This is the last public post I’ll write for 2020. Commonplace will be on a break from 21st December to 3rd January, though I’ll still remain active in the members forums. See you next year!

Every project that you work on has a clock built into it. That clock is tied to the half-life of your enthusiasm. The tricky thing is that — most of the time — you can’t tell the half-life for a given project before you begin. The only way to figure it out is to start.

Earlier this year, I was working on two projects at the same time: Commoncog, and a content site named Management For Startups. Commoncog gave birth to this blog, so you probably know what it’s about. MFS was about management. I was a pretty good manager at my previous company, and I had trained three people to replace me before I left. MFS was my attempt at turning the training program I had created for them into an online resource. I spent more than a year on it; I also started a podcast and published a book in late 2019, titled Keep Your People.

I killed the project earlier this year. It turned out that my enthusiasm for management writing decayed rather quickly, especially in the context of when I was doing it — I was terribly affected by the lockdown during the worst of the global pandemic.

Shortly afterwards, I doubled down on this blog.

*

I know what you’re thinking: you think that I’m going to wrap this post up with some pithy remark about how you need to test projects in order to figure out what you truly like, and then use that insight to find projects with high enthusiasm half-lives.

Heh, if only things were that simple.

We don't have to look too far for possible counter-examples. Take, for instance, the following two scenarios:

Burnout in Successful Companies

There’s a famous saying in startups circles that “people don’t burn out over successful companies.” This is somewhat true — but only up to a certain point.

At my previous company, my boss was badly burnt out when he first hired me. I took over the consulting piece of the business so that he could take some time off. About a year later, he had recovered enough to return; he pivoted the entire company to selling point of sales systems.

The early months were rough. I remember asking him, in the wake of a botched client deployment, if he was happier executing on this idea.

“Yes,” he said, “It’s harder to burn out when you’re seeing success.”

I couldn’t argue with that: we were making in a month what we used to make in a quarter. It was a relief that the business had legs.

Success ameliorates the pain of low enthusiasm. You can keep going for much longer when you see traction, when your revenue graphs are up and to the right. Though, again, this is only up to a certain point. Most founders wear out after a decade of hard execution.

Burning the Boats

It is surprisingly possible to push through short periods of low motivation — especially when you have your backs up against the wall. In 2005, entrepreneur Rob Walling bought a small app called DotNetInvoice. He spent most of his business capital purchasing the app, and then discovered that he had been duped — the software was terribly written, and the owners had juiced the sales numbers before selling it. He said, of that period:

I kinda look back with terror — because that $11,000 cheque I wrote for this app was pretty much all the money I had in the business bank account. That was all side work that I had been doing. And it was a tremendous investment for me. It was very scary. So when I wrote the cheque and got the code and the customers were all mad … “what had I done?” — was what went through my head. What had I just done? I could’ve bought a car or two — because really most of my life I’ve only driven used cars, and I just dropped all this money and I’m screwed now. And my back was to the wall. And that’s something I’ve talked about in the past — there’s something about — I couldn’t give up, I couldn’t just quit. I couldn’t let myself do that because … my back was to the wall because I’d written that big cheque, and I felt like I was on the hook for that, and I had to bring it to fruition … or else, admit that — I don’t know — admit that this wasn’t possible? Admit that I couldn’t do it or just that it wasn’t a feasible approach? And I couldn’t let that happen. And so I did 60 hour weeks for a couple of months to turn it around.

There’s a reason ‘burning the boats’ (and closely related sayings, e.g. ‘point of safe return’, ‘crossing the Rubicon’, ‘fighting a battle with one’s back against a river (背水一戰)’) exists in our vernacular: throughout history, commanders have known the motivating power of deliberately passing the point of no return.

In theory, enthusiasm half-life is a static value, attached to a project, tied to our interests, abstracted away from the context in which execution occurs. In practice, motivation is a little elastic. Burning your boats — whether symbolically or otherwise — appears to be a rather effective way of extending your half-life … the same way traction appears to be rather good for extending founder motivation.

A Better Model for Motivation

So how to think about enthusiasm?

