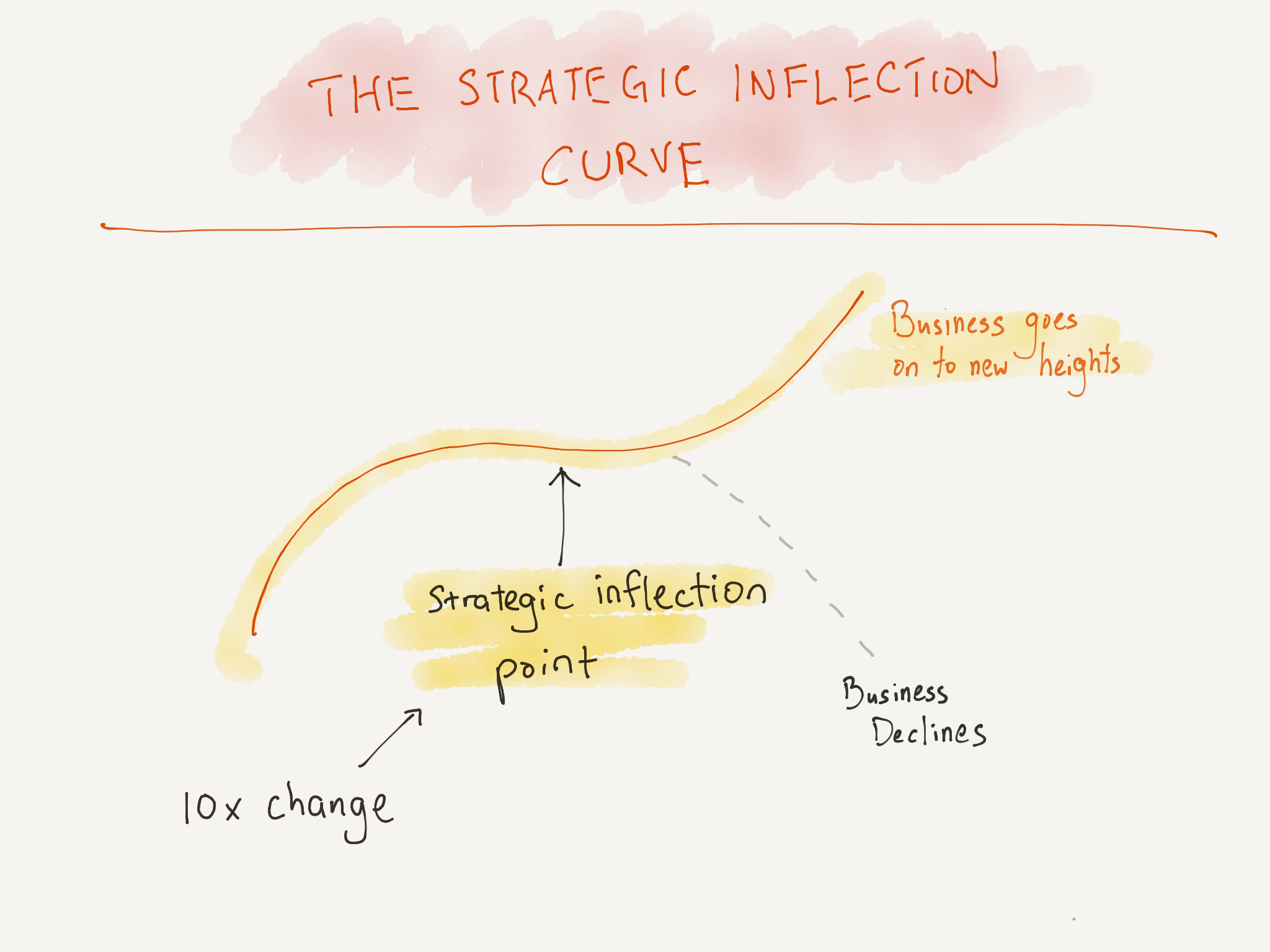

A few days ago I summarised Andy Grove’s Only the Paranoid Survive, a book about navigating “strategic inflection points.”

