Case

Amazon Prime - Burn to Grow

Amazon’s growth story hit an unexpected snag in Q3 of 2004. Its online retail store was still growing, but at a slower pace compared to Q3 of the previous year. As an example, the year-over-year growth of its largest product segment, US Media (books, music, video) went from 15% to 12% growth. Not a huge slowdown, but this was a company that had set its sights on becoming an ‘everything store’. By comparison, Best Buy posted an annual sales growth rate of 17% that year. Furthermore, the shift from offline to online commerce was accelerating. This meant that Amazon could lose its head start amidst online retail’s growth if the trend continued.

By now, Amazon knew that their model worked. The company managed to post profits in Q4 of 2001, their first ever quarterly profit. Two years later, in 2003, they delivered their first ever profitable year. They had largely erased the fears of insolvency first spearheaded by a Lehman Brothers analyst in 2000.

But Bezos was dissatisfied. In mid-October 2004, he sent out an email ordering several senior Amazon executives to launch a shipping membership program. He wrote:

We should not be satisfied with the growth of our retail business. This is a house-on-fire issue and we need to dramatically improve the customer experience around shipping. We need a shipping membership program. Let’s build and launch it by the end of the year.

The company knew that their customers cared about three main things — price, selection, and convenience. Weekly reviews held by senior leaders examined the prices, selection and availability of Amazon’s products. Prices were kept low, selection kept going up, but convenience was slow to improve.

It’s easy to look back today and ask “how inconvenient was online shopping, really?” But it’s important to remember that 2004 was a very different time. Most customers — even some of Amazon’s best — shopped online only a few times a year. And Amazon’s leaders knew that some of their customers, particularly those who required select items urgently, were willing to drive to the nearest store in order to get their products. This was not a consumer behaviour that worked for Amazon.

Hence Bezos’s focus on shipping.

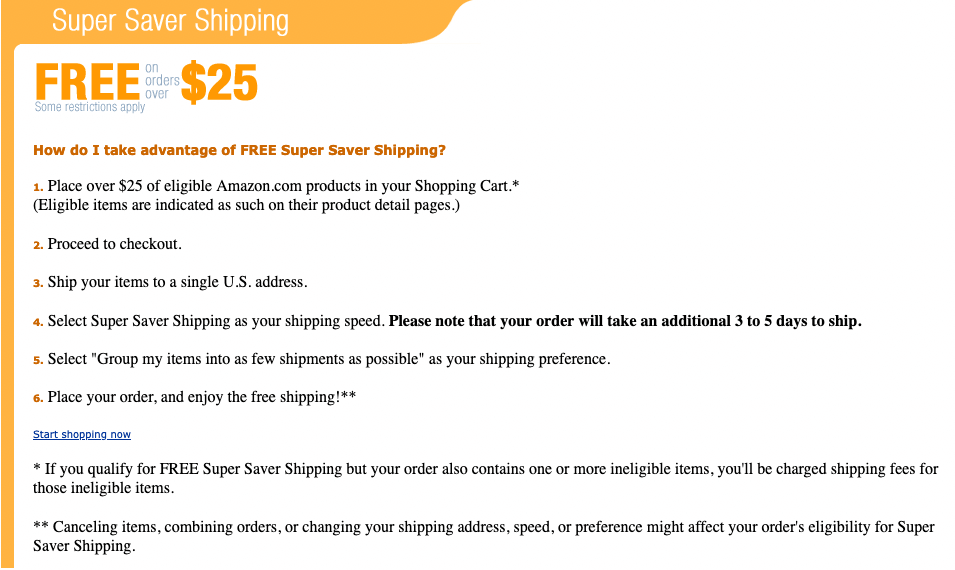

Super Saver Shipping, launched in 2002, allowed customers to get free shipping with a minimum order of US$99 on qualifying products (normal-sized products that Amazon sold itself). The minimum order size was reduced to US$49 and then US$25 over the next few months, but the free shipping was slow. Amazon would hold back ordered items in the fulfilment centre for three to five days and group orders together before shipping it out through a cost-efficient ground delivery service — by the time it arrived, the customer would have waited eight to ten business days. Thus, customers had a choice of getting it delivered “free and slow” or “fast and expensive”, going against Amazon’s stated leadership principle of ‘Insist on the Highest Standards’.

