This post is Part 2 of A Framework for Putting Mental Models to Practice. Read Part 1 here.

Any discussion about putting mental models to practice must begin with a discussion of rationality.

Why? Well, ‘rationality’ is the study of thinking in service of achieving goals. If we want a framework for putting mental models to practice, what better place to start than the academic topic most focused on applying tools of thought in the service of better judgments and decisions?

Rationality, however, is a loaded word. It brings to mind ‘rational’ characters like Spock from Star Trek, who are unable to express emotion adequately and who reason robotically. What exactly do we mean when we say ‘rationality’?

The best definition that I’ve found is Jonathan Baron’s, laid out in his textbook on the topic Thinking and Deciding: “rationality is whatever kind of thinking best helps people achieve their goals.” Note the implications of this definition, however: if your goal is to find love and live happily ever after, then rationality is the kind of thinking or decision making that is necessary for you to achieve that; if your goal is to destroy the planet, then rationality is whatever thinking is necessary for you to do so. Rationality has nothing to do with emotion, or lack thereof; it merely describes the effectiveness with which a person pursues and achieves his or her stated goals.

Rationality as defined like this is not unknown in the popular literature. Here’s Warren Buffett, in a 1998 interview in Fortune titled The Bill and Warren Show:

How I got here is pretty simple in my case. It's not IQ, I'm sure you'll be glad to hear. The big thing is rationality. I always look at IQ and talent as representing the horsepower of the motor, but that the output — the efficiency with which that motor works — depends on rationality. A lot of people start out with 400-horsepower motors but only get a hundred horsepower of output. It's way better to have a 200-horsepower motor and get it all into output.

Buffett’s conception of rationality as ‘effectiveness’ is not unique. There has been an organised attempt in recent years to quantify rationality, out of the belief that rationality explains how IQ alone isn't sufficient to explain success in life. This pursuit has led to the development of a ‘Rationality Quotient’, led primarily by the efforts of University of Toronto Professor of Psychology and Human Development Keith Stanovich. I’ll quote him as described by this Credit Suisse paper on RQ:

Keith Stanovich, a professor of applied psychology at the University of Toronto, distinguishes between intelligence quotient (IQ) and rationality quotient (RQ). Psychologists measure IQ through specific tests, including the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, and it correlates highly with standardized tests such as the SAT.

IQ measures something real, and it is associated with certain outcomes. For example, thirteen-year-old children who scored in the top decile of the top percent (99.9th percentile) on the math section of the SAT were eighteen times more likely to earn a doctorate degree in math or science than children who scored in the bottom decile of the top percent (99.1st percentile).

RQ is the ability to think rationally and, as a consequence, to make good decisions. Whereas we generally think of intelligence and rationality as going together, Stanovich's work shows that the correlation coefficient between IQ and RQ is relatively low at .20 to .35. IQ tests are not designed to capture the thinking that leads to judicious decisions. (emphasis mine)

Stanovich laments that almost all societies are focused on intelligence when the costs of irrational behavior are so high. But you can pick out the signatures of rational thinking if you are alert to them. According to Stanovich, they include adaptive behavioral acts, efficient behavioral regulation, sensible goal prioritization, reflectivity, and the proper treatment of evidence. (emphasis mine)

I include RQ in our discussion only because I find RQ to be a remarkably useful concept to have. When we say that someone is ‘effective’ at attaining their goals, or that they are ‘street smart’, what we really mean is that they are epistemically and instrumentally rational. RQ, IQ, and EQ also helps explain certain observable differences in humans: it explains, for instance, why smart people can be jerks, empathic people can believe in crazy things, and effective people can have average intelligence.

The Two Types of Rationality

Rationality is commonly divided into two categories. The first is epistemic rationality, which concerns thinking about beliefs. The second is instrumental rationality, which concerns thinking about decisions.

- Epistemic rationality is “how do you know what you believe is true?”

- Instrumental rationality is “how do you make better decisions to achieve your goals?”

When you say “I believe Facebook stock is currently undervalued”, you are engaged in the kinds of thinking epistemic rationality is concerned with.

When you ask “Which college degree should I study: computer science or economics?” you are engaged in the kinds of thinking instrumental rationality is concerned with.

We may now see that Farnam Street’s list of mental models is really a list of three types of models:

- Descriptive mental models that come from domains like physics, chemistry, economics, or math, that describe some property of the world.

- Thinking mental models that have to do with divining the truth (epistemic rationality) — e.g. Bayesian updating, base rate failures, the availability heuristic.

