This is a summary of a bad ???? branch book. You should read this summary instead of reading the book; more specific recommendations follow. Read more about book classifications here.

If you open a random self-help blog or browse the self-help section in a bookstore today, odds are good that you’ll see a large section dedicated to habit design, or habit modification.

Ray Dalio himself writes, in Principles:

For a long time, I didn’t appreciate the extent to which habits control people’s behavior. I experienced this at Bridgewater in the form of people who agreed with our work principles in the abstract but had trouble living by them; I also observed it with friends and family members who wanted to achieve something but constantly found themselves working against their own best interests.

Then I read Charles Duhigg’s best-selling book The Power of Habit, which really opened my eyes. I recommend that you read it yourself if your interest in this subject goes deeper than what I’m able to cover here.

The reason habits holds such a special place in the self-help literature is because a large percentage of our decision making and behaviours are habits in disguise. We don’t engage in explicit and thoughtful decision-making for the vast majority of our lives — instead, we execute what is routine, operating at a level below conscious thought.

Charles Duhigg’s 2012 book The Power of Habit purports to explain how this works.

The problem with Duhigg’s book, however, is that it possesses a Malcolm Gladwell-level of rigour. Duhigg is a journalist, formerly of the New York Times, and has no science background to speak of. He opens The Power of Habit with a fantastic first section on habit formation and the underlying neuroscience (assuming he got even that right) … and then proceeds to stretch one’s credulity in the following two sections, where he attempts to explain organisation culture and societal behaviour through the lens of habit formation.

It’s telling that the keystone idea of the book — that habits are formed in a trigger, routine, reward loop — vanishes in the second and third portions of the book, as Duhigg struggles to explain group behaviour through the lens of individual neuroscience. He has to pretend that group psychology and organisational psychology — lenses better suited to explaining group behaviour and organisational routine — doesn't exist ... a formidable task for any intellectually honest writer.

Still, Duhigg is a good storyteller, so the book remains entertaining throughout. But you’re probably better off reading the first section of the book, and then jumping to the appendix at the end to read about changing existing bad habits. Everything else is fluff designed to give Duhigg a career in corporate speaking engagements.

This is a comprehensive summary — you can read this post instead of reading what is frankly a lousy branch book. In fact, I'll go further: read this post instead of reading the book — and then apply for a slot in Behavioural Scientist BJ Fogg’s free Tiny Habits course. You’ll get more actionable value out of that than reading the entire book.

The Core Idea

The core idea that Duhigg has to offer is that habit formation happens in a loop:

- You receive a trigger.

- You act out a routine.

- You receive a reward.

This is a fairly well-established finding in the behavioural design literature; Duhigg explains that this habit formation loop exists because the brain attempts to conserve mental power whenever possible — and habit formation is one key way to doing so.

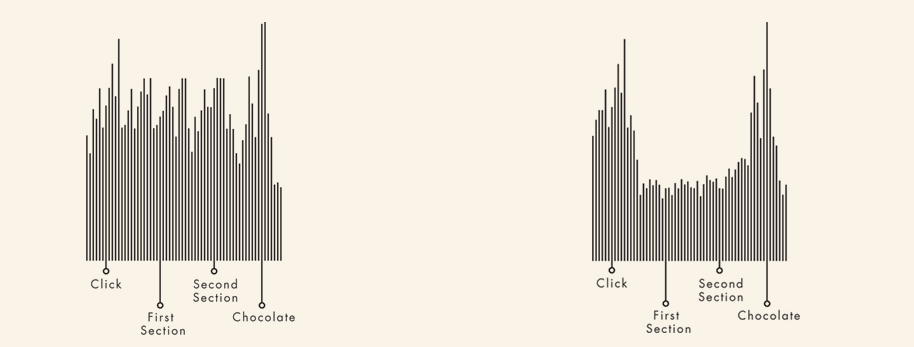

The way the brain does this is to find a trigger and a reward, and to use the trigger and reward as signals to hand off execution to a stored routine. Duhigg describes an experiment by a team of MIT neuroscientists, where the scientists stuck a probe into a lab rat’s basal ganglia, and then placed the rat in a maze with a bar of chocolate at the end.

On the first run, the rat’s brain displayed consistent activity throughout its exploration of the maze. But as time wore on, the rat’s brain displayed a peak of activity only during the start of the maze — where a click signalled the rat’s release — and the end, when the rat found the chocolate.

Duhigg then asserts that our routines are governed by similar neurochemistry, and are similarly mindless. Consider, for instance, if you spend any thought on what you’re actually doing when you’re in the shower, or what you’re doing when you brush your teeth in the morning.

The most compelling story in this section is the story of Eugene Pauly — a man who lost all short-term memory due to a bout of viral encephalitis in 1993. Pauly’s ability to function despite losing a portion of his brain — to go home, eat, dress, sleep, and act normally in social situations — was due to the habit formation abilities of his basal ganglia, which remained intact. Duhigg writes:

One day, (Professor Larry) Squire asked Eugene to sketch a layout of his house. Eugene couldn’t draw a rudimentary map showing where the kitchen or bedroom was located. “When you get out of bed in the morning, how do you leave your room?” Squire asked.

“You know,” Eugene said, “I’m not really sure.”

