Note: This is part 2 in a series about tacit knowledge. Read Part 1 here.

Let’s say that you believe tacit knowledge exists. Let’s also say that you agree that tacit knowledge is mostly learnt through emulation, apprenticeship and osmosis.

The question that follows naturally is this: are there ways to get better at it? Is there research that tells us how to get better at emulation, or to be more effective at apprenticeship? I mentioned in my previous piece that the field of Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) is the most promising subfield of expertise research I’ve found; I also mentioned that learning ideas and methods from NDM has made the biggest difference in my own pursuit of mastery.

This post will explore what those methods are.

Two Caveats

Before I begin, two quick caveats.

First, I must admit that my usage of the term ‘tacit knowledge’ isn’t ideal. ‘Tacit knowledge’ comes from the field of epistemology, which is the philosophical study of truth. By defining ‘tacit knowledge’ as ‘knowledge that cannot be captured through words alone’, I’ve left myself open to all sorts of confusion and pedantry.

I was aware of this when I chose the term for this series.

Let’s take a quick tour of all the ways ‘tacit knowledge’ is confusing, just so you know that I am skipping over large parts of the philosophical literature:

- Tacit knowledge may be ‘embodied’ — that is, activities like riding a bike or swinging a tennis racquet have to do with the body, but not necessarily the conscious mind. Some philosophers believe that such skills are a type of tacit knowledge that is different from the tacit knowledge in more cerebral fields like programming and designing and writing. (I do not believe this is true, but the philosophical argument for why they believe this is the case will take around 50 pages of writing, so we’re not going to go there).

- Many types of tacit knowledge may be made explicit: for instance, bike riding or ball kicking may be turned into a collection of physics equations in a research paper. This is a form of explicit knowledge, and it may help you build a bike-riding or ball-kicking robot. But from a pedagogical perspective, this form of explicit knowledge is useless: it won’t help you learn to ride a bike or kick a ball. So is this really tacit knowledge? Or is it explicit? Or is it a bit of both?

- What about the kinds of tacit knowledge that can be communicated via video, or through pictures? I may not be able to explain to you how to do a complicated series of yoga poses through words alone, but if I record a quick video, or draw a series of diagrams, you might be able to learn to do so. Is such knowledge tacit, or explicit?

- And how about organisational tacit knowledge? In 1988, Taiichi Ohno published The Toyota Production System, which laid out the ideas behind lean manufacturing for the first time. He did so after resisting codification of those principles for many, many years; Ohno feared that the publication of TPS would destroy Toyota’s competitive advantage. But it turned out that the publication of Ohno’s book by itself did not lead to widespread adoption amongst Toyota’s competitors. More bizarrely, competitors who poached TPS experts away from Toyota were not able to replicate Toyota’s system in their company. It appeared that TPS required an organisational culture to develop alongside the implementation of the system itself. This phenomenon sparked off an entire subfield of research into organisational tacit knowledge.

I’ll skip ahead here and tell you that none of these questions are particularly interesting to me — at least, not in the context of this blog. This blog is a practitioner’s blog: it is interested in what is useful, not what is ‘true’. The answers to these questions will matter to you if you are a philosopher, or if you are a pedantic commenter in some online forum and you are familiar with Wittgenstein, Dreyfus, or Polanyi. But if you are a practitioner and you observe someone in your company demonstrating high levels of expertise, you probably aren’t interested in the answers to any of these things. You just want to learn how to acquire what is in your more skilled colleague’s head.

So here’s my way of side-stepping everything above: when I say tacit knowledge in this series, what I am really interested in is ‘expert intuition’ or ‘expert judgment’. This is the “expertise, full of caveats” that I talked about in Part 1. Expert intuition is tacit because it is incredibly difficult to investigate, incredibly difficult to make explicit, and incredibly difficult to teach.

In principle, it is possible to make many forms of expert intuition explicit: if you can find just the right sort of skilled practitioner, or if you have access to someone who is trained in the NDM tradition, he or she may be able to extract and explain the tacit mental models of expertise that is responsible for the practitioner's performance. But this leaves us with two problems:

- First, you may not find such a person in your domain. NDM research is considered niche, even in the field of judgment and decision making; people with both high levels of expertise and the ability to synthesise that expertise into discrete principles are also exceedingly rare.

