This is Part 8 in a series on tacit knowledge. Read Part 7 here.

It’s been some time since we last talked about tacit knowledge. A brief recap:

- Tacit knowledge is knowledge that cannot be captured through words alone.

- Much of human expertise is tacit: if you’ve ever dealt with someone more skilled than you, asking them “how did you do that?” would often result in a “I don’t know, it just felt right!” response — which is particularly frustrating to a novice.

- There is a ~30 year old branch of psychology research that specialises in the study and extraction of tacit knowledge — specifically tacit mental models of expertise in the heads of real world practitioners. This branch of psych is known as Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM). This is, as you might expect, very useful.

- Most of NDM’s methods for extracting tacit knowledge are quite involved; over the course of the Tacit Knowledge Series, we covered Applied Cognitive Task Analysis, which was designed to be used by domain practitioners (as opposed to trained expertise researchers). I even tested it on John Cutler, who has some pretty remarkable product org expertise.

- Finally, the most important idea — or at least, the most relevant to this essay — is that intuition is not a black box. Early in the series I described something called the ‘Recognition Primed Decision Making model’, or RPD, which tells us how expert intuition really works. This is useful, because it lets us unpack what expert intuition is, which means we can work out how to get it for ourselves.

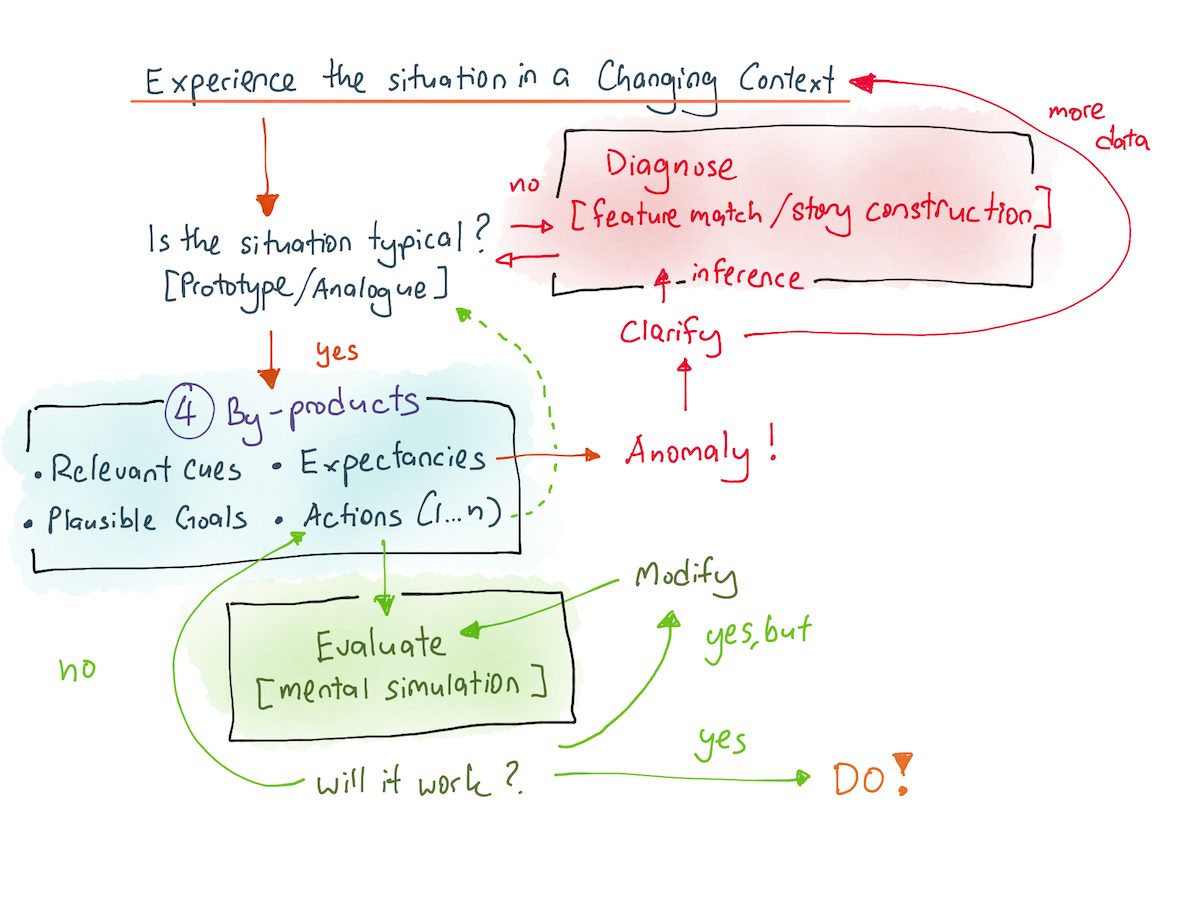

RPD looks like this:

Before you continue further, I highly recommend reading the section on RPD, to get a feel for what it tells us about expert intuition.

I wrote, at the time:

One of the most obvious things that falls out of the RPD model is that we can now use it to carry out cognitive task analysis. In other words, we actually have a shot at understanding what went through my senior programmer’s head.

When interviewing an expert, NDM practitioners will always zero in on ‘tough cases’ that the expert has experienced, in order to examine the recognition-driven process in their heads. Specifically, CTA interviewers will establish a timeline of events of the case, and then ask questions to elicit:

- What cues did they notice first?

- In that particular situation, what did they expect to happen next? (expectancies)

- What priorities (goals) did they have?

- What courses of actions immediately came to mind?

These four by-products is how you get at the tacit knowledge of practitioners.