Squire took notes on his laptop, and as the scientist typed, Eugene became distracted. He glanced across the room and then stood up, walked into a hallway, and opened the door to the bathroom. A few minutes later, the toilet flushed, the faucet ran, and Eugene, wiping his hands on his pants, walked back into the living room and sat down again in his chair next to Squire. He waited patiently for the next question.

Eugene Pauly’s story becomes the centrepiece with which Duhigg illustrates the pervasive power of habit. It’s a compelling story because it appears so horrific: we cannot imagine living without short-term memory. But it is also effective; it makes you wonder at the extent to which habit governs your own behaviours.

Craving and Behavioural Modification

The second idea that Duhigg offers us is the relationship between the habit loop and our addictions. Duhigg explains that our execution of good and bad habits are driven by an expectation of the reward that lies at the end of the habit loop. This creates a craving — and the craving explains why we keep eating junk food, or remain enmeshed in bad behaviours against our better judgment.

Duhigg spends a good portion of the first three chapters exploring the various ways corporations manipulate this craving-habit loop to get us to purchase more goods; but the useful insight comes in chapter three. Duhigg points out that the literature is clear on how to change bad behaviour:

- If you want to change a bad habit, don’t rely on willpower to fight it. Instead, identify the cue and the reward, and then substitute the routine in-between for something else that results in a similar reward.

- In order for this habit modification to take, you need to believe that change is possible. And this belief thing is a catch-22: you can’t trick yourself into believing you can change; you really have to believe. Duhigg points to research showing that Alcoholics Anonymous works because its 12 Step program invokes God, and forces its members to accept the possibility of change by placing belief outside of the individual.

- Perhaps because of this ‘believe I can change’ effect, changing one keystone habit usually has downstream effects on every other habit in one’s life. Duhigg points to the body of research that shows that people who successfully create the habit of exercise often demonstrate better behaviours in all other parts of their lives — including better fiscal responsibility, better decision-making, and so on.

This is the part that is useful to you and me. Duhigg then spends the rest of the book describing habits as applied to organisational and societal behaviour — which is decidedly not as useful at the individual level.

The saving grace is that Duhigg suggests a formula for behavioural modification in the appendix of the book. He describes a four part formula:

- Identify the routine

- Experiment with rewards

- Isolate the cue

- Have a plan

The first part is the easiest: identifying the routine involves picking the bad habit that you’d like to change. Duhigg gives himself as an example: he says that he has a habit of getting up in the afternoon, walking to the cafeteria at work, and buying a chocolate chip cookie to munch on every day. This has resulted in unhappy weight gain.

The second part is more difficult. To identify why you’re doing this habit, Duhigg suggests that you should start experimenting with different rewards instead. The goal here is to figure out what reward your habit loop is after. In the case of Duhigg’s cookie example, instead of buying a cookie, Duhigg started performing other activities to see if his craving was satisfied: he took walks around the office. He started conversation with colleagues, and invited them away from their desks for a chat. He walked to the cafeteria and bought himself an apple instead.

And after each experiment, Duhigg would self-evaluate to see if the craving had been satisfied by the activity he performed.

Why is this important? Well, the nature of the reward determines the nature of the alternative routine that Duhigg would use to substitute his bad habit with. If, for example, the nature of the reward was the enjoyment of the cookie itself, Duhigg might replace the habit with something equally sweet, but healthier — an apple, for instance. But if the reward was merely an excuse to stretch his legs, Duhigg would have to replace the habit with a walk around the building, or some similarly satiating behaviour.

The step after identifying the reward is harder still: you now need to identify the cue. Duhigg notes that the literature suggests that there are only five possible categories for habitual triggers:

- Location

- Time

- Emotional state

- Other people

- Immediately preceding action

In light of this, Duhigg suggests that you write five things down the moment the urge hits:

- Where are you?

- What time is it?

- What’s your emotional state?

- Who else is around?

- What acton preceded the urge?

After a few days of recording his potential triggers, Duhigg realised that the cue for his cookie-walk habit was time; the urge to get up and grab a cookie usually hit him between 3pm to 4pm.

The last step for behavioural change — after identifying the bad habit, isolating the reward, and identifying the trigger — is to make a plan. Duhigg wrote the following on a Post-It note at his desk: “At 3:30pm, every day, I will walk to a friend’s desk and talk for 10 minutes”, and swore to perform this action at the same time every day.

He then suggests that you jot down a check for each day that you successfully perform this habit. The reward is seeing the series of checkmarks on your notepad, and keeping this habit consistent over time.

And, just like that, Duhigg successfully overcame his cookie habit.

Fin

The ideas that I’ve summarised above are literally all that is useful from The Power of Habit. There are quite a number of interesting stories, and I found Duhigg’s reporting on how consumer goods companies design their products with the habit loop in mind to be quite enlightening.

But I wish Duhigg had spent more time exploring the literature around behavioural change, and examining the various ways we may put these ideas into practice. Alas, this book was quite clearly written for different reasons; see, for instance, the chapter on Target’s ability to detect if its customers had become pregnant before they did — Duhigg published this as an essay in the New York Times Magazine and caused quite a stir when it came out in 2012.

It’s quite clear his career as corporate speaker has taken off in the years since.

I’ll reiterate my advice from earlier: if you’ve read this far in my post, go apply these new ideas to your own life by signing up for BJ Fogg’s Tiny Habits course. It’s free, it’s immensely practical, it’s short, and it’s already started delivering results for me.

I’ll write a review of the course tomorrow. Do yourself a favour and sign up today.

Originally published , last updated .