Sourced from Web Archive of Amazon.com on January 12, 2005.

So the question became, was it possible for Amazon to offer free and fast delivery? In early 2004, Bezos considered offering it on pricier items like TVs and jewellery — their higher gross profit would be enough to cover free and fast shipping. But it was later scrapped by category managers because the implementation would be too difficult with their messy promotions and shipping software systems. There also wasn’t a large enough payback to justify the change.

Bezos continued to suggest other ideas every few weeks or so in 2004. He emailed ideas about increasing the shipping speed of Super Saver Shipping or about shipping all jewellery items for free. Before this, Amazon even considered rebates and points-based loyalty programs, like the ones airline companies had. But that idea was soon discarded. The business model of an airline differed from a retail company — airlines could give away unsold seats at no additional cost for their loyalty programs because an unsold seat had no value once the plane took off. But in retail, giving away a physical product or shipping fee always carried a cost.

Around the same time as Bezos’s mid-October email, Amazon engineer Charlie Ward made a proposal before going on vacation (it’s unclear whether Bezos knew about Ward’s idea before or after he sent out his email). If Super Saver Shipping catered to price-conscious customers who were not time sensitive, why not create a service for the opposite type of customer? That is: a speedy shipping club for consumers who were time sensitive and who weren’t price conscious.

When Ward returned from vacation, he was transferred over to the team in charge of launching that membership plan, code-named Futurama. Ward was a software engineer for Amazon’s ordering system, not a business person tasked with solving the growth rate problem. But it didn’t matter. Ward’s idea improved customer satisfaction, and it was in line with Amazon’s ethos to insist that everyone be empowered to think up new ways of delighting customers.

During the development of Prime, there was a surprising lack of data-driven decision making at an otherwise supremely data-driven company. There was no financial modelling to calculate the optimal price point for Prime, for instance. But this was also because no data existed on how customers might change their purchasing habits after joining. Instead, Bezos decided on an annual fee of $79 because he believed it would be large enough to matter to customers, but small enough that they would still be willing to try it out.

The Futurama team had their own doubts about Prime. One of the engineers on the team emailed Greg Greeley, VP of Worldwide Media at the time, to ask:

Greg, we’re working so hard on this project and I look at it and as a [shareholder] I’m really scared. I think it’s going to take down the company (emphasis added). Are you sure the math works on this program?

The concerns were real. For example, if someone ordered a $3 toothbrush via Prime’s two-day delivery, there would be no way for Amazon to make money from that. On the other end, people who ordered heavy, bulky items via Prime would compress margins. In the end, Amazon addressed this by creating the add-on program. It made low-priced-items purchasable via Prime only if you bunched it with the order of a higher-priced-item. And for the heavy items, they would come up with ‘Prime standard’, which was free standard shipping, instead of free two-day shipping.

During Prime’s development, many on the team had already voiced these concerns. They worried about how much money Prime would cost the company. For example, the typical cost of delivery via land was $1.50 a package in 2006. By air, it would be $15. But Bezos held firm. The time to debate was over; the team was expected to disagree and commit.

