The biggest takeaway I currently have from Cal Newport’s So Good They Can’t Ignore You is this idea that building rare & valuable skills is the way you score great jobs.

Those of us who have been working for a bit know this instinctively, of course. But I’ve not seen anyone express it as concisely and as accurately as Newport has.

When I first starting writing Commonplace, I wrote that my goal with this blog was to explore the idea of building ‘career moats’, and I defined career moats as:

A career moat is an individual’s ability to maintain competitive advantages over your competition (say, in the job market) in order to protect your long term prospects, your employability, and your ability to generate sufficient financial returns to support the life you want to live. Just like a medieval castle, the moat serves to protect those inside the fortress and their riches from outsiders.

Newport suggests a simpler way of saying this, which is: just build rare & valuable skills! The rareness × value of your skills is what keeps you employed, after all. It’s what allows you to find new employment when you move, it’s what determines the quality of the roles you apply for, and it’s what gives you security if you're ever at risk of losing your current job.

But Newport leaves the exercise of figuring out what is ‘rare and valuable’ to the alert reader. This is the question I’d like to explore today.

Rare & Valuable Skills in the Pipe Laying Industry

I have a friend — let’s call him John — who works for a multi-national telecommunications company. I don’t know what his job title is, because it’s most likely something generic like ‘senior engineer’ or ‘project manager’ or something equally bland — the point being that his job title doesn’t reflect his true vocation.

