Case

Hershey’s — The Hunt For Milk Chocolate

In March 1900, Milton Hershey sold his caramel factory — the jewel of his first candy empire — for a million dollars. He was 43 years old. The Lancaster New Era wrote: “Hershey Sells Out to Rival; Move Stuns Industry”. The Lancaster Intelligencer read: “Hershey Gives Up Empire for $1 Million.” The tone of all the newspaper reports were incredulous: Hershey’s decision made no sense. By the late 1890s, Hershey was mostly known as the owner of the Lancaster Caramel Co. He had a thriving business, plenty of money, a beautiful wife, a lovely home, and the respect of everyone who knew him. And to put the move into perspective, his business success was extremely hard-won: Hershey had failed at multiple earlier ventures; at one point he was forced to hire himself out as a day labourer to pay off his debts.

Hershey appears to have had a plan, though. Under the sale agreement, he retained the rights to his chocolate division, but promised to never again re-enter the caramel business against his old company. Initially, he intended to take a break, boarding a boat headed for Europe on what was intended to be a long cruise. But it didn’t take too long before he turned back.

Hershey, it seemed, wanted to build a utopia of his own. His plan was two-fold: he intended to build a new town, somewhere in the East Coast, designed to be the headquarters for his new chocolate company and a utopia for all its employees. He ended up purchasing 1200 acres of underdeveloped land in Dauphin County, the heart of Pennsylvania dairy country.

This location tied into the second part of his plan: Hershey wanted to develop a milk chocolate of his own. He knew that his dark chocolate — which was all the chocolate division could produce at the time — was too strong and too bitter for widespread appeal, and too expensive to boot. Milk chocolate would be sweeter, have a mellower flavour profile, and be cheaper to produce and sell.

The only problem: Hershey intended to come up with a milk chocolate recipe from scratch, on his own.

This was a much harder problem than you might think.

Joel Glenn Brenner has a wonderful passage in The Emperors of Chocolate that sets the stage for what was about to come:

We savour milk chocolate, but we also take it for granted, knowing little of the centuries-long struggle to combine these two flavours. Few realise that milk and chocolate are natural enemies: Milk is 89 percent water, chocolate 80 percent fat (cocoa butter). And just as oil and water don’t mix, so it is with milk and chocolate. Milk also contains a lot of butter fat, which has a tendency to turn chocolate rancid. And its molecular structure doesn’t match well with chocolate’s, resulting in a product that tends to be lumpy instead of creamy smooth. For these reasons, milk chocolate is a surprisingly recent invention. For centuries, it eluded the efforts of monks, doctors, chemists and chefs. By the time milk chocolate was mastered, inventors had already unlocked the secrets of the submarine (1775), the electric streetcar (1834), the telegraph (1837), the camera (1839) and the machine gun (1861).

In 1875, Daniel Peter of the Swiss General Chocolate Co. joined forces with the chemist Henri Nestle, an expert of milk products, to produce Nestle brand milk chocolate. The secret to Nestle’s success was condensed milk — a drier, more stable form of milk, which Nestle had also invented. It would’ve been nice if condensed milk was the only critical ingredient for milk chocolate, but Nestle’s original process took about a week from start to finish: the company had to add cocoa powder and sugar to the condensed milk to make it drier still, and then the chocolatiers kneaded the resulting dough-like mixture to drive off all the remaining moisture. This mixture was called a ‘milk-chocolate crumb’, and had to be processed with additional cocoa butter, chocolate liquor, vanilla, salt and sugar and ground for days to make it smooth ... before finally being turned into bars of milk chocolate. Nestle’s original process was laborious and expensive, to say the least.

But it was worth it. Overnight, milk chocolate became all the rage in Europe. Manufacturers scrambled to copy Nestle. Since the original formula was carefully guarded, copycats had to come up with their own approach to milk chocolate. Some began experimenting with powdered milk (which solved the milk supply issues Nestle struggled with); others began experimenting with different milk condensing methods. In England, manufacturers began combining partially evaporated milk with sugar and chocolate liquor before drying out the mixture. The resulting crumb lasted even longer than the mixture from Nestle’s condensed milk process.