The problem? I didn’t actually test this in practice — or at least, not rigorously, not over the course of a couple of months, which is really the bare minimum if you want to get decent at something. Which means that I never really understood the method; I was stuck at the lowest level of ‘Put To Practice In Own Life’ on my Hierarchy of Practical Evidence.

It also meant that I couldn’t really tell you how to use the ideas, because I’d not grappled with all the nuances of practice.

Until now.

A few weeks ago, I learnt that Stephen Zerfas had read Commoncog’s tacit knowledge series in 2020, and had used the RPD model to accelerate his own skill when he was put on a ‘tiger team of software engineers, all 10 years senior to me at Lyft.’

I asked him some questions. These are his answers.

Stephen Zerfas’s Experiences Using the Recognition Primed Decision Making Model

All answers by Stephen Zerfas (4 February 2024).

Could you introduce yourself and describe the context you found yourself in when you started using this technique? Feel free to talk about your goals going into this process e.g. were you trying to get better at something specific?

I’m a cofounder of Jhourney, a meditation–BCI startup developing tools to teach life-changing meditation sometimes described as "MDMA without the drug” in record speed. Until recently, these states were believed to require hundreds of hours of practice or more. We believe biofeedback will make them accessible in under 10 hours. During R&D, we began seeing 65-90% of novices entering these states on weeklong retreats without tech. Testimonials are hyperbolic and NPS is 80%. If you’re curious, check out our retreats! We’re scaling these retreats to fund R&D and will layer on tech over time. (RPD was useful to me even in this context, as you’ll soon see).

I was previously a management consultant and then used a coding bootcamp to become a software engineer at Lyft. Both experiences primed me to try CTA. While a consultant, I collected efficiency hacks to cut my hours by 40% and reclaim work-life balance. While teaching myself to code, I collected learning-how-to-learn tactics to try and get a job before money ran out. I wrote about some of these tactics under a pseudonym here.

When I read Cedric’s Tacit Knowledge series in early 2020, I was looking for ways to learn from my software engineering colleagues faster. I had recently been promoted, inherited extra responsibility after layoffs, and started an after-hours computer science program. My colleagues all had over 10 years more experience than me. I couldn’t soak up their expertise fast enough!

The challenge was that they were often helpful in ways that didn’t make sense. I’d ask a question, they’d give an answer without explaining their thought process, and I’d be left with an isolated lesson and limited ability to make myself self-sufficient next time.

