lives.

So, what have they found? After two decades of study, they have developed a test for detecting burnout — the Maslach Burnout Inventory — and they have two developmental models for how burnout emerges and progresses in individuals. (You can read all about it in this ‘state of the field’ summary paper that Maslach published in 2016). What they haven’t discovered is a rigorous system to prevent burnout.

(Some people believe that inverting the developmental models gives us generally useful prescriptions for our workplaces. This is because the developmental models tell us how burnout progresses, which should then give us clues as to arresting that progression. But! Remember the caution of ‘generally useful’ interventions from our earlier discussion, and keep in mind where this lies in the hierarchy of evidence).

What interests me the most, however, is the small branch of the research that focuses on burnout resistance training — that is, the idea that individuals who experience burnout and recover from it develop better resilience to burnout later. I have high hopes for this branch to develop into something useful, but the only way to know is to give it another decade or so. Such is the price for truth.

The point here is that going for thoughtful trial and error in fields where scientific knowledge exists isn't a ridiculous position to take. It's trite to say “oh, I don't see why you can't take what psychologists have figured out and apply it to your practice” — but the answer is now easier to understand: science is interested in what is generally true, and it often doesn't give good prescriptions compared to what you (or others) can derive from observation and experimentation; worse still, if you start out with a model of reality drawn from some science and are convinced that the model is more valid for your unique situation than it actually is, you're likely to hold on to that model for longer than it is useful.

Of course, this is just a really complicated way of saying that some forms of knowledge are best learnt from practitioners — if you want to learn a martial art, you go to a sensei; when you want to learn cooking, you learn from cooks, not food scientists. Don’t start out with epistêmê when it’s technê that you’re interested in learning.

Of course, I don’t mean to say that scientific knowledge isn’t useful for personal practice; I think it’s pretty clear that instrumentally useful research exists, and wherever available we should defer to those results. But I am saying that understanding the nature of truth in scientific knowledge matters, and it doesn’t absolve us of the requirement to test things in our realities. If a doctor prescribes Adderall to you and you find that it puts you to sleep — this doesn’t mean that Adderall is useless or that amphetamines should be reclassified as sleep aids. In fact, you shouldn’t even be that surprised; statistical truth tells us that most people would feel stimulated on Adderall; lived experience reminds us that individual variation is a thing. Even scientifically proven interventions fail to work for some people some of the time.

Evaluating Anecdata

I’d say that the major takeaway at this point is that you never know if something might work until you let reality be the teacher and try it out for yourself. But it’s worth asking, though: if individual variation is this much of an issue when it comes to applying scientific research, how much worse can it get when we’re dealing with expert opinion and anecdotal evidence?

The question is worth asking because most spheres in life require us to work from evidence that’s nowhere near the rigour of science. Consider my example of hiring, above: in the absence of solid science, one obvious move that I can take is to talk to those with experience in the tech industry, in order to pick their brains for possible techniques to use for myself. As it is for hiring, so it is for learning to manage difficult subordinates, for learning to start and run a company, and for learning to use martial arts in real world situations. In situations where you are interested in the how-to of things, you often have only two options: first, you can go off and experiment by yourself, or second, you can ask a practitioner for their advice.

So how do you evaluate the advice you’re given? How do you know who to take seriously, and who to discount?

