Technique Goal: We need a reasonable framework for evaluating non-scientific advice. As a practitioner, you often have to seek advice from others. How do you evaluate the credibility of the advice you're given? This technique proposes a hierarchy of practical evidence.

Technique Summary: When you are a practitioner, you often cannot rely on scientific evidence for one course of action or another. This is because a) no such evidence might exist for your specific situation, b) statistical predictors work for populations, but do not predict well for the individual, and c) the ultimate test is if it works for you, because of individual variation, and conflating factors like luck in the life of the person you are seeking advice from.

Therefore, you need a framework for evaluating advice given to you by practitioners.

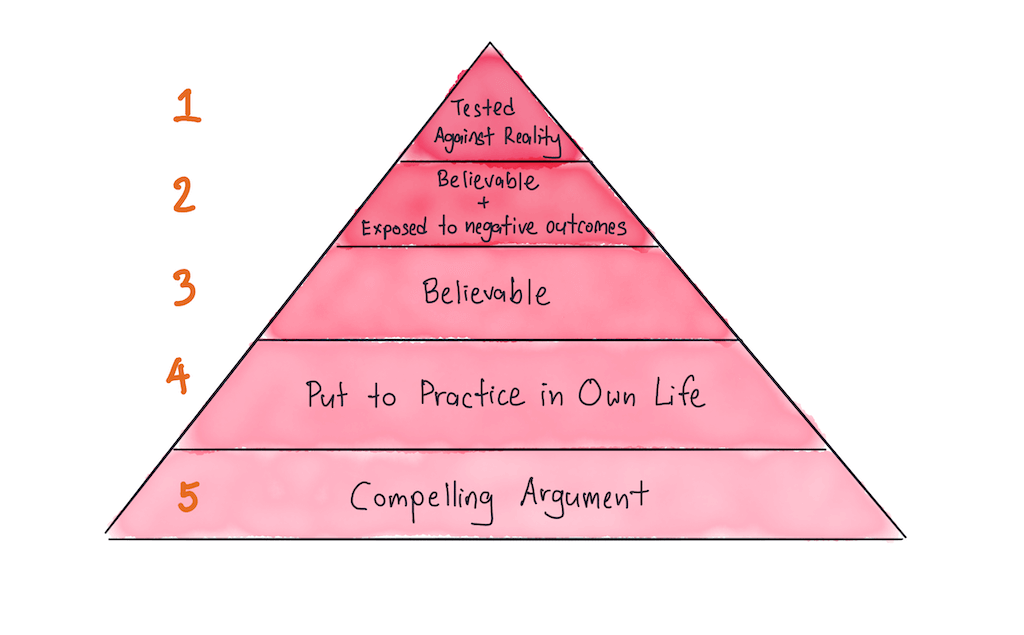

Commoncog’s proposed hierarchy follows:

- Tested against reality. This is the highest level of practical evidence. You have tested the technique in your own life, and have found that it works for you.

- Believable & exposed to negative outcomes. The second level, below ‘tested against reality’. The person giving you advice is believable (definition here) and is exposed to negative outcomes in her field. Exposure to downside risk is also called ‘skin in the game’ by author Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Experts who have such exposure are more credible, because if they are wrong, they lose materially (in terms of money, career prospects, or significantly important life outcomes). This incentivises them to get their opinions right.

- Believable. One level below this are expert practitioners who are ‘merely’ believable. The definition of believability is ‘has at least three successes in the relevant field, and has a credible approach when probed’. I've done a full-writeup of this technique here.

- Put to practice in own life. People who have applied the technique that they are giving you advice about is the next level of credibility in this hierarchy. This is because they have at least attempted to test the technique against reality. You may thus learn nuances of said technique from their experiences. Corollary: beware people who recommend techniques they've never tried, distrust advice from people who read but do not practice.

- Compelling argument. This is the lowest acceptable level of the hierarchy. Advice should be considered if the advice is internally consistent and constructed with no glaring logical flaws. This is the lowest possible level because it is easy to say things that are insightful — and in today's attention economy, there are lots of people out there who have optimised for insight in the hopes of capturing attention. This does not make said thing effective or true.

Origin: Part 6 of Commoncog’s Framework for Putting Mental Models to Practice, titled: A Personal Epistemology of Practice.

There are several second-order implications from this idea.

- Ad-hominem is legitimate when it comes to evaluating practical advice. This is covered more fully in the original piece (relevant section linked).

- There are situations where changing environments render credible advice from believable people mistaken. But in order to disregard such advice, you should have a credible argument for why you believe expertise can be discounted.

- Effective advice often sounds insightful, but advice that sounds insightful is not always effective. It is easy to conflate the two. It is easier still to do so when one is on Twitter.

- Due to confounding factors (such as genetics, privilege, luck, and external circumstances), believable advice may still be inapplicable. The practitioner's art is to investigate the essence of the technique while adapting it from the unique circumstances of its original application.

There are likely more second-order implications. We encourage you to come up with them for yourself.

Originally published , last updated .