I wrote last year that I was experimenting with a technique called ‘Perceptual Exposure Playlists (PEP)’ — which builds on an effect called perceptual exposure, or the idea that repeated exposure to a large set of superficially similar samples would teach one’s brain to identify domain-specific ‘deep’ features that are necessary for expertise. So: if you want to get better at writing narrative, read lots of good narrative non-fiction; if you want to get good at designing software, read lots of well-designed code.

I mentioned in my practice post that I was going to give everyone an update in March 2019 … so here we are.

Two things have changed since I started putting PEPs to practice.

The first thing is that I’ve discovered a framework that explains why perceptual exposure works. Long-term readers of this blog would recognise this as recognition-primed decision making (or RPD — Wikipedia link here), which was significant to me because it unified all the half-formed notions I had about tacit mental models of expertise.

The second thing that’s changed is that I’ve started systematically hunting down stories of deliberate practice in the literature … and have begun to discover richer, more useful training techniques there than in the perceptual exposure literature. I’m still not entirely sure why this is, but perhaps it pays to go where all the attention is.

We’ll examine these two ideas in order.

Recognition-Primed Decision Making — Better Training than Perceptual Exposure?

I covered recognition-primed decision making in Part 4 of my framework for putting mental models to practice. As I wrote then:

Because expert intuition is often portrayed as ‘magical’, we ignore it and turn to more rational, deliberative modes of decision making. We do not believe that intuition can be trained, or replicated. We think that rational choice analysis is the answer to everything, and that amassing a large collection of mental models in service of the search-inference framework is the ‘best’ way to make decisions.

It is telling, however, that the US military uses RPD models for training and analysis of battlefield decision-making situations. The field of NDM arose out of psychologist Gary Klein’s work, done in the 90s, for the US Army Research Institute for the Behavioural and Social Sciences. In the 70s and the 80s, the US Government had spent millions on decision science research — that is, on conventional models rooted in rational choice analysis — and used these findings to develop expensive decision aids for battle commanders.

The problem they discovered was that nobody actually used these aids in the real world. The army had spent ten years worth of time and money on research that didn’t work at all. It needed a new approach.

(…) RPD is valuable to me for one other reason: that is, after a years-long search with the goal of self-improvement, I have finally found a usable model that captures the essence of expertise.

In contrast to much of the decision-making literature, recognition-primed decision-making emerged from the study of experts: firefighters, paramedics, fire squad commanders, programmers, navy officers and chess players. Kahneman and Tversky studied noobs making decisions on toy problems in labs; Klein and co studied experts making decisions in real world environments.

As part of their research, Klein and colleagues developed a technique called the ‘critical decision method’ that was designed to draw out tacit mental models of expertise. It was with this method that they were able to generalise the decision-making models that experts actually used in their fields.

In one early, successful case, Klein’s colleagues Beth Crandall and K. Getchell-Reiter applied the critical decision method to extract tacit models for detecting sepsis in premature babies. To quote from The Power of Intuition:

(Darlene, a senior nurse, checks in on Melissa, a premature baby):

… when Darlene walked past Melissa’s isolette near the end of the shift, something caught her eye. Something about the baby “just looked funny,” as she later put it. Nothing major, nothing obvious, but to her the baby “didn’t look good.” Darlene had a closer look, now noticing specific details. She noticed the heel stick had not stopped bleeding. To Darlene, Melissa seemed a little “off colour” and “mottled,” and her belly seemed a little rounded. She noticed this even though every baby had a different complexion and body shape and Darlene was not particularly familiar with Melissa’s normal state. A quick physical exam confirmed that Melissa still had an unusual amount of residual food in her stomach, causing bloating. Darlene checked Melissa’s chart and noticed that the baby’s temperature had dropped consistently over the shift. She called Linda over and asked her if the baby had seemed lethargic during the shift. When Linda replied, “Yes,” Darlene immediately raced to the phone and woke the duty physician.

“We’ve got a baby in big trouble,” she said. She explained the symptoms. The physician agreed with Darlene’s assessment of a baby in crisis and immediately ordered antibiotics and a blood culture. Twenty-four hours later, the blood culture confirmed sepsis. If they had delayed giving the antibiotic until they had the results of the blood culture it would probably have been too late.