These “strategic inflection points” are 10x changes that put businesses and careers alike in jeopardy. These changes may be caused by a variety of things: emerging competitors; changing consumer preferences; scientific advancements; government regulation. Intel itself had a near death experience navigating one such strategic inflection point — the emergence of Japanese memory chip manufacturers.

While the causes of strategic inflection points are many, Grove gives us a detailed framework for analysing the threat posed by such changes. He also provides pointers to analyse an emerging technology — a scenario that should be familiar to those of us who work in the tech industry.

It is this framework that I spent the most time on in my summary. What I didn’t summarise, however, was Grove’s application of the framework to the emerging technology of the Internet, which he did near the end of the book to serve as an example to readers. Only the Paranoid Survive was published in 1996, three years before the 1999 peak dot-com boom and bust. This means that Grove applied his framework to the developing technology of the internet and worked out its implications before the hype cycle got real.

I was struck by the fact that many of his conclusions turned out to be correct. This got me thinking: what happens if we applied Grove’s framework to a new technology today? For kicks, let’s pick something new, potentially revolutionary, with a ridiculous hype cycle. Let’s apply Andy Grove’s framework to cryptocurrency.

Cryptocurrency: a primer

(In which I explain cryptocurrency and smart contracts. Feel free to skip ahead if you know all this.)

Cryptocurrency is a digital currency not issued by any central monetary authority. These currencies are often (though not always) backed by a distributed system known as a blockchain. The blockchain serves as a ledger, which is the log of all transactions made over the course of the currency’s history. I won’t explain how a blockchain works in this post; I assume you either understand it, or you have the time to go watch the gajillion Youtube videos that explain it far better than I can.

At some level a cryptocurrency is a currency like any other. But projects like Ethereum introduce another idea on top of this: that of building applications on top of a blockchain. What this looks like is that you may deploy wallets that execute code to the Ethereum blockchain. Unlike normal wallets, these wallets aren't owned by a specific person. They live as independent agents that own money in the Ethereum network, and their actions are defined by the code that was written at the point of deployment. These special wallets are called ‘smart contracts’, and are used for a variety of things.

Smart contracts work by issuing tokens in exchange for money, and performing actions for users who own their tokens. (The act of initially offering a token to the public is known as an ICO — aka Initial Coin Offering). Think of a smart contract as a ‘program’ where the price of usage is the purchase and ownership of a token.

To pick a trivial example, CryptoKitties (a cat collecting and breeding game) is a smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain. You send money to the smart contract and get a ‘token’ in return. This token represents your ‘kitty’. You may use your kitty token to interact with the CryptoKitty smart contract: for instance, you may use your token to trigger an action on the contract in order to ‘breed’ your kitty with another kitty.

The point is that smart contracts have potential. Some projects have implemented organisational voting rights via smart contracts, in the same way that certain classes of stock allow shareholders to vote on board resolutions in a corporation. Equally important to know is that there are large problems with the idea of smart contracts — it's not clear, for instance, what the ideal use case is.

Our analysis must begin by picking a company to analyse. Grove intended this framework to be used to evaluate the effects of an emerging change on a particular business (ostensibly Intel, given his history at the company). I shall pick an investment bank to form the basis of my analysis. My justification is that financial houses would be most affected by an emerging ‘security’.

Let's begin with Grove's framework:

Step 1: Avoiding the trap of the first version

It's important when analysing an emerging technology that we avoid thinking about the technology as it is now. Grove started out with a description of the Internet as it was in 1996, but asked readers to imagine that it was 10x faster, 10x easier to use, and 10x more available. He even asked readers to imagine websites not as the horrible single-page monstrosities that existed back then, but as things created by professional designers.

It's important when analysing an emerging technology that we avoid thinking about the technology as it is now. Grove started out with a description of the Internet as it was in 1996, but asked readers to imagine that it was 10x faster, 10x easier to use, and 10x more available. He even asked readers to imagine websites not as the horrible single-page monstrosities that existed back then, but as things created by professional designers.