- Thinking mental models that have to do with decision making (instrumental rationality) — e.g. inversion, ‘tendency to want to do something’, sensitivity to fairness, commitment & consistency bias.

The vast majority of Farnam Street’s mental models are of the descriptive variety, as per Munger’s prescription in Elementary Worldly Wisdom, which means that they don’t naturally lend themselves to practice. As many in this learning community have pointed out, you can’t really put ‘thermodynamics’ to practice, say, in the way that you can put ‘bayesian updating’ to practice.

I’ll talk about the usefulness of descriptive mental models much later in this series. For now, I want to focus on the mental models that are the methods of thought — that is, epistemic rationality and instrumental rationality. Taken together, the promise of rationality training is incredibly attractive: that we may improve our thinking in order to achieve our goals — whatever our goals may be.*

*(Note: this is not a ridiculous claim to make: if we applied the methods of rationality to goal-selection itself, we would not pick unachievable goals.)

Putting Epistemic Rationality to Practice

One of the crowning achievements of modern economics and psychology is the Cognitive Biases and Heuristics research program created by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. In it, Kahneman and Tversky document the various ways in which human beings act ‘irrationally’ — that is, that they think and perform in ways at odds with what is rational.

When I began my search for a framework to improve my thinking, the cognitive biases research program appeared like a blinding billboard on the road to enlightenment. It seemed for awhile that a multitude of paths led to some cognitive bias or other. And indeed: a rich academic field of applied psychology, judgment and decision making has since sprung up around the findings from Kahneman and Tversky’s work; in 2002, they were awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics.

It’s no surprise, then, that the topic we call ‘epistemic rationality’ is in practice the study of methods and mental models to overcome the cognitive biases that Kahneman and Tversky have discovered. And the best place to hunt for such methods is a community blog by the name of LessWrong.

LessWrong was created in 2009 by writer and artificial intelligence theorist Eliezer Yudkowsky. Over the next five years the community developed into an enthusiastic group of thinkers, writers and practitioners, all dedicated to the search for better methods of thinking by way of overcoming bias. Their primary method for doing so was to mine the fields of applied psychology, economics and cognitive science for the latest findings on preventing bias; they then wrote up the findings for presentation to a wider audience and encouraged sharing of notes from putting these methods into practice. LessWrong is responsible, for instance, for popularising Bayesian updating, effective altruism, and the idea of rationality research itself. From its community comes bloggers like Scott Alexander and gwern, both of whom continue to write about related topics.

Here’s a small sample of such threads:

- The Cognitive Science of Rationality documents some of the findings LessWrong has aggregated over the first two years of its life. To see some concrete recommendations, jump to the section titled ‘Rationality Skills’.

- Fixing the planning fallacy simply demands that you compare your current project with the ‘outside view’, that is, to other projects that are superficially similar to yours.

- There are multiple treatments of Bayesian Updating, or ‘Bayesian Thinking’ on LessWrong. This introduction to the general modes of thought is worth reading. Here is a story illustrating Aumann’s Agreement Theorem, sadly also demonstrating the tendency for Yudkowsky and co to use long-winded stories while explaining their ideas. Here is some reflection by a forum member on what practicing Bayesian has taught him.

- I particularly enjoyed this explanation of the Shelling Fence — a concept designed to defend against slippery slope arguments, as well as hyperbolic discounting.

LessWrong’s approach makes up the first part of my framework for putting mental models to practice. Remember the second principle in my epistemological setup: when it comes to practice, one should pay attention to actual practitioners. In this case, LessWrong represents nearly nine years of putting cognitive bias prevention methods into practice. If you are interested in mental models that will help you refine your beliefs, then you should go to LessWrong and search for threads on topics of interest, and pay special attention to threads where people have put those methods to practice in their lives.

If you have the opportunity, you may also consider paying to attend a workshop conducted by the Center For Applied Rationality (or CFAR) — a non-profit organisation set up by LessWrong community members with the aim of teaching the methods of rationality to a general audience.

LessWrong has grown significantly less active over time, however. If you can’t find a LessWrong thread on a specific method you are interested in (or if you cannot attend a CFAR workshop), you would do well to adopt their original methodology: that is, diving into the academic literature on judgment and decision making to find methods to use.

In order to do this, however, you’ll need to understand the underlying approach in the field of decision making. Consider: what does it mean to have made ‘better’ decisions? How do you measure the concept of ‘better’?

