I've made it a goal to read 48 books this year. This works out to be around a book a week, which sounds a little ridiculous. Most people I've told this goal to have told me some variant of “HAHA GOOD LUCK WITH THAT”, presumably because they've tried and failed in the past.

48 books, of course, pales in comparison with the number of books that people like Shane Parrish or Warren Buffet read per year. But then again they're in jobs where they have the flexibility to read during the day. Most of us don't have that luxury; I know that I'm often braindead by the time I get home.

I did a cursory roundup of advice on the web before attempting to start on this goal. Not everything works, because not everyone's context is the same. I optimised my search to begin with advice from people like GQ's Kevin Nguyen — that is, people who held day jobs. I then tested each technique in my life.

Now that I'm 4 months in (and 14 for 48 books, as of this writing), I've decided to summarise the subset of tips I've found to have worked for me. This guide will contain everything I've learnt so far about reading a large amount of books while maintaining a busy, full-time, non-reading job.

Update: It's 30th December now and I've read 50 books this year, two more than my target. Read my reflections here.

Context

Some context before I begin: I read relatively quickly, compared to the majority of my friends. For fiction, I average 100 pages an hour. This shouldn't matter, and it doesn't: as you'll see, reading for your career means optimising for retention.

My goal for reading this many books in a year is simple: I want to rebuild my ability to read books again. I used to read widely in high school. This habit slowed a bit in university; I was too busy with courses and could only read over the summer breaks. When I graduated, I moved to Ho Chi Minh City to run the Vietnam office for a Singapore consulting company for a year, eventually switching to product and building it up to 4.5 million annual revenue over the course of the next 2 years.

Ironically, as I moved deeper into my software career, I began to read less. I still consumed a steady stream of articles, but the number of books I read declined to around 3-4 a year. This isn't good if, like me, you are a knowledge worker, and it doesn’t help if you work in an age of rapid change.

Why read books?

I've argued before that reading books gives you an edge in your career. Reading is the best way to expand the mental models you have for evaluating the world. They provide colour and context in a way that no podcast or Facebook post can. Your career decisions — Jump to another job? Learn that new skill? Go for that promotion? — depend on how well you see the world. Reading matters.

In this, at least, I'm not alone. History is littered with great minds who point to their heavy reading as a reason for their success. There's an argument to be made here about developing better mental models as a result of reading that makes one more effective at life, compared to the person who doesn't.

But there are many other good reasons to read. See, for instance, these arguments:

- Reading More by Paul Stamatiou, where Stamatiou argues for reading for relaxation.

- Read to Lead by Ryan Holiday, where Holiday argues for reading for career growth, though from a different direction.

Whatever reasons you may have, increasing the amount of books you read seems like a worthwhile thing to do.

Stop being precious about reading

How do you read a large number of books? The best place to start, I think is this piece of advice by Kevin Nguyen of GQ: stop being so precious about it.

Reading shouldn't be something that you only do at night, after work, with a glass of wine before bed. If you do this, all the reading you'll do would be when you actually can relax at night, after work, with a glass of wine. If you're like most of us, this is exceedingly rare.

Instead, Nguyen argues that one should just read wherever and whenever you have time. Don't be so precious about it! Read for a couple of minutes while making breakfast, read during your commute, and read while queuing for food. The pages add up.

A half-hour commute can easily turn into five hours of dedicated reading time every week—enough for most people to read an entire book.

Nguyen does a few other things to help him read an enormous amount of books a year. I'll get to those in a bit, but I want to segue to his other big idea, one that's made the biggest difference for me:

Read three books at a time

Specifically, Nguyen works through one non-fiction book, one fiction book, and one comic at any given time. This idea has been a game changer for me. It works because you now have a book that will always fit your mood. Tired and ready to wind down? Have a Dan Brown at hand. Alert and ready to tackle big ideas? Read How Nations Fail.

