One of the things I was trying to do with my series on Chinese businessmen was to describe an approach to doing business that isn’t rooted in startup culture.

Doing a startup is now a hot, aspirational, sexy goal for a sizeable percentage of my friends. It was far less sexy back when I was an 18 year old, reading Paul Graham essays on my bed when I should have been studying. I know people today who think that starting a company is their way out of the corporate rat race. And the place they look to for inspiration? Silicon Valley startup culture.

But here’s the catch: having lived, breathed and optimised for startups for the better part of a decade, I no longer think Silicon Valley culture makes sense for a large swath of people. I’m not even sure startup culture makes sense in Asia. Instead, I currently believe that the startup approach isn’t ideal for many industries, and that it doesn’t work for most businesses.

Granted, this isn't a particular novel observation; anyone who's had any experience running a conventional business would know that received SV wisdom is severely limited. But I do think that it's worth it to wade into the weeds to find the limits of startup wisdom, in case anyone thinks its a good idea to gain a career moat by going into business for themselves.

Optimising VC Outcomes

Pretty much everything I say here can be best understood through the lens of “startup wisdom is about optimising venture capital (VC) outcomes, so take everything you read about startups with the understanding that it's not about optimising outcomes for you.”

Here's a concrete example: in my last post, I talked about something I called the SME loop, which was my name for a ceiling you'll hit if you attempted to grow a small-to-medium enterprise to a large one. This ceiling is so universal, in fact, that I posited that the SME loop was a fundamental law of business.

Conventional startup wisdom has nothing to say about the SME loop, because growing a business to break out of the SME loop takes at least a decade of work. VCs can't benefit from a business that takes that long to grow large; the vast majority of VC funds are required to return their investments within a 10 year period. That means that most VCs will want their companies to grow rapidly enough to get acquired, or go public, before that 10 year deadline.

