This is Part 4 of a series of posts on putting mental models to practice. In Part 1 I described my problem with Munger’s approach to mental models after I applied it to my life. In Part 2 I argued that the study of rationality is a good place to start for a framework of practice. We learnt that Farnam Street’s list of mental models consists of three types of models: descriptive models, thinking models concerned with judgment (epistemic rationality), and thinking models concerned with decision making (instrumental rationality). In Part 3, we were introduced to the search-inference framework for thinking, and discussed how mental models from instrumental rationality may help prevent the three errors of thinking as prescribed by the search-inference framework. We also took a quick detour to look at optimal trial and error through the eyes of Marlie Chunger. In Part 4, we will explore the idea that expertise leads to its own form of decision making. This is where my views begin to diverge from Farnam Street’s.

Many experts, in many fields, don’t do the sort of thinking we have explored in our previous part. They don’t do rational choice analysis. They don’t do expected utility calculations. They don’t adjust for biases, they don’t do appropriate search-inference thinking and they don’t use a ‘latticework of mental models from other fields’ to draw inferences.

And yet, despite a lack of grounding in the ‘best practices’ of decision science, they appear to perform remarkably well in the real world.

So what do they do?

They do recognition-primed decision making.

Recognition-primed decision making (henceforth called RPD) is a descriptive model of decision-making: that is, it describes how humans make decisions in real world environments. RPD is one of the thinking models from the field of Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM), which is concerned with how practitioners actually make decisions on the job. NDM researchers eschew the lab and embed themselves in organisational settings, and take an almost anthropological approach to research. They follow firefighters on calls, sit in tanks during military exercises, and interview interface designers and programmers in the office, during work tasks. The way the researchers do this is to use an interviewing technique they call Cognitive Task Analysis, which is designed to draw out tacit mental models of expertise.

NDM is interesting to us because it represents an alternative school of thought to conventional decision analysis. The growth of the cognitive biases and heuristics research program has created a number of prescriptive models — rooted in expected utility theory — designed to help us make more ‘rational’ decisions. We’ve covered the basics of that approach in Part 3. But the cognitive biases and heuristics program has also sucked up a lot of attention in recent years. We continually hear endless stories about the fallibility of human judgment and the errors and biases that systematically cloud our thinking. Whatever popular science books have to say about NDM is limited to the sort of ‘magical intuition’ as portrayed by Malcolm Gladwell in Blink.

This is a terrible portrayal. Because expert intuition is often portrayed as ‘magical’, we ignore it and turn to more rational, deliberative modes of decision making. We do not believe that intuition can be trained, or replicated. We think that rational choice analysis is the answer to everything, and that amassing a large collection of mental models in service of the search-inference framework is the ‘best’ way to make decisions.

It is telling, however, that the US military uses RPD models for training and analysis of battlefield decision-making situations. The field of NDM arose out of psychologist Gary Klein’s work, done in the 90s, for the US Army Research Institute for the Behavioural and Social Sciences. In the 70s and the 80s, the US Government had spent millions on decision science research — that is, on conventional models rooted in rational choice analysis — and used these findings to develop expensive decision aids for battle commanders.

The problem they discovered was that nobody actually used these aids in the real world. The army had spent ten years worth of time and money on research that didn’t work at all. It needed a new approach. (Chapter 2, Gary Klein, Sources of Power).