Later, a friend pointed out that a more effective interpretation is to read one heavy book, one light book, and one very light book, as non-fiction/fiction might not map to difficulty. This is very true — War and Peace is incredibly heavy despite being fiction, while Malcolm Gladwell is so lightweight reading his books are somewhat like consuming empty calories.

Nguyen goes one step further: he reads comics for his 'super light’ category, and reads them during Super Bowl ads.

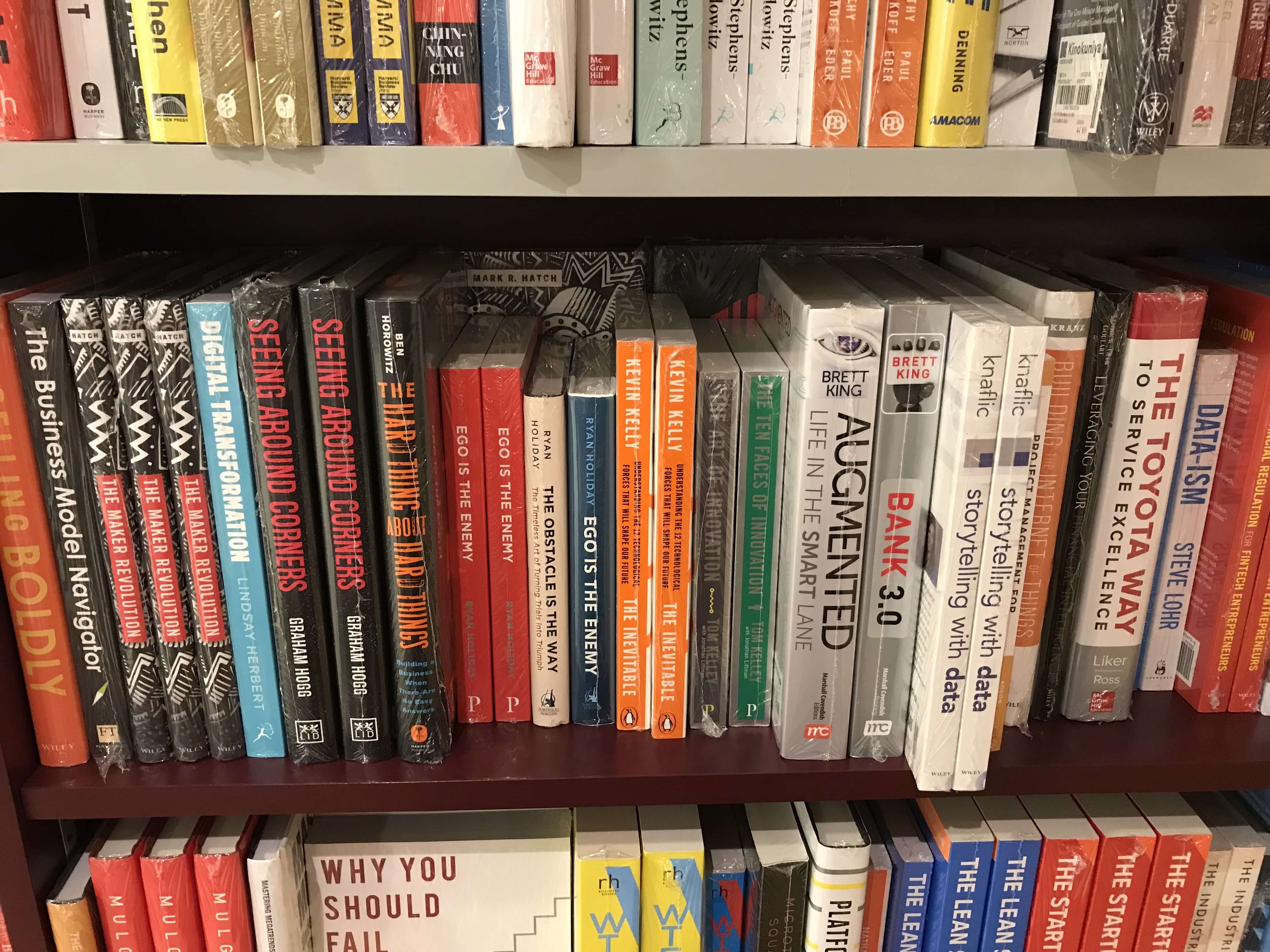

Nonfiction: tree vs branch books

There are, broadly speaking, 2 kinds of “non-fiction idea” book. I've covered this in a separate article, where I talk about the 3 kinds of non-fiction book. We're going to focus on ‘idea books’ for this article; if you want to read about the nuances of all three types, refer to the article linked above.