This story has a happy ending. Thanks to an experienced nurse’s intuitive sense of a baby who “didn’t look good,” Melissa would live.

Initially, Darlene couldn’t explain what she noticed about Melissa that so alarmed her. Yes, Melissa had displayed certain symptoms that were consistent with sepsis, but each individual symptom could be explained away — as was done by a less experienced nurse earlier that day. Darlene was incredulous that the younger nurse, Linda, had written off the symptoms; however, upon further prodding she allowed that it would have been difficult to recognise the signs of sepsis “until you see them”.

Darlene’s story isn’t fundamentally different from the notion of ‘perceptual exposure’. In my original post I described how the predominant method for training chicken sexers was to hand the trainees a series of chicks and have an expert immediately give them feedback on their guesses. Over a period of months, the trainees improve in identifying the sex of the birds handed to them … even though they ‘cannot tell how they know’.

Darlene’s story shows us that similar expertise exists amongst neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) nurses. More importantly, this story demonstrates that perceptual exposure doesn’t have to be the only method for training such expertise. Using the critical decision method, Crandall and Getchell-Reiter were able to illicit the perceptual cues that Darlene and other experienced NICU nurses used to identified sepsis — even though they were initially unable to articulate the signals that they noticed. Half of the cues they identified in this manner were new to the medical literature, and — surprisingly — some cues were the opposite of sepsis cues in adults.

Crandall was then able to turn these findings into a successful training program to teach nurses the skills that Darlene (and other experienced nurses) learnt through repeated exposure. My immediate thought upon reading this was: “I wonder if the poultry companies have hired Klein to help them with their training programs!” followed by “I guess perceptual exposure training techniques aren’t that useful after all.”

Klein points out that it is a common misconception that perceptual cues may only be learnt through experience. This struck me as rather astute — given that I believed this up to a couple of months ago. And Klein puts his money where his mouth is: his entire career has been built around identifying tacit mental models of expertise in service of designing ever more effective training programs, executed in the context of organisations that wished to capture the tacit mental models of their best performers. In a segment about paramedics in Sources of Power, Klein writes:

Perceptual cues can be defined. This expertise does not have to remain in the realm of the specialist or in the intuition of the nurse or paramedic who has seen similar cases. It should be possible to train ordinary citizens to look at each other and recognise when a friend or coworker is starting to show the signs of impending heart problems.

Klein’s methods are compelling because they’ve been used to develop training programs in a variety of organisations over the course of three decades. It seems to me that RPD-driven training programs are designed to achieve the kinds of expertise that perceptual exposure purports to teach. But Klein’s methods are far better developed.

Deliberate Practice > Perceptual Exposure

In my original Perceptual Exposure Playlist essay, I wrote about how I was attempting to use PEPs to practice narrative usage in my writing:

Have you ever noticed that reading a richly imagined narrative is easier than reading a well-written expository paragraph? Have you also noticed that good non-fiction writers — in books that line the bestseller aisles, or in long essays in places like The Atlantic or The New Yorker — use a mix of narrative and exposition to introduce new ideas to readers?

The two observations are no accident. Humans find it easier to read stories than to read arguments. Mixing the two is a higher-level writing technique, one that I’ve been trying out in my recent Commonplace essays.