How Experts Make Decisions

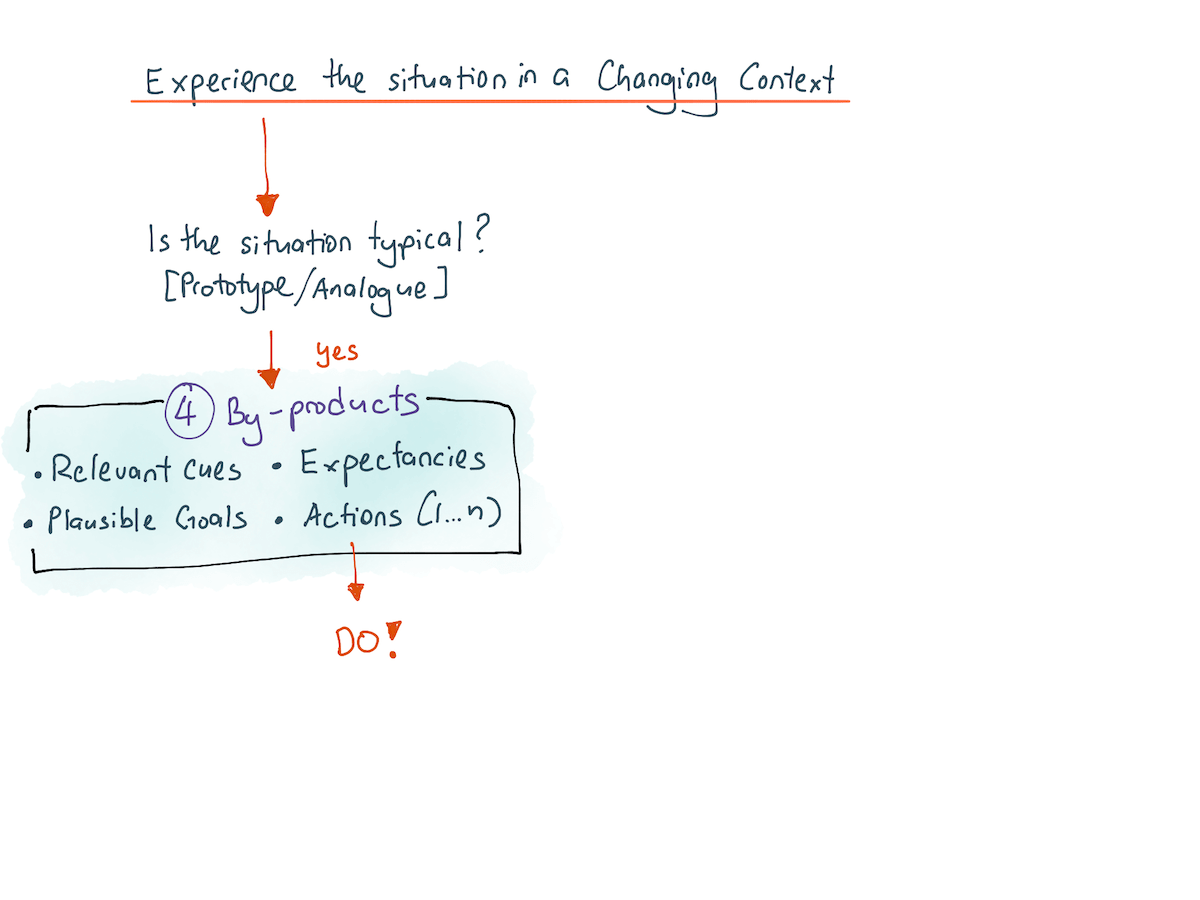

RPD describes the decision making that emerges from expertise. This is a huge differentiating factor; the majority of results in classical decision science was built on behavioural experiments performed on ordinary people. The model goes as follows:

Let’s say that an expert encounters a problem in the real world. The first step in the RPD model is recognition: that is, the expert perceives the situation in a changing environment and pattern matches it against a collection of prototypes. The more experience she has, the more prototypes or analogues she has stored in her implicit memory.

This instantly generates four things. The first is a set of ‘expectancies’ — the expert has some expectations for happens next. For instance, in a firefighting environment, an experienced firefighter can tell where a fire would travel, and how a bad situation might develop. An experienced computer programmer can glance at some code and tell if the chosen abstraction would lead to problems months down the road. A manager can hear two pieces of information during lunch and predict production delays two months in the future.

The second thing this recognition generates is a set of plausible goals — that is, priorities of what needs to be accomplished. In a life-or-death situation, a platoon commander has to prioritise between keeping his troop alive, getting to advantageous cover, and achieving mission objectives. His recognised prototype instantly tells him where his priorities lie in a given situation, freeing cognitive resources to conduct other forms of thinking.

The third thing that is generated is a set of relevant cues. A novice looking at a chaotic situation will not notice the same things that the expert does. Noticing cues to evaluate a changing environment is one of the benefits of experience — and it is necessary in order to prevent information overload. Think of driving a car: in the beginning, you find yourself overwhelmed with the number of dials and knobs and mirrors you have to keep track of. After a few months, you do these things intuitively and notice only select cues in your environment as you drive.

Last, but not least, a sequence of actions is generated by the expert, sometimes called an ‘action script’ — and it presents itself, fully formed, in the expert’s head.

The fact that RPD depends so much on implicit memory means that this entire process happens in a blink of an eye. Consider how you might recognise a person walking into the room as your friend ‘Mary’ or ‘Joe’. Facial recognition is an implicit memory task: the information ‘magically’ makes itself known to you. Similarly, an expert confronted with a work-related problem will perform the recognition and generate the four by-products instantaneously. When initially interviewing firefighters, Klein’s researchers found that the firefighters would often assert that they were not decision making: instead, they arrived at the scene of a fire and knew immediately what to do.

