Any discussion about fast adaptation in response to uncertainty should probably begin with John Boyd and the OODA Loop.

Boyd was an air force colonel who originally came to prominence as an ace fighter pilot (or an ace pilot instructor — depending on who you asked) at the Fighter Weapons School at Nellis Air Force base. His contributions spanned the length of his career and varied from fighter tactics to plane design to military strategy; I won’t go into all of them in this essay, and anyway you can get a good overview of the arc of his life over at Boyd’s Wikipedia page. Amongst other things Boyd developed the first fighter-tactics manual of the Air Force, the Energy-Manoeuvrability theory of aircraft performance, and a general strategic framework of acting under uncertainty that has no particular name, but is often referred to as a cluster of ideas of which the most prominent is ‘The OODA Loop’.

It is this final thing that is of interest to us.

Boyd is not without controversy. In the New York Times review of Robert Coram’s hugely entertaining biography of the man, Ronald Spector writes:

Nevertheless, Coram sometimes tends to minimize some of the real difficulties, aside from conservatism and bureaucratic inertia, in trying to put Boyd's war-fighting ideas into practice. It is easy to say that a military commander should always keep his enemy off balance by doing the unexpected, but frequently that commander may find himself with a unit that cannot do even the expected. The men may be inexperienced, unfamiliar with the terrain, half-trained, unused to operating together, inadequately armed and so on.

Napoleon wrote marginalia in some of the military books he read: ''Ignorance. . . . Absurd. . . . Absurd. . . . Impossible. . . . False. . . . Bad. . . . Very Bad. . . . Absurd.'' Few famous generals have been so obliging. Consequently, influence, or lack thereof, is usually hard to assess. Generals, like many other people, often claim to have read things they only wish they had read or do not remember what they actually did read. In the case of Boyd, who wrote no books or articles, the task becomes even harder. Coram makes several claims about Boyd's influence on the Army's AirLand Battle doctrine during the 1980's, on Cheney, then defense secretary, and on the gulf war. But it will probably be years before anyone can properly assess these claims. In the meantime, younger soldiers could do a lot worse than make themselves familiar with one of the most unorthodox and stimulating military thinkers of the last century.

Spector’s review includes these reservations because much that is written about Boyd is either hagiography or criticism; you may find several vicious treatments of the man if you Google deeply enough. (The most prominent example is probably USAF Chief of Staff General Merrill McPeak, who said: “Boyd is highly overrated (…) in many respects he was a failed officer and even a failed human being”). This should not come as a surprise — Boyd was not liked by many in the military establishment during his lifetime, and his personal failings left holes large enough to fly F-16s through.

On the other hand, Boyd continues to be regarded as a major figure in certain circles of military strategy. Frans Osinga’s book on Boyd’s ideas opens with the following paragraphs:

Some regard Boyd as the most important strategist of the twentieth century, or even since Sun Tzu. James Burton claims that ‘A Discourse on Winning and Losing will go down in history as the twentieth century’s most original thinking in the military arts. No one, not even Karl von Clausewitz, Henri de Jomini, Sun Tzu, or any of the past masters of military theory, shed as much light on the mental and moral aspects of conflict as Boyd.’ Colin Gray has ranked Boyd among the outstanding general theorists of strategy of the twentieth century, along with the likes of Bernard Brodie, Edward Luttwak, Basil Liddell Hart and John Wylie, stating that:

John Boyd deserves at least an honorable mention for his discovery of the ‘OODA loop’ . . . allegedly comprising a universal logic of conflict. . . . Boyd’s loop can apply to the operational, strategic, and political levels of war. . . . The OODA loop may appear too humble to merit categorization as grand theory, but that is what it is. It has an elegant simplicity, an extensive domain of applicability, and contains a high quality of insight about strategic essentials. . . .

Because so much of Boyd’s work is about fast adaptation in the face of uncertainty, I thought it might be fruitful to mine his work for ideas. I’m not entirely sure what I think of the overall theory — part of me thinks that it is trite, but another part of me thinks that it gets at something deep and fundamental about survival in uncertain, competitive, adversarial situations. At any rate, it is too early to pass judgment on Boyd, because I have not yet attempted to apply his ideas. But I do like a large number of things in his work, and I think there’s some merit to keeping Boyd’s ideas at the back of your head.

