Self help is often said to be full of shit.

People like Tony Robbins exist to sell success as a formula, although his success is in the business of selling success as a formula.

Rhonda Byrne was an executive producer for Australian TV before she wrote The Secret. Byrne’s book — as we now know — is a form of New Thought: a movement that developed in the 19th century, built around the idea that ‘thinking right’ would have a positive effect on your life. In its most extreme form New Thought deemphasises action and promotes only holding the right mindsets. Which — quite predictably — leads to ineffective outcomes.

It is, in fact, really easy to fall into the trap of calling all self help stupid and useless. Luke Muehlhauser wrote an overview piece of ‘scientific self-help’ on lesswrong in 2011, concluding that most self help isn’t scientific. In correspondence with Wayne Weiten, of the department of psychology at University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Muehlhauser reports that Weiten has this to say:

You are looking for substance in what is ultimately a black hole of empirical research ...Basically, almost everything written on the topic emphasizes the complete lack of evidence.

Perhaps I am overly cynical, but I suspect that empirical tests are nonexistent because the authors of self-help and time-management titles are not at all confident that the results would be favorable. Hence, they have no incentive to pursue such research because it is likely to undermine their sales and their ability to write their next book. Another issue is that many of the authors who crank out these titles have little or no background in research. In a less cynical vein, another issue is that this research would come with all the formidable complexities of the research evaluating the effectiveness of different approaches to therapy. Efficacy trials for therapies are extremely difficult to conduct in a clean fashion and because of these complexities require big bucks in the way of grants.

It goes without saying that if scientific consensus exists on a topic, we should defer to it as a source of knowledge. Muehlhauser has a pretty good summary on the state of research on procrastination (with a mandatory how-to article), and I recommend that you read it; procrastination is one of the few areas of self-help where science has useful results and it’s rather silly not to use the research where it’s available.

But what of the rest of self help? How does one derive value from Robbins’s Unlimited Power and Dalio’s Principles and Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People and Munger’s Poor Charlie’s Almanac? Not everything in self help can be scientifically tested. But not everything that can be scientifically tested has value to you.

Think of Self Help as Technê

I’ve found that the best way to read self help is to think of it as ‘technê’ — the old Greek word for ‘craft’, or ‘practice’.

The ancient Greeks had two names for knowledge. Epistêmê was what they used to call ‘knowledge’, and technê was what they used to call ‘practice’. This maps rather loosely to ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ in modern day parlance, but the more precise way of thinking about this is that epistêmê is what we now call ‘explicit knowledge’, and technê is what we call ‘tacit knowledge’.

Explicit knowledge is the sort of knowledge that you can learn from books, or from conversation. I could tell you that Moscow is the capital of Russia, and this knowledge now leaps from my brain to yours, and you gain this explicit knowledge forever. But a musician cannot merely talk about his craft and have his student play as well as he does; this second sort of knowledge, what we call tacit knowledge, is the sort that can be hinted at through words, but which cannot be learnt through talking or reading alone.[1]

I find it most useful to think of self help as this second sort of knowledge.

“But wait!” I hear you cry. “How would you know if the self help you read really works?”

Well. This is easy to answer, isn’t it? If you think of self help as a form of technê, then the implications on your approach becomes obvious.

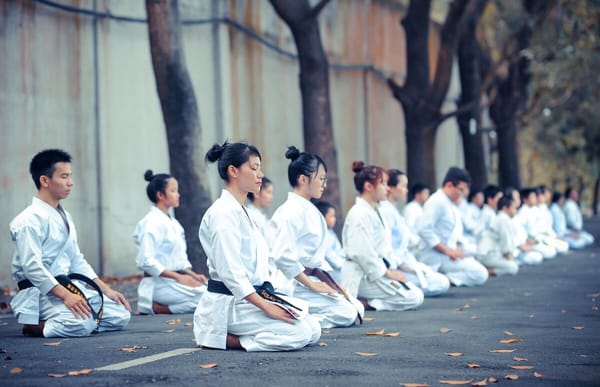

Tell me: how would you know if a martial art works? Or that a recipe to bake a cake bakes it the way it promises?

The answer: by testing it in your life, of course.

Self Help as Martial Art

Treating self help as technê has a number of useful (and obvious!) implications. To make it easier for you, substitute the word ‘technê’ with the word ‘martial art’. Now work out the similarities.

To begin, self help is obviously useless without practice. You don’t learn karate from reading books alone; similarly, you don’t benefit from self help without the crucible of application.

More importantly, not all self help techniques are equally useful, the same way not all fighting techniques are equally usable. Some require too much setup, others only work for a small set of people.[2] The only way to know which it is is to test them: and not just test them in the artificial conditions of a lab or a dojo; but to test them in the real conditions of a fight (or, for self help: in pursuit of a goal).

Obviously, testing here means something quite easy. If you can’t test the self help technique easily, or if the outcomes don’t last: discard the technique like you would any other subpar belief. In other words, optimise for usefulness.

Second, treating self help like you would a martial art means you can apply some common sense smell tests to self help techniques. You may reject the ones that are similar to other techniques you know do not work for you.[3] And you should be immediately suspicious of techniques that don’t past the ‘power test’.

What is the ‘power test’, you ask? Well, difficult problems require powerful techniques to overcome.

I’ve written before that mindset tweaks exist, and that they work when applied to a situation you have control over. But the second part of that sentence is key: you need to have control over that situation in the first place. The power of mindset tweaks is limited; it only makes a difference when used in combination with other things. (It is, in fact, most powerful when you change a negative mindset that holds you back to a mindset that doesn’t. But this is always in the presence of other factors — like actual power to change your situation.) Be suspicious when someone proposes a mindset tweak as a solution for everything.