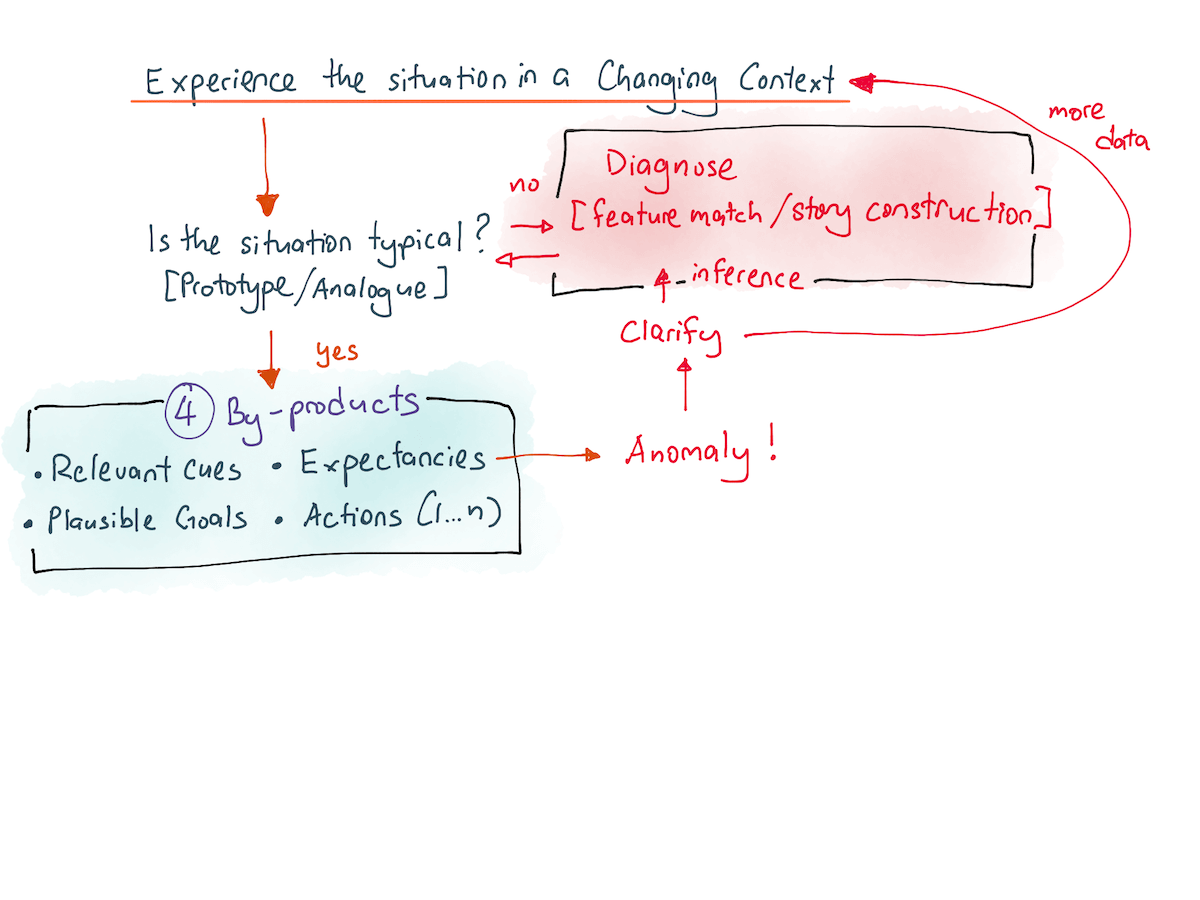

This is, of course, not a complete picture. What happens when the situation is unclear, or when the initial diagnosis is flawed? Here’s a story from Sources of Power to demonstrate what happens next:

“The initial report is of flames in the basement of a four-story apartment building: a one-alarm fire. The commander arrives quickly and does not see anything. There are no signs of smoke anywhere. He finds the door to the basement, around the side of the building, enters, and sees flames spreading up the laundry chute. That’s simple: a vertical fire that will spread straight up. Since there are no external signs of smoke, it must just be starting.

The way to fight a vertical fire is to get above it and spray water down, so he sends one crew up to the first floor and another to the second floor. Both report that the fire has gotten past them. The commander goes outside and walks around to the front of the building. Now he can see smoke coming out from under the eaves of the roof. It is obvious what has happened: the fire has gone straight up to the fourth floor, has hit the ceiling there, and is pushing smoke down the hall. Since there was no smoke when he arrived just a minute earlier, this must have just happened.

It is obvious to him how to proceed now that the chance to put out the fire quickly is gone. He needs to switch to search and rescue, to get everyone out of the building, and he calls in a second alarm. The side staircase near the laundry chute had been the focus of activity before. Now the attention shifts to the front stairway as the evacuation route.”

Where were the decisions here? The firefighter sees a situation — a vertical fire — and immediately knows what to do. But a few seconds later, he cancels that diagnosis because he recognises a different situation, and orders a different set of actions.

In rational choice theory, the firefighter is not making any decisions at all because he is not comparing between possibilities. He is simply reading the environment and taking action. Klein and co argue that decisions are still made, however: at multiple points in the story, the firefighter could have chosen from an array of options. The fact that he merely considers one option at each decision point doesn’t mean he didn’t make a decision — it is simply that he considers his options in linear fashion, finds the first that is satisfactory, and then acts on it.