The response-primed decision model (RPD) was just what I needed. It helped me to probe my colleagues for their reasoning.

Later on, I used RPD to interview neuroscience experts and tutors while upskilling into an amateur neurotechnologist. RPD helped me code proof-of-concepts for Jhourney, and critically, decide when to bet against experts.

What was your general approach in asking them questions?

Prior to the RPD, I would more or less ask “why” repeatedly. This sometimes worked, but had several failure scenarios:

- My questions were ad hoc. I often thought of more comprehensive and systematic questions later.

- My question quality varied. I would often think of better questions later.

- My questions were re-invented every time. This made it harder to reflect on my ability to learn from colleagues like a virtuoso skill.

- My questions sometimes seemed irrelevant to others. Sometimes my colleagues misunderstood my questions as purely academic rather than serious attempts to upskill myself.

RPD gave me the framework and language to be comprehensive, consistent, and effective by asking about (1) cues, (2) expectations, and (3) alternative actions. (I discovered that in practice I often didn’t need to probe as much on priorities, the fourth part of RPD.)

It also helped me set expectations for the conversation. At one point I even sent a memo to my tech lead summarizing the RPD and linking Cedric’s article so that we’d have shared language for my questions in the future.

Could you tell one story about asking those questions and improving as a result of it?

My memory is dusty, but I recall hitting a stacktrace that looked like complete gibberish while trying to rebuild a Python package on an ARM instead of an AMD processor. Among many other things, it included two characters that seemed unrelated to me: “-v”.

I showed my colleague and asked explicitly about expectations and solutions. He said, “Oh, I bet they forgot to add a ‘-v’ command early in the project’s history and updated it recently, which created an inconsistency in the versions of software you happen to be running. It’s probably a quick one-line change for you. You’ll see where with the changelog.”

I thought that was a pretty magical idea to begin with, but the crazy thing was when I obediently pulled up the changelog and we found nothing. He responded with “That’s a mistake. Sometimes these projects have multiple changelogs and I bet they left it out of this one. See if you can find another.” I had never heard of multiple changelogs but sure enough, he was right, about both the seemingly secret second changelog, the addition of a “-v” command, and a one-line solution.

“How on Earth were you so confident in your interpretation to conclude the project’s changelog was wrong instead of your guess at the problem!?” I asked. (This was a probe on cues and expectations.) He shrugged it off and said “-v” was a universal symbol. I asked, “Did you imagine any alternatives and why did you rule them out?” He said not really in this case — there could’ve been something very idiosyncratic, but we were definitely going to hunt down the changelog first.

To a senior engineer, my struggle and questions might sound naive. But they helped me update that certain naming conventions were likely a lot more ubiquitous than I realized. I noted they could be used to cue and ideate solutions in the future.

What did you find surprising about this process? What was easy? What was hard?

I was surprised by how easy it was! Cedric says RPD can be abstract and difficult to apply, but I found it elegantly simple and concrete.

The hardest part may be that, like any abstract idea, RPD takes practice, reflection, and a little creativity to get good at. For example, I probably asked “What alternatives would you consider?” 50 times before realizing I should usually follow up with a few rounds of “What else?” until they run out of answers. Naval’s got a great podcast episode with Matt Mochary somewhere about how the final answers to “What else?” are often the best.

I wonder if RPD has a reputation for being difficult to apply because it still just takes reps and time. If tacit expertise is just a long list of prior experiences helpful for pattern matching, then the best RPD can do is help you transfer them faster.

There was one thing RPD unexpectedly gave me that I later decided was far more valuable than transferring expertise faster: it gave me permission to disagree.

How? Whether or not it’s wise to disagree with someone is often a function of relative expertise. If you’re a new student learning from a true expert, most of the time the most skilful way to resolve confusion is to assume the expert is right. You ask clarifying questions, think or memorize what they said, etc. But if you’re speaking with a peer, you want to work together to get to the best ideas. Finding the best idea requires disagreement – the scientific method uses falsification, not confirmation. You’re either trying to come up with alternatives or pitting ideas against each other, neither of which make sense if you assume someone is already correct.