Boyd’s ideas are deceptively simple. A great number of blog posts about the OODA loop miss the point entirely. This is a first attempt at synthesising what is most interesting and useful in his work, and compressing as much of that down to a single essay.

Strategic Theory Is ‘Useless’

Boyd’s ideas are problematic for a number of reasons. Let’s talk about the most obvious one first.

Let’s imagine that you are a military thinker, and that you served in some of the most prestigious command positions in the most important wars of your era. Your goal is to write a treatise of strategic theory that is general enough to apply to any age. How do you do this?

A military thinker from Alexander The Great’s day would write about sword and shield and arrow. But that would be useless when applied to the trench warfare of WW1. Similarly, a military thinker from WW1 would write about trench warfare, and find his ideas useless when confronted with the technological advancements that made Blitzkreig possible in WW2. A military thinker from WW2 would write about the technical and organisational innovations that made Blitzkreig possible, and miss out on the implications of nuclear power that shaped so much of the Cold War strategic doctrine. And so on so forth; a military thinker stuck in the ‘mutually assured destruction’ world of US-Soviet competition would have little to offer us when faced with the guerrilla warfare tactics of Vietnam, the intelligent, unmanned weapons platforms that characterises so much of modern drone warfare, and the emerging era of great power competition that seems to lie at the core of modern US-China conflict.

The point is this: the exact contours of military strategy are always determined by the geopolitical realities and the technological capabilities of the day. If you are a military thinker and you want to write a strategic framework that stands the test of time, you would have to predict every geopolitical development and every technological breakthrough in history, because what is useful in one era is often not transferable to another. This is an impossible task.

The alternative, of course, is to climb the ladder of abstraction and detail only the most general, abstract principles that do not change over time. These principles will then act as guardrails as you develop specific new strategies that best fit your particular situation. This is what Boyd did. And this is why it is so challenging to parse and use his ideas — the more general and abstract an idea is, the more work you will have to do to get it to work for you.

Let’s put this another way, and reformulate the challenge through the language of business.

Every decade or so, a new set of dominant strategies evolves in business. Certain business leaders stumble upon (or spot, or discover by trial and error) changes in the larger environment that enable new business strategies; they execute those strategies and crush the competition. Smart management consultants and business professors will then begin to notice the existence of these strategies by observing the carcasses of dead or dying competitors left in the wake of the winning company; they begin to sniff around the actions and the utterances of the winning company’s management team in order to mine for insights. Eventually, some mix of consultant or business professor groks the essence of the strategy, the same way that a military analyst might finally come to understand Alexander the Great.

At this point, the idea-industrial complex whirs into work: the management consultants will turn the strategy into a set of cookie-cutter recommendations and sell it to competitors in adjacent (or even not-so-adjacent!) fields; the business professors will race to write papers and books to be sold to the management masses.

This marks the beginning of the end of the effectiveness of the strategy. As more competitors learn the specifics of the winning approach, they either begin to adopt the strategy for themselves or learn to counter the strategy (if at all possible). This then makes the winning strategy less effective. Eventually, these practices are taken into account in the actions of its competitors, and the dynamic of action-reaction stabilises into something that becomes the new business normal.

That is — of course — until a new set of business leaders stumble onto some other new strategic insight, and then the cycle starts all over again.

There are exceptions to this cycle. Hamilton Helmer’s 7 Powers: The Foundations of Business Strategy is a notable entry in this genre: Helmers writes about how certain business strategies are more defensible than others. 7 Powers is a book about moats, about how certain sources of power allow companies to gain a sustainable competitive advantage and defend their businesses against the rest of the market; these moats are things like building a brand, engaging in regulatory capture, or using network effects to lock out the competition.

But there is a reason that competitive moats are described as ‘quantitatively detected but qualitatively created’ — no amount of analysis will lead you to the sorts of insight necessary to get to that defensible position in the first place! In other words, moats are always built as a result of strategic savvy — I can tell you that having a powerful brand leads to sustained pricing power, but I cannot tell you how to build a powerful brand in your specific industry, in your specific circumstances, given competitors who are equally savvy, watchful of your actions, have access to the same playbook that you have, and are equally aware of the importance of brand as you are.