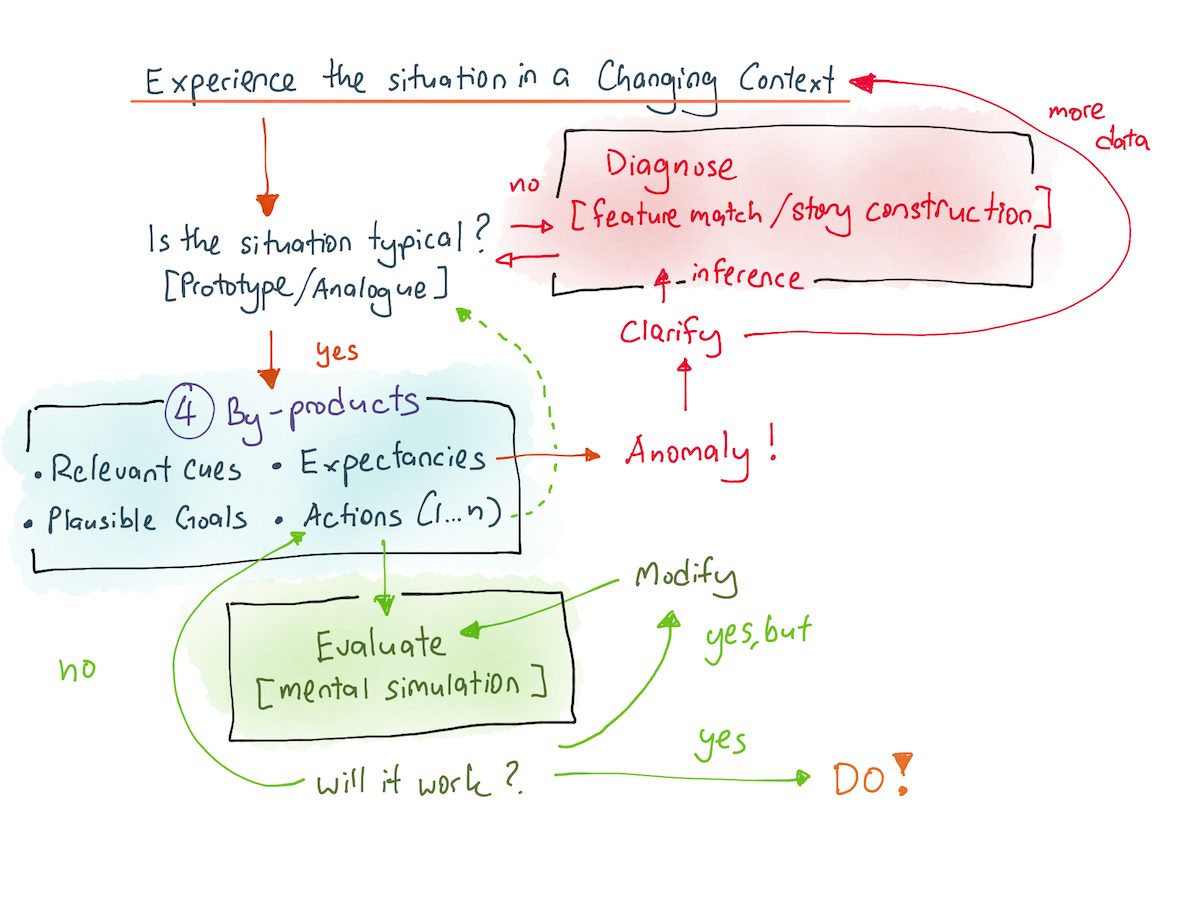

There are two conclusions from looking at this process. The first is to conclude that when we make decisions, we naturally look at our options one at a time. It just so happens that the first option an expert practitioner generates is often good enough for her goals. In many real world situations, it doesn’t matter that you arrive at the best solution — Herbert Simon argues that the ‘administrative man’ strives to find the first solution that satisfies a set of goals and constraints, instead of searching for an optimal solution to a problem. He calls this process ‘satisficing’; that is certainly what is happening here.

But even so, with enough practice in a ‘regular’ field (like chess), it is possible for this process to arrive at optimal or near-optimal decisions. When Klein and his team studied grandmasters, they found that most of them examined options one at a time, and engaged in comparison with a second option only in a minority of instances. However, the bulk of their decisions were still considered to be close to optimal.

The second conclusion we may draw is to say that our tendency to consider only one option at a time leaves us open to the first type of failure in the search-inference framework of thinking: that is, that we fail to conduct proper search. This is a good point, and RPD presents an explanation for why thinking failures affect us so systematically. But Klein points out that if you are in a field where you can build expertise, the answer isn’t to learn better deliberative decision making skills that slow things down — instead, the answer is to go out and build expertise of your own.

At any rate, we need to update the RPD model to include diagnosis. At the first step of RPD, prototype recognition generates a set of expectancies — things that the expert expects to happen. When the expectancies are violated, the firefighter immediately goes back to prototype recognition.

Is this all there is? No, it isn’t. There is an additional, final part to this model, needed in order to explain expert problem solving: that is, the occurrence of novel, sometimes wildly creative problem solving. What happens in such situations? The answer is this: when a novel or complicated situation presents itself to the expert, the expert will generate a sequence of actions and simulate it in her head. If a problem with those actions emerges during the simulation, she would go back to the drawing board and redo the solution, this time with a different approach. This continues until the expert settles on a workable solution. If the expert fails to come up with a workable solution, she will then drop back to diagnosis — to see if she has missed something in her reading of the situation.

Our final RPD model now looks like this:

I should note that RPD is valuable to me for one other reason: that is, after a years-long search with the goal of self-improvement, I have finally found a usable model that captures the essence of expertise.

Heuristics as strengths, not weaknesses

Alert readers will note that in the hands of an expert practitioner, what are considered sources of bias in rational choice analysis are considered strengths in the RPD model.

The availability heuristic, demonstrated by Kahneman and Tversky in 1973, says that we bring what is immediately available in our working memories to bear on our thinking. In the lab, unsuspecting subjects rely on what is easily available to them to make judgments — leading them to make wildly wrong ones. In the real world, experts in regular fields draw from a large reservoir of perceptual knowledge to make quick, correct decisions.

The representativeness heuristic, again demonstrated by Kahneman and Tversky in 1973, argues that humans pick wrong representations on which to build our judgments. In the hands of novices, this heuristic leads them to make wildly wrong probability estimations. In fields with expertise, however, experts deploy the representativeness heuristic to quickly pattern match against prototypes and to pick the right environmental cues in evaluating a complicated, evolving situation.

Finally, Kahneman and Tversky’s simulation heuristic is used by experts to construct powerful explanatory models and to accurately simulate the consequences of their actions. Both require powerful stores of experience; novices asked to simulate the effects of actions in a dynamic environment often can’t do so. In Kahneman and Tversky’s work, the simulation heuristic is used to explain that people are biased towards information that is easily imagined or mentally simulated.

Is RPD an artefact of System 1 thinking, or an artefact of System 2 thinking? The correct answer is that it is both. The initial prototype recognition is a System 1 result, but the subsequent linear evaluation and simulation process is deliberative: System 2. That it uses Kahneman and Tversky’s documented heuristics is but an implementation detail. This doesn’t make RPD flawed, however. In fact, Klein’s approach is refreshingly different: he thinks that RPD captures how humans naturally think, and instead of using unnatural, explicit methods from decision science, he believes we should look for ways to build on what we already have.

Klein also argues that the cognitive heuristics and biases program is an incomplete picture: that is, it discounts the importance of expertise when making judgments and decisions. In fields where expertise genuinely exists, we should not fight against natural impulses like the one to generate stories. Instead, we should understand the strengths and weaknesses of each tool and use them accordingly.

In Kahneman’s defence, I should note that both he and Tversky have never said that heuristics worked badly. Instead, they have always argued that heuristics exist because they work well for a wide variety of circumstances. It is merely in our interpretations of their results that we seem to have forgotten this. In 2009, Kahneman wrote a paper with Klein on this topic, titled Conditions for Intuitive Expertise: A Failure to Disagree, in which the two describe the approaches of both of their fields, and elucidated the conditions under which which expert judgment may be trusted (or distrusted!).