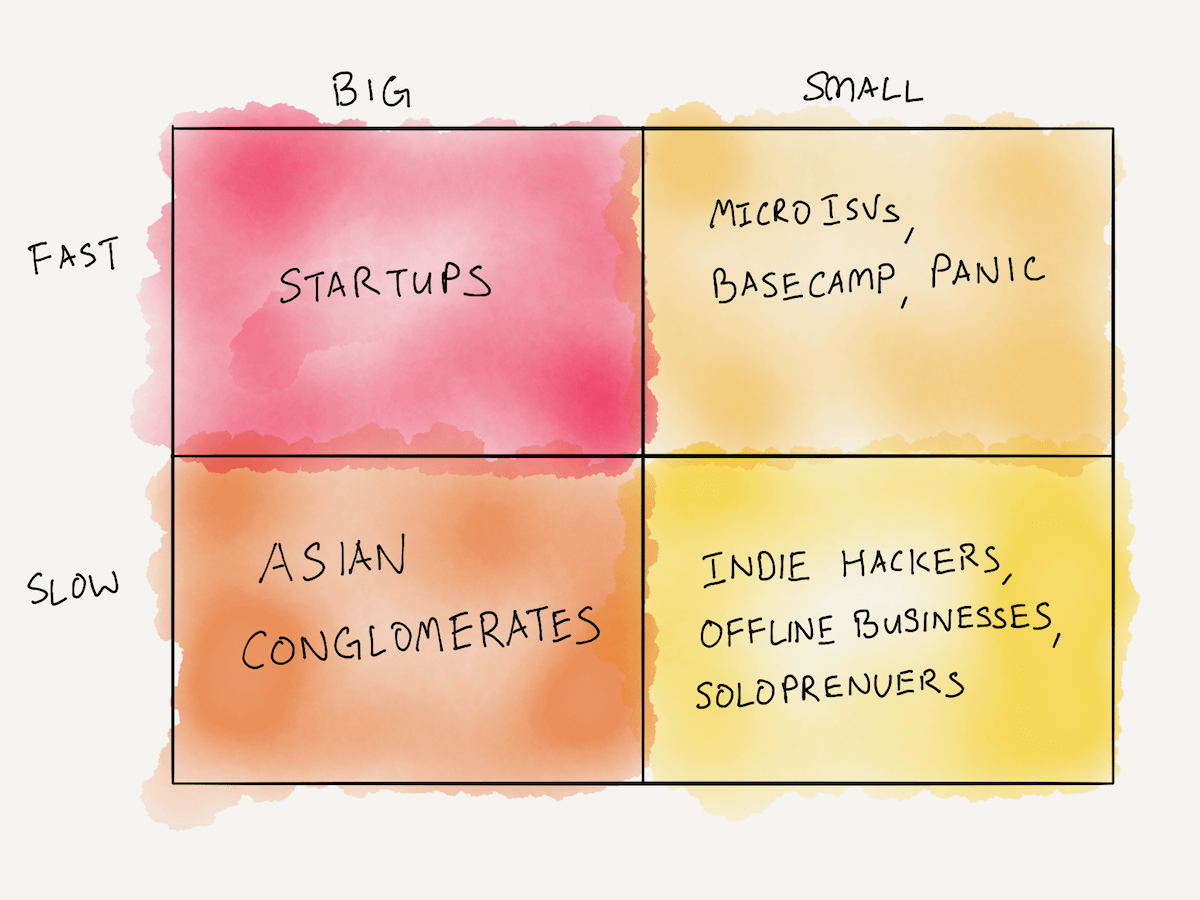

It also means that no VC will ever be able to invest in or benefit from the value created by billion dollar Asian conglomerates like Ng Teng Fong’s Far East Organisation, or Robert Kuok’s Wilmar International — business empires that took over four decades to build. These incredibly valuable companies take far too long to return capital for a typical VC fund, and so startup culture — which is built around VC outcomes — ignores these companies as viable paths for success.

Or, to put it more crudely: the canon of startup advice literally pretends these companies do not exist.