The approach decision scientists have used to study this is to analyse thinking in terms of three models (Baron, Thinking and Deciding, Chapter 2):

- The descriptive model — the study of how humans actually think, a field of study that draws from the sort of investigative work that Kahneman and Tversky pioneered.

- The normative model — how humans ought to think. This represents the ‘ideal’ type of thinking that should be achieved. For instance, if we were studying decision making, this would be the ‘best’ decision one could take.

- The prescriptive model — what is needed in order to help humans change their thinking from the (usually flawed) descriptive model to the normative model.

For instance, ‘neglect of prior information’ is a cognitive bias — that is, a descriptive model of how humans naturally think. The normative model in this case is Bayes’s theorem. And the prescriptive model is Bayesian updating.

When searching for practicable information in the academic literature, then, you should focus your attention on prescriptive models. But you should understand that the prescriptive models are always developed in service of helping humans achieve the modes of thinking as defined in some normative model. The papers that describe prescriptive models will almost always give you the normative model at the same time. And here we face our first serious problem.

The alert reader might notice a gaping hole in my description of the decision science approach: “But Cedric!” I hear you cry, “How can one possibly know what the ‘best’ decision is in real life?!”

You, dear reader, have hit on the central problem of any framework for practice. In some situations, such as with errors of probabilisitic thinking, we have a clear normative model: that is, the theory of probability. (Alert readers will realise the descriptive model in this case is prospect theory — the theory that won Kahneman and Tversky the Nobel prize). Having a clear normative model allows us in many cases to check to see if our practice has made us better at thinking — that is, have gotten us closer to the normative model. But in many cases of decision making in real life, we have no way of knowing what the ‘best’ decision is.

(That is not to say that decision science doesn’t have normative models for good decision making. But I’ll explore the problems with those later.)

This is partly the reason why we are talking with epistemic rationality first — the normative models are clearer, the descriptive models are richer, and the prescriptive models to correct our thinking are easier to put into practice. A community of practitioners have sprung up around this topic. It is instrumental rationality that is the problem for our framework of practice.

It’s taken me four years to find a suitable answer to that question — three of which was spent building a small company in Singapore and Vietnam. I’ll talk about my answers in the next part to this series. But for now, let us look at LessWrong’s attempts to grapple with this problem.

LessWrong’s Mysterious Flaw

LessWrong was created in the pursuit of both kinds of rationality. The central premise of the site was that if you improve your mental models for understanding the world (epistemic rationality), you would make better decisions, and you would be able to ‘win’ at life — the LessWrong term for achieving your goals.

In September 2010, roughly a year into LessWrong’s life, Patri Friedman wrote a critique titled Self-Improvement or Shiny Distraction: Why Less Wrong is anti-Instrumental Rationality. In it, Friedman argued that this goal was a lie: LessWrong was primarily focused on improving methods at getting at the truth. This was separate from instrumental rationality — that is, the decision making ability necessary to achieve goals in one’s life.

LessWrong, Friedman asserted, consisted of people who were happy to sit around and talk about ‘better ways of seeing the world’ but were not so interested in actually doing things, or attempting to achieve real goals. It was, in other terms, a ‘shiny distraction’.

About three years later, respected community member Luke Muehlhauser observed that people like Oprah Winfrey were incredibly successful at life without the sort of epistemic rigour that LessWrong so prized.

Oprah isn't known for being a rational thinker. She is a known peddler of pseudoscience, and she attributes her success (in part) to allowing "the energy of the universe" to lead her.

Yet she must be doing something right. Oprah is a true rags-to-riches story. Born in Mississippi to an unwed teenage housemaid, she was so poor she wore dresses made of potato sacks. She was molested by a cousin, an uncle, and a family friend. She became pregnant at age 14.

But in high school she became an honors student, won oratory contests and a beauty pageant, and was hired by a local radio station to report the news. She became the youngest-ever news anchor at Nashville's WLAC-TV, then hosted several shows in Baltimore, then moved to Chicago and within months her own talk show shot from last place to first place in the ratings there. Shortly afterward her show went national. She also produced and starred in several TV shows, was nominated for an Oscar for her role in a Steven Spielberg movie, launched her own TV cable network and her own magazine (the "most successful startup ever in the magazine industry" according to Fortune), and became the world's first female black billionaire.

I'd like to suggest that Oprah's climb probably didn't come merely through inborn talent, hard work, and luck. To get from potato sack dresses to the Forbes billionaire list, Oprah had to make thousands of pretty good decisions. She had to make pretty accurate guesses about the likely consequences of various actions she could take. When she was wrong, she had to correct course fairly quickly. In short, she had to be fairly rational, at least in some domains of her life.