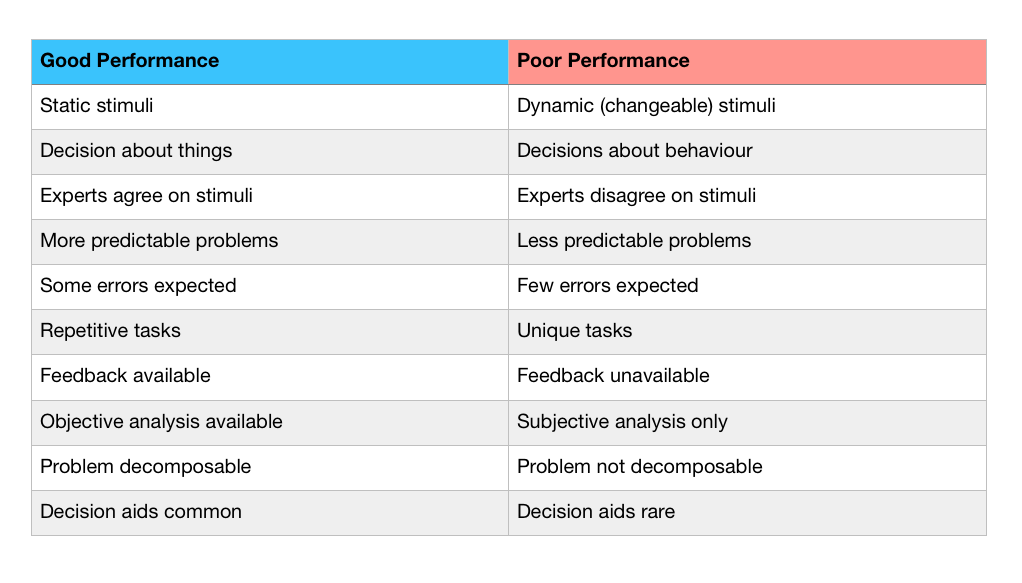

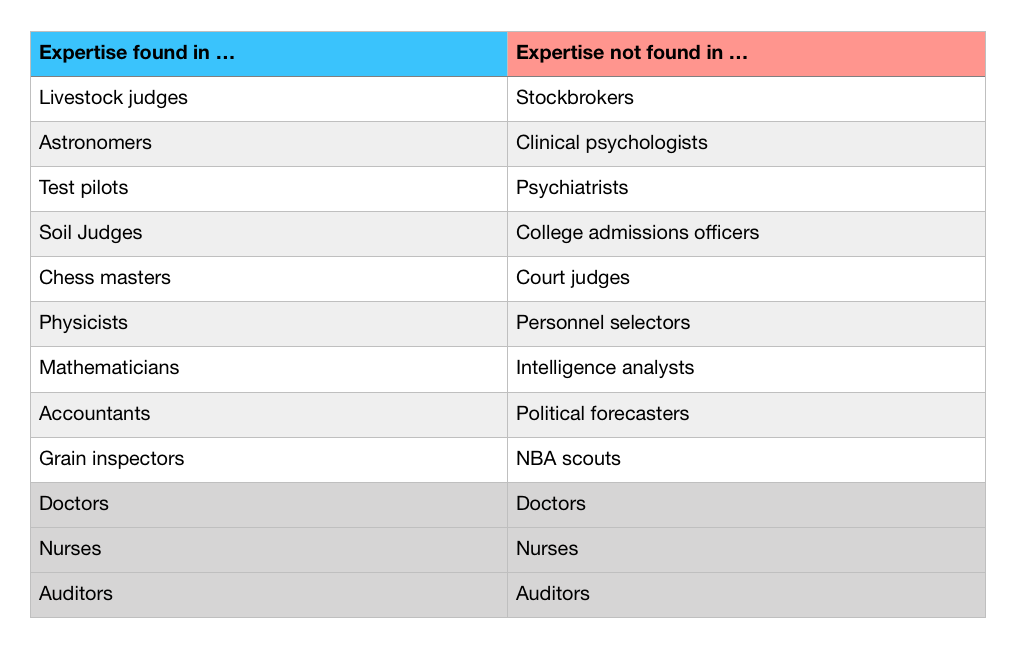

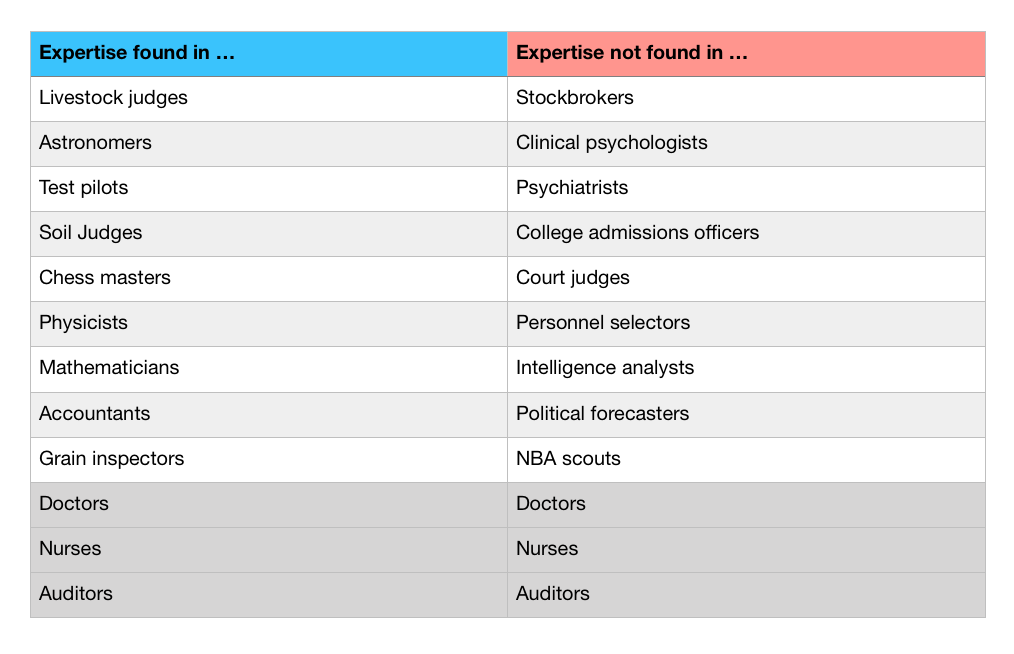

In this, they draw from Robin Hogarth’s, Anders Ericsson’s and James Shanteau’s research. Shanteau presents the following features in his paper on the conditions for expertise. (I’ve copied this table representation from Stuart Armstrong of LessWrong):