- Second, such an explanation might not be helpful to you if you want to gain their skills. (Think of the physics equations around bike riding — none of that is going to help you learn to ride a bike!) Similarly, an expert programmer might explain her judgment — full of caveats and gotchas! — but this might not be very useful to you.

I’ve mentioned both of these problems in passing in my previous piece. The crux of it, I think, is that regardless of whether or not tacit knowledge in your domain may be made explicit, it is more useful for you to act as if it is were not possible. This stance frees you to hunt for learning methods that do not involve explanations alone.

My second caveat is the following: even if tacit knowledge is incredibly confusing, it is still useful to introduce it. I’ve learnt that people aren’t typically interested in the ideas from NDM when I explain it to them. But if I first explain the concept of tacit knowledge — the idea that some forms of knowledge, embedded in human expertise, cannot be captured through words alone — they immediately map this phenomenon to their own experiences, and then they become more receptive to my gushing about NDM training methods.

So, with these two caveats in mind: let us begin.

How The Naturalistic Decision Makers Do It

In order to get better at learning through emulation, we need to understand the nature of the tacit knowledge that we are after. The dangerous thing about calling this sort of tacit knowledge ‘expert intuition’ is that it is very easy to hear ‘intuition’ and go “oh, so there’s nothing we can do to learn it, move along now.”

But this is not true. The entire field of NDM research is built around taking expert intuition, extracting it and turning that into training programs for organisations (in most cases, the military). In many of these projects, the organisations measure training outcomes, find improvements, pay the researchers, and then have the researchers move on to the next project.

How do they do this?

As far as I can tell, NDM researchers have three tools in their toolbox. First, they conduct something called ‘Cognitive Task Analysis’ (CTA), which is a set of interviewing techniques designed to explicate tacit mental models of expertise. This is not an easy task. An earlier version of this was called the ‘Critical Decision Method’, which focused on ‘tough cases’ of expertise-driven performance, in order to elicit whatever it is that was going on in the practitioners’s heads. Today, the set of techniques is much larger, and they are all lumped together under the umbrella of CTA.

If you study the development of psych approaches, CTA is simply an extension of older techniques used by the behaviourists to analyse psychological effects under experimental conditions. (Paul Harmon, for instance, talks about this evolution here). NDM researchers typically perform cognitive task analysis at the outset of their projects — this is how they extract tacit knowledge from the experts they study.

Second, many NDM researchers rely on a model of expert intuition called the recognition-primed decision making model (RPD). This model, developed by Gary Klein and his collaborators in the 90s, lies at the heart of their understanding of expert intuition. RPD explains how expert intuition works, and it tells us why experts have so much difficulty when it comes to explaining their expertise. NDM practitioners use the RPD model as a guide during their interviewing process, and they also use it as a guide to the development of their training programs.

Third, and last, NDM researchers develop training programs designed to let less experienced practitioners acquire expert judgment of their own. NDM practitioners typically have some familiarity with pedagogical techniques, but in this, they, too, are guided by the RPD model.

It’s a common misconception to look at this and think: “oh, when you can make tacit knowledge explicit, then you can just explain things to people and they will get it.” This is not the right conclusion to have. As we shall soon see, large portions of expertise is tacit, and for certain types of expertise, the training methods must also be tacit in nature — that is, built around copying, and emulation, and scenario training, not explicit instruction. What NDM gives us is a rigorous method to reason about such things.

Because RPD is so central to the work of NDM researchers, we should probably start with the model and explore everything that it implies if we want to use it ourselves.

The Recognition-Primed Decision Making Model

Imagine that you were in my shoes, and you were seated next to a senior programmer who skimmed your code and gave you several recommendations after a couple of seconds. “How did you do that?” you ask, and he replies: “Oh, it just felt right.”

In order to get at his expertise we must ask: what went on in his head during those few seconds? The RPD model gives us a clue.