What is true of Oprah is true of many entrepreneurs I know.

You’ve probably watched Crazy Rich Asians, a movie about the super rich Chinese of Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. ‘Traditional’ Chinese businessmen are a cultural trope of the Overseas Chinese diaspora — a diaspora that I belong to. Earlier this year, I wrote a series of posts to reflect on my experiences working with and competing against such businesspeople. My central observation: while incredibly superstitious, these businessmen were often very good decision makers. The primary model for most successful Chinese businesses is that of a conglomerate: a single business controlling interests in a wide array of industries such as palm oil, shipping, hospitality, rice, flour, steel, and telecommunications. The first generation of Chinese businessmen had no formal education, and had to survive various challenges like Malaysia’s preferential race policies, and Indonesia’s Chinese genocide.

It’s difficult to believe that the best Chinese businessmen could achieve such success without being able to make thousands of good decisions across so many industries.

Why is this the case? One possible reason was the one given by Aaron Swartz: that LessWrong was too consumed with cognitive biases as presented by the literature, and not consumed enough by cognitive biases that mattered in real life. In simple terms, perhaps the sort of cognitive biases explored by Kahneman and Tversky were simply the most obvious ones — or the ones most easily measured in a lab. On LessWrong, Swartz wrote:

Cognitive biases cause people to make choices that are most obviously irrational, but not most importantly irrational... Since cognitive biases are the primary focus of research into rationality, rationality tests mostly measure how good you are at avoiding them... LW readers tend to be fairly good at avoiding cognitive biases... But there a whole series of much more important irrationalities that LWers suffer from. (Let's call them "practical biases" as opposed to "cognitive biases," even though both are ultimately practical and cognitive.)

…Rationality, properly understood, is in fact a predictor of success. Perhaps if LWers used success as their metric (as opposed to getting better at avoiding obvious mistakes), they might focus on their most important irrationalities (instead of their most obvious ones), which would lead them to be more rational and more successful.

Where Epistemic Rationality Matters

Were they — Swartz, Muehlhauser and Friedman correct? Is instrumental rationality more important to success than epistemic rationality?

Well … yes and no.

In some fields, epistemic rationality matters a great deal. These fields are the ones where getting things right are really important. Or, to flip that around, epistemic rationality matters in fields where getting things wrong are very costly: for instance, in finance, where a wrong, leveraged trade can cost you your firm, and in statecraft or government intelligence — where the wrong assessment might mean hundreds of deaths.

However, in fields where the cost of getting things wrong isn’t that high, another approach dominates: trial and error.

The mainstream thinker that best tackles this dichotomy is Nicholas Nassem Taleb. Taleb points out that in situations where the cost of failure is low but the potential upside is high, trial and error dominates as the optimal strategy. He says that some situations have ‘positive convexity’, and argues that in situations where you have such convexity, you are set up to benefit from randomness.

A few examples suffices to illustrate this concept. In business, an entrepreneur who is able to quickly and cheaply experiment has a higher chance of success. His downside is capped to the opportunity cost of time and the upfront capital necessary to start the business; the Lean Startup methodology reflects this reality by suggesting that entrepreneurs run quick and cheap experiments in the beginning in order to find a viable idea. In startup investing, each investment is downside-capped to the amount that the investor puts into the company. However, the upside is often 10x higher; the optimal strategy here is to make lots of little bets, in the hopes that one or two will pay for the costs of everything else.

When Naval Ravikant says, in his FS interview: “Basically, I try and set up good systems and then the individual decisions don’t matter that matter much. I think our ability to make individual decisions is actually not great” — this is what he means. When Taleb says “you don’t have to be smart if you have (positive) convexity” this is what he’s referring to.

Where Instrumental Rationality Matters

It’s worth it to take a step back and consider this from a broader perspective. Why is trial and error so effective at getting to success? And why do we need to be told this? A baby learning to walk or speak for the first time needs no instruction; he or she learns by trial and error. But we adults need thinkers like Taleb or frameworks like The Lean Startup to tell us to engage in rigorous trial and error.

To answer this question, I’m going to adapt a section I wrote in my Chinese businessmen series:

The answer, I think, lies in education.

Broadly speaking, there are two basic approaches to problem solving: trial and error, and theory and insight. It's difficult to overstate how much we are driven towards theory and insight by the formal education we receive.