Unsurprisingly, each method produced a slightly different milk chocolate flavour. Since people tend to prefer the flavour of the chocolate they grew up with, the emergence of different manufacturing techniques resulted in different national preferences over the course of decades. So, for instance, the British prefer the caramelised flavour of Cadbury, the Swiss prefer milky Toblerone and Lindt, and Italians love the dark, creamy flavour of Baci.

Not that any of these methods were of any use to Milton Hershey. In the late 1890s, from when he started meddling with the chocolate division in the Lancaster Caramel Co, to the start of the 1900s, when he began experimenting for his new chocolate company, Milton Hershey was determined to outdo his European counterparts. This in turn meant that he was going to ignore everything they’d discovered about milk chocolate — nearly three decades worth of experience by this point — and simply go his own way. He had no knowledge of chemistry. He had no experience with milk, much less understood how to work his way around a farm (or around a condensing kettle!) He simply intended to do trial and error.

Hershey started out by purchasing the best equipment he could find. He bought the best condensing kettles to evaporate milk, plow machines to knead the milk-chocolate crumb, the best chasers and melangeurs and so on. He undertook what would today be called an extensive R&D program to invent a new type of milk chocolate. Brenner documents this painful process in Emperors:

Hershey began to experiment with various formulations, assuming it would take just a few months to finalise his recipe (emphasis added). He worked sixteen hours a day alongside four of his most trusted workers. At 4:30am, they woke to milk the cows. Milton’s mother served breakfast at 6am, and then it was on to the creamery for work. Cleanup and the evening milking ended each day well after dark.

At first, the trials were simple. Milton knew nothing about running a dairy farm or processing milk, and he spent the early weeks just learning his way around the creamery. When he began experimenting with condensing, however, everything became more complicated — far more complicated than he had imagined. He assumed the richest milk would make the richest chocolate, so he started working with cream. But the cream was almost impossible to condense without burning, and even when the condensing was successful, the fat content of the cream tended to keep the chocolate from hardening. He tried whole milk, which was better for condensing, but found that it made the chocolate spoil within a few weeks. Since he intended to ship his chocolate long distances, he needed a product that would last. Skim milk, it seemed, was the only answer. He installed separators and began churning out butter with the unused cream and condensed milk with the skim milk. Satisfied with the initial results, he replaced his Jersey cows with Holsteins, which tend to produce milk with less fat.

But he was far from inventing a final recipe. There was trouble with the sugar. When should it be added? Hershey supposed that the right time to blend it in was after the milk was condensed. But after months of trying, he discovered he could not get rid of enough moisture in the milk unless he added the sugar before condensing. The natural assumption — that if the sugar worked that way so would the other ingredients — led Hershey off track again. he wasted many more months trying to add the cocoa butter in with the milk, but it always scorched in the condensing kettle. He tried adding dried and pulverised cocoa powder, but to make it mix he found he had to add water and then boil that out again, which added time and expense. He tried putting the warm chocolate liquor, fresh from the milling machine, into the milk, but the mixture curdled too easily.

Hershey spent three years going nowhere. As he spent those years experimenting, the chocolate business in the United States boomed, with new chocolate companies popping up seemingly every day. One company, Walter Baker, was so far ahead of the competition that it was receiving half of the 24 million pounds of cocoa beans imported into America annually. Rumour had it that Baker was beginning his own milk chocolate experiments.

Hershey was also under pressure to move forward with the first part of his plan — his original dream of building an industrial utopia. He had the land, all 1200 acres of it, but he hadn’t yet started building his factory nor his town, so focused was he on his milk chocolate experiments. Finally, he caved. On March 2, 1903, Hershey broke ground on the new factory. The sprawling complex stretched the length of two football fields, and was meant to house 600 workers and produce millions of dollars of chocolate annually. Hershey bought modern chocolate-making equipment from Germany; he installed cocoa bean roasters, grinders, presses, conches, and everything else he would need to make milk chocolate … that is, once he knew how.

By now the pressure was immense. Hershey had been able to make small batches of milk chocolate at his Lancaster facility — the holdover division of his earlier caramel company. But he had no idea if he was anywhere nearer to a recipe that could be scaled up to massive quantities. On some days, the milk would condense by itself; on others, it would burn or turn out lumpy. And the milk chocolate he produced had a short or inconsistent shelf life. Hershey intended his chocolate to be sold all over America. This required a bar that would keep for weeks. He wasn’t getting anything close to that shelf time.