Long term readers of Commonplace would note that this describes the ‘metagame’, something I’ve written about in the past. The existence of a metagame implies that the real question when it comes to strategic thinking is how to adapt to the metagame faster than the competition — not necessarily how to understand or even use the strategy that won the last game. But of course, real world strategic thinking is a lot more complicated than the artificially constrained tactical considerations that are found in games; this is the reason it is still interesting to read thinkers like Boyd.

There is a secondary implication here. If the valuable bit of strategy is coming up with what is novel and unexpected to your adversaries, then reading about strategy isn’t as useful as you might think — or at least, not if your goal is to apply some existing strategy to your unique circumstances. The publication of a specific strategy often changes the environment necessary for the strategy to work — or at least triggers the countdown to the eventual demise of the effectiveness of that strategy. This is the problem that sits at the root of all strategic thinking: it is not enough to learn the strategies of the last war. The right question to ask in the face of a dynamic system of competition is the following: how do you become the sort of organisation or person who is able to come up with new strategies in the first place?

In 1975, on the eve of his retirement, Boyd began to ask questions that lay at the heart of this topic. One of the first questions he asked was: “As a fighter pilot, fast adaptation against the opponent leads to a kill. Does this apply across all levels of warfare?” And then: “How does one become the type of strategic thinker who is able to come up with new manoeuvres, designed to confuse the opponent, adapted for the current battlefield?” If you look at this question through the lens of business, the question takes on the form of: “How does one become the sort of business leader who is able to out-adapt the competition, confuse them, and by so doing continue to stay ahead of everyone else?” Because wars are fought by organisations, not individuals, Boyd then asked: “What do fast adapting organisations look like? And finally, because workable strategies are by definition novel and unexpected, Boyd realised that all the questions he had asked could be reduced down to: “where do new ideas come from?” and “what is the essence of creativity, really?”

The OODA Loop

Boyd’s best known idea is the OODA loop. We shall begin there.

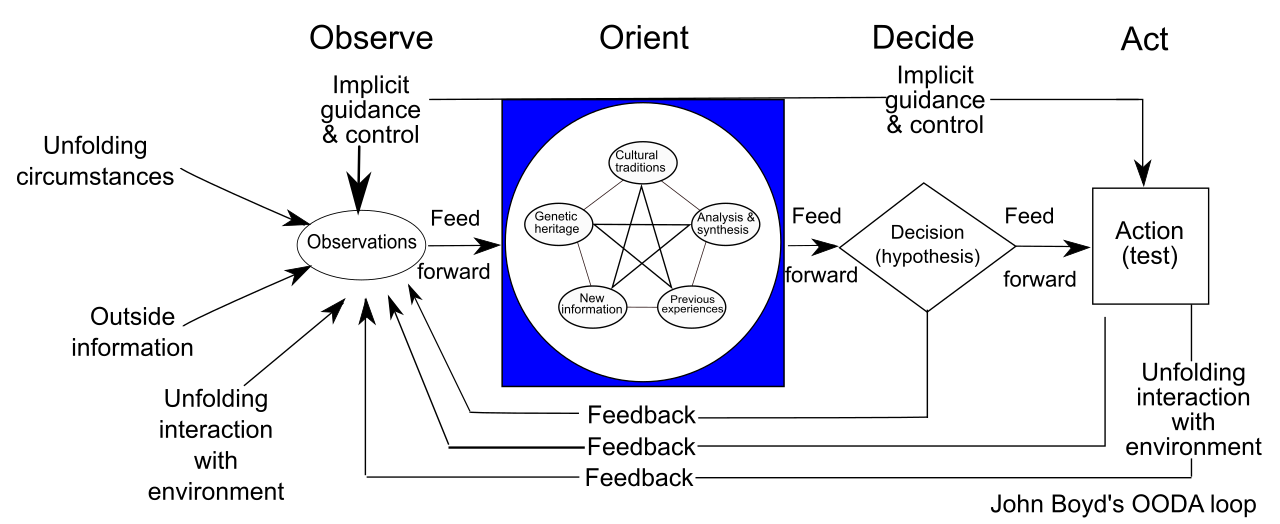

The OODA loop is simple to state: all humans act by Observing their environment, Orienting within it — that is, organise the messiness of reality in their heads by generating mental models or generate pictures of the situation, perhaps by using a framework from a business school if they are intellectually compromised — Decide a course of action, and then Act on it.

