Imagine that you have a job interview coming up for a startup. Unlike interviewing for larger, more prominent companies, the vast majority of startups aren’t very famous, and you’re not likely to know anyone working in that particular company. So how do you figure out if working at this startup will fit into your career goals?

The quick and dirty answer is that it’s very difficult to tell — pretty much any job interview is a highly compressed process that leaves out valuable information you’ll need in order to answer that question. But it turns out that there’s a related question that’s easier to answer, that’s nearly as useful as our first question above.

The question is this: “how do you disqualify bad companies that won’t help you towards your career goals?”

This question is easier to answer because you are much better at identifying specific bad traits that you may then test for. If a company you’re interviewing with fails your set of tests, then you may quickly disqualify that company. Conversely, if a company passes all your tests, this doesn’t mean that the company is good for your career goals — it may or may not be; there may well be negative attributes that you’ve not thought to test for — but at the very least, you’ve vetted a company according to a known set of possible downsides.

Regardless of whether you’re testing for positive or negative traits, you’ll need a way for getting information effectively out of your interviewers. This is where head-fake questions can help.

Head-Fake Questions

A ‘head-fake question’ is my name for a technique that has helped me a ton over the past few years. A few friends have told me that my formulation has been useful to them, and so I thought it would be a good idea to write it down in an essay for future use.

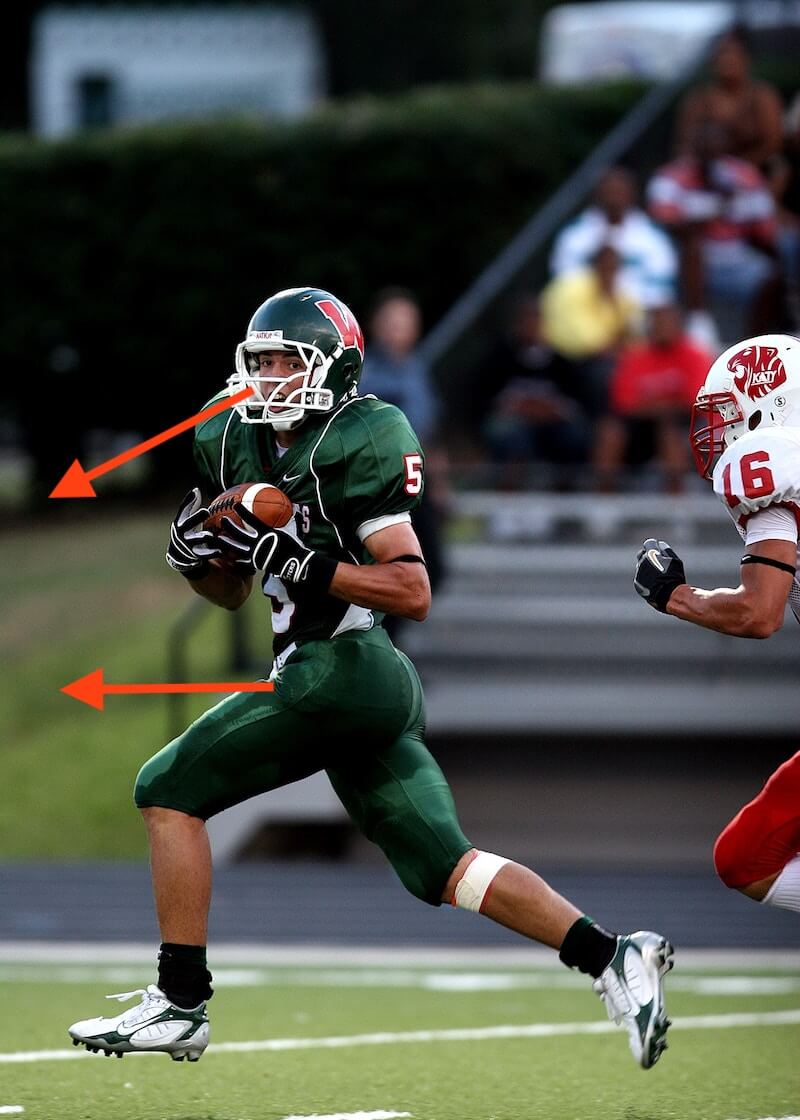

In American football, a ‘head fake’ is a technique where a football player turns their head to look in one direction but runs in another direction instead. A head-fake question, then, is a question that purports to ask about one thing, but is in reality asking about something else.

(Credit where this is due: I got the idea from Randy Pausch’s Last Lecture, where he uses ‘head fake’ as a lens through which to see many life activities. The concept is broadly useful.)

Here’s a concrete example. When interviewing with a sales-driven B2B product company, one of my most important vetting questions is about the tension between product and sales. My question usually takes on the form of: “In my experience, some clients demand extensive customisations. How do you balance client customisations that you need to do to close sales deals, against spending engineering time on features that are more generally useful for the rest of your users?”

My interviewer will usually see this as a question about the company’s practices or processes. But what I’m actually trying to find out is the amount of power the product organisation has in relation to the sales organisation. A healthy tension between the two — expressed in a give-or-take relationship — is a good sign that a lot of things are going right in the company. Conversely, a company where product consistently overrules sales considerations, or where product is overruled by excessive client customisations in the service of closing is a highly dysfunctional company to work in.

