This is a summary of an exceptional 🌿 branch book. You may choose to read the original book in addition to this summary — it isn’t very long, and it is very well written. Read more about book classifications here.

Imagine, for a moment, that you are in charge of a publicly-traded company, one that you’ve built up from scratch, 10 years after its moment of founding. Imagine, too, that you realise, over the course of 3 years, that you’re facing an unprecedented level of competition from Japanese companies — companies that didn’t even exist 5 years ago. And now imagine deciding to get out of your old business, shifting your 1000-employee company into a completely new industry, shutting down factories and letting workers go as you do so.

Imagine how painful that would be. Imagine the courage necessary to pull that off. And imagine the confusion for those in the leadership of the company — yourself included — who realise that this shift means the potential loss of their jobs.

Only the Paranoid Survive is about dealing with the kinds of industry changes that put companies out of business. It was written in 1996 by Andy Grove, the former chairman and CEO of Intel, and is built around his experiences pulling Intel out of memory chips and into microprocessors in the face of overwhelming Japanese competition.

That experience is why this book matters. It’s not often you get to see a high-level exec telling you what he’s learnt from one of the most difficult moments of his career, executing one of the most difficult kinds of moves in business.

The bits that concern us here are what Grove says about careers. He posits that a career is simply a business of 1 person, and that everything he says about protecting business interests also apply to protecting career interests:

If you are an employee, sooner or later you will be affected by a strategic inflection point. Who knows what your job will look like after cataclysmic change sweeps through your industry and engulfs the company you work for? Who knows if your job will even exist and, frankly, who will care besides you?

(…) The sad news is, nobody owes you a career. Your career is literally your business. You own it as a sole proprietor. You have one employee: yourself. You are in competition with millions of similar businesses: millions of other employees all over the world. You need to accept ownership of your career, your skills and the timing of your moves. It is your responsibility to protect this personal business of yours from harm and to position it to benefit from the changes in the environment. Nobody else can do that for you.

The book explains how to do this.