A quick summary: ‘🌳 tree’ books are books that lay out a framework. After reading this book, you can hang the ideas introduced by other books onto this tree of knowledge, which serves as a map for the ideas that make up the field. A good example of this book is Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow, which lays out all of behavioural psychology (a life's work) in a single tome. Another example is High Output Management by Andy Grove: nearly every other management book can be hung onto the tree of ideas outlined by Grove in HOM.

A ‘🌿 branch’ book is a book that contains one big idea, and then spends the rest of the book working out the implications of this idea in various situations. The vast majority of business books fall into this category. Examples abound: Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Long Tail by Chris Anderson, Radical Candor by Kim Scott.

I've named these two books ‘tree’ and ‘branch’ because branches are a subset of a tree. To generalise a bit, tree books are books about first principles, while branch books are about a single, higher-order idea. Branch books tend to be easier to summarise, as they argue only one point. Tree books, on the other hand, are really, really difficult to summarise.

I hesitate to say that ‘branch’ books are less valuable than ‘tree’ books, as both can be useful. But branch books are a lot easier to read. This brings us to:

Speed reading?

Don’t do it. Empirically speaking, speed reading decreases reading comprehension and lowers retention. You can skim but you shouldn't speed read.

There is an effective way to read quickly, without sacrificing comprehension or retention. However, this technique only works on branch books. The technique, which I lifted from this Harvard Business Review post, goes as follows:

- Check out the author’s bio online to get a sense of the person’s bias and perspective.

- Read the title, subtitle, front flap, table of contents. Figure out the big-picture argument of the book, and how that argument is laid out.

- Read the introduction and conclusion word for word to figure out where the author starts from and where he eventually gets to.

- Read/skim each chapter— read the title, and the first few paragraphs or the first few pages of the chapter to figure out how the author is using the chapter and where it fits into the argument of the whole book. Skim through headings and subheadings to get an idea of the flow. Read first sentence of each paragraph and last. Once you get an argument, move on as it may repeat itself.

- End with the table of contents again, summarise each.

The key insight behind this technique is that branch books are about One Big Idea which the author introduces in the beginning of the book. Then, all subsequent chapters merely work out all the implications of that One Idea. These subsequent chapters are usually padded out, or consist of the author desperately repeating themselves to reach the minimum page count for a paper book.

An implication here is that you won't do too badly if you read summaries instead of reading the full book. A friend swears by getAbstract, which his company pays for. But caveat emptor: such summary services only work for branch books! You're not likely to get as much value from reading summaries of tree books.

Ebook or paper?

One of the biggest questions you'll have when reading in today's digital age is the ebook/paper question. My answer: read narrative on the Kindle; read non-fiction on tablet, phone or paper.

I love paper books as much as the next person. I love their heft, their texture, and the smell of a new book, newly unwrapped from a bookstore.

But there are undeniable advantages to reading ebooks. Ebooks are wonderfully mobile, meaning you can carry them on crowded trains and buses, and read in the rush hour armpit forest. There are also no benefits to owning novels in paper form, unless they are books of special value to you: I own paper copies of Lord of the Flies, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter and East of Eden, but regret pretty much everything else.

There are people who believe in buying paper books to the exception of all else. Ryan Holiday, for instance, owns only paper books, and argues you shouldn't treat them as precious objects. But Holiday lives on a farm in the US. I shuttle between Vietnam and Singapore, and am unlikely to live in a place with enough space for a full-fledged library, at least not for a bit. If you are — like me — stuck in an overpopulated city (and the cities in Asia are vastly more crowded than the cities in the West) then you are also unlikely to consider Holiday's advice practicable.