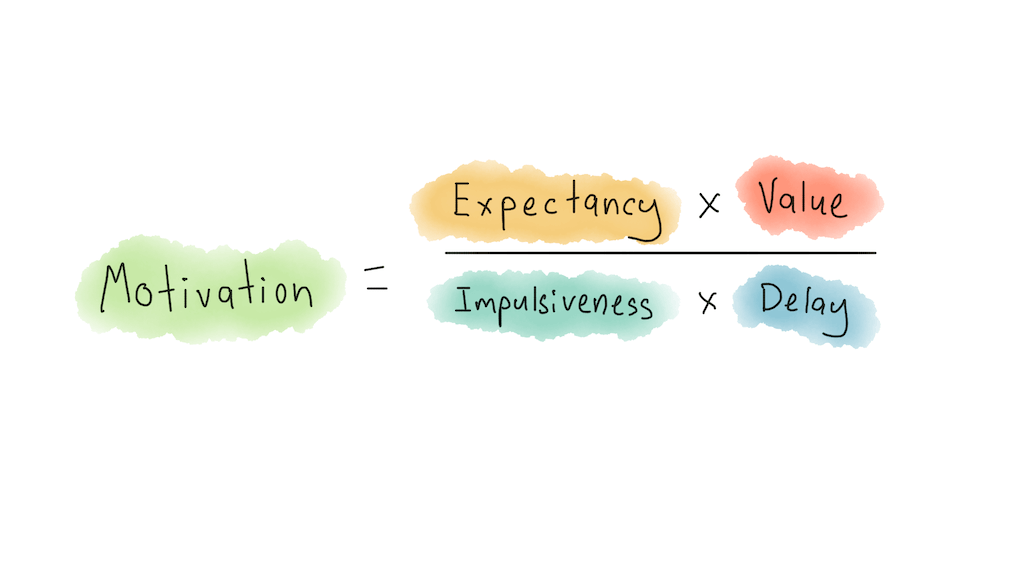

In 2007, Piers Steel published a meta-analysis titled The Nature of Procrastination. In it, he laid out something he called ‘Temporal Motivation Theory’, more popularly known as ‘The Procrastination Equation’ (which I’ve written about elsewhere):

The terms are explained as follows:

- Value — how much you enjoy doing the task, and how much you’ll enjoy the reward from completing the task.

- Expectancy — how much you expect to succeed at doing the task, and how much you expect to acquire the reward.

- Impulsiveness — how likely you are to be distracted given your environment or your history (personality, energy levels, genetics, whatever), and how good you are at staying focused.

- Delay — the further away the task’s reward or completion, the lower the motivation.

In a sentence, the equation says that higher value and higher expectancy increases your motivation; higher impulsiveness or more delay lowers it.

I’ve long used the Procrastination Equation as a method of fighting procrastination. More recently, however, I’ve begun to think about Steel’s work in the context of broader motivation. Steel is an academic. By most measures, he is careful to talk about his theory in terms of procrastination alone. In 2006, however, a year before his meta-analysis, he wrote a paper arguing that Temporal Motivation Theory integrates the ‘most enduring and well accepted basic features’ of prior theories of motivation.

A general theory of motivation is somewhat more ambitious than an explanatory framework for procrastination. But my scepticism aside, I’ve found that the ‘procrastination equation’ is good enough to be useful. It helps explain, for instance:

- Why I dropped MFS: the pandemic was decreasing the perceived value of management writing (at least in my eyes!), along with an increase in impulsiveness (I was compulsively checking COVID-19 stats every few hours).

- My boss was perfectly willing to put up with a shit ton of shlep in the pursuit of a successful, albeit boring, business idea. Why? Because of a) the value he got out of it (the business made lots of money!) and b) the expectancy of success (it was clearly working!)

- Why ‘burning the boats’ works so well — because it increases the value of completion. I should note that it does this in a weird, inverted manner: in Walling’s case, completing the task was valuable because failure was an identity-shattering outcome; for Julius Caesar, ‘crossing the Rubicon’ was hugely motivating, because the alternative was death.

- Finally, the theory suggests that the most enduring form of motivation (high value, high expectancy, and low delay) is a relentless obsession with the subject itself.

I’ve been thinking about Steel’s theory more and more, as the pandemic has progressed and taken its toll on my mental health. I used to think that I had this whole ‘self-motivation’ thing figured out — had I not gone to Vietnam, worked all-nighters, and figured out how to operate in a foreign culture? Did I not do this with little support from others? At the end of my tenure at the company, I figured I could just push through on most low-enthusiasm, high-value projects ... at least for a number of years.

But reality is trickier than that. In theory, I should have been able to execute on whatever project I could contribute unique value to. In practice, the decay of my enthusiasm for certain projects has worked as ballast that dragged the entire effort downwards, regardless of how much grit I had.

I now think that the decay of your enthusiasm can only be manipulated so much. You learn the enthusiasm half-life for your current project as you go along — and later, you ignore it at your own peril.

Originally published , last updated .