Strategic inflection points

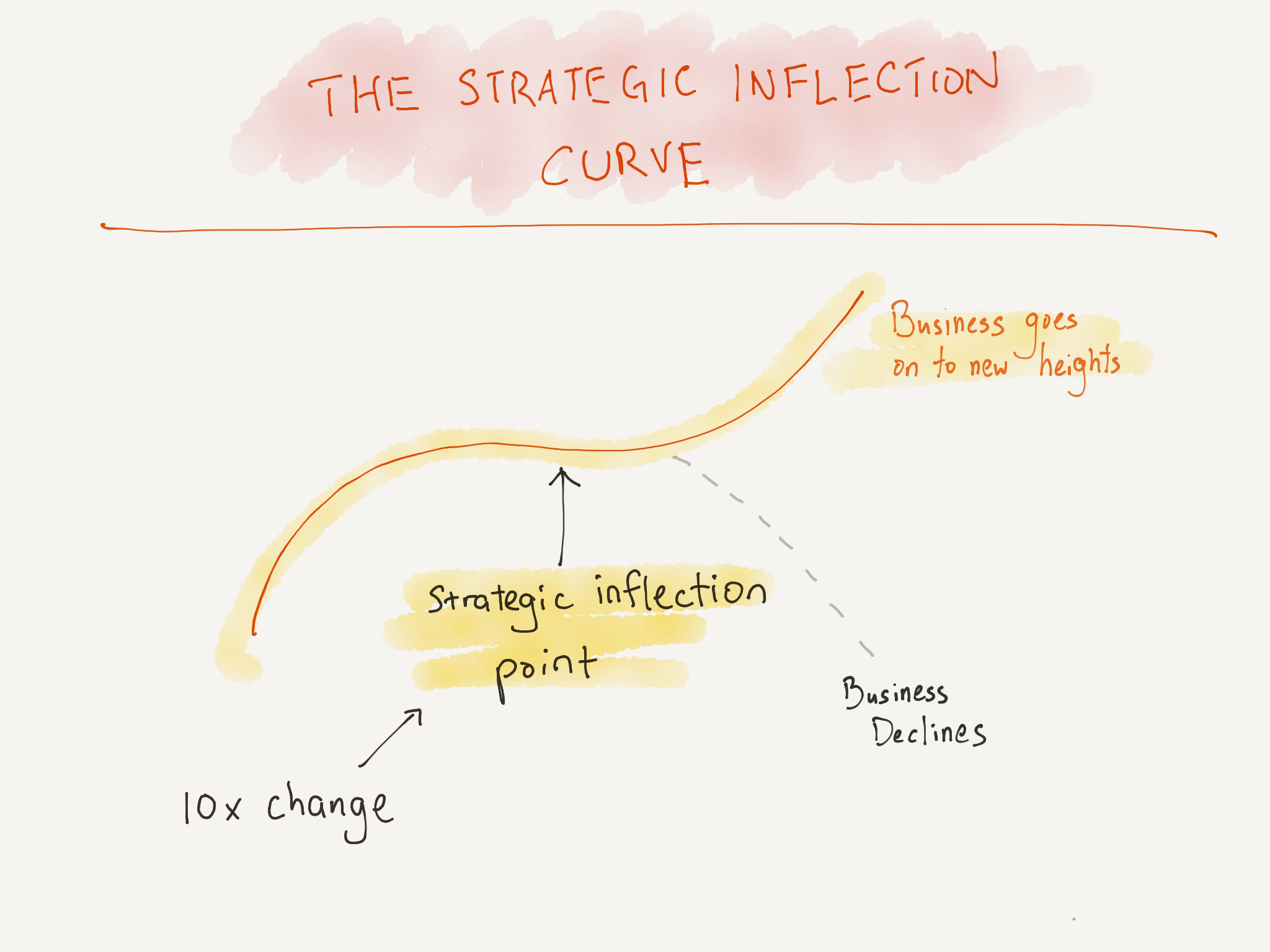

Grove calls the events that can kill businesses and careers alike ‘strategic inflection points’. A good part of the book is spent explaining what a strategic inflection point looks like.

Most businesses have to deal with change: competitors develop new products, business lines incorporate incremental advances in technologies, new regulations shape the external environment. But occasionally, you will find yourself in the midst of a 10x change, one that threatens to transform the very shape of your industry. This 10x change may kill you.

Such a 10x change may come from multiple sources:

- New technology — Grove writes about how ‘talkies’ transformed the movie-making industry, leading to the creation of a new class of movie stars willing to learn to act with sound and voice; other movie stars were left behind.

- Overwhelming competition — A local business faces a 10x change in competition when Walmart moves into the neighbourhood. Intel themselves faced overwhelming competition from the Japanese memory chip manufacturers, causing them to back out from the business.

- A change in supplier power — Travel agents used to make money from airline commissions. When airlines were affected by industry cutbacks in the late 80s, they slashed agent commissions. This changed business fundamentally for the travel agents.

- A change in complementors — The PC industry and Intel have had a mutual dependence on PC software companies. The rise of the Internet could affect that (Grove wrote this in 1996, before the dot com boom and bust, but he got this exactly right).

- A change in regulation — when a patent expires, or the government enacts a new law with material affect on your business, you may face a 10x change that completely redraws the map of your industry.

With this understanding we may now define the strategic inflection point:

A strategic inflection point is the point where a company has to act in response to a 10x change. Grove writes that timing is key: if you time it too early or too late, your business may suffer dearly. But if you time it just right, you would be perfectly positioned to take a lead in the new industry.

A framework for detecting strategic inflection points

The main point of the book is to develop a framework for evaluating strategic inflection points. You can, and should apply this framework to your career.

The framework works like this:

Step 1: don’t fall into the trap of the 1st version — a 10x change may come from many sources, not just technology. But if a new technology emerges, you must be careful to not discount the first version while doing the following analysis. Grove remembers dismissing the Macintosh, as he did the graphical user interface when Microsoft released Windows. Instead, imagine the technology as being 10x better: 10x faster, 10x more professional, 10x better designed. Evaluate against that formulation, not the technology as you see it today.