By itself, the OODA loop is not particularly interesting. As a decision making model, it is not backed by research, there are no descriptions of the exact mental mechanisms that humans use to execute this loop, and there is very little you can do with it if you think about it alone. In truth, however, Boyd meant it only as a common-sense description of how humans decide and act. If the OODA loop is obvious to you today, then all is good, but any rigour we have around the model is only because we have a body of work from the field of Naturalistic Decision Making to confirm that this is indeed how humans make decisions in the real world. (I’ve written about that field of research here).

I have always been annoyed by the pop-sci version of the OODA loop. The usage of the OODA loop in such circles usually goes like this: in times of uncertainty, you need to go through the OODA loop faster than the competition. Observe more! Orient better! Decide quickly! Then act! Then repeat everything again!

This is a bit like the pedagogically challenged coach who stands at the side of a track and yells at athletes “RUN HARDER, RUN FASTER” — which is funny to watch and possibly motivating. But it is not that useful. You shouldn’t need a fancy model to drive home the message “be decisive!”, and yet many business people deploy the idea of the OODA loop in only this fashion.

Thankfully, Boyd didn’t stop at the OODA loop. He merely used it as a starting point for a number of vastly more interesting ideas.

Idea 1: Looping Speed

The first idea is that a unit that goes through the decision cycle faster than the competition will defeat the competition. This is a rather trivial observation, and was in fact one of the earliest and most obvious of Boyd’s ideas. This notion of ‘out-looping’ the adversary fell out from Boyd’s observations that Korean-War-era F-86 fighter pilots in bubble canopies could orient themselves in 3D space better than the MiG pilots (who had forward facing canopies), so it was easier for the F-86 pilots to observe the MiG pilots than it was for his enemy to observe him. This — along with the F-86’s hydraulic controls — made for a distinct advantage against the MiGs of the era; Boyd theorised that the two features explained the asymmetric kill ratio between the F-86 and the MiG whenever the two planes met, despite the MiG’s theoretically higher manoeuvrability.

This first idea generalises easily, as it should: Boyd argued that it applied to armies battling under uncertainty, to businesses competing to death in winner-take-all markets, to organisations engaging in any sort of adversarial competition and also to organisms attempting to adapt to environmental change.

This leaves us with the question of “how does one go through the decision cycle faster than one’s opponents?” but we’ll come to that soon enough.

Idea 2: Mess With The Adversary’s Loop

The second idea is more interesting than the first. Boyd argued that because all humans operated using OODA loops, if you could get within an enemy’s OODA loop and screw with it, you would bring about a state of confusion and hasten him to his death.

What did Boyd mean by this?

The OODA loop that we’ve discussed so far has been a simplification. In reality, orientation is far more important when compared to all the other components of the loop. This is a roundabout way of saying that the stages of observing, deciding, and acting are implicit, instantaneous actions — we do them without much thought, and we do them so quickly that it might as well be wrong to call this a loop; much of what happens is all happening at the same time.

This leaves us with orientation, and it is orientation that is key. Therefore it follows that it is our enemy’s orientation that we must focus on if we want to fuck them up.

The diagram above is Boyd’s representation of the OODA loop. Notice how similar it seems to the Recognition Primed Decision Making model from the field of Naturalistic Decision Making. Humans (and by implication organisations) observe unfolding circumstances, gather outside information, watch the unfolding interaction of actions with the environment, and then organise these observations into something that makes sense in their heads. Humans then decide and act based on the results of their sensemaking.

Orientation is awfully important to grok, so I want to spend a few minutes talking about it.