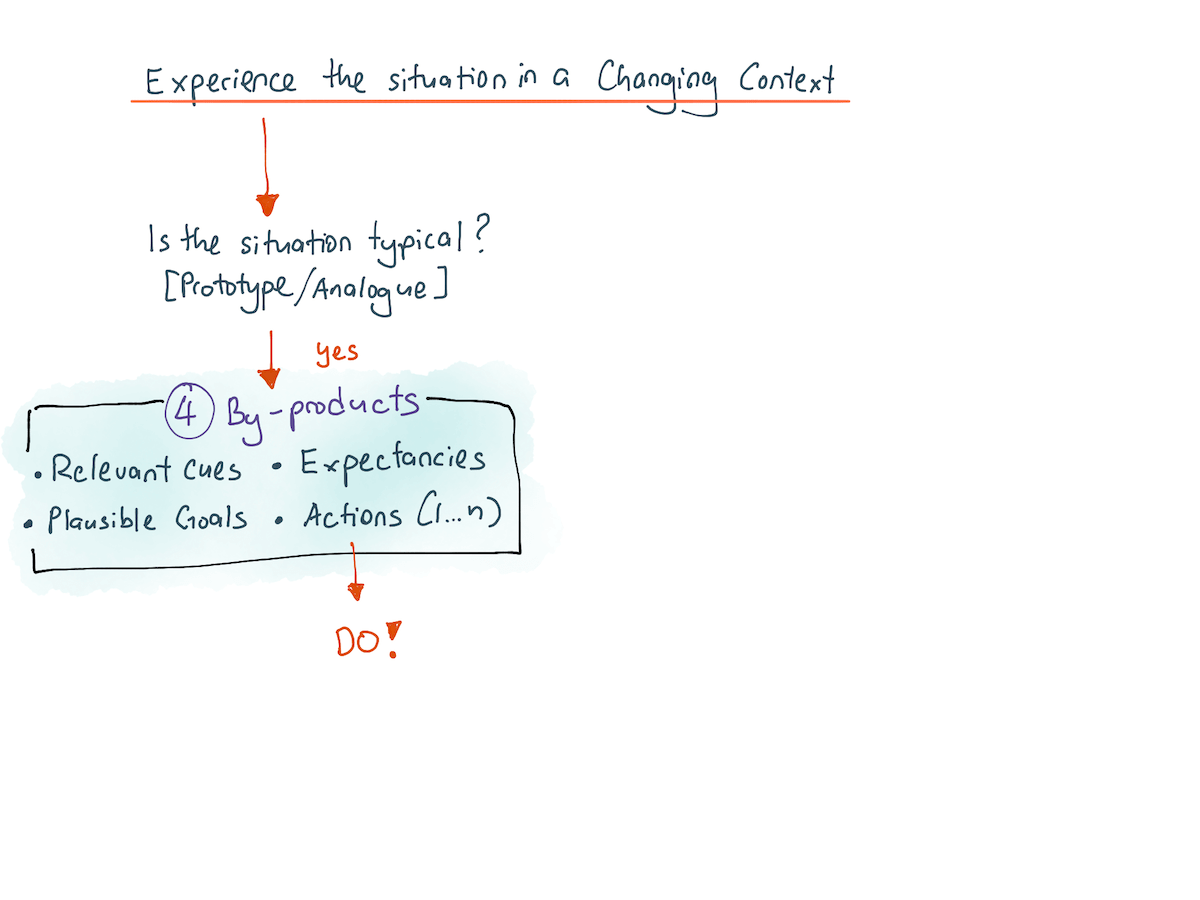

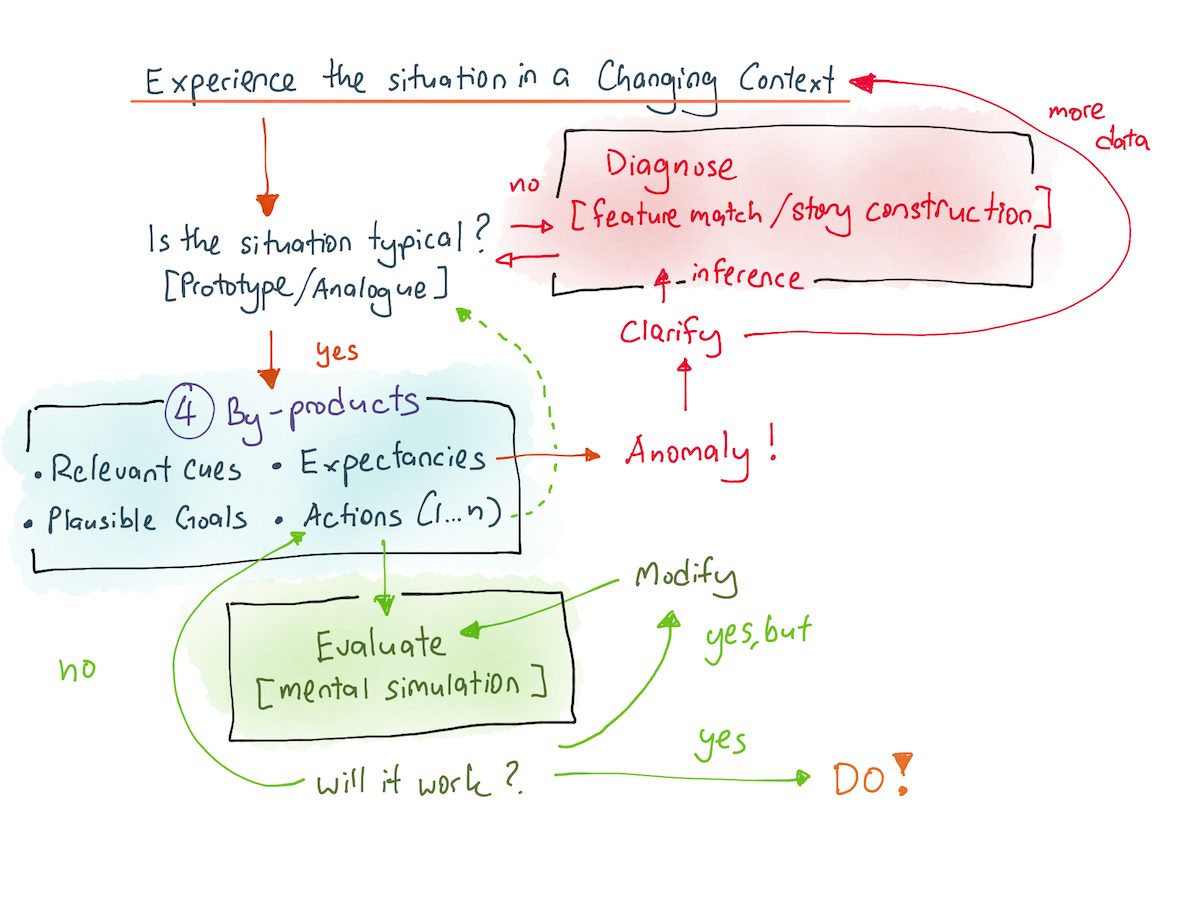

The recognition-primed decision making model describes what humans do when they are problem solving in the real world. It tells us that when an expert encounters a problem in the wild, their brain observes the situation in a changing environment and immediately pattern matches it against a collection of prototypes. If they recognise what they see as an example of a prototype — even if the situation they see is non-routine! — their brain immediately generates four things:

- A set of ‘expectancies’— When diagnosing a situation, experts will construct mental simulations of how the events have been evolving and will continue to evolve. In other words, they will have some expectations for what happens next. The more experienced they are, the more clear-cut these expectancies become. For example, an experienced firefighter might take in a scene and know instantly where the fire might travel, or how a bad situation might develop. A programmer reading a codebase might find several weird kludges, and immediately suspect a submodule to be a persistent source of bugs.

- A set of plausible goals — The expert would know what to prioritise in the moment, and what to defer to a latter time. When under fire, for instance, a Marine Corps squad leader would have to prioritise between keeping his people alive, getting to better cover, and achieving mission objectives. His recognised prototype tells him where his priorities lie in a given situation, freeing cognitive resources to conduct other forms of thinking. Similarly, a programmer may receive a set of business requirements, and immediately generate a prioritised list of goals in their head according to the recognised prototype.