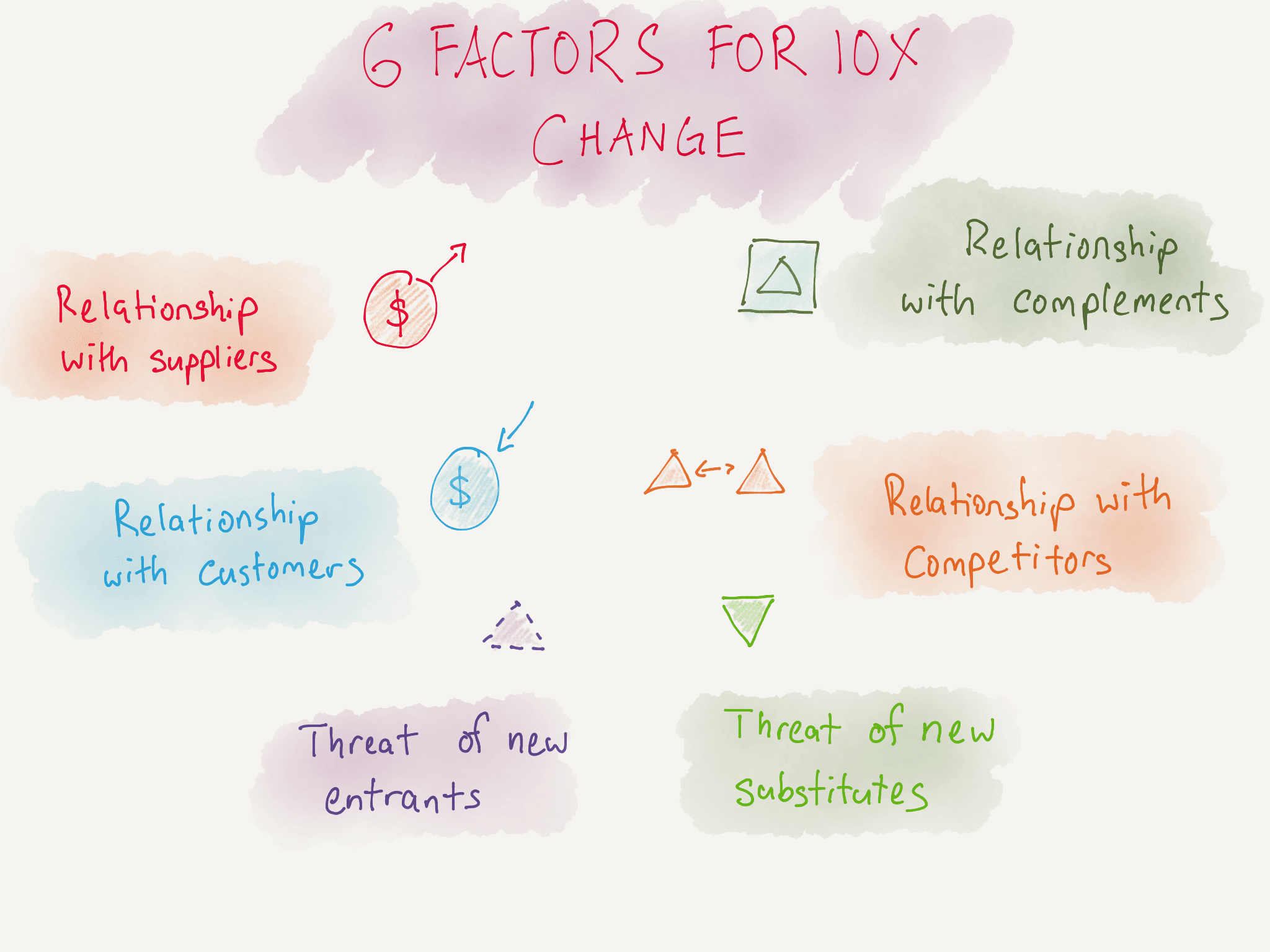

Step 2: apply the technology/change to the following relationships — Grove starts out with Porter’s 5 forces, and adds complementors to that list. You then apply the change to all the forces. In essence, ask yourself: “does this emerging change affect …”

- … the relationship between the business and its suppliers? A change may make your suppliers more powerful, which is bad for you, or weaken them, which you may take advantage of.