I’ve mentioned before that humans are sensemaking beings, and that we abhor raw information being poured into our brains. In most cases, our sensemaking takes on the form of generating a narrative that ties together facts and observations into a cohesive whole that we can understand. Other times, we build a mental model of the situation (in the Jean Piaget sense, not the Charlie Munger sense) before we know how to decide and how to act.

This is not a new idea. Here’s philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn, for instance, in Revolutions As Changes Of World-View:

Surveying the rich experimental literature from which these examples are drawn makes one suspect that something like a paradigm is prerequisite to perception itself. What a man sees depends both upon what he looks at and also upon what his previous visual-conceptual experience has taught him to see. In the absence of such training there can only be, in William James’s phrase, “a bloomin’ buzzin’ confusion.” In recent years several of those concerned with the history of science have found the sorts of experiments described above immensely suggestive.

And you can find many more similar observations in other fields, which basically all say the same thing: how you orient or sensemake affects what you observe, and vice versa.

Boyd in particular breaks the orientation step down into five components:

- Your genetic heritage — because nearly all psychological traits show significant and substantial genetic influence (Plomin et all, 2017)

- The cultural tradition that you come from — which shapes your worldview.

- The previous experiences that you’ve had — which is the basis of expertise.

- The new information you are receiving from observing the environment, and finally

- Your ability to analyse and synthesise the observations you are receiving with the other factors above.

(That last bit on analysis and synthesis is incredibly important to other parts of Boyd’s theory, so we shall return to it in the next section.)

Here is the core insight, however: Boyd noticed that if you are able to overwhelm your opponent’s ability to orient under uncertainty, your adversary will ‘fold into himself’ — that is, be paralysed into fear and inaction. If it is an organisation that you are fighting, then this effect will take on the form of infighting amongst the various departments of the organisation.

In other words, you know you have started to win when you observe the enemy turning inward instead of outwards. If your adversary stops to introspect, to ‘take stock’ of what is going on — and you do not — then you know you have successfully disrupted his decision cycle; similarly, if your adversary is an organisation and you know that the various departments are arguing over what to do, you know you are close to destroying them.

How do you do this? Boyd lists three ways:

- You may speed up your execution tempo, thus overwhelming your adversary’s ability to orient himself under the deluge of new information generated by your actions.

- You may disorient your enemy, by acting in a sudden, unexpected, forceful way. (Boyd called such manoeuvres ‘fast transients’, as a throwback to his pilot days; fast transients referred to specific dogfighting manoeuvres where a pilot dumped energy or changed position violently, in order to gain an advantage on an adversary. Such fast transients would usually create a moment of complete disorientation in the opposing pilot, followed by death).

- You may disrupt your enemy by getting inside his OODA loop — that is, understanding his orientation — and therefore mislead him by presenting him with false impressions that reinforce the mental model he is building of the unfolding situation around him. The larger the gap between his sensemaking and reality, the easier it is to disrupt him later.

This is why the OODA loop is more interesting than first meets the eye. As a model of individual decision making it is simplistic and uninteresting. But as a model of an adversary’s decision making, the OODA loop offers us levers we may use in order to mess with them and win.

Idea 3: Beware Mismatches With Reality in Our Own Orientation

A useful idea that falls out of the adversarial lens we’ve used above is: “how the hell do you prevent this from happening to you?” And on this question, Boyd concentrates heavily on the idea of analysis and synthesis.

Why does he do so? Recall that there are five elements to the orientation step. Of the five, three are things that you have no control over (your genetics, cultural influence and your experiences), and one of them (new information that you receive through observation) is affected by your overall orientation. That leaves us with analysis and synthesis as a lever to focus on.

(This is not exactly true — as Gary Klein and his peers have shown, there is a lot that can be done with past experiences, as past experiences determine the pattern matching abilities that lie at the heart of expertise. Much of Naturalistic Decision Making is obsessed with developing effective training programs for marines and other military units, in order to improve their sensemaking abilities when they finally arrive on the battlefield. But Boyd spends no time at all on this part of orientation; his theory is nearly all principles, zero prescriptions).