- A set of relevant cues — Experts know what to pay attention to; novices do not. Recognised prototypes come with a set of cues — for instance, when you’ve just started driving, you may find yourself overwhelmed with the dials and knobs and mirrors you have to keep track of. After a few months, however, you do these things automatically, and shift your attention to specific affordances in your car depending on the situation. (For instance, when turning a corner, you know to check your side mirrors and you know what to watch out for.)

- An action script — Last, but not least, if the situation is typical, the expert would have a course of action immediately generated in their heads. If the situation is not typical, the expert’s brain would still generate a set of actions, but the expert would slow down to walk through each action step in their head.

The recognition of goals, cues, expectancies and actions is part of what it means to recognise a situation. What is important to understand is that all of this recognition happens within implicit memory. This is why experts are not able to verbalise what they are doing.

Implicit memory operations are subconscious. Our ability to recognise faces, for instance, is an implicit memory operation, and we cannot say how it happens. When your friend Mary walks into the room, you immediately recognise her face. But notice that remembering her name is a different process entirely: this is because facial recognition is recognition; name retrieval is recall, and the two operations use different subsystems in your brain. (Gillund & Shiffrin, 1984)

When an expert says “it just felt right”, what they mean to say is that they recognised the problem as an example of a prototype in their heads, which generated the four by-products; this implicit memory operation happens so quickly that they cannot verbalise how they came up with it. They can only say “it just felt right!”, the same way you might say of an acquaintance: “I know her, I just can’t remember her name!”