Consider the problem of bridge building. The trial and error approach to bridge building would be to slap together a bunch of things until you find a design that works. Today, this approach is considered horrifying and is never used. We have since worked out the underlying physics of bridges, and have developed sophisticated tools to design them. Structural engineers can tell whether a design would work even before construction begins; an engineer who gets things wrong, in fact, would find himself shamed by society, and punished severely by the professional bodies in his industry.

And so we internalise: "trial and error is a stupid way to build bridges" and extend that. We think: "study hard in school; learn math, physics and engineering, and you will be able to save yourself from error."

Our education system prioritises learning from theory and insight. This seeps into other parts of our lives. Consider: when you have a decision to make, the bias of your education is to slow things down, to think things through, to look before you leap. It doesn't even cross your mind that failure might be the smart move. There is a straight line from the lesson about building bridges to your approach to decision making - you don't want to fail because failure is bad in 'theory and insight'. So you spend more time thinking than acting.

The good news is that thinking deeply and then acting is optimal for fields where a body of knowledge exists. It is also necessary for fields where the inherent cost of failure is high. But in fields where little is known, where failure costs can be made low, or where things change too quickly for theory to find handholds, trial and error dominates as the superior problem solving strategy. It dominates because it is faster: where the cost of failure is low, and iteration speed is high, each iteration allows you more information because it lets reality be the teacher.

In these fields, failure is an acceptable cost of learning. In these fields, thoughtfulness takes on a different form.

I believe that business is one such field. If you are an entrepreneur, the optimal strategy for learning in business is trial and error, because industries often change too quickly for there to be immutable and universal rules. The ‘traditional Chinese businessmen’ that dominate in South East Asia are thus the product of trial and error. They were not highly educated, nor did they go through academic-style epistemic rationality training. They engaged in trial and error and were rational enough to learn from it.

Taleb notes two important caveats to trial and error: first, you need to prevent yourself from blowing up. You can't trial and error if you go bankrupt, after all. Second, you need to be sufficiently rational when experimenting so that you do not make the same mistakes repeatedly. (And I will add a third injunction: Taleb’s model assumes infinite time; you also need to be sufficiently rational when picking trials instead of picking randomly, so that you don't die before you achieve success).

In a nutshell, Taleb is saying that the sort of rationality involved when engaged in trial and error is instrumental rationality. Here we have our first hints of an answer.

Conclusion

We will follow the hint presented by Taleb’s ideas in the next part of this series, in our search for a good answer to the normative problem I mentioned earlier. For now, I want to wrap up what we’ve covered in Part 2, and mention a few caveats.

The first caveat is that while I present epistemic rationality and instrumental rationality as two different things — in accordance to the literature — I don’t mean to say that they are unrelated. Even the most epistemically rigorous trader has to have some amount of instrumental rationality if she is to be successful at trading. Conversely, a business person needs to to be able to evaluate evidence properly in her domain if she is to make good business decisions, even with the benefit of trial and error.

The main purpose of separating the two in our discussion is to recognise that the approach for putting models to practice in each type of rationality differs. If you are in a field where getting things right is important, then it might be worth it to work through the list of cognitive biases and their corresponding prescriptive models as LessWrong has done. But if you are like me — in a field where instrumental rationality matters more — then … well, stick around for the ideas in the next two parts.

The second caveat is that — while I have presented nothing genuinely novel in this part, that is going to change in the near future. In Part 3, I will venture outside the field of judgment and decision making and will begin to make some assertions of my own. In so doing, I will draw from my own practice (that is to say, my experience in testing this framework). This is vastly less rigorous. I urge you to be patient with me; in a latter part I hope to present a full account of the epistemological setup I mentioned in passing in Part 1. In other words, I will give you a new way to evaluate my claims, aka I will hand you the rope with which you can hang me on my credibility.