Now don’t get me wrong: a dysfunctional company may well be a successful company. But the specific type of dysfunction matters for you when you plan your career. A company that prioritises product over sales may die against its more aggressive competition; a company that prioritises sales over product strategy will be an incredibly limiting place to work in as a member of the product organisation. As a software engineer, the former scenario might find you laid off; the latter scenario would cause your growth to be severely limited as the company whiplashes between servicing very different clients.

In any case, the range of answers that an interviewer gives me in response to my question will tell me a lot about the startup in question:

- If the interviewer asks “what tension?” or betrays a general cluelessness about the existence of this tension, this startup is immediately disqualified. Recognising this tension is the bare minimum I expect of any leader in a B2B, sales-driven product startup. The tension should also be obvious to everyone in the engineering organisation.

- Far more common is an interviewer who repeatedly gives a vague or high-level answer. This is also a disqualification: either the interviewer hasn’t thought enough about the topic, doesn’t know about the tension, or there’s something bad going on that they’re trying to hide.

- The best sort of answer is one with concrete details, or illustrated with a few specific examples. This then lets you dig further:

- If the interviewer is from the product or engineering side of the company and they display any negative body language while I’m asking the question, I pick up on it and start asking increasingly detailed questions. Is my interviewer personally disgusted with the amount of power sales holds over engineering? Are they overly biased against sales — and if so, does this signal a cultural problem? Does the company recognise that it’s a problem, and are trying to fix it? If so, how are they fixing it? What’s the relationship like between the head of product and the head of sales? I will then follow up with similar questions to other members of the company in the course of the interview process, in order to triangulate on the truth.

- An equally telling follow-up question is about how the sales incentives are structured for the sales org, and who owns the customer relationship after the sale has closed. Both questions illuminate the degree with which the company has thought about this tension and built it into its organisational design.

- In most cases, what I’m looking for is a thoughtful approach to this tension. The tension does not have to be solved — in many cases, it can’t be solved — but company leadership must recognise that managing the tension between product and sales is key for business success.

Head-fake questions work because people are often really good at stretching the truth when they represent the company in a job interview setting or public-facing environment. Unless things are horribly toxic in the company, most interviewers or company reps won’t want to talk bad about their employer.

With a head-fake question, however, an interviewer cannot lie to you, because they don’t know what you’re really asking for.

Breaking It Down

All good head-fake questions contain a small number of similar properties:

- The question is about concrete examples or specific details.

- The question is open ended, and is expressed as either a ‘what’ or ‘how’ question.

- The question is drawn from your experiences in a similar company, industry, or problem domain.

Let’s go through each of these properties in order.

First, a head-fake question has to be about concrete examples and specific events, because it’s difficult to lie when you’re discussing concrete details. It’s often a warning sign if the person you’re talking to repeatedly resists giving concrete details and specific examples, and instead backs out to broad platitudes. Your test should disqualify those who resist specificity.

Second, ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions are open-ended and do exactly what they say on the tin: they broaden the conversation and expose you to information you wouldn’t have known to ask about otherwise. Asking a ‘yes/no’ question, on the other hand, narrows down the discussion. It’s often not a good idea to ask direct, ‘yes/no’ questions like “does your sales organisation force you to create client customisations against your will?” — this frames the query according to your preconceived notions of the organisation. In contrast, asking “what happens when sales asks you to do extensive client customisation for an important client?” opens up the discussion by letting the other person take control of the conversation according to their knowledge of the company. This increases the chance you’ll come across new and important information.

Third, the best head-fake questions demand knowledge about the inner workings of an industry. It’s no accident that my head-fake questions are all about startups — unlike many of my friends who got into large tech companies early in their careers, my career path required me to join existing startups in the pursuit of skills that could help me in my career goal of going into business for myself. My head-fake questions stem from my experience of dysfunctional organisations and painful startup failures.

An important implication of this idea is that you can’t know what questions to ask if you have no experience of the field. If I were a software engineer who wanted to move into finance, I would not know how to evaluate between the dizzying number of prop trading firms that might be recruiting for programmers. I can’t ask them for details because they’re likely to stretch the truth; at any rate, I don’t know what organisational dynamics I’m ok with, or what organisational dynamics might get in the way of my career goals.

I’ve often argued that the true benefit of university internships for students are that they get to learn the best (head-fake) questions to ask during their eventual careers. But this remains true for those of us who are already knee-deep in our careers: every job you’re in is an opportunity to broaden the set of head-fake questions you may use for the next company you move to.

If you find a dynamic you don’t like in your current company, it pays to come up a question that would reveal that dynamic in other companies, so that you may identify and avoid jobs at similar organisations in the future.

After all, the cost of not being thoughtful about your career moves is fairly large: each move lasts a few years, and the opportunity cost of moving to a bad company is to essentially give up on skills and career capital you may have gained in a better role. In practice, however, I’ve found that thinking about opportunity cost is a far less useful way to think about my career moves — a far simpler, and more useful ability is the ability to avoid grossly dysfunctional organisations.

You can’t know if a company is the best move for you in advance; but with a little bit of experience and a little bit of thought, you can almost certainly tell if it’s bad before you jump to join it.

Bonus: here's a Twitter thread where Jensen Harris explains four general head-fake questions he uses when joining a startup.

Get the Action Sheet

Download the actionable summary for Head Fake Questions here →

Originally published , last updated .