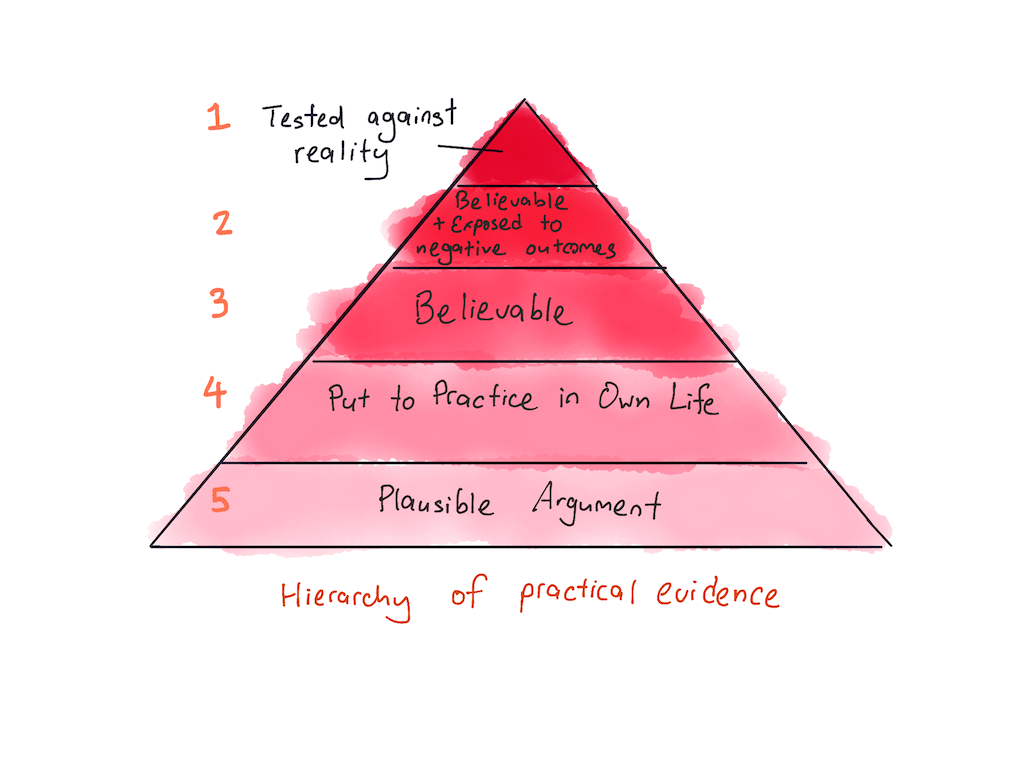

I’d like to propose an alternative hierarchy of evidence for practitioners. When asking for advice, judge the advice according to the following pyramid:

At the very top of the pyramid is advice that you’ve tested in your life. As I’ve repeatedly argued during this series: “let reality be the teacher!” You only truly know that a piece of advice works if you have tested it; the same way that a doctor will only truly know if a drug works after a patient has started her course of treatment. Before actual action, all one can have is a confidence judgment in how likely the intervention would work.

The second level of the pyramid is advice from practitioners who are believable and who are exposed to negative outcomes. Believability is a technique that I’ve already covered in a previous part in this series: originally proposed by hedge fund manager Ray Dalio in his book Principles, believability is a method for evaluating expertise.

The idea goes as follows — when asking people for advice, apply a suitable weight to their recommendations:

- The person must have had at least three successes. This reduces the probability that they are a fluke.

- They must have a credible explanation for their approach when probed. This increases the probability that you'll get useful information out of them.

If an expert passes these two requirements, you may consider them ‘believable’. Dalio then suggests a communication protocol built on top of believability: if you’re talking to someone with higher believability, shut up and ask questions; if you’re talking to someone with equal believability, you are allowed to debate; if you’re talking to someone with lower believability, spend the least amount of time hearing them out, on the off chance they have an objection you haven’t considered before; otherwise, just discount their opinions.

The second requirement is that an expert is more believable if they are exposed to negative outcomes in their domain. This idea is one that I’ve stolen from Nicholas Nassem Taleb’s Skin in the Game — which essentially argues that experts who are exposed to downside risk are more prudent in their judgments and decisions compared to experts who aren’t.

So, for instance, Singaporean diplomats are nearly all ‘realists’ because they can’t afford to get things wrong in their assessments of the world (the city-state is pretty much screwed if they ever piss off a more powerful neighbour … and all their neighbours are more powerful than they are); in America, officials in the state department can afford to hold more ideologically-motivated ideas around foreign policy. This isn’t a personal observation, mind — I have to admit that I am quite influenced by my friends in Singapore’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs; nevertheless, I have always found the Singaporean perspective of world affairs to be more incisive than that of many other countries.

I’ll leave the full argument for this idea to Taleb, but I will say that the rule seems to hold up in my experience. By total coincidence, in the opening of Principles, Dalio tells the story of being shopped around to see the various central banks in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Dalio’s fund had developed models that predicted the financial crisis; the economists who ran the central banks did not. An armchair critic projecting Taleb’s pugnacious personality might argue that Dalio was exposed to downside risk, whereas the average central banker wasn’t. Whether this principle holds true at a universal level is an exercise for the alert reader.

The third level, below advice from people who are both believable and exposed to downside risk, are people who are ‘merely’ believable. Expert opinion is still better than non-expert opinion, and we should seek it out whenever possible. I think this is as good a time as any to discuss one of the biggest objections people have with Dalio’s believability.