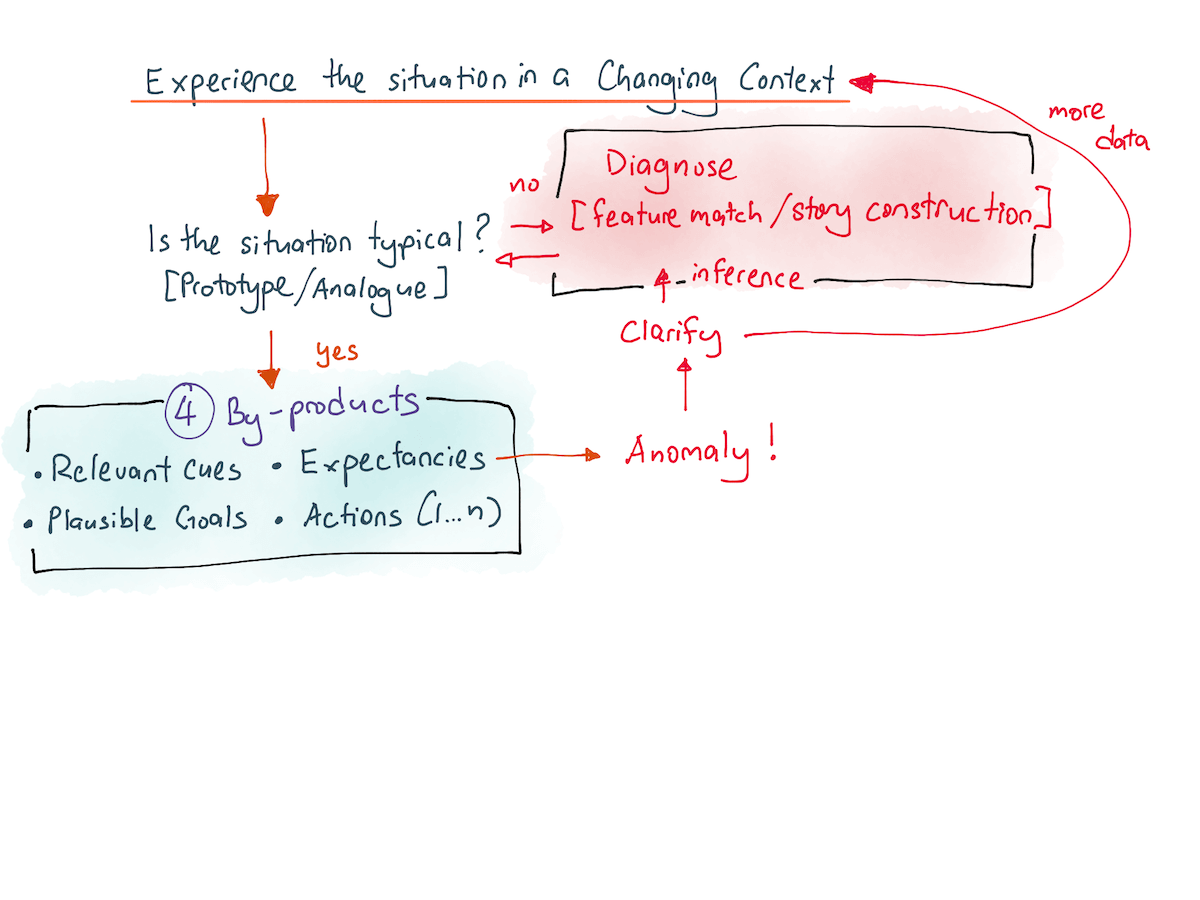

The RPD model that we have explored so far is not complete. Experts sometimes come across situations that do not match what they have in their heads. Or, they uncover evidence that violates their original expectancies. In such an event, the expert immediately recognises that their matched prototype is mistaken, and so they drop back down to pattern recognition. They try to construct a narrative or a simulation to explain what they are seeing in front of them, in order to match with a different prototype. This is where a firefighter or programmer or Marine Corps squad leader might choose to gather more information — the firefighter might take a step back to look for other signs of smoke; the programmer might choose to dig deeper at a particular subsystem; the squad leader might decide to scout by a different path.

Our RPD model now looks like this. Everything in red is the second variation of the RPD model, which includes repeated cycles of pattern matching:

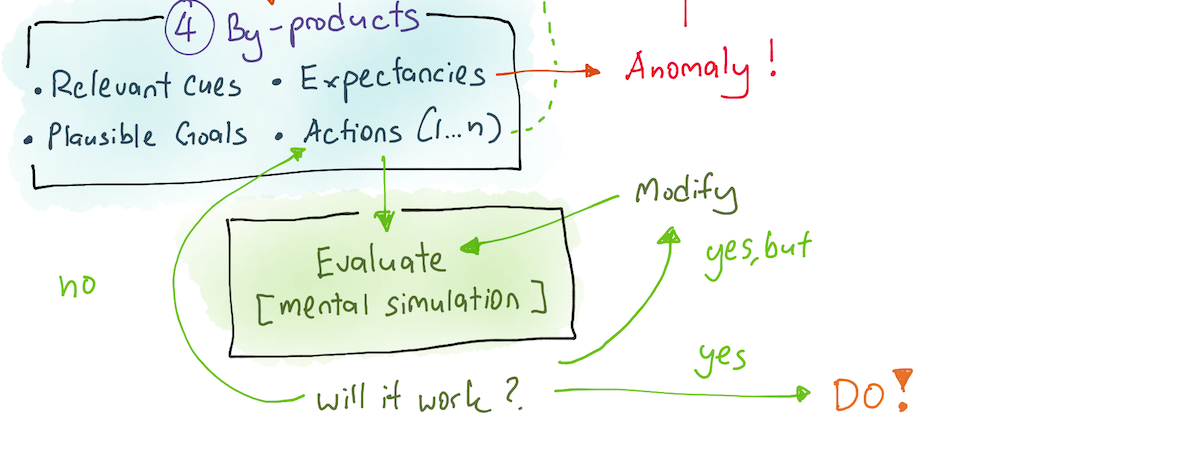

The third, and last variation of the RPD model concerns itself with actions. In normative decision-making theory, humans pick multiple choices, evaluate their pros and cons against each other, and then pick the best possible option, perhaps by using some expected value calculation. In the real world, however, Klein and his fellow researchers discovered that experts do not default to this strategy. Instead, they ‘satisfice’ — they pick the first available option that fits their criteria.