Third, self help is best learnt from people who know what they’re talking about. You wouldn’t learn Judo from a yellow belter, or even from a blue belter, so why learn business techniques from the likes of Tony Robbins? There are likely better, more accomplished teachers out there, with techniques adapted for your particular industry. I like Ray Dalio’s Principle of Believability here: prioritise testing ideas from more believable people. Spend less time on those who aren’t that believable.

A corollary to this observation is that not all good self help books are ones that are explicitly self-help. If you see self help as merely one instance of technê, then other mediums might be just as useful. Good practitioners sometimes do not write self-help books; they write memoirs. Or they do not write at all: instead, you find descriptions of their ideas in case studies, dressed up as pop science; or from interviews, collected in the ‘just-so-stories’ type of business book.

I find it good to take notice when a testable idea from a believable person jumps out at you. These ideas may come in any form: in pop science books, in interviews, in blog posts. To use a recent example, I read Anne Raimondi’s use of the Trust Equation with some interest, and intend to test its utility the next time I work with someone new. Raimondi passes my believability test.

Fourth, backtesting self help ideas are a thing. The insight here is that you don’t have to test every self help idea that comes your way. If you have enough experiences, you may backtest new ideas on your old experiences, accepting them if you think they would have made a significant difference to your practice.

As a simple example, I read David Hough’s Proficient Motorcycling earlier this year. I’d lived and motorbiked in Vietnam for two years at this point; in the first chapter, Hough writes:

I happened to be along one day when the MCN editors were picking up a test motorcycle for a photo shoot. Mostly, they were engrossed in details of the new machine, the fleeting time, the need to find a photogenic location, and the urgency of beating the evening rush hour. The dealer, obviously a veteran rider, was on a different mental plane. He knew I wrote skill articles, and he offered some advice about one small but important detail: adjusting mirrors. “Most people adjust their mirrors so that the view converges behind the motorcycle. I figured out that it is more important to see more of what's coming up in adjacent lanes. So I adjust my mirrors more toward the sides.” As we rode away with the test machine, I observed that I also adjusted my mirrors far enough outward that I could pick up only a corner of the saddlebags at the inside edges. Big deal! you may be thinking. Who cares how the mirrors are adjusted? Let's get to the really important stuff!

Well, maybe a helmet full of such small details adds up to the important stuff.

I read this paragraph with a jolt of recognition. Twice, I had nearly come to an accident while riding along a straight road; both times, a motorcyclist had come close — a hair’s-width — to hitting me as I swerved to avoid a manhole cover. My mirrors converged to the back of my motorbike, and I couldn’t see far enough on the adjacent lanes. If I had read and applied this piece of advice earlier, my near-accidents wouldn’t have ever happened, as I would have seen farther out. I adopted this piece of advice immediately.

A more sophisticated example suffices: I remember reading Kim Scott’s Radical Candor with something approaching wonder — it explained many of the intuitions I developed while learning to manage people. I noticed that personally caring — despite warnings from my boss that this was ‘unprofessional’ — helped me when it came to handling difficult people problems.

Giving a shit made my people problems tractable, or so I liked to say. And Scott’s book outlined the contours of this particular technique; it gave me new ideas for pushing my practice forward.

The flip side of backtesting also holds true: if you can think of even one example in your experience where a self help technique wouldn’t have helped, then downgrade the usefulness of the technique, or at least register it as a data point (“oh, it works for a limited set of situations, might not work for situation X”) which would inform your eventual test of it.

You may then apply this to an author’s entire body of work. If too many of their techniques fail your backtests, you may reject the rest of their work, because it’s unlikely that they have techniques powerful enough for your use case. I find Tony Robbins and Rhonda Byrne to be particularly useless in this regard; I don’t read anything by them for this reason.

Why Even Read Self Help?

In his memoirs, Asian tycoon Robert Kuok writes:

Each successful businessman must develop his own formula. You must have it in you. I don’t believe a man can become a successful businessman merely by reading books. I think it’s better to observe the falling leaves than to read someone else’s advice. I was influenced by what I saw as shrewdness on Father’s part and some of the very human qualities in his human relationships. Mother was wise and made a great impression upon me. But, no one else really influenced me. In fact, in everybody else I saw weaknesses first, and I learned through the reverse mirror. If I observed their weaknesses, I made up my mind never to be like that.

This is a common observation, most often expressed as “book smarts vs street smarts”. I’ll tackle this conundrum in another post, but let’s consider the question “is it ever worth it to read self help?”

To answer the question, it’s useful to consider the extreme scenario: that all advice is useless, and that our experience is the best teacher.

If you reject this premise, then it reduces our question to: “self-help is a lousier form of getting advice, poorer than meeting believable people and asking them for it.”

Framing the question this way exposes the contours of the problem. I belong to the “your experience is the stupidest way to learn something; it’s much better to learn from other people’s mistakes” camp. You don’t need advice if your life is infinitely long, and if you can run unlimited trial and errors. But we don’t live forever, and most of us don’t have the resources for unlimited trial and errors. So advice matters.

I think taking advice is a useful skill in itself. You need to approach advice critically, and test each technique in your life to unmask the biases of the advice-giver.

I apply the same set of techniques that I’ve described, above, to each piece of advice I receive personally; perhaps this is what makes reading self-help useful to me.

Self help is merely a way of taking advice from people I’ve never met.

Update: I've posted a follow up to this post — Surprising Implications of Treating Self-Help as Art, which covers six surprising implications to this post.

If you want to see this in action, watch Jacob Collier in conversation with Herbie Hancock in this video. ↩︎

As a former competitive Judoka, I've experienced this pain first hand. Ugh. ↩︎

Though if the person giving the self help advice is believable enough, or if you have multiple sources giving the exact same piece of advice, then maybe there's something wrong with your practice of the technique. Caveat emptor. ↩︎

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→