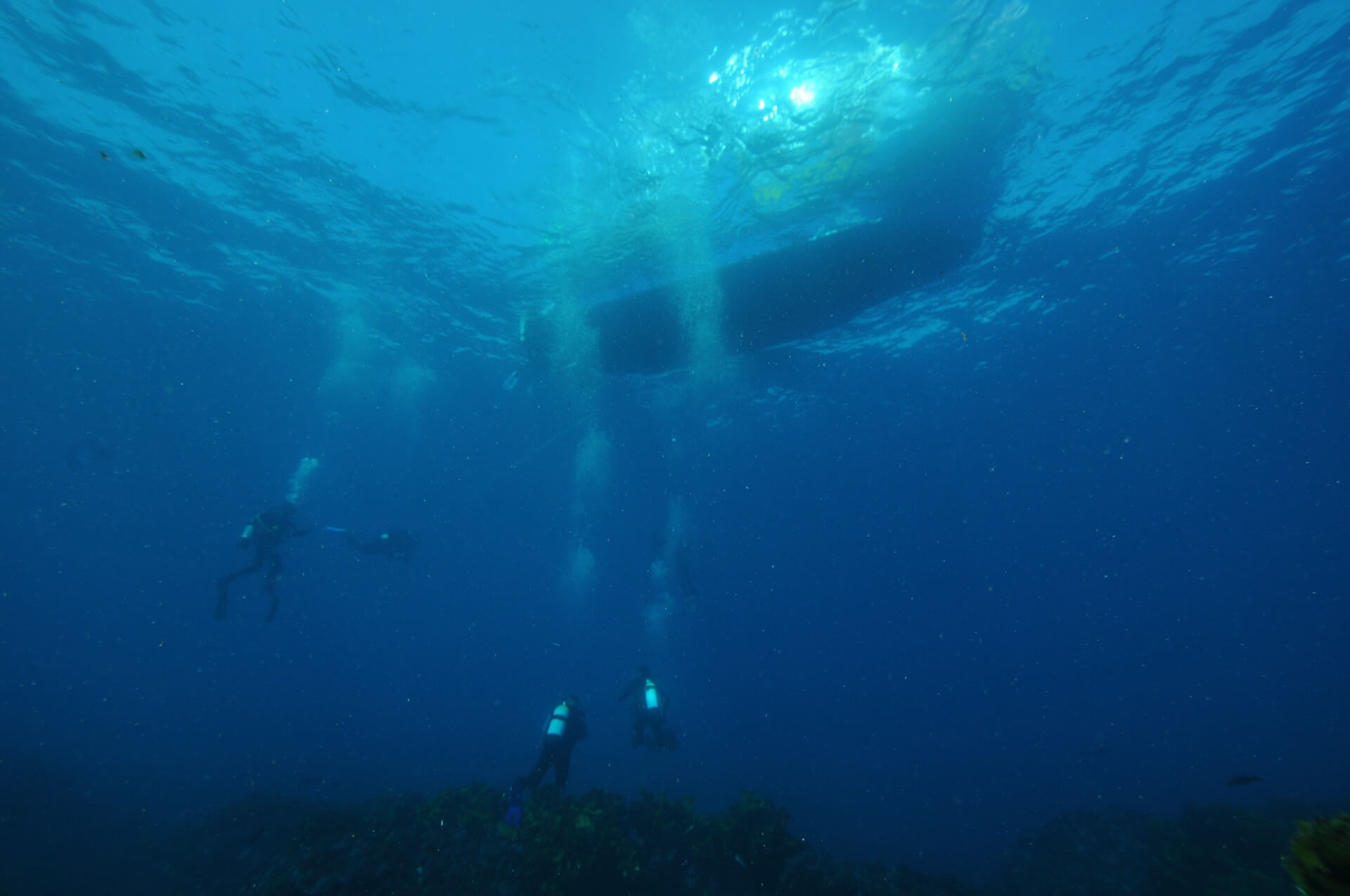

What John’s job really is is that he’s the guy you look for when you need to lay a new submarine communication cable. Submarine communication cables are the things that allows countries to connect to the internet. Let’s say that Vietnam wants to invest in a swanky new fibre-optic internet line, because its current internet pipes get eaten by sharks. John is the person who figures out the exact route — the ‘architect’, if you will, of the internet-pipe-laying industry.

This is not an easy skill. John says that each project is a balancing act: he has to balance budget constraints (everyone needs to make money), physical constraints (ocean beds aren’t nice flat plains), usage growth estimates (this pipe should be good for all the internet traffic today, as well as projected internet usage for the next 10 years!), repeater placement (which boost signal strength but are bloody expensive), shark avoidance (if they’re, you know, a thing) and of course all the logistical concerns such as where the line should connect to the existing grid of submarine communications cables, whether the chosen connection points are good given international maritime law, and whether this new pipe may easily connect to terrestrial receiving stations on our end.

These projects are incredibly complex engineering and legislative messes, and people like John are in such high demand they are engaged in five to six projects at any given time. John no longer does any engineering calculations himself — apparently the industry practice is to assign a group of offshore engineers to each of these ‘architects’; he has a team of engineers in India assigned to him, to whom he outsources the more complicated calculations needed for his projects.

Recently, John was poached by another company in his industry, and was paid a premium for it.

It's clear that John has a career moat: his job requires such a rare and valuable skillset that companies can’t easily replace him with another engineer. He never has to worry about losing his job in the short term, and as long as his skillset is difficult to learn — and so long as governments and companies need internet cables — he can rest secure in his career.

John’s history was as varied and as full of odd stops and starts as many of the other career stories that Newport documents in So Good. But studying John’s story isn’t as useful to us as learning the right lessons from it. We can’t replicate John’s life, after all. But we can draw generalisable lessons, and test them to see if they are applicable to ours.

The Many Variations of Rare and Valuable

The lesson I draw from John is that rare and valuable skills come in many forms, and John's is merely the most developed moat that I know personally; his is one instance of just one type of strategy.

Newport describes only two ways to build rare and valuable skills in So Good They Can’t Ignore You: either use deliberate practice to get good at a single skill (which Newport calls the optimal strategy in a ‘winner-takes-all skill market’), or use deliberate practice to gain career capital in a unique set of skills (what he calls the optimal strategy in an ‘auction skill market’). But it's worth noting that there are many viable strategies when pursuing rare and valuable skills.

I'll describe three.