Cryptocurrencies are similarly horrible as a version one. They are:

- Difficult to use. (How do you set up a wallet from scratch?)

- Difficult to understand. (Imagine explaining to your parents what a cryptocurrency is.)

- Incredibly slow. (It takes a few hours before your transaction is considered ‘complete’. Under load, transaction speed slows to a tortoise sprint.)

- Very inefficient. (‘Mining’, which is necessary for the operation of a blockchain, consumes a large amount of electricity and computing resources).

- Has a number of technically challenging problems. (Security is one; recovery in the face of a network partition is another.)

It's easy to reject cryptocurrencies based on what they are today. But that would simply be falling into the trap of the bad first version! In order to be sufficiently paranoid, we should imagine the technology at its peak potential. Let's assume:

- Cryptocurrency becomes trivially easy to use. Anyone can open a new wallet for a new cryptocurrency — it becomes as easy as installing a new app on your phone.

- Crypto becomes something that is ‘widely understood’. I don't mean to say that the general public grows to understand the technical underpinnings of cryptocurrency; rather, I mean that people would understand crypto like they understand the Internet: i.e. they know what it can do for them, and how to use it. They do not need to understand how mining or smart contracts work, the same way most people today don't bother to understand how TCP/IP works despite being able to use the Internet.

- Cryptocurrency transaction speeds becomes at least as fast as a traditional bank transaction.

- Crypto mining becomes more efficient. Mining becomes a lot cheaper to do; or there is a shift away from proof-of-work.

- And, finally, we assume that crypto solves all its remaining technical challenges.

The important bit here is to not get too bogged down in the technical details. On a long enough timescale, tractable technical challenges get solved, often in ways we can't imagine today.

If we assume crypto is 10x faster, 10x easier to use, 10x more understandable and 10x more socially acceptable, what happens? This is the most interesting formulation of the question we can answer.