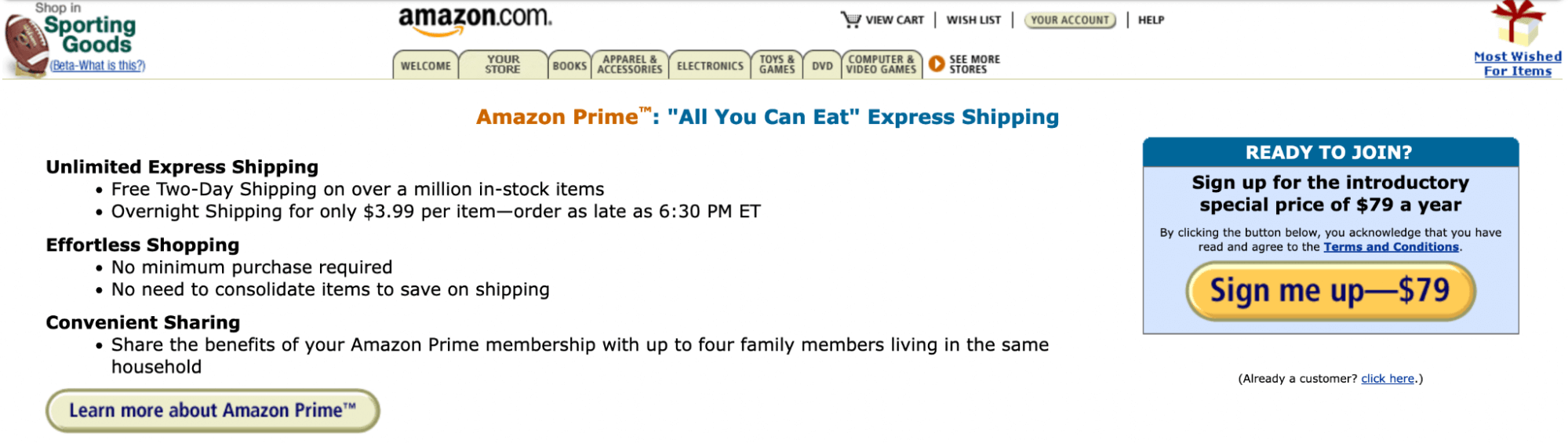

Prime launched on February 2, 2005. In the accompanying press release, Bezos said:

Amazon Prime is ‘all-you-can-eat’ express shipping. Though expensive for the Company in the short-term, it’s a significant benefit and more convenient for customers. With Amazon Prime, there’s no minimum purchase to think about, and no consolidating orders—two-day shipping becomes an everyday experience rather than an occasional indulgence.

Sourced from Web Archive of Amazon.com on February 10, 2005.

Soon after launch, Bezos kept a close eye on Prime sign-ups and intervened to keep the promotional banner on top of Amazon’s homepage. Amazon’s leadership team kept a close eye on three metrics in particular: number of orders per year, number of items per order, and number of items per year.

Andrea Leigh, a former Amazon Canada leader for Prime recalled that initial growth was slow, and that Prime didn’t overtake Super Saver Shipping immediately. In fact, the early data rang alarm bells. Prime’s first subscribers were hardcore Amazon customers who paid extra for two-day shipping before Prime’s existence. In other words, they had signed up for Prime because they could now get it for less!

In the short term, this meant Amazon would have to deal with lower shipping revenue, which reduced their already razor-thin profit margins. But Bezos didn’t panic. He was convinced that Prime, like Super Saver Shipping before it, would change customers’ behaviour and motivate them to place more and bigger orders. If this happened, it would increase Amazon’s volume, giving them the leverage to negotiate for lower prices from its shipping partners and vendors. At the same time, the supply-chain teams worked to make inventory, packaging, and delivery more efficient, lowering costs.

In the short term, Prime developed into an exceptional growth engine, even as it burned through more dollars. Bezos’s predicted consumer behaviour change would come slowly. A year later, though, Prime led to an unexpected opportunity.

In 2006, Amazon launched Fulfilment by Amazon (FBA) — a program that let third party merchants store their products with Amazon for a fee, and in return, qualify for Prime two-day shipping. By that point in time, Prime two-day shipping was such a compelling value proposition that merchants wanted to get in on it. Operations director Berg Wegner said:

That is when it really hit home, we had built such a good service that people [merchants] were willing to pay us to use it.

By 2007, two years after launch, internal data finally showed that on average, customers who joined Prime doubled their spending on the site. Bezos’s predicted consumer behaviour change had finally turned up. And perhaps it shouldn’t be so surprising that it took this long — if your customers shopped online only a few times a year, it would take a few years before the overall trend became clear.

In 2011, Amazon increased the value proposition of Prime by adding Prime Video, their streaming service, for no extra cost. They followed it up with Prime Music and Prime Now (a two-hour delivery service) in 2014. And in 2019, they made two-day shipping obsolete with a new standard of one-day shipping. That year, Prime had grown to over 100 million members. In 2021, there are now more than 200 million Prime members globally.

Questions

Compare this case with a previous case you've read. What is similar? What is different?

Does this remind you of a similar case? If so, what is different there?

If you have any thoughts, feel free to comment in the member's forum.

Sources

Working Backwards by Colin Bryar and Bill Carr. Published in 2021.

The Everything Store by Brad Stone. Published in 2013.

https://www.vox.com/recode/2019/5/3/18511544/amazon-prime-oral-history-jeff-bezos-one-day-shipping

https://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/28/business/technology-amazon-reports-first-full-year-profit.html

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1018724/000119312505017451/dex991.htm