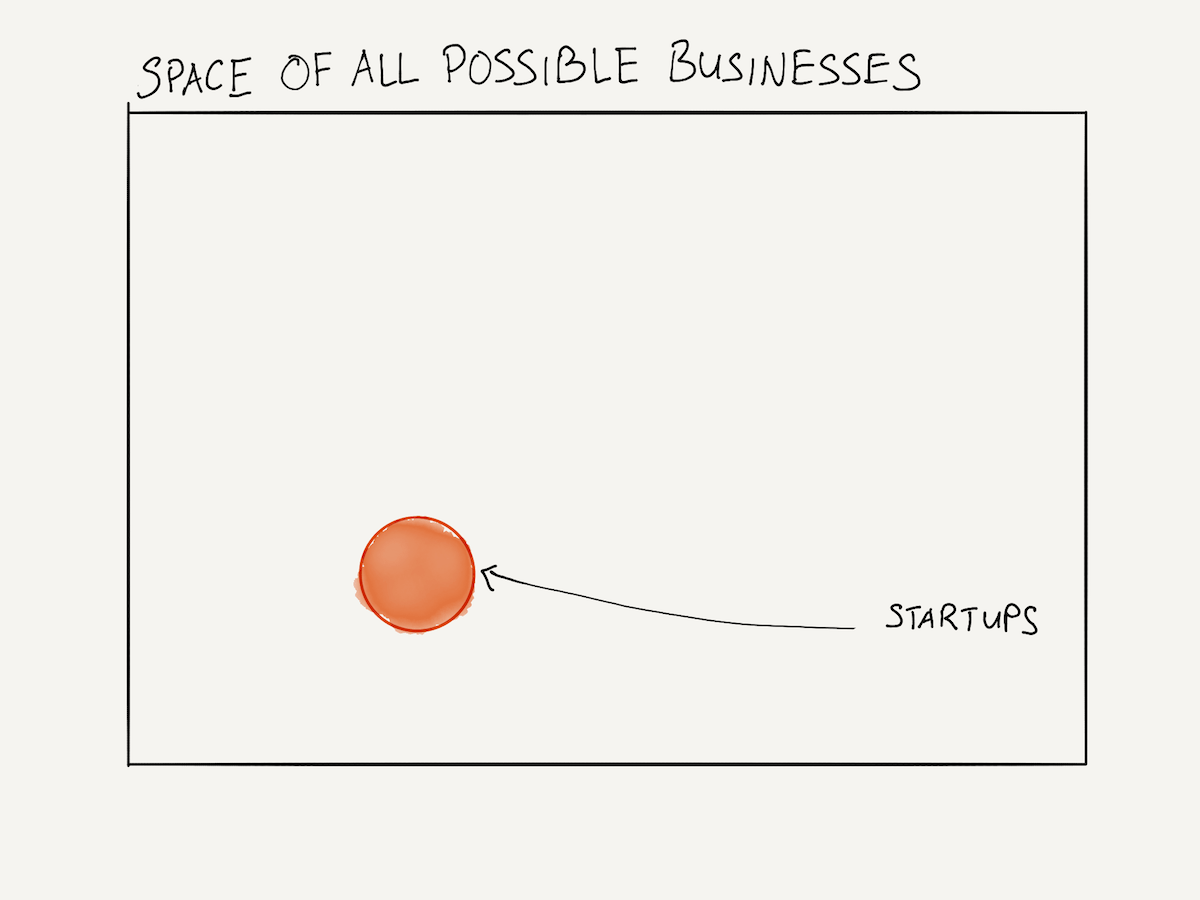

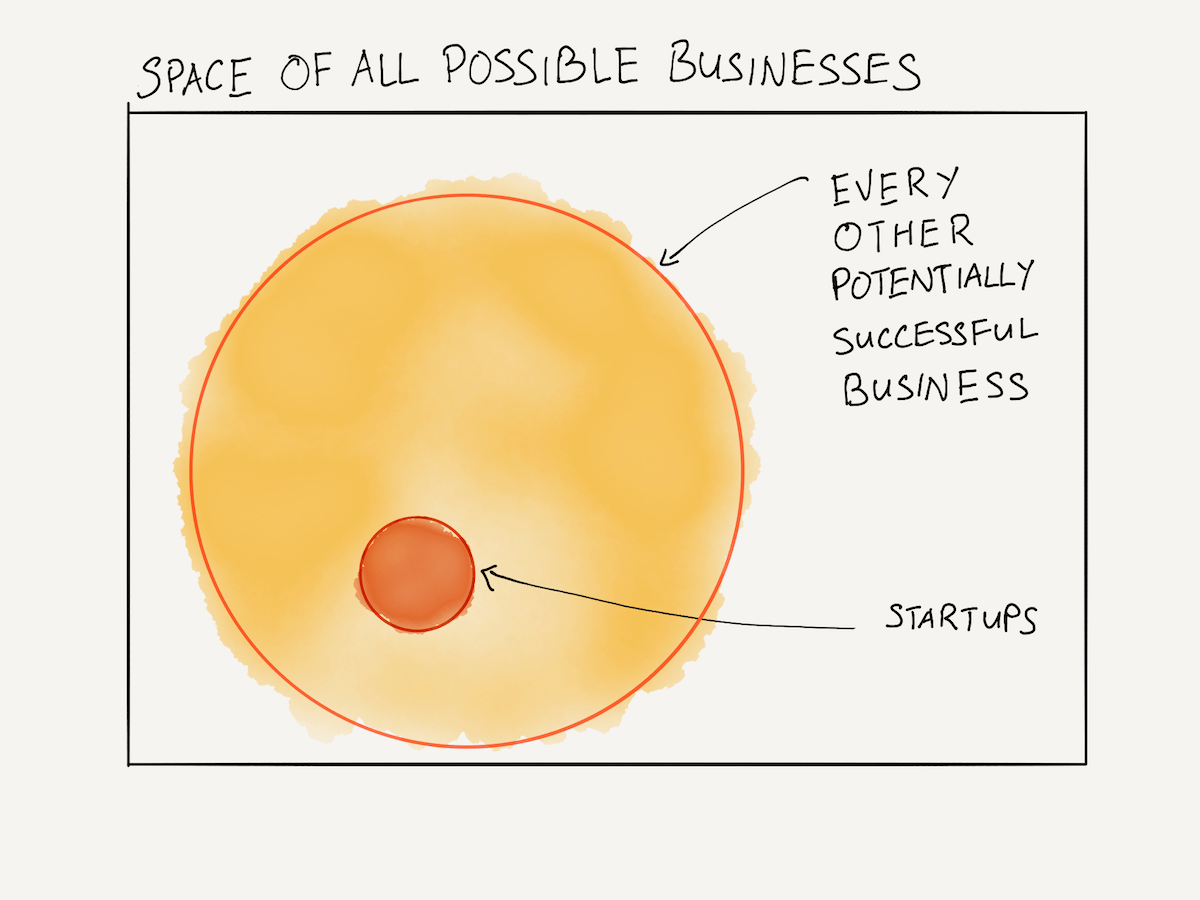

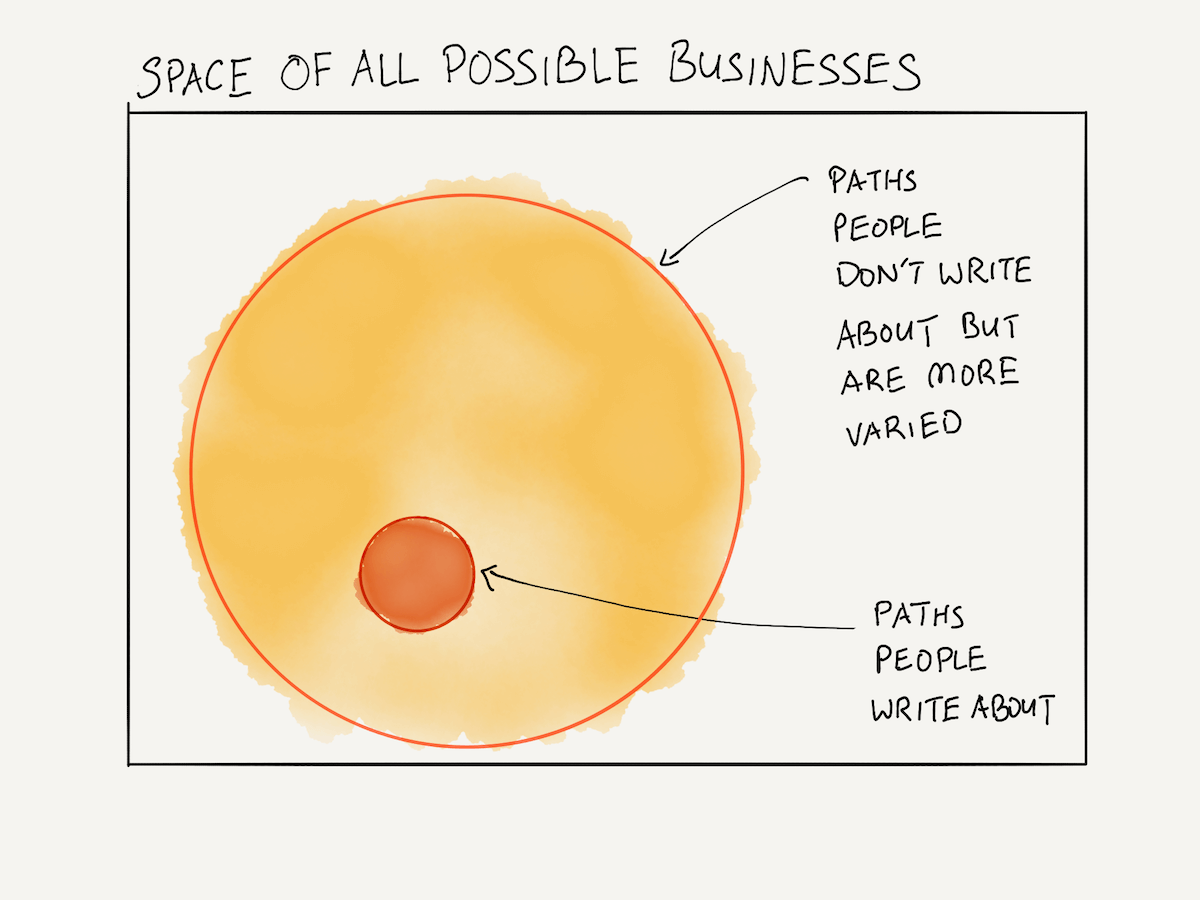

This matters to you if you are an individual entrepreneur, because if you only draw lessons from startup culture, you are prematurely and artificially limiting your paths to success. To use a crude illustration, startup culture gives you a set of recommendations that looks like this:

But the reality of business is that the set of possible paths to business success looks like this:

What’s the difference between the startup set and the superset? The answer is time.