Brenner has a funny anecdote from that fallow period, in Emperors:

Hershey called in men from his caramel plant to help with his experiments at the Homestead. He had hired a professional chemist initially, but when the chemist burned a batch of milk and sugar that Milton was trying to test, it only confirmed his disdain for “experts”. Hershey then brought in John Schmalback, a worker from Lancaster, who successfully condensed a kettle full of the same mixture in a matter of hours.

“Look at that beautiful batch of milk,” Hershey said when the experiment was over. “How come you didn’t burnt it? You didn’t go to college.” Hershey was so pleased, he handed Schmalback a $100 bill.

Eventually Hershey hit on a workable recipe. Using a heavy concentration of sugar, Hershey boiled his milk slowly, at low heat, in a vacuum. The resulting condensed milk was smooth as silk, and blended easily with other ingredients. It produced a mild tasting chocolate with a light brown colour — a colour and flavour that persists till today. Relieved, Hershey and his team began replicating the recipe in his newly-built factory, and started producing milk chocolate at scale.

But Hershey’s recipe had an unintended side effect, one that nobody understood until chemists studied the recipe decades later: while making the milk solution, Hershey’s method caused the lipase enzymes in the milk to break down the remaining milk fat and produce flavourful free fatty acids. In simpler terms: Hershey’s milk chocolate was slightly soured.