Knowing when it was reasonable to disagree was essential when I left my software engineering job to start Jhourney. I was exploring whether or not to invest years of my life and half of my savings in attempting to do something nobody had done before. In order to do something so contrarian, I’d have to disagree with lots of people with more expertise than me. RPD helped me decide when it was wise or foolish to do so.

I spent about a year reading and talking to experts to decide if the company could work. When an expert was obviously pattern matching off all kinds of prior experience, I’d go full student mode. All my probing was motivating by making sure I could replicate their thinking and avoid mistakes. But if it was clear they had fallen back to sensemaking, then I knew my first-principle-reasoning was just as important as theirs in battling ideas. All my probing was to see if any of my favorite mental models or decision-making tools offered a better rationale than theirs, or to see which of my ideas they hadn’t explored before.

If I had simply deferred to others because they were experts, I don’t think Jhourney would’ve gotten off the ground. What a gift! The biggest regrets in life are often from inaction; I’m grateful ‘permission to disagree’ has allowed me to chase my dreams.

If you were to talk to a junior engineer wanting to use your approach, what would you tell them to watch out for?

One, RPD can leave you with a bunch of possibly isolated lessons, without theory or connecting frameworks. I’d suggest supplementing RPD with any tools that make isolated ideas more useful (e.g. structured reflection, spaced repetition, and DIY attempts). Your mileage will vary, but at times I have:

- Kept an end-of-workday reflection doc with 2-3 ideas each for what went well and what didn’t go well. This can be good for process improvements like getting better at RPD.

- Stored favorite technical lessons and motivating ideas into Anki cards (I get dopamine hits from Anki on my phone like I do Twitter). These can double as a searchable case library.

Two, if you want to learn as fast as possible, RPD isn’t as important as a sense of playful curiosity. I think conventional wisdom is to take your own curiosity for granted. But through a combination of meditation, reflection, and deliberate practice, your curiosity – both magnitude and direction – is shockingly malleable. The ultimate learning-how-to-learn hack is to discover how to get yourself as curious as humanly possible about something valuable to others, and then follow that like a dog chasing a ball.

Once you’ve managed your curiosity, Paul Graham suggests habitually and playfully creating things valuable to others, rather than just consuming content, as you learn. I love that point, and have since found creating, rather than consuming, can 10x my motivation, purpose, and feedback while learning.

More about Stephen Zerfas

Stephen Zerfas is the founder of Jhourney, a startup teaching people to meditate into "life-changing" states sometimes described as "MDMA without the drug." Their first product is a modernized, week-long meditation retreat that's converting top tech executives (e.g. OpenAI, DeepMind) into angel investors and repeat attendees. They've also collected the largest biosensor dataset on these states in the world, and have plans to build tools like biofeedback to teach them in under 10 hours. You can see 90 seconds of some dramatic testimonials here. Here are links to Jhourney's website, podcast, Stephen’s Twitter, and upcoming retreats. Code COMMONCOG will get $100 off.

Closing Observations

There are three things that leapt out to me from Stephen’s answers:

- The trick of asking for alternatives until the expert ran out is smart — and also a perfect example for why putting these ideas to practice actually matters. There is no way you can get to observations like these by just reading alone.

- That Stephen didn’t find it that important to ask for a prioritised list of goals! (Perhaps there are other ways at getting at those priorities? But I don’t currently have access to a practice domain here, so I can’t say, and will defer to Stephen).

- And finally, the fact that Stephen feels that as good as RPD is, this crystallised knowledge, plucked from the heads of experts around you, is no replacement for some coherent theory of the domain.

I have more questions, but I am limited by my practice domain right now. I hope Stephen’s answers will give you more ideas for future experimentation — and that you’ll send them to me when you find out! Speaking for myself, I’ve got a couple more ideas to try out now, and I can’t wait to be put into a context where I can use it to see for myself.

Till then. Godspeed.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→