To be more concrete, what happens is that the expert will pick a course of action, simulate it step-by-step in her head, and then either choose it, or discard it due to inadequacy. They will repeatedly go through each imagined course of action until they find the first one that meets all their criteria. If they run out of actions to perform, they will fall back to prototype recognition. But if they find an action that seems to work in their mental simulations, they will immediately carry it out.

Klein explains (Sources of Power, Chapter 7) that a strategy like ‘cycle through each course of action one at a time, until a good one is found’ is more common when:

- Time pressure is greater.

- People are experienced in the domain. This makes them more confident in their judgments, and therefore allows their brains to default to this problem solving strategy.

- The conditions are more dynamic (meaning the context shifts rapidly, rendering decision analysis costly, because everything has to be thrown out).

- When the goals are ill-defined.

In contrast, people are more likely to use comparative evaluation when:

- They have to justify their choices — perhaps to a boss.

- When conflict resolution is at play (you have to satisfy multiple stakeholders with different requirements).

- When people have less experience, and therefore less confidence in the options that their brains generate.

- When they have to optimise — that is, when they are required to find the best course of action.

- And, finally, when the situation is computationally complex — for instance, when analysing an investment portfolio to select the best strategy. Tasks like these involve so many considerations that they tend to overwhelm the pattern-recognition machinery in our heads.

In most cases, however, the default human response is to satisfice: that is, to generate and then cycle through actions one at a time until the first suitable one is found. This is both good or bad, depending on the situation: in fact, much of the cognitive biases and heuristics tradition argue that this method of thinking is what leads to erroneous human judgment. Klein simply points out that this is how our brains work.

This final discussion concludes our examination of the recognition-primed decision making model. The complete model now looks like this:

RPD is useful because it gives us a model with which to understand human expertise. When you apprentice under someone, what’s actually happening is that you are building up prototypes in your implicit memory — that is, you are identifying cues, learning plausible goals, internalising action scripts, and storing expectancies. At the same time, you are also collecting the experiences necessary to simulate action scripts in your head.

Klein mentions that RPD is similar to other models of expertise, such as Lee Beach and Terry Mitchell on image theory, the skills-rules-knowledge scheme by Jens Rasmussen, and other models of expertise by P. A. Anderson, Wohl, and Dreyfus and Dreyfus. According to Klein (Sources of Power, Chapter 7), RPD’s contribution is merely that:

- It appears to describe the decision strategy used most frequently by people with experience.

- It explains how people can use experience to make difficult decisions.

- It demonstrates that people can make effective decisions without using a rational choice strategy. (emphasis mine)

Which begs the question: how do we use this?

How Do We Use RPD?

One of the most obvious things that falls out of the RPD model is that we can now use it to carry out cognitive task analysis. In other words, we actually have a shot at understanding what went through my senior programmer’s head.

When interviewing an expert, NDM practitioners will always zero in on ‘tough cases’ that the expert has experienced, in order to examine the recognition-driven process in their heads. Specifically, CTA interviewers will establish a timeline of events of the case, and then ask questions to elicit:

- What cues did they notice first?

- In that particular situation, what did they expect to happen next? (expectancies)

- What priorities (goals) did they have?

- What courses of actions immediately came to mind?

These four by-products is how you get at the tacit knowledge of practitioners.

Later, when they are designing training programs, NDM researchers would be able to rely on these explicated prototypes and the four by-products to come up with effective training scenarios. The goal, of course, is to expand the set of experiential prototypes in their learners’s heads.

The RPD model should immediately suggest certain training methods to you. Let’s go through some of these levers, which I think should be obvious if you pause to think about them:

1) Systematically Expand the Set of Prototypes You Have

The first method of application follows easily from the model: because so much of expertise is pattern matching, many of the training programs that are designed by NDM practitioners are oriented around expanding the set of prototypes in their learners’s heads.

In 1993, NDM pioneer Beth Crandall studied a group of expert neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) nurses who could ‘just tell’ if a premature baby was suffering from sepsis — way before other nurses or doctors could. The nurses insisted that they were able to tell from ‘intuition’ and ‘experience’, and that was all there was to it.