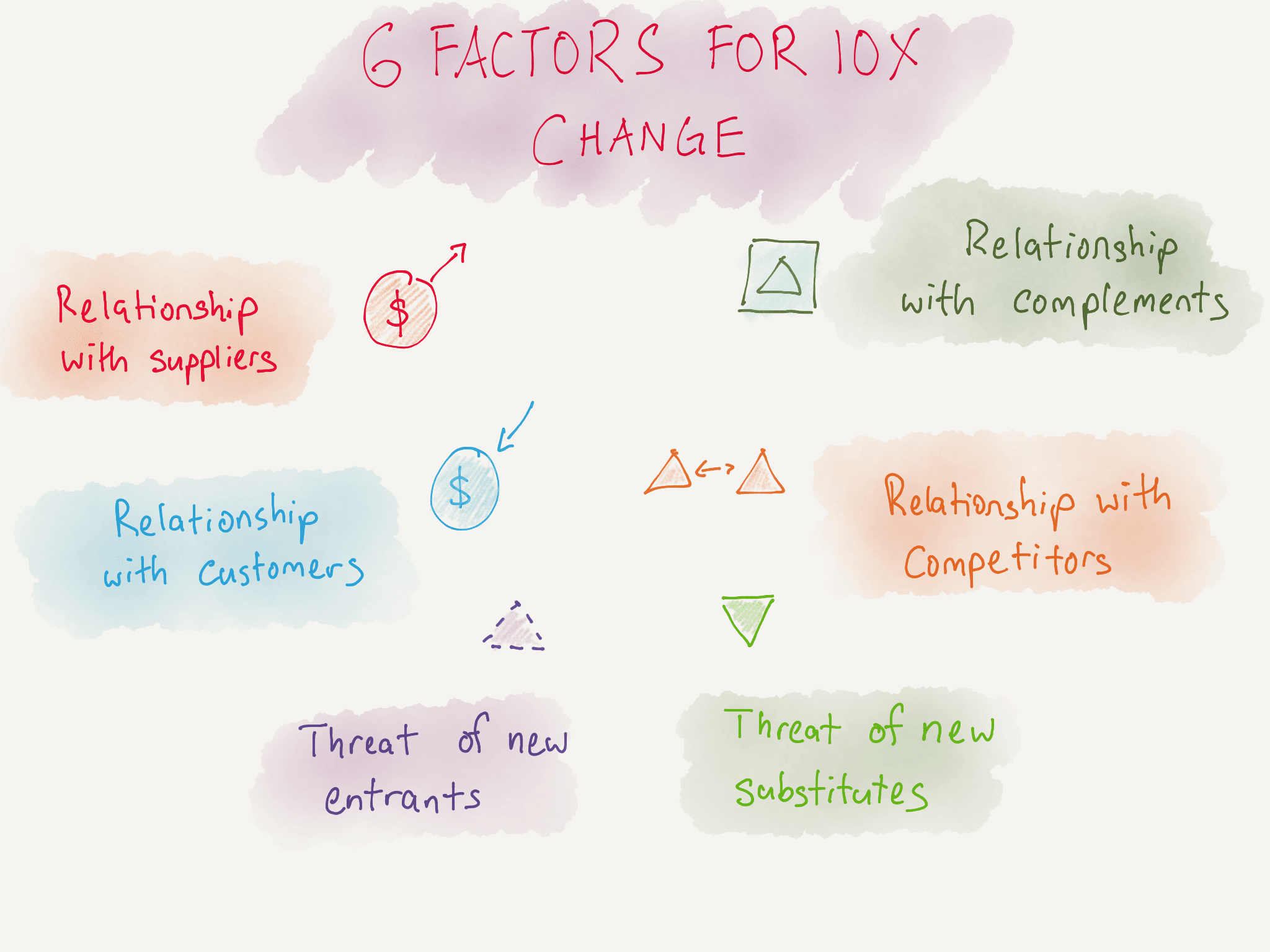

Step 2: Apply 6 Forces Analysis

Grove's next step is to imagine if the emerging technology affects the 6 factors that impact a business, in order to determine if it causes a 10x change in any one of the factors.

Ideally, one should do this on a business that you understand deeply. Since I'm doing this as an intellectual exercise, I'll have to do my best. Do shoot me an email if I'm getting something egregiously wrong.

Let's assume that investment banks have 4 business segments:

- Investment banking — assists corporations to raise capital, go public, restructure, spin off or engage in merger and acquisition activity.

- Institutional client services — advises clients on their portfolios; offers mutual funds and private investment funds.

- Investing and lending — clears huge orders of stocks, bonds and commodities for large institutional investors.

- Investment management — manages its own investments.

We shall see if crypto-currencies affect these business segments in our analysis, as follows:

Relationship with suppliers — Investment banks don't have conventional suppliers. In nearly all their business segments, they take reasonably intelligent university graduates and money from clients, and combine them to return bonuses to the graduates and returns to the clients.

I suppose we may consider institutions and high networth individuals to be ‘suppliers’ to the investment bank, in that they provide the money for the banks to manage. But this blurs the line between ‘supplier’ and ‘customer’. Cryptocurrencies aren't likely to affect this relationship.

Relationship with customers — If crypto ever becomes a valid investment asset class, we shouldn't see much of a change with regard to the investing & lending, investment management and institutional client services business segments. But the investment banking segment could plausibly be affected.

An example here is Goldman Sachs helping Apple to offer $17 billion in bonds in 2013. In this scenario, corporations like Apple is considered the customer, and investment banks provide a service to supply these customers with capital.

Cryptocurrencies may affect this relationship. ICOs are increasingly seen as an alternative way for companies to raise money. If doing an ICO is an order magnitude easier to do for the same amount of capital as compared to the bond markets, we may see a decline in the need for bond offerings in the near future. This bodes badly for the investment banking business segment.

There are two possibilities here. The first is that the regulatory environment catches up and regulates token offerings the way they do bond offerings. The second is that they don't, and we get a fantastically easy-to-deploy financial tool for corporations to raise capital.

Threat of new entrants — Our previous discussion of a non-regulated ICO environment leads nicely into this next section. If the ICO is a valid alternative to a bond offering, we should see an explosion of boutique firms offering ICO services to companies looking to do token offerings.

Investment banks are large, heavily regulated organisations. They aren't likely to lead the charge into the ICO fund-raising space. But it is likely that investment banks would be able to acquire such firms in order to offer ICO expertise of their own.

Relationship between business and its competitors — See above. It's difficult to imagine token offerings completely displacing bond offerings. But if token offerings become the instrument of choice for corporations looking to raise additional capital, then we should see a number of strategic investments by investment banks competing with each other, at least over the next couple of years, with a period of consolidation after that.

Threat of substitutes — We've been working on the assumption that an ICO is a substitute for a bond offering. It is probably a good idea for us to pause at this juncture to consider how else an ICO might differ from a bond offering, and what advantages — if any — it might have.

The first and most obvious difference is that an ICO isn't debt. Unlike a bond offering, the corporation isn't on the hook for repayment at a certain interest rate. It could certainly be set up to look like debt, but I'm not sure if many companies would chose to do so.

The other interesting thing to consider here is that companies do bond offerings because bond markets are more forgiving compared to taking on bank loans. Imagine that a token market exists, and that this market is even more forgiving compared to the bond markets (perhaps to the point of idiocy). This makes token offerings a lot more attractive for corporations.

Crypto tokens that are purchased during a token offering are also not shares, in that they don't represent ownership in the corporation. Instead, it's probably best if we think of these tokens as occupying a strange space between a security and a loyalty membership program.

I chose CryptoKitties as an example because it gives us an idea of what a token may be programmed to do. There are companies today that are considering implementing loyalty programs as a crypto token. These loyalty programs are implemented the same way the CryptoKitties project is implemented: via smart contract on a blockchain. Ownership of the token then provides benefits to the owner — be it through loyalty points, or other member-only exclusives.

I think there's something to this idea. Imagine a world where fans of a company buy and trade tokens. You hold Nike tokens for membership-exclusives and promotions; once your passion for Nike fades, you sell your tokens back to the corporation, or sell them to other users, or trade them for Adidas tokens.

In this formulation of the future, ICOs are, in essence, securitising brand loyalty. This isn't that bizarre: see for instance the behaviour of millennials with regard to the Snapchat stock:

For some millennial investors, loyalty to one of their favorite apps matters more than financial details in the case of Snap Inc.

(...) “I bought it even when I was pretty positive I would not make a profit in the short run, but just because I am a fan of the product,” said Chris Roh, a 25-year-old software engineer in San Francisco, who has only been trading stocks for about a month on Robinhood, a mobile trading app popular among millennials.

I believe an ICO might make for a credible substitute to existing means of raising capital. The corporation gains all of the capital benefits of a bond offering; the token captures consumer loyalty, and the companies that offer ICO services take a happy cut.

Relationship with complements — I can't imagine what a complement to an investment bank might possibly be, so I'm going to leave this one blank.

Conclusion

Step 3 of Grove's framework is to rinse and repeat this analysis every time a new development occurs. We should rightly consider my analysis a reflection of our current times, and we should feel free to repudiate it as new events occur.

If we assume the future pans out the way this analysis says it would, then it might be very lucrative indeed to go after the ICO-funding space as an entrepreneur. But as to our original purpose: whether or not crypto-currencies represent a strategic inflection point for investment banks depends wholly on the size of the ICO market at maturity compared to the stock or bond markets. I don't personally believe that this represents a 10x change or a large risk for investment banks; but I may change my opinion in the months to come.

I hope this exercise is useful for you; it certainly was for me.

Read my summary of Grove's Only the Paranoid Survive here.

Originally published , last updated .