I should note, however, that Shanteau’s list of features represent properties that lie on a spectrum. Klein and co have examined various fields in which expertise exists alongside subjective analysis, dynamic stimuli, and even where ‘decisions about behaviour’ are expected. For this reason, Kahneman and Klein have reduced the requirements for expertise in their paper to only two points: first, that the field must provide adequately valid and regular cues to the nature of the situation, and second that there must be ample opportunities for learning those cues.

For example, firefighters operate in an environment of regularity — there are consistent early indications that a building is about to collapse. There are also consistent early indications that a premature infant is fighting an infection. Conversely, Kahneman, Klein and Shanteau all argue that stock picking is a highly irregular activity:

... it is unlikely that there is publicly available information that could be used to predict how well a particular stock will do—if such valid information existed, the price of the stock would already reflect it. Thus, we have more reason to trust the intuition of an experienced fireground commander about the stability of a building, or the intuitions of a nurse about an infant, than to trust the intuitions of a trader about a stock.

Earlier in this series I said that perhaps Munger’s approach to Elementary Worldly Wisdom works because the feedback loop from stock picking is more apparent than that of other fields. I see now that I am mistaken: rather, Munger’s recommendation to rely on rational decision analysis is borne out of the difficulties of building expertise in stock picking. In other words, expert intuition has little place in stock investing, and Munger is rightly concerned with proper decision-making tools as prescribed by Baron et all.

What other fields are implicated? In his 1992 paper, Shanteau noted the following list of professions (combined with a few more examples from Kahneman and Klein):

What should we conclude from these results? The immediately obvious view is that if you are in a field where the environment is irregular and where there are few opportunities for feedback, you should focus your skills on instrumentally rational mental models, as we have discussed in Part 3. You should protect yourself against the three errors of the search-inference framework, you should score yourself based on your decision-making, you should keep a decision journal and you should build your latticework of mental models.

But then consider the reverse of this idea: if you are not in a field like stock-picking, perhaps you should not do as Munger says.

How bad is deliberative decision making, really?

It’s worth pausing now to ask: why is it so important to build expertise in fields where expertise exist? Why can’t we just apply rational decision analysis to everything?

The answer is that deliberative decision-making, of the sort recommended by Farnam Street and Munger — is incredibly slow. Remember what Baron said in Part 3: “search is negative utility!” The search process that you have to perform using rational choice analysis is a very meticulous, explicit one. It guarantees a certain amount of negative utility every time that it is used.

In certain fields like firefighting, flying, or emergency medical care, rational choice analysis is not viable because of the time-sensitive nature of the field. But there are implications for us in other fields as well. In competitive fields where expertise exists, the person who stops to consider every decision will always be beaten by the expert who has developed intuitive mental models of the problem domain. The expert can rely on intuition to guide her search; the novice cannot.

Speed and accuracy of decision-making is not just one competitive advantage — it leads to many interrelated advantages. Klein and co document eight ways that experts outperform novices due to the depth of their tacit knowledge: they are able to see patterns that novices do not, they are able to notice anomalies that indicate events far earlier than less experienced practitioners, they have good situational awareness throughout problem solving processes, they understand deeply the interactions of things in their problem domain, they see opportunities and improvisations that others do not, they are able to simulate events in the near future or infer events that have happened in the recent past, they perceive differences that are too small for novices to detect, and they recognise their own limitations. (Sources of Power, Chapter 10)

In fact, in many cases, Klein notes that practitioners who engage in rational choice analysis in fields where expertise exists are novices, not experts. They have no choice but to do choice comparison because they do not know how to read the situation quickly and intuitively. A large part of his work has been to develop training programs to move novices away from deliberate decision-making — for he notes that if novice practitioners are never given the opportunity to train their intuitions, their rate of learning will be forever stunted.

Herbert Simon, who won a Nobel prize for his work on organisational decision making, also offers us another reason that rational choice analysis alone cannot provide optimal outcomes. Simon argues that decision makers are subjected to ‘bounded rationality’: that is, it is impossible to make any important decision by gathering and analysing all the facts. There are too many facts and too many combinations of facts. The more complex the decision, the larger the combinatorial explosion becomes.

Klein also points to research that is starting to pile up showing that decision making without expertise leads to bad outcomes; in Power of Intuition he says: “The evidence is growing that those who do not or cannot trust their intuitions are less effective decision makers, and that as long as they reject their intuitions, they are destined to remain so. Attempts to promote analysis over intuition will be futile and counterproductive.” Finally Klein notes with some satisfaction that the field of decision science is slowly coming round to a balance between expertise, bias avoidance and rational choice analysis.

The question now is what does this mean for us. Here the research presentation ends and the editorialising begins.