When I tell people about Dalio’s believability metric, they often bristle at the idea that one should discount the opinions of lower-believability people. “Isn’t that just ad-hominem?” they say. “An opinion or argument should be evaluated by its own merits, not on how credible the person making it is.”

This is, I think, the most counter-intuitive implication of Dalio’s believability rule. Traditionally, we are taught that good debate should not take into account the person making an argument; any argument that is of the form “Person is X, therefore his argument is wrong” is bad because it commits the ad-hominem fallacy. Instead, a ‘good’ counter-argument should attack either the logical structure of the argument or its premises.

But then consider the common-sense scenario where you’re asking friends for advice. Let’s say that you want some pointers on swimming, and you go to three friends. Which of the following friends would you pay more attention to: Tom, who is a competitive swimmer, Jasmine, who is a casual swimmer, or Ben, who does not know how to swim? It’s likely that you’ll pay special attention to Tom and Jasmine, but ignore (or heavily discount) whatever Ben says.

Credibility counts when it comes to practical matters. Just because Ben makes a convincing and rhetorically-compelling argument doesn’t change the fact that he hasn’t tested it against reality. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying that Ben is certainly mistaken — he could be right, for all we know. But it’s just as likely that he’s wrong, and if you’re like most practitioners, you don’t have a lot of time to test the assertions that he makes. The common-sense approach is to go with whoever seems more credible, along with the assumption that it still might not work for you; we could say here that you’re applying a probability rating to each piece of advice, where the rating is tied to the believability of the person giving said advice.

When I began writing this essay I didn’t expect to defend ad-hominem as a second-order implication of Dalio’s believability. But then I realised: this isn’t about argumentation — this is about figuring out what works. You don’t necessarily have to debate anyone; you can simply apply this rule in your head in place of whatever gut-level intuition you currently use. And it’s probably worth a reminder that you don’t have to make a black-or-white assessment when it comes to low-believability advice. The protocol that Dalio prescribes asks that you ‘do the bare minimum to evaluate what they have to say … on the off-chance that they have an objection you’ve not considered before’. Or, to phrase that in Bayesian terms: keep the objection in mind, but apply a low confidence rating to it.

Why does believability work? I think it works because argumentation alone cannot determine truth. This is a corollary to the observation at the beginning of this essay that ‘rhetoric is powerful’ — and I think some form of this is clear to those of us who have had to live with decisions at an organisational level. Consider: have you ever been in a situation where there were multiple, equally valid, compellingly plausible options — and it isn't clear which option is best? In many organisations, the most effective answer when one has reached this point isn't to debate endlessly; instead, it’s far better to agree to a test that can falsify one argument or the other, and then run it to see which survives reality.

The logical conclusion from “you can't evaluate advice by argument alone” is that you'll have to use a different metric to weight the validity of an aforementioned argument. The best test is a check against reality. The next best test is to look for proxies of checking against reality — such as a track record for acting in a given domain. This is, fundamentally, why believability works — it acts as a proxy for reality, in the form of “has this person actually checked?” And if not, it's probably okay to discount their opinion.

Lower Levels of the Pyramid

Below believability we get to sketchier territory. The fourth level of my proposed hierarchy of evidence is advice from people who have actually tried the advice in question. This isn't as good as “believable expert who has succeeded in domain”, but it's still better than “random shmuck who writes about self-help that he hasn't tried”.

Advice from this level of practitioner is still useful because you may now compare implementation notes with each other. A person who has attempted to put some knowledge into practice is likely to also have some insight into the challenges of implementing aforementioned knowledge. These notes are useful, in the same way that case studies are useful — they provide a record of what has worked, and in what context.

There’s also one added benefit to studying advice from this level of practitioner: you may check against the person's results if you have no time to implement such an intervention yourself. It doesn’t cost you much to circle back to a self-help blogger or person and ping them: “hey, your experiment with deliberate practice — how did it go?” I’ve occasionally found it worthwhile to schedule 15-minute Skype calls with willing practitioners to probe them for the results of their experience.

The last and final rung on my proposed hierarchy is plausible argument. This is the lowest-level form of evidence, because — as I’ve argued before — the persuasiveness of an argument should not affect your judgment of the argument’s actual truth.