Reading narrative on a Kindle is the optimal way to do this, in my opinion. I get screen fatigue at the end of the day, when all I want to do is to sit down with a book and unwind. Apart from preventing eye strain, all Kindles are small enough and light enough to slip into my pants pocket. This matters if you don't want to be precious with your reading.

Reading non-narrative non-fiction, however, is a different beast. You should aim to read such non-fiction with a goal of gaining and retaining knowledge. Here the realities of ebooks work against you. Numerous studies show that reading comprehension on screens pale in comparison to paper books, even if nobody really knows why.

These studies also show that the only way to equalise the differences between paper and screen is to read actively: which means highlighting, thinking, and scribbling notes as you read. This is why I read nonfiction only on tablets/phones (where I use the highlighting and note taking features liberally), or on paper (where I can do the same with pen, underlining and writing in the margins). The Kindle doesn't lend itself well to active reading, and I discourage you from reading non-narrative books on it.

There are problems with reading actively like this, however: I've had situations where I've felt resistance to reading on my iDevice, due to screen fatigue. And I've also had situations where I've found myself commuting without a pen, making it impossible for me to read actively. But such is the price of gaining knowledge.

Turn reading into a habit

Nguyen’s advice is useful because it turns reading from an intentional activity into a habit. Habits are a lot easier to maintain, as they happen automatically. You don’t want to treat reading like you would a picnic, for instance — the prep alone is worth procrastinating over.

There’s an idea from cognitive psychology that rewarding behaviour is better than rewarding outcomes. The goal may be to read a book a week, but the focus should be on building reading into a habit. You know you’re on your way to winning when you find yourself reaching for a book instead of Facebook or TV.

Stop reading books you don’t like

The vast majority of reading advice out there argues that you should feel no shame dropping a book that you dislike. I think we can make that advice more nuanced: if you’re not getting much out of the book, drop it. Otherwise, if the advice is useful but not pleasant to read (e.g. Principles by Ray Dalio is like this, for me, as is Average Is Over) then keep at it. You’re still going to make progress due to the ‘read 3 books at a time’ rule.

But let’s be realistic: If you really don’t like a book, and if you know that the book is still worth reading for its ideas, it probably pays to switch to the branch-book-reading-algorithm I outlined above. Skim, scribble down the main arguments the author is making, and keep going. Some books are not worth your time. It’s the author’s fault if their ideas are good but their writing is rubbish.

Last, but not least: let’s deal with the unsaid assumption in this section. Writers who recommend you stop reading books you don’t like assume that you’ve got lots of money to spend on books. I am, however, sympathetic to the folks who don’t have that much discretionary income to spend.

As I see it, there are 3 possibilities:

- Get a library membership. This is the obvious one, though it probably hinges on you living in a country with good libraries.

- Find a second hand bookstore, or online-marketplace for 2nd hand books. My friends in Singapore use Carousell to buy and sell used books. I’d argue buying is better than selling for non-fiction idea books — you want to optimise for retention, which means writing in the margins of the book.

- Piracy. Piracy is illegal, and wrong, but free. Unlike most who write such articles, I grew up in a 3rd world country, on the island of Borneo. It wasn’t a place with a lot of great bookstores. I’m familiar with the necessity of piracy. All I’d like to argue is that you should keep a list of books that have made an impact on you, so that if and when you can afford books, you may go to a bookstore and buy a physical copy of the books you’ve learnt to love.

Conclusion

The stuff that helps me actually read more is simple, then:

- Stop being so precious about reading.

- Read 3 books at a time — one hard, one easy, and one very easy.

- Read ‘branch books’ differently from ‘tree books’.

- Read narrative books on Kindle, and non-fiction idea books on phone or paper.

- Turn reading into a habit, and:

- Stop reading books you don’t like.

I hope this helps you as much as it’s helped me.

Originally published , last updated .