A Personal Take

I believe that most of us work in domains that have what Kahneman and Klein call “fractionated expertise”. (In the 2009 paper they state that they believe most domains are fractionated). Fractionated expertise means that a practitioner may possess expertise for some portion of skills in the field, but not for others. Kahneman and Klein write:

... auditors who have expertise in “hard” data such as accounts receivable may do much less well with “soft” data such as indications of fraud (…) In most domains, professionals will occasionally have to deal with situations and tasks that they have not had an opportunity to master. Physicians, as is well known, encounter from time to time diagnostic problems that are entirely new to them—they have expertise in some diagnoses but not in others.

This explains why doctors, nurses and auditors appear on both sides of Shanteau’s list:

Kahneman and Klein note that good physicians often have the ‘intuitive ability to realise the characteristics of the case do not fit any familiar category and call for a deliberate search for the true diagnosis’. That is, they know when to switch from RPD to rational choice analysis.

The most powerful lesson from their joint paper is that in fields with fractionated expertise, it is incredibly important to recognise where one has expertise and where one does not. The confidence produced by expert intuition will feel equally strong in cases where you have real expertise, and in cases where you do not. But that doesn’t negate the need for developing expertise in the first place.

What does this have to do with my practice? Well, I ran the software engineering for a small company in Singapore and Vietnam from 2014 to 2017. I believe that management and business is a domain with fractionated experience, because that squares up with my experience.

At my previous company, I was called to provide input on large client projects, or to discuss business strategy with my boss at certain points during the year. In these situations, we engaged in rational choice analysis, and took the time to adjust our inferences. But I noticed that in certain types of decision making, we seemed to get better with experience … in other types of decision making we did not.

In the day-to-day management of my engineering office, however, I became very competent at running my department in service of producing software for the business. I built mental models of management in the pursuit of this goal — by reading books, finding mentors, but most importantly by adapting recommendations into a series of tests that I applied to my slice of the company. Each time I failed, I gained some new understanding of the principles behind the technique, and why they might or might not apply to my unique situation. I also constructed good mental models of the inner workings on the company — again, mostly through trial and error. Eventually, I could predict potential problems between sales, engineering and customer support — often before people in those departments saw them. I cultivated information sources inside our growing company, modified small portions of the sales process when I saw it was starting to cause problems for engineering and customer support, and refined a hiring process I could codify and pass down. I became a valuable part of my boss’s operations; at the end of three years, we were making S$4.5 million a year in revenue, up from 300k two years before.

Note that in none of these situations did an understanding of Darwin’s theory of evolution or a grasp of thermodynamics helped me. What helped the most was building expertise; and expertise in management is not built by reading widely. It is built by practice: by breaking down techniques, applying them, and reflecting on the failures. It is built by finding mentors, asking them for advice tailored to your situation, watching how they think as they gave their recommendations, and then simulating their thinking while implementing that advice.

The mental models that were most important for my success was the mental model of my company, of the processes that produced results, of the information flow that might lead to misunderstandings, and — much later — of the overall lay of the land of our market in Singapore, and of the nature of our competitors. Once I possessed these mental models, I found I could navigate work-related problems effortlessly.

A small example suffices. Shortly after I hired our first HR exec, she asked what potential problems there might be within the engineering department. I paused for a moment, and then explained the team dynamics that were developing, the problems of miscommunication that would result from my hiring of a new team manager, the lack of engineering processes on one of the teams compared to the other and the consequences of that imbalance. I also explained what interventions I was performing to prevent some of these problems from worsening and my confidence (or lack of) in the likelihood of success of each of these interventions. The HR exec was impressed, but I was left with the conundrum of teaching her my internal mental models. I did not succeed.

This was when I began to suspect that something was wrong with Munger’s prescription.

Why was expertise and the building of tacit, personal mental models more important for me than building a latticework of general descriptive models? One possible answer, perhaps, is that at the bottom levels of most domains, deliberate decision-making matters less and expertise matters more. I was only rarely called to make strategic decisions; this changed as the company grew. I expect that as you rise, your ability to do good deliberative decision-making becomes more important.

That said, compare my story with that of Klein’s ‘friend’ (from the Power of Intuition, Chapter 1):

“Consider a former executive I know, a man who headed a very large organization. He was known for doing meticulous work. He rose through the hierarchy and eventually was appointed to run a division. And that’s when everyone realised that his meticulous attention to detail had a down side—he wasn’t willing to use his intuition to make decisions. He had to gather more and more data. He had to weigh all the pros and cons of each option. He had to delay and agonise, and drive his organization crazy. He never missed any essential deadlines, but his daily indecision sapped morale and made for lost opportunities. After a decade of mismanagement, he retired, to the relief of his colleagues and staff members. And then came the news—he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Fortunately, medical science has developed a range of treatments for prostate cancer. Unfortunately, patients have to make decisions about which treatment to accept. As I write this, more than ten months have elapsed since the diagnosis, and the former executive still hasn’t settled on a treatment. He is busy acquiring more data and assessing his options.”

Do you know someone like this? Conversely, do you know someone who is completely driven by intuition and gut feel — who makes decisions without analysis? How do you think this has turned out for them? What do you think is the right mix?

Trial and error, and the mystery of the Chinese businessmen

There is one final aspect to this. I mentioned in Part 2 that trial and error dominates as a problem solving strategy in ill-defined fields. I also opened Part 3 with a discussion of the failure modes of trial and error.

Here’s where we tie the two threads together. I think trial and error is how most of us will build expertise in our careers — a direct result of the lack of theory and insight for many practicable areas of interest. Even practitioners in areas with good theory — such as medicine, engineering, or computer programming — must spend a large amount of their time developing expertise through experience and practice.

Expertise happens to be the collection of approaches that Marlie Chunger keeps in his toolbox:

In this pursuit of building expertise we can choose to be systematic, or we can choose to be thoughtless. I’ve noticed that some really smart friends of mine don’t seem to learn good lessons from events they’ve experienced. Others continually learn new lessons by reviewing old experiences and decisions. Anecdotally, the latter seem to have less problems than the former.