Boyd believed that analysis and synthesis lay at the heart of good strategic thinking (and, really, at the heart of all good thinking). Here he is in Destruction and Creation, the only essay he ever wrote about his theories:

“There are two ways in which we can develop and manipulate mental concepts to represent observed reality: We can start from a comprehensive whole and break it down to its particulars or we can start with the particulars and build towards a comprehensive whole. Saying it another way, but in a related sense, we can go from the general-to-specific or from the specific-to-general. A little reflection here reveals that deduction is related to proceeding from the general-to-specific while induction is related to proceeding from the specific-to-general. In following this line of thought can we think of other activities that are related to these two opposing ideas? Is not analysis related to proceeding from the general-to-specific? Is not synthesis, the opposite of analysis related to proceeding from the specific-to-general? Putting all this together: Can we not say that general-to-specific is related to both deduction and analysis, while specific-to-general is related to induction and synthesis? Now, can we think of some examples to fit with these two opposing ideas? We need not look far. The differential calculus proceeds from the general-to-specific—from a function to its derivative. Hence is not the use or application of the differential Calculus related to deduction and analysis? The integral calculus, on the other hand, proceeds in the opposite direction—from a derivative to a general function. Hence, is not the use or application of the integral calculus related to induction and synthesis? Summing up, we can see that: general-to-specific is related to deduction, analysis, and differentiation while specific-to-general is related to induction, synthesis, and integration.”

(It goes on for quite a bit longer, Boyd was apparently a better orator than he ever was a writer; this is why reading Boyd is so incredibly difficult).

The core of this idea is that there are really only two modes of thought when you are sensemaking. You either take a framework and apply it to a situation, organising the facts to fit your desired narrative (analysis/deduction), or you take the facts as they are and build up an cohesive explanation for why they are the way they are (synthesis/induction). Anyone who has spent any amount of time writing a college term paper would be familiar with these two modes of thought.

Boyd argues that a smart strategic thinker (and a smart thinker … of any kind, really) must do both.

The reasons for this is simple: adversarial competition of any kind is a dynamic system between multiple actors. The very instant you form a mental model of the situation, you will make decisions and take actions, and therefore change the situation that you have observed. Getting stuck with one conception of the battlefield is a surefire way to be overtaken by the natural uncertainty of war (or be taken advantage of by a savvy enemy who is able to exploit your now static orientation).

Instead, Boyd argues that good strategic thinkers are able to destroy their mental models, and then recreate them either via analysis or synthesis, and repeatedly cycle through these two modes of thought as new information presents itself.

In the words of defense analyst Robert Polk, the objective of Idea 2, above, may be restated as follows:

Boyd believes that one's objective should be to act in a manner which destroys an adversary's ability to see reality (destruction of a domain or breaking the whole into its respective constituent elements) before he can collect linking elements to recreate a new and improved observation (creation of new perceptions of reality through specific to general induction, synthesis, and integration of common qualities or attributes found in the chaotic world).

As it is with war, so it is with rapid adaptation under uncertainty. If you have no ability to predict the future, then the next best thing is to leave yourself open to new information, and then reorient yourself repeatedly when faced with an uncertain, constantly changing environment.

Books about Boyd spend a great deal of time talking about Boyd’s snowmobile illustration, so let’s take a few seconds to talk about that. Boyd includes the snowmobile illustration in a couple of his briefings in order to demonstrate the principles of Destruction and Creation in action. He tells listeners to imagine a skier on a slope, a speedboat, a bicycle and a toy tank. He then asks listeners to break each example into component parts (for instance, imagine the skier on a slope as a collection of objects: the skis, the slope, chalets, chair lifts, and so on). After doing this for each domain, he pulls together skis from the skier, the outboard engine from the speedboat, chains from the bicycle and tank treads from the toy tank, and synthesises them into a ‘new reality’ — a snowmobile.

Cue applause.

You should not be surprised by this illustration if you are familiar with the Candle Box Problem or the psychological concept of Functional Fixedness (Wikipedia describes this as a ‘cognitive bias that limits a person to use an object only in the way that it is traditionally used’; go read the page, it’s full of fascinating examples). Boyd’s point is simply that the type of thinking that leads to creative problem solving of the candle box variety is the same type of thinking that is necessary to come up with novel strategies for a particular domain.