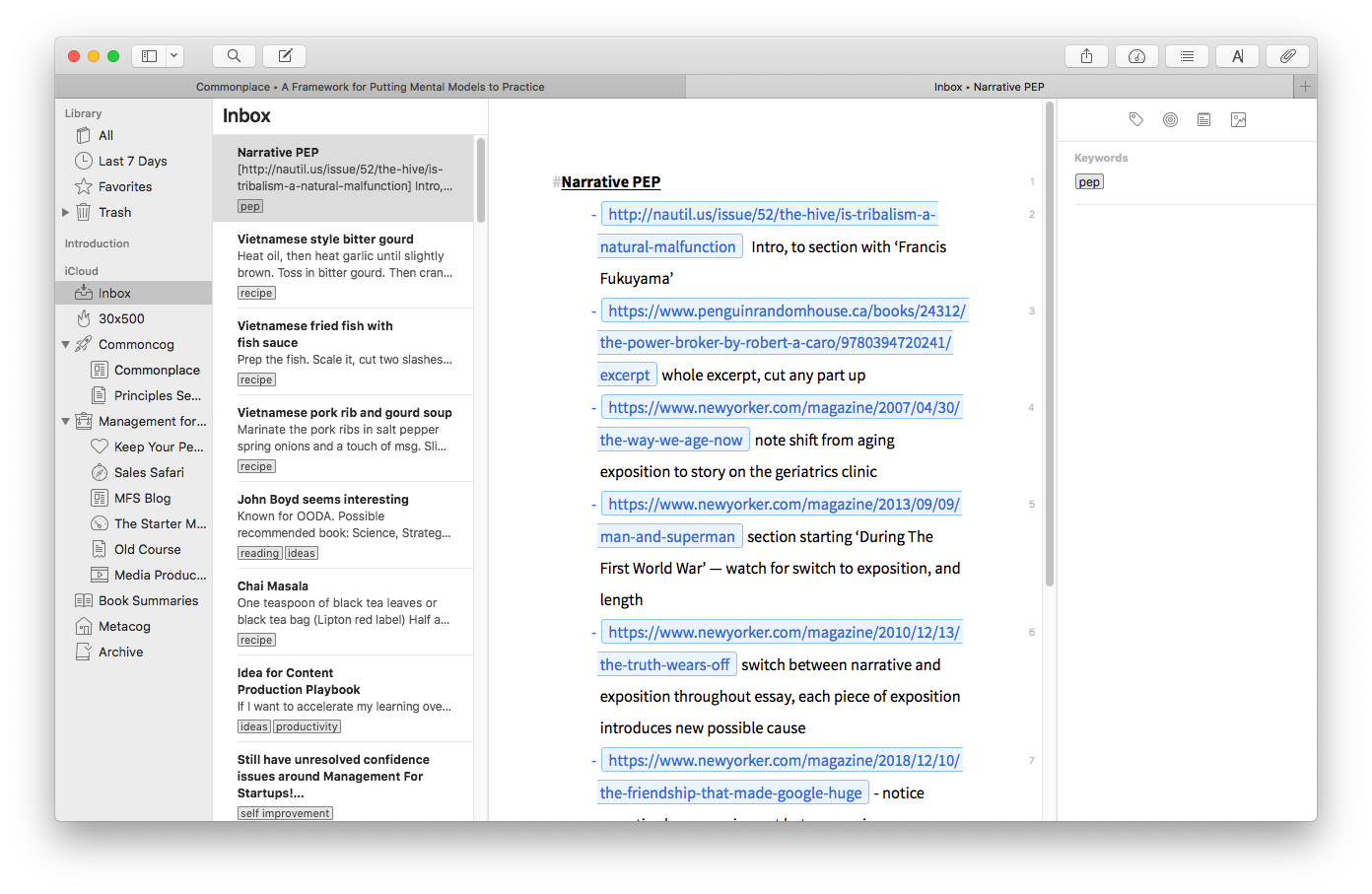

After diving into the perceptual exposure literature, I decided to create a PEP — or a Perceptual Exposure Playlist for this very task. Here’s a screenshot of the PEP in question in my writing app of choice, Ulysses:

Note that I’ve listed URLs to links I find particularly impressive. Note also that I’ve left notes on the sections that most interest me. I don’t want to read the entire piece — that would take too long — instead, I’ve opted to pick certain segments that I thought best exemplified the various ways one may deploy this technique.

As a feedback mechanism, I intend to look back at my writing at certain scheduled checkpoints — I have one scheduled for March next year, for example. But as it is, I already find myself noticing certain narrative techniques as I work my way through my daily reading list.

In the months since, I’ve noticed one major problem with this method: whenever I notice a particularly good use of narrative, I would find it difficult to use (much less remember!) that segue in my writing without first attempting it explicitly. It does seem like perceptual exposure isn’t as effective as, well, actual practice.

I could be missing the point here, though. A large part of writing ability is subconscious — when I write, I am able to transform thoughts into words without much awareness of how this process happens. It may well be that I’ve absorbed the essence of such narrative techniques without explicitly recognising that they are now part of my repertoire. What if I’ve improved as a result of my perceptual exposure but am not aware of it? Isn’t that the main claim of perceptual exposure practice, after all?