I’ve also observed that I am not very good at selecting trials or learning lessons where emotions are involved — such as when I deal with people I find ‘difficult’. I’ve noticed that I regularly need to ask people for a second opinion when evaluating an experience, to adjust for blind spots. And I’ve noticed that I need to consciously vary my approach the next time a similar problem emerges.

I think there’s a lot to be said for applying the methods of instrumental rationality to the process of trial and error itself. At each stage of the trial and error process, do proper search-inference thinking to evaluate if

- There is a risk that you will blow up

- There is a reasonably good amount of information you can learn from the trial you are about to do if it fails

- There is a more generalisable lesson to be learnt

- There are salient features to recognise a similar problem in the future

How do you know that you are getting better? For this, I think we should look to what actual practitioners do. In Principles, Ray Dalio suggests that we may use the class of problems we experience in our lives to gauge our progress. That is, while you might not be able to evaluate the results of a trial and error cycle immediately, you may, over time, observe to see if the problems that belong to that class seem to become easier to deal with. If you find that problems in that class no longer pose much of a challenge for you, then you may conclude that your collection of ‘principles’ or approaches are working and that you have improved.

I’ve used this to great success in the years since I started applying Dalio’s ideas (I read an earlier, terribly formatted PDF version of his book in 2011). Dalio deals with most of the problems that one might encounter during a trial and error cycle. In fact, I’d wager that his methods provide an effective prescriptive model for instrumental decision making. He calls his approach to trial and error the ‘5 Step Process’ (Youtube video here).

As a final note, I think Klein’s RPD model and Taleb’s observation of the nature of trial and error gives us a plausible answer to the mystery of the ‘traditional Chinese businessmen’. My current hypothesis is this: if you are sufficiently rational in your trial and error cycles, and if you build expertise in a fractionated domain such as business, two things should eventually happen. First, the fractionated nature of business means that you would eventually build intuitions around the regularities in your domain — like hiring, retaining employees, evaluating deals, and negotiating with suppliers. Second, the nature of trial and error should eventually result in your success over a long enough period.

It doesn’t matter that each individual decision, examined in isolation, does not demonstrate the principles of good decision making. It is quite clear that traditional Chinese businessmen use intuition and ‘gut feel’ to guide their decisions — in some business domains this would work well, in others not so. But if they never break the cardinal rules of trial and error (that is, risk being blown up) — the convexity of their environment should eventually work out. They should eventually experience success.

Putting this together

So let’s finally put everything together. How do you put mental models into practice?

First, let’s talk about beliefs.

Are you a policy maker? Or are you interested in holding better, more accurate beliefs — especially beliefs that can’t be checked through personal experience? For instance, do you want to have properly considered opinions on topics such as: “climate change is real”, or “immigration is beneficial to the economy” or “capital punishment costs the state more than it benefits society”?

If you do, what you want to do is to improve your epistemic rationality. Read the thinking mental models related to evaluating beliefs and overcoming cognitive biases, and look up LessWrong for prescriptive models on how to overcome them. Then read widely, think deeply, and (as Shane puts it) do the work necessary to have an opinion on the issue.

Second, if you are interested in the practice of mental models for better decision making, then you must first ask: are you in a field that is conducive to expertise formation? Or are you in one that is so irregular that it may be considered wicked (as per Hogarth, 2001)? Or are you — like most of us — in a field with fractionated expertise?

If you belong to a field that is not conducive to expertise formation, then you should probably do as Farnam Street prescribes: keep a decision journal, use a checklist, build a latticework of mental models, and — as we know from Part 3 — avoid the three errors of good search and inference. You can’t evaluate a decision based on outcomes (because luck), so you should evaluate your decisions based on the thinking errors you detect in retrospect.

These methods also matter if you are going to make decisions that you have little expertise in. For instance, most of us won’t have expertise in choosing a life partner, picking a career, or choosing a good school to send our children to. In these kinds of decisions, proper deliberative decision making will probably help, as will a wider range of mental models.

That said, I think that everyone who is interested in decision making should pay attention to the nature of expert intuition. The adoption of intuitive decision-making as part of US military doctrine (in 2003) and the growth of NPD-based training programs for soldiers, nurses and firefighters is telling. The form of decision making that most of us do is recognition-primed decision making, not rational choice selection. We should pay close attention to what we actually use and figure out ways to improve it, instead of improving what we are told to use (but rarely do).

The core of my criticism of mental model education in The Mental Model Fallacy was that the most valuable mental models one can learn are tacit in nature. I asserted that these models are domain-specific, constructed from one’s reality, and built from practice, because practice is how you gain expertise, and because the types of knowledge that make up expertise are always tacit.

I do not believe that Munger and Buffett have zero expertise (and I doubt anyone would say so either!) But I also do not believe that Munger’s prescription of ‘reading widely and building a latticework of mental models’ is the sole reason (or even the primary reason!) for his success. I think that — even in the degenerate domain of stock picking, Munger and Buffett have fractionated pools of expertise — such as in rapidly analysing financial statements, in sizing up management teams, in judging partners, and in applying or developing decision-making tools for their investing.

I could be mistaken on this; I am in no way a Berkshire scholar. Let me know.

Next week, I want to turn my attention to building expertise. Specifically, I’d like to talk about the kinds of training methods that Klein and co have built to train RPD-based decision-making skills amongst soldiers, firefighters, and nurses. Experience is a great teacher when you’re building expertise, but it’s also a bad one because there are so little opportunities for it. So what do you do for training intuition in the absence of experience?

Let’s find out.

Go to Part 5: Skill Extraction

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→