Every venture-funded business is in a race against time to grow big and valuable. Normal businesses are not. The false dichotomy that startup culture makes is to imply that the only way to bigness is through bone-crushing speed. This ignores the many Asian conglomerates that were built over two to three decades of consistent execution. It also ignores the South East Asian monopolies that were built by multiple generations of Chinese business families.

In truth, this need for speed exists because startup VCs need to make a return within a certain time period. It also exists because the companies that make the most returns for VCs are companies that are first to win in a winner-takes-all market. Think Google, or Facebook — companies that are so large and powerful they crush virtually all their direct competition after gaining the upper hand.

Startup investors know this, and so they encourage a bunch of counter-intuitive behaviours. For instance, VCs encourage startups to spend money excessively — anything, really, to gain an edge against the competition. When the goal is to win a monopoly in a winner-takes-all market, financial irresponsibility makes sense.

But this goes further: in fact, everything in conventional startup wisdom may be understood through the lens of making a return for investors within a 10 year time period:

- Don’t start a company without a cofounder. (It’s very stressful to grow a valuable company under 10 years).

- Pick a large and growing market that is overlooked. (It’s easier to grow a valuable company under 10 years when a market is growing but overlooked).

- When taking on investment from VCs, play to their fear of missing out. (VCs need home runs to remain solvent).

- Iterate on your product until you find product-market fit — and you’ll know you’ve found product-market fit when you experience hockey-stick growth. (Hockey-stick growth is how you grow a valuable company under 10 years).

- Move fast and break things. (Growth above all).

- Don’t worry about bad management at the beginning. (Growth above all).

- Do whatever is necessary to reach the next level of growth. (Growth above all).

- Don’t sell out early when you might grow even bigger and win. (VCs win when one company in their portfolio wins big. So it’s probably better to maximise the upside of each bet they make).

The upshot of all of this is that startups are often a crapshoot. The exhortation to grow at all costs lead to scorched earth practices: you either grow big to become a winner in a large and valuable market … or you die. The ones that don’t win and don’t die live an uncomfortable existence: their investors pressure them to get acqui-hired as a means of recouping some of their investment, or write them off as a bad deal and ignore their calls for help.

This is, I hope, obvious to anyone who’s spent any amount of time watching and thinking about startups.

Removing the Deadline

Something interesting happens when you remove the artificial constraints of venture capital. Suddenly, the practices that Silicon Valley preaches as necessary to business fades into irrelevance. When you’re not under pressure to build a large and valuable company in a short amount of time, you have way more options available to you.

These options are wonderfully varied. You may choose to build a profitable business that supports your lifestyle. You may choose to build a profitable business that forms the basis of your business empire — and then strategically take on investment or joint partnerships for your subsidiaries over the course of a few decades (Robert Kuok). You may choose to build and then sell a series of small, profitable internet businesses, eventually parlaying your skills and capital into a go-big-or-go-home company (Rob Walling). You may choose to build a secondary source of income while you pursue conventional employment (Endcrawl). You may choose to take on investment only after you’ve gained enough experience building your position in a market (DS3). Or you may choose to become a digital nomad (Jon Yongfook).

The truth is that there are an infinite number of ways to build a profitable, rewarding business, and to adapt that business to your personal goals. But because the set of paths are so varied, and because nobody stands to make a fortune from your taking them, nobody writes about these paths.

The path gets the most attention is the path of the startup. And the constraints on doing one are so tight that Silicon Valley often says that there’s “only one way to do a startup”.

I’m not arguing that you shouldn’t do a startup. Startups are expected value calculations where the probability of success is low but the payout is high. If you win, you really do win big.

What I’m arguing instead is that startup advice really only applies to a subset of the space of possible businesses you might do. Don’t think that startup advice is the be-all and end-all of business advice. It isn’t; it’s merely a tiny segment you should feel free to ignore.

Originally published , last updated .