I have a friend — we'll call her Alex — who is making the bet that augmented and mixed reality interfaces will be an important interaction model of the future. She's going after jobs at the edge of the field — which in this case are jobs that straddle the line between research and product in the big four tech companies in the US.

The ideal outcome for her bet is that AR and VR interfaces take off the way she thinks they will, and she'd have made her name establishing the best practices for UX in the field. This makes her skillset uniquely rare and valuable — she's staked her claim on an area long before it's become clear that it is lucrative or important. But even if this doesn't turn out to be the case, Alex would likely be able to hop to her next opportunity off the basis of her career capital in this field.

Alex's strategy is built around prediction: it’s not yet clear that her field is valuable or lucrative, and she's able to build her skill before it becomes obvious to the masses that it is. There's some foresight needed for this strategy, and some risk, but if it pays off, Alex would be very comfortable indeed.

In contrast, my current career moat was built off the back of a geographical bet: that startups in South East Asia would expand to multiple regional markets in pursuit of growth, and that the ability to run offices in these markets was a rare and valuable skill.

Most people aren't comfortable moving to a foreign country, aren't able to adapt to uncomfortable new cultures, or aren't willing to learn to deal with corrupt, foreign bureaucracies. But I was perfectly willing to do all three things, and I've gotten quite competent at it after three years at my last job. My moat exists for as long as I'm able (or willing!) to move.

(Unfortunately for me this strategy has significant costs: I can't keep my moat if I want to settle down and start a family.)

We could say that my strategy is rare because it's not desirable to work in uncomfortable developing countries. This sort of undesirableness is the same advantage that COBOL programmers have got going for them — banks use large legacy systems written in COBOL, most programmers don't want to code in COBOL, therefore COBOL programmers may command high premiums in exchange for maintaining legacy banking systems. These programmers have a kind of job security that most other programmers don't.

Let's return to John. John's career moat exists because the set of skills required to be competent at his job are varied and rather difficult to learn. A random undergraduate can't graduate from uni and decide to do John's job: for starters, it's not clear that John's job is worth chasing, and it's not clear how to get there.

John himself found his unique complement of skills by hopping from one role to another in his corner of the telecommunications industry — and he did this over the course of a decade, always picking ‘open doors’ that were made possible by the career capital he had earned in the previous step. His path isn’t easily replicable by a fresh graduate, because it isn't linear. It's a far cry from most corporate ladders.

I think John’s moat is built around difficulty, or obscurity. His job isn't obvious; the skills required for it are idiosyncratic and rare, plus there are no obvious promotional paths to get to where he is.

It's important to note that this difficulty is very different from the sort of difficulty that comes from climbing and winning on the corporate ladder. That path is clearer, and the ones who climb to the top do so along relatively straightforward metrics. John's path comes from a random walk towards ever more rare × valuable skills. His path is rare because his walk is hard to replicate.

Using This Idea

I think it’s clear that most of us do not have a career moat as deep and as lucrative as John’s.

Most of my friends are in vanilla software engineering roles, and they're rather undifferentiated — or, worse, they're differentiated on the basis of programming language or tech stack — which is valuable today but not particularly rare, and not very difficult to learn.

Make no mistake: like my peers, as a software person, I, too, am also under threat from fresh computer science grads, who are up-to-date and equally capable in gaining our non-rare software engineering skills. And it probably doesn't help that my industry — the tech industry — has a slight ageism problem.

This might not seem like a problem today — and it probably won't be for awhile. But over the course of decades, my friends and I run the real risk of being left behind by our industry. We risk becoming unhirable.

Which begs the question: how do we use this idea?

The easiest way to use Newport's rule, perhaps, is to ask yourself if you're gaining rare and valuable skills at each stage of your career.

This judgment should occur at the level of potential career moves. Boss wants to shift you to a different team? Thinking of earning an additional degree? Want to move to a different role in a different company? The measure that might matter most is the degree to which the skills that you learn there are rare and valuable.

I think this heuristic is pretty useful. I hope you'll think so too.

Originally published , last updated .