The answer is that I don’t know, and I may never know: like many skills, writing ability is a matter of intuitive perception, or ‘taste’. I write a paragraph and read it out loud to myself, and if it feels good I leave it in. I do the same when I’m editing. I don’t mean to say that this ability can’t be made explicit — it’s clear from Klein’s work that it’s possible to extract these tacit mental models from my head — but I don’t think it’s that easy to pinpoint the origins of these models, the same way that Darlene probably couldn’t explain how she learnt to notice sepsis cues in the first place.

So we’ve got a measurement problem with perceptual exposure practice, one that I'm not sure can be avoided.

I bring this up because deliberate practice is way more visceral — you know you’re getting better, because DP is so painful to do. After awhile, the pain can become enjoyable the same way that exercise is enjoyable, because you know you are getting better at whatever skill you’re trying to improve.

In my summary of Peak I wrote that Benjamin Franklin improved in his writing through DP techniques:

Benjamin Franklin got good at writing by picking articles from The Spectator, summarising them, and then attempting to recreate the original piece from the written summary. The comparison between the two pieces would serve as feedback; the fact that Franklin could easily correct the deficiencies in his writing as compared to The Spectator's version meant that he did not need a teacher. Ericsson points out that Franklin later became one of the most successful writers in America (in addition to, urm, a few other things).

This practice strikes me as more useful than attempting to read reams of narrative in the hopes of having something stick.

A concrete example suffices: I recently finished this profile of blues legend Buddy Guy, written by New Yorker editor David Remnick. In the middle of the article, Remnick cuts to a vignette from his own life: when Remnick was in college, his father, a dentist, called him and insisted that he went to a club in the Village called the Cookery to listen to a blues singer named Alberta Hunter. So important was this to Remnick’s dad that he sent him a check for 20 dollars to pay the cover charge. Decades later, at his father’s funeral, Remnick set up a boom box and played his dad’s favourite music; people left the synagogue to the strains of Alberta Hunter’s ‘Downhearted Blues’.

The entire vignette is three paragraphs. It is spliced between an exposition of Buddy Guy’s early career and Guy’s recent visit to Lettsworth, his hometown. I came to the piece expecting an account of Guy’s life; this sudden intrusion of personal history came like a stroke of colour in the middle of a black-and-white rerun. It is very effective. Remnick tells us of his father, establishes his connection to Guy, and shows us his reverence for the blues — and does all this in about 400 words. I raised my eyebrows and immediately filed it away as “notice, copy later”.

And I think the copying here is key. If I had read this without attempting it myself, it is questionable if I would ever use it in my writing. But by making an explicit effort to reproduce Remnick’s flourish, I could better understand his intent and the contexts in which I might do something similar. The same principles of deliberate practice that helped Benjamin Franklin become a better writer would apply just as well to my own attempts at narrative.

Fin

In the end, where does this leave us?

I’m downgrading my recommendation of perceptual exposure as a form of standalone practice. I think that for any serious effort at mastery, perceptual exposure can only play a secondary role in skills development. Better to focus on deliberate practice, along with other forms of explicit practice.

That being said, I think perceptual exposure does have a place in one’s pursuit of mastery: you may use it as a method to notice what is good in your field. Writing teachers have said since time immemorial that the way to get good at writing is to “read and write a lot”; perceptual exposure is probably the 'read' part. Buddy Guy himself says: “Nobody ever sat me down and said here’s B-flat and here’s F-sharp (…) Most of the people above me—John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins—I faced them, I watched their hands to see where they were going. They played by ear. And that’s how I play now. I play by ear. I don’t play by the rules.”

I've noticed that I’ve become more aware of narrative usage in the non-fiction pieces that I read — in the past, I would simply finish an article and move on; after starting PEP practice in December last year, I found myself taking small pauses to think about the usage of narrative in the piece I’d just finished before turning the page. (The Remnick piece is probably an example of this).

Perhaps perceptual exposure is simply an attempt to make explicit what humans do naturally in the pursuit of mastery. We observe something good, we copy it, and then we make it our own. The PEP technique merely asks: think about what you’re noticing while you’re noticing — your brain is a powerful machine and it’ll benefit from all the exposure.

Sounds like a good deal to me.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→