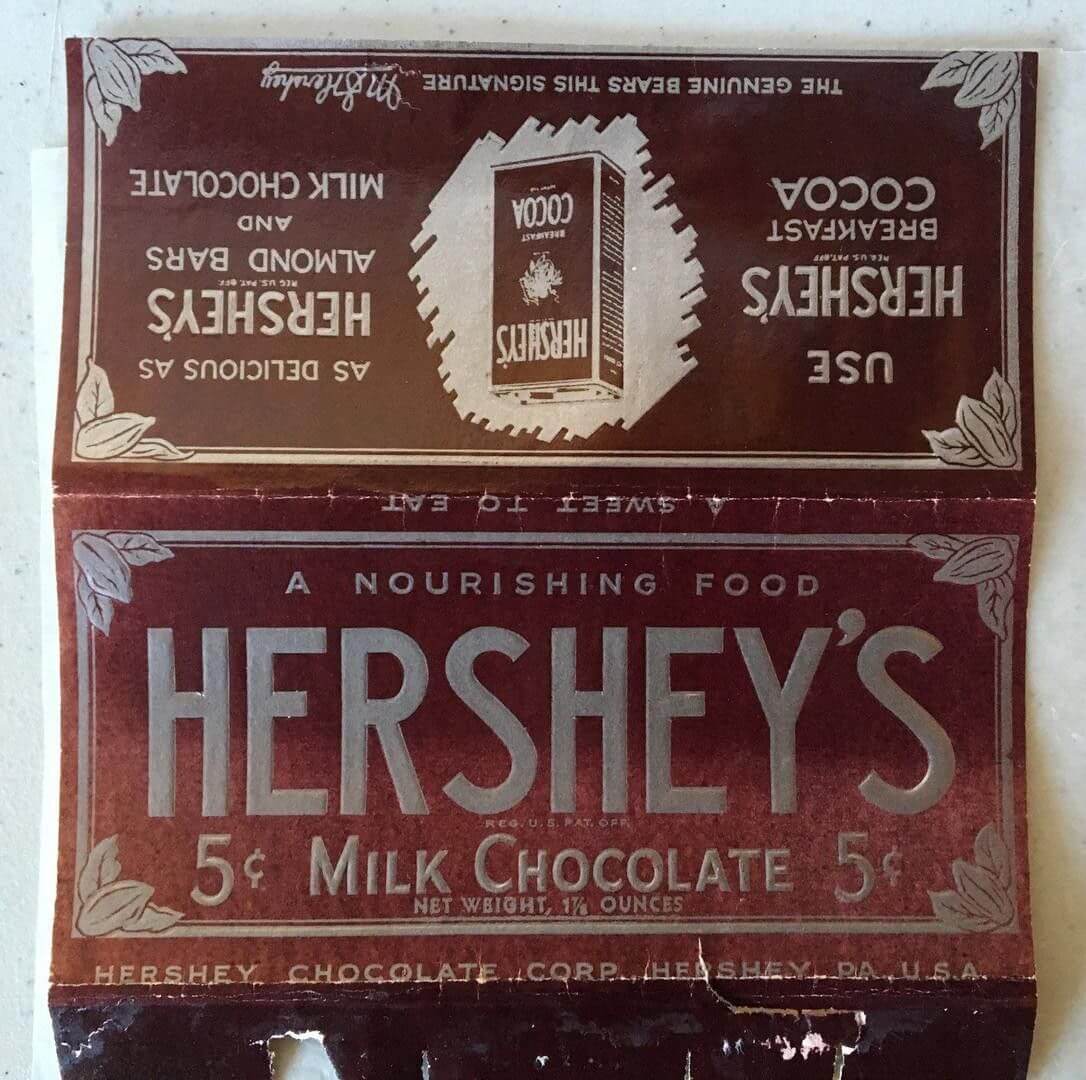

This sour milk chocolate took the American public by storm. They had never tasted anything like it. Initially Hershey launched with a large selection of chocolate products. But after a while, he began to pare down the number of products on offer, focusing only on a handful of items that could be mass-produced and sold nationwide. Hershey made one other decision that sealed his dominance for the next couple of decades: he priced all of his mass-produced milk chocolate products at a nickel.

The strategy was remarkably different from the rest of the industry’s. Walter Baker’s chocolate, for instance, while mass-produced, only sold as far as the Mississippi River. And it was not as cheap. Hershey wanted his chocolate sold throughout the whole of America. This was, admittedly, not a new idea: in Europe chocolate manufacturers had been selling their wares across the whole continent for years. But it was a new approach in America, milk chocolate a new product to most Americans, and the nickel bar a new price point for what was once considered a luxury food.

The company also began to experiment with distribution strategy. At the time, chocolates had only been sold in candy stores and druggists. Hershey wanted a world in which his product were easily available over the counters in grocers, bus stops, newsstands and luncheonettes. He began cultivating a network of brokers — who were emerging at the time to serve retailers across the country — to distribute Hershey products onto such counters in every state, town and city in the United States.

It’s difficult to say whether this was business genius in action. In her initial profile of Milton Hershey in Emperors, Joël Glenn Brenner describes Milton as totally uninterested in the mechanisms of business. The only two things he really cared about was the running of his new town and the intricacies of product. But Glenn Brenner also writes: “These strategies emerged from Hershey’s conviction that chocolate — so rich in nutrients and energy-giving properties — should be consumed by all. So he priced it cheap, forever altering the worldwide market. Henceforth, solid chocolate would be the province of the common man, available in every five-and-dime from Pennsylvania to Oregon. The Hershey name quickly became synonymous with the product, and today, nearly one hundred years after it was first introduced, ‘Hershey’ means a chocolate bar to almost every American.”

Hershey may have charged a nickel for his chocolate and designed his business to distribute nationally out of egalitarian reasons, but the net result of these decisions was that of a winning business strategy: he could grow the company at a good clip, with no external capital, whilst enjoying increasing scale economies. By 1907, the same year Hershey’s Kisses were introduced, annual revenue had reached nearly $2 million — far surpassing whatever business success he’d experience before.

The oddest thing about this story was that the sour flavour of Hershey’s milk chocolate worked in his favour. We’ve already covered the basics: consumers prefer the candy of their youth, and Hershey’s egalitarian distribution strategy guaranteed that most Americans grew up with his unique milk chocolate. As a result, the American market was Hershey’s for the next couple of decades; Europeans were consistently baffled by America’s love for Hershey’s. (Glenn Brenner documents some of European reactions: “Milton Hershey completely ruined the American palate with his sour, gritty chocolate.” sniffs Han Scheu, a Swiss who headed the Cocoa Merchants’ Association. “He had no idea what he was doing.”) Conversely, Hershey’s chocolate never took off in Europe, despite repeated attempts to expand to the continent.

But Hershey’s American empire was good for the next hundred years. Before his death, Hershey bestowed the majority of the company’s equity into an orphanage — his orphanage, for he had no kids of his own — and dictated that most of its dividends go to the foundation’s upkeep. In the process of making his own milk chocolate, he had accidentally built consumer affinity, created a lasting brand, hit scale, and therefore had found a moat, one that ensured the company’s survival for the long term.

Sources

The primary source for this piece was Joël Glenn Brenner's The Emperors of Chocolate.