I find the snowmobile example rather overused in various articles and books about Boyd, and would have much preferred it if the authors simply referenced functional fixedness and used that as an illustrative example. But then, the majority of these writers came from military backgrounds and aren’t necessarily the types who would cite cognitive psychology; such is the price for having a thinker emerge from the oral briefing culture of the USAF.

Idea 4: Building Organisations That Can Orient Quickly

Boyd’s theory includes a significant component about group-level applications of the OODA loop (which makes sense: Boyd was a strategic thinker speaking to military men; a theory with nothing to say about command and control would be of very little use indeed). The question he settles on is this: how is it possible for a group to simultaneously sustain a rapid pace and with continued adaptation to changing circumstances without losing cohesion or coherence of their overall effort?

In this, Boyd was heavily influenced by German Blitz operating philosophy.

Blitzkrieg operating philosophy solves this problem by giving lower level commanders the freedom to shape or direct their own activities, while at the same time acting within a larger Schwerpunkt, or ‘strategic objective’. This allows the lower-level commanders to exploit the faster paced decision cycle available to them at the tactical level, while at the same time acting in harmony with the slower rhythm associated with the larger effort at the strategic level.

To achieve this, Boyd argued that you need to meet a number of organisational design goals.

The first is that there should be absolute trust in the subordinates’s ability to pursue the Schwerpunkt. This often expresses itself as an implicit contract between superior and subordinate. Boyd explains:

The subordinate agrees to make his actions serve his superior’s intent in terms of what is to be accomplished, while the superior agrees to give his subordinate wide freedom to exercise his imagination and initiative in terms of how the intent is to be realised. As part of this concept, the subordinate is given the right to challenge or question the feasibility of his mission if he feels his superior’s ideas on what can be achieved are not in accord with the existing situation or if he feels his superior has not give him adequate resources to carry it out.

The second is that the group’s communication should be as implicit as possible — that is, the individuals that make up the units share a common outlook and approach to tactical affairs. This makes communication easier, and group orientation faster. In WW2, this was achieved by having a body of professional officers who had received exactly the same training during the years of peace, with (per WW2 Blitzkrieg General Gunther Blumen-tritt): “the same tactical education, the same way of thinking, identical speech, hence a body of officers to whom all tactical conceptions were fully clear.” Blumen-tritt continues: “Blitzkrieg presupposes an officer training institution which allows the subordinate a very great measure of freedom of action and freedom in the manner of executing orders and which primarily calls for independent daring, initiative and sense of responsibility.”

It’s worth thinking about how this might look like if you took this sort of operational philosophy and applied it to, say, business. Presumably, what falls out would look something like Amazon (two-pizza teams executing at the periphery on new business initiatives, with only a loose set of rules to guide them) or Koch Industries (decentralised subsidiaries that operate with no budgetary control, but are instead evaluated on long-term return on invested capital; individuals are granted decision-rights in accordance to their abilities. Every employee is indoctrinated with the language of Market-Based Management, in order to guarantee a common outlook).

On that note, Boyd argued that a common outlook was the most important component of an organic, decentralised C2 structure. Boyd writes: “without the common outlook, superiors cannot give subordinates freedom-of-action and maintain coherency of ongoing action (…) these are a grouping of qualities that when acting together improve the ability to minimise one’s own friction through initiative at the lower levels harmonised by a shared vision of a single commander. To maximise the opponent’s friction, one must attack with a variety of actions executed at the greatest possible rapidity”

The end goal of these organisational design guidelines was something Boyd called ‘implicit guidance and control’. Such a command structure would enable (and again Boyd quotes Blumen-tritt here): “rapid concise assessment of situations, quick decision and quick execution, on the principle: ‘each minute ahead of the enemy is an advantage’.”

What to Think of Boyd?

I’ve left out elements of Boyd’s work that I think are of less interest to readers of this blog. Amongst them are Boyd’s conception of the three types of warfare (physical, mental and moral), his analysis of guerrilla warfare vs manoeuvre warfare vs attrition warfare, and his discussion about isolation vs interaction in adversarial competition. There are also ongoing debates about his legacy on the US military, various discussions about the practicality of manoeuvre warfare in the modern era, and the impact of his ideas with regard to the military reform movement … but I’ve left those out for obvious reasons.