Some friends have pointed out to me that the structure of an argument should at least be logically valid — that is, that the argument should be free of argumentative fallacies, and have a propositionally valid argumentation form. If an argument fails even this basic test, surely it cannot be correct?

I think there’s some merit to this view, but I also think that there’s relatively little one can gain from studying the internal consistency of an argument. To state this differently, I think that it is almost always better to run a test for some given advice — if such a cheap test exists! — compared to endlessly ruminating about its potential usefulness.

Luck and Other Confounding Variables

At this point you're probably ready to leap out of your chair to point out: “What’s the use of relying on this hierarchy of evidence? The expert that you are seeking advice from might just have been lucky!”

Yes, and luck is a valid objection! Confounding variables like luck are one of the biggest problems we face when operating at the level of anecdotal evidence. We don’t have the rigour that comes with the scientific method, where we can isolate variables from each other.

(Dealing with luck is also one reason Dalio’s believability standard calls for three successes, to reduce the probability that the practitioner is a fluke.)

But why stop at luck? Luck isn't the only confounding variable when it comes to anecdata, after all. There's also:

- Genetics. The expert could have certain genetic differences that make it easier for them to do what they do.

- Cultural environment. The expert could be giving you advice that only works in their culture — organisational or otherwise.

- Prerequisite sub-skills. ‘The curse of expertise’ is what happens when an expert practitioner forgets what it's like to be a novice, and gives advice that can't work without a necessary set of sub-skills — skills that the expert mastered too long ago to remember.

- Context-specific differences. The expert could be operating in a completely different context — for instance, advice from someone operating in stock picking might not apply cleanly to those running a business.

- External advantages. Reputation, network, and so on.

Let’s say that you are given some advice by a believable person with exposure to downside effects — which is the second highest level of credibility in my proposed hierarchy of practical evidence. You attempt to put the advice to practice, but you find that it doesn’t work. What do you conclude?

The naive view is to conclude that the advice is flawed, the expert is not believable, or that some confounding variable might have gotten in the way. For instance, you might say “oh, that worked for Bill Gates, but it’s never going to work for me — Gates got lucky.”

What is a practitioner to do in the face of so many confounding variables? Should you just throw your hands in the air and say that there’s absolutely no way to know if a given piece of advice is useful? Should you just give up on advice in general?

Well, no, of course not! There are far better moves available to you, and I want to spend the remainder of this essay arguing that this is the case.

One of the ideas that I’ve sort of snuck into this essay is the notion of applying a probability rating to some statement of belief. For instance, in the segment about falsifiability, earlier in the essay, I mentioned that we could take our belief in a hypothesis (with swan colours, I said that perhaps we start with 0.6) and then increase or decrease that belief as we gather more evidence. Some people call this activity ‘Bayesian updating’, and I’d like to suggest that we can adapt this to our practical experimentation.

Here’s a recent example by way of demonstration: a few months back I summarised Cal Newport’s Deep Work, and started systematically applying the ideas from his book to my life. I’ve found that Newport’s method of ‘taking breaks from focus’ to be particularly difficult to implement — I would try it for one or two days, and then regress to where I was before.

I started the experiment with the notion that Newport was believable — after all, he mentioned that he used the techniques in his book to achieve tenure at a relatively young age. My estimation of the technique working for me began at around 0.8.

After putting his technique to the test and failing at getting it to work, I sat back to consider the confounding variables:

- Luck: was Newport lucky? I didn’t think so. Luck has little to do with the applicability of this technique.

- Genetics: could Newport have genetic advantages that allowed him to focus for longer? This is plausible. Thanks to the power of twin studies, we know that there is a genetic basis for self-control — around 60% of the variance if we take this meta-analysis as evidence.

- Prerequisite sub-skills: could Newport have built pre-requisite sub-skills? This is also plausible. Newport has had a long history of developing his ability to focus in his previous life as a postdoc researcher at MIT. There may be certain intermediate practices or habits that I would have to cultivate in order to attempt his technique successfully.

- Context-specific differences: Newport could also benefit from his work environment. He has said that an ability to perform Deep Work is what sets good academics apart from their peers. This might provide him with a motivational tailwind that others might not possess.

- External advantages: I can’t think of any external advantages Newport might have deployed in service of this technique.