Crandall conducted a series of CTA interviews with them and successfully extracted the perceptual cues they noticed. She was then told to turn this into a presentation to be used for onboarding all the NICU nurses at the hospital group she was working with. Several perceptual cues these nurses were using to identify sepsis were unknown to the medical literature at the time; the nurses themselves did not know what they were looking for, since they were responding to a ‘gestalt’ — an overall picture that the baby presented.

But Crandall made an important modification to her presentation. She did not present the cues in isolation, like a lecturer would in a more typical talk. Instead, she presented the cues through a series of stories, because stories more accurately captured the sorts of experiences nurses would have in the field. (e.g. “You first notice baby George breathing shallowly. He looks normal, but his blood pressure is slightly elevated. You check his chart …”)

What Crandall was trying to do with these stories was to expand the set of prototypes in her audiences’s minds. The perceptual cues she had made explicit was only the tip of the iceberg — the key was to embed them within plausible scenarios that the nurses might encounter. Later, less experienced nurses could apprentice under more experienced ones, and they would share a vocabulary of perceptual cues that was made explicit by Crandall’s work.

How do you use this insight if you are a solo practitioner? One way could be to systematically seek out situations where you have less experience, in order to expand the set of prototypes in your head. Another way might be to select and use exercises that help build out the prototypes you have; for example, if you are a programmer, code katas might be useful — but only to the degree that they reflect the problems you might encounter in your domain.

In practice, attempting to use CTA to extract and then create training programs is difficult. CTA is itself a skill, and most NDM practitioners say that you need months if not years of experience to become proficient at it. That said, I’ve experimented a little with this, and I think there are a few other ways you can put it to use:

2) Identify When A Practitioner Has a Prototype That You Do Not

Another, less obvious way to use RPD is to identify when a practitioner is using her intuition. When you notice a practitioner making a rapid assessment of a problem, when they say “it just felt right”, or when they give you an explanation that is full of caveats and gotchas, you now know that they are using an implicit-memory recognition operation that stems from their experiences. If you face a similar situation and you find yourself doing option comparison, this should tell you that your colleague has a prototype that you do not, and that this might be something you want to acquire.

In other words, you can use this to build a skill tree for yourself.

RPD is useful because you should also know to ask about the cues, expectancies, priorities, and courses of actions that present themselves in the practitioner’s mind. Don’t get me wrong: this will not be a good extraction of their tacit knowledge, because expert intuition is difficult to explicate, and CTA is itself difficult. But it’s surprisingly useful to just ask questions along these lines — at the very least, the hints that you’ll get out of it will be marginally better than naive copying, or asking “how did you do that?!”with no conception of the four by-products.

3) Get Better At Mental Simulations

A second lever that falls out of the RPD model is the idea of giving learners sufficient experiences in order to simulate effectively.

Recall that mental simulation is a key part of RPD: it drives the identification of expectancies, and it allows practitioners to simulate possible courses of action before picking one to execute. More experiences mean more accurate mental simulations.

As a result of Klein’s research, Marine Corp squad leaders are now trained to identify decision requirements for their own performance. Klein writes:

The decision requirements exercise is for the squad leaders to identify the key judgments and decisions facing them, why they are difficult, and where they can go wrong. These decision requirements are the high drivers, the specific decision skills that they need to polish. In addition, by identifying the decision requirements of their mission (e.g., identifying a good landing zone for helicopters, judging the amount of time it will take a squad to move from one position to another), the squad leaders could find ways to practice these judgments, such as getting feedback from helicopter pilots about the adequacy of a landing zone, or timing different squads as they moved across terrain, to become more sensitive to factors such as the nature of the terrain, the effect of weather, and the amount of equipment carried. Thus, the decision requirements let the squad leaders identify their own needs, for their own missions, and let them discover ways to engage in practice and obtain feedback for their judgments and decisions.

You can imagine how this might be useful: when under fire, a marine squad leader might need to evaluate different move options; having a training regiment that emphasises experiencing and measuring movement times across different terrain types would be incredibly useful for mental simulations performed in the field.

4) Get Feedback From