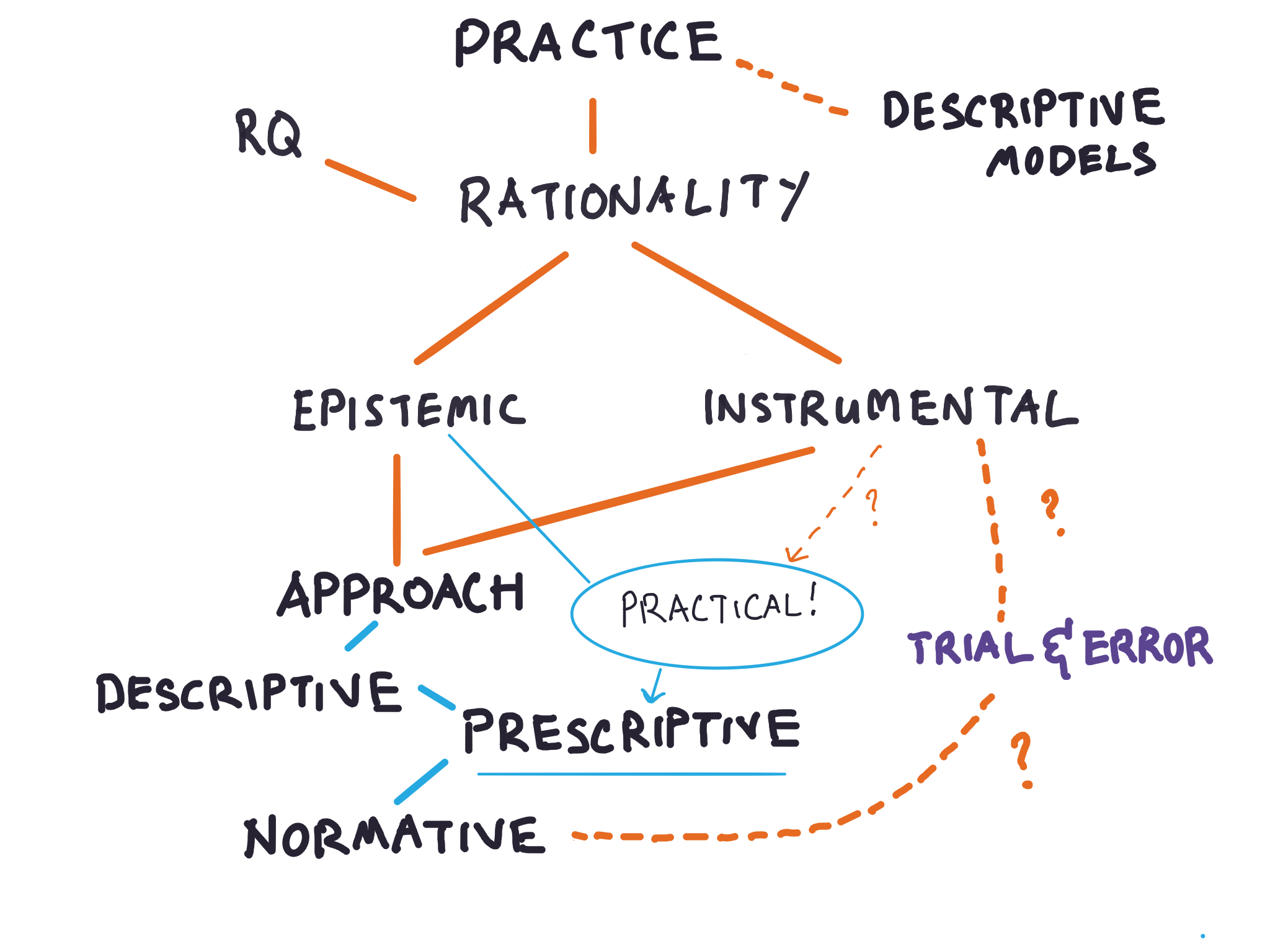

Alright, time to wrap up. Here’s a concept map of what we’ve covered so far:

First, I presented ‘rationality’ as the basis of structure for organising mental models. I explained how the study of rationality broadly splits the venture into studying ‘epistemic rationality’ and ‘instrumental rationality’. I argue that the list of mental models in Farnam Street belong to three different categories: descriptive models from other domains, thinking models that deal with epistemic rationality, and thinking models that deal with instrumental rationality.

I mentioned that the descriptive models might not be practicable, though we’ll discuss that later, once we touch on learning science (probably Part 4 or 5, I can’t tell yet).

I mentioned that the mental models in epistemic and instrumental rationality belong to a body of work that offers practicable methods, and gave you the underlying approach decision scientists use when presenting research on the topic so you may evaluate papers in the field yourself.

I also mentioned that epistemic rationality is far easier to start putting to practice, and that a community of such learners exist at LessWrong; they also have a non-profit, CFAR, dedicated to teaching such methods.

Next week, we’ll take a closer look at the normative problem brought up earlier in this essay: that is, “In decision making in real life, how do you know you’re getting better at making decisions? How do you know you are making the ‘best’ decisions?” In doing so, we will begin to move out of pure decision science, and into body of work around developing expertise. I’ll also explain what I’ve learnt from putting some of my ideas in practice, and what I think happens to be LessWrong’s big blindspot.

Go to Part 3: Better Trial and Error.

Originally published , last updated .