It’s important to note here that I am not committing to any one reason. There are too many confounding variables to consider, so I’m not attempting to do more than generate different plausible explanations. These plausible explanations will each have a confidence rating attached to them; as I continue to adapt the technique to my unique circumstances, my intention is to update my probability estimate for each explanation accordingly. These explanations exist as potential hypotheses — I am in essence asking the question: “why isn't this working for me, and what must I change before it does?”

Regardless of my success, I will never know for sure why Newport’s technique works for him and not for me. I will only ever have suspicions … measured by those probability judgments. This is a fairly important point to consider: as a practitioner, I am often only interested in what works for me. Rarely will I be interested in some larger truth like why some technique works for one person but not for another. This is, I think, a point in favour of a personal epistemology: the standards for truth are lower when you’re dealing with effects on a sample size of one.

If this is a form of Bayesian updating, when does the updating occur? The answer is that it occurs during the application. In my attempt to apply Newport’s technique, I’ve gained an important piece of information: I now know that without modification, Newport’s ‘breaks from focus’ advice is unlikely to work for me. I would have to modify his advice pretty substantially. The update is negative — my overall confidence in this particular technique is now down to 0.7.

The path forward is clear: I may attempt to continue experimenting with Newport’s technique — or I may shelve this piece of advice when my confidence dips below … 0.5, say. There are many variations to consider before I hit that level, though. I could attempt to build some easier, self-control sub-skills first. Or I could attempt to meditate to grow my ability to focus. I could clear my workspace of distractions, or attempt to pair Newport’s technique with a pomodoro timer. And even if I fail and shelf Newport’s technique, I could still stumble upon a successful variation by some other practitioner years from now, and decide to take the technique down from my mental shelf to have another go at it.

The point of this example is to demonstrate that confounding variables are a normal thing we have to grapple with as practitioners. We don’t have the luxury of the scientific method, or the clarity of more rigorous forms of knowledge. We have only our hunches, which we update through trial and error. But even hunches, properly calibrated, can be useful.

Fin

I have presented an epistemology that has guided my practice for the past seven years or so. I’ve found it personally useful, and I believe much of it is common sense made explicit. But I also know that this epistemology isn’t at all finished; it is merely the first time that I’ve attempted to articulate it in a single essay.

To summarise:

- Let reality be the teacher. This applies for both scientific knowledge and anecdotal evidence.

- When spelunking in the research literature, keep in mind that science is interested in what is true, not necessarily what is useful to you.

- When evaluating anecdata, weight advice according to a hierarchy of practical evidence.

- When testing advice against reality, use some form of Bayesian updating while iterating, in order to filter out the confounding variables that are inherent in any case study.

If I were to compress this framework for putting mental models to practice into a single motivating statement, I would say that the entire framework can be reconstructed through a personal pursuit of the truth — and that in the context of practice, this truth takes the form of the question: “What can I do to make me better? What is it that works for me?”

Now perhaps you’ve noticed the meta aspect of this epistemology.

What happens if we apply the standard of truth that I’ve developed in this essay to the very series within which I’ve chosen to publish it in?

The answer is this: my framework should not be very convincing to you. I am not believable in any of the domains that I currently practice in: I have built two successful organisations of under 50 people each; I’ve had only one business success. I am at least a decade away from becoming believable at the level of success that Dalio demands.

What I can promise you, however, is that everything in this series — with one exception* — has been tested in personal practice. I currently apply this epistemology of practice to my own life. I spent a few ‘misguided’ years on epistemic rationality training, of the sorts recommended by LessWrong. I still sometimes feel the itch to do rational choice analysis — even though I know that such analysis works best in irregular domains. And I have spent the last three years in the pursuit of tacit mental models of expertise.

(*The only exception is the critical decision method, covered in Part 5. As of writing, I've only had two months of experience with the method.)

I’ve spent a great deal of time on the rhetoric of this series. I’ve used narrative to propel the reader through certain segments where I’ve had to tackle abstract ideas, and I have attempted to summarise the least controversial, most established findings of the judgment and decision making literature from which rationality research sits upon. But you should not believe a single word that I have written. In fact, I would go further and suggest that your degree of belief should be informed mostly by that which you have tested against reality. In Bruce Lee’s words: absorb what is useful, discard what is useless and add what is specifically your own. In Bayesian terms: everything I say should be regarded as an assertion with a confidence rating of far less than 1.

Perhaps this is taking it too far. But then again, perhaps Hume had a point. There is ultimately no truth except that which you uncover for yourself.

I hope you’ve found this series useful.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→