What do I make of Boyd? This is really difficult to say. So much of Boyd’s theory exists at the level of first principles. This makes it difficult to evaluate, because first principles are several layers removed from practical application. I’ve spent the entire first section of this essay explaining why this is unavoidable — that strategic thought necessarily has to be general if it is to have any hope of being applied across eras. But this fact does not make the evaluation of Boyd’s ideas any easier.

What makes things trickier is that I’ve spent a lot of time on Commonplace writing about the dangers of chasing ideas from non-practitioners, especially when they have not been proven via actual application. I urge people to evaluate ideas against a hierarchy of practical evidence, and to downgrade the writing of less believable people. When applied here, Boyd’s ideas don’t fare very well — they live at the lowest level of practical evidence admissible by my hierarchy: that of plausible argument.

What gives me pause is that Boyd’s ideas make sense. They are common sense syntheses of some very useful concepts, organised in the service of combat. More importantly, they are consistent with my experiences with adversarial competition in the domain of business. But the man himself has demonstrated nearly no application of those ideas — in fact, his life reads a little like a self-aggrandising bureaucrat who took on the military establishment to reform it … and lost, again and again, never really adapting to his failures or learning from his mistakes.

(For those of you who familiar with Boyd and are quick to say that Boyd’s ideas led to the victories of the 1991 Gulf War, it is perhaps useful to Google some of the criticisms of these claims. I’d start here, but there are many, many others. I’ve read enough now to think that it is not at all clear if Boyd’s ideas were responsible for the Gulf War victories; at any rate, I don’t really care — I am only interested in Boyd to the degree that I may use his ideas for my goals. His legacy is for other commentators to decide).

Charles Koch likes to say: “true knowledge leads to effective action.” Because Boyd’s briefings and theories are so rarely prescriptive, it is difficult to say if they actually do lead to effective action.

I like what I see, and I think the odds are good that his ideas work. But I’ll have to find ways to test them to figure that out.

Appendix: John Boyd Reading Program:

- As always, start out with stories: Boyd by Robert Coram is a rollickingly good read, but is basically a hagiographic treatment that portrays the man as larger-than-life. Grant Hammond’s biography: The Mind of War: John Boyd and American Security is less effusive in its praise, but still remarkably positive (I’ve only skimmed Hammond's book; I read Coram’s book in its entirety). Treat both as on-ramps to become familiar with the context around the man’s ideas.

- What you really want to get to is Frans Osinga’s Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd. This is a heavy read, but contains all that is necessary to understand Boyd’s theories. Osinga even includes summaries of the major scientific influences and philosophical debates of Boyd’s day, which make for very tedious reading. If you’re familiar with that context, you may jump to the meat of Boyd’s ideas by reading Chapters 1, 5, 6 and 7, and skip Chapters 2 through 4.

- I found Chet Richard’s Certain to Win useful for understanding Boyds’s ideas about operational theory (Idea 4 in the essay, above) but otherwise thought that it was a rather disastrous attempt at applying Boyd’s ideas to business. Competing Against Time is more useful, albeit solely focused on time-based competitive strategy in the late 80s/early 90s. I have to say that Competing is a perfect example of a strategy book that renders a strategy less useful by the very nature of its existence. It is still worth reading, though; it bears the distinction of being Tim Cook’s favourite business book.

- Of the papers that I read about Boyd, I found Chet Richards’s paper Boyd’s OODA Loop (It’s Not What You Think) and Robert Polk’s A Critique of Boyd Theory — Is It Relevant to The Army? particularly useful. Polk’s monograph has a nice section on the effect of Boyd’s ideas on US military doctrine in the years since his death, and comments on Boyd’s theories with regard to Gary Klein’s work on the Recognition Primed Decision Making model; Richards’s paper is better than his book — he explains in concise terms why the simplistic form of Boyd’s OODA loop is stupid and worth tossing in the trash. Richards was also the first indication to me that there was more to the OODA loop than meets the eye, and for that I am grateful.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Market topic cluster, which belongs to the Business Expertise Triad. Read more from this topic here→