- … the relationship between the business and its customers? A change in customer preferences may dearly impact your business, as Henry Ford found out after thousands switched to GM’s line of differentiated cars.

- … the relationship between the business and its competitors? The emergence of an overwhelming competitor (like the Japanese memory manufacturers — who were better and cheaper) may prove impossible to compete against.

- … the emergence of new substitutes to my business? The standardisation of containers fundamentally shifted power to trucking and shipping companies from the railroads. It suddenly became more efficient to use trucks on a wide network of roads, feeding into ports optimised for standardised shipping containers.

- … the threat of new entrants? A patent expiry or a sudden influx of cheaper competitors may fundamentally affect the business. Mainframe computer manufacturers, for instance, could not deal with the new ‘horizontal’ computer industry, where different suppliers at each level of the computer industry allowed buyers to ‘mix-and-match’ components (software, hardware, peripherals) to build or sell computers of their own.

- … the relationship between your complementors? A complement is a business that sells products that are complementary to yours. For instance, computers need software, software needs computers. A change could affect this relationship, like the emergence of the Internet, which reduces the dependence of software companies on software distributors, operating systems, and specialised hardware companies.

Step 3: rinse and repeat — it's unlikely you'll get the full picture the first time you do this. Repeat this evercise every time a new development appears that might change things.

What to do in the face of a strategic inflection point?

First: recognise that the most difficult aspect of this is emotional. Grove, befitting of his background as an engineer, calls this the ‘touchy-feely’ stuff:

“If you are a senior manager, you probably got to where you are because you have devoted a large portion of your life to your trade, to your industry and to your company. In many instances, your personal identity is inseparable from your lifework. So, when your business gets into serious difficulties, in spite of the best attempts of business schools and management training courses to make you a rational analyzer of data, objective analysis will take second seat to personal and emotional reactions almost every time.”

And when applied to careers:

“The stages of dealing with a career inflection point, if anything, are even more emotion-laden than with inflection points affecting a company. Little wonder; after all, you are likely to have invested a lot in getting your career to where it is. More important, you’ve invested your hopes in the further upward trajectory of your career. As signs appear that the curvature is shifting downward, your whole being will work at trying to deny that this is so.”

Coming to terms with your emotions, in order to adapt to a changing reality is hugely important for you to survive. It’s even more important when you consider the nature of timing the strategic inflection point.

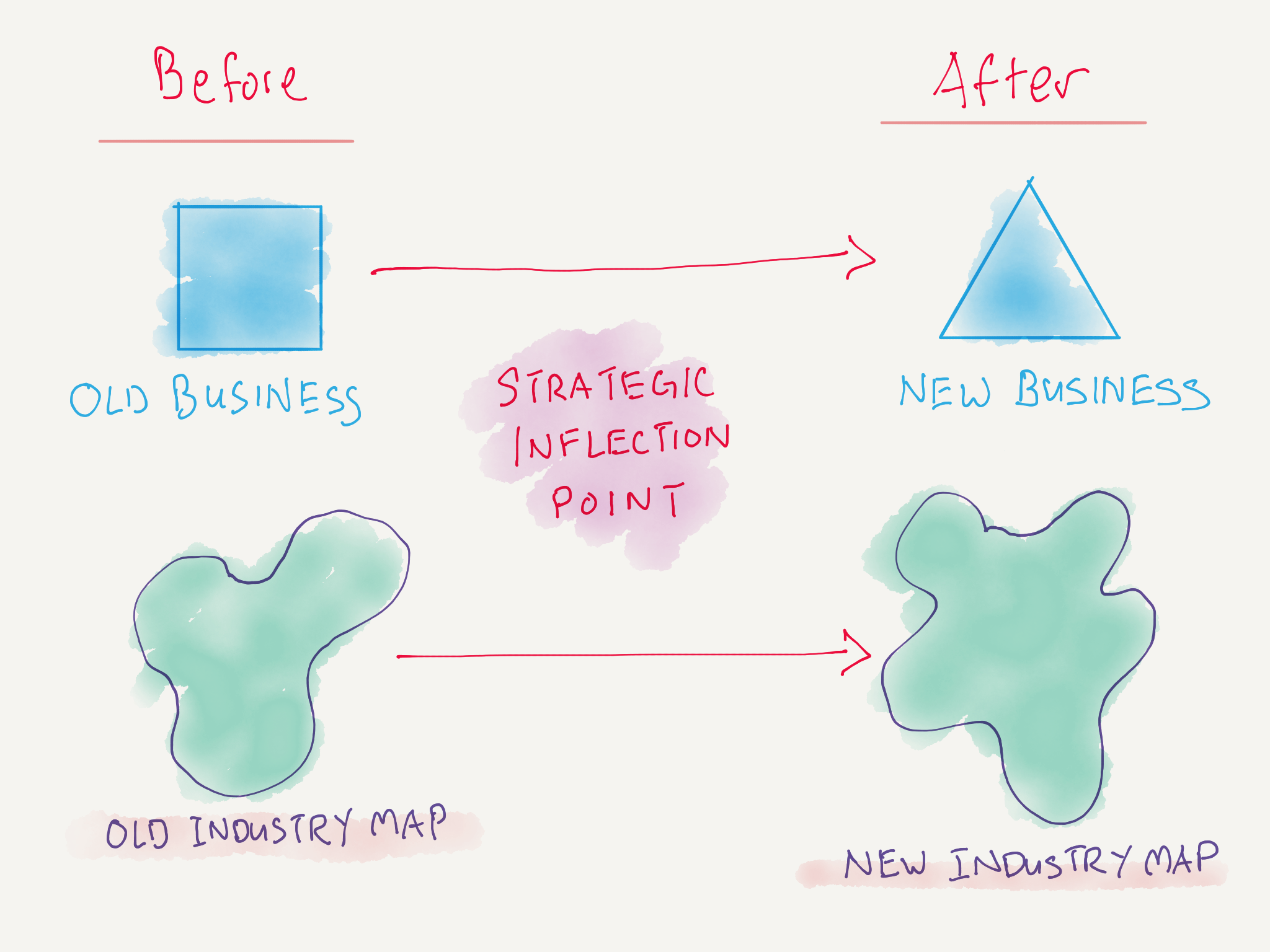

Second: let chaos reign. Grove argues that senior management needs to dial back and listen to the ground for the first half of the response. Especially important is what is known at the ‘periphery’ of the business: the outside-facing functions. Listen to clashing opinions from outsiders, journalists, and critics. Draw a map of the new industry — the industry as it looks after the 10x change has swept through, and constantly update it while debating internally, all throughout the strategic inflection point.

Third: reign chaos in. Once a strategic direction is settled, it becomes imperative that senior managers direct action from the top down, providing context and reasoning to the lower management. This ‘dialectic’ between top-down and bottom-up management is key, as middle management lacks context for the bigger picture.

Grove says the lack of strong top-down management in Intel nearly killed the company, as they had a culture reliant on bottom-up decision-making. Grove also mentions that he responded to every email from every level of Intel during the crucial years of the shift, with the aim of amplifying senior management’s voice and message to all below.

At the end of the strategic inflection point, the shape of the company would have changed, and the map of the industry would also be very different.

Takeaways

All of these techniques can be applied to one’s career. The most important thing to remember, though, is to constantly be on the lookout for 10x changes. Ask yourself if coming changes would affect your employer, the value of your skills, or the external environment for hiring.

Grove warns us that it is too easy to relinquish responsibility for your welfare to your employer, despite knowing that your current job can’t possibly be your last. As you work, keep an ear to the ground.

After all, only the paranoid survive.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Market topic cluster, which belongs to the Business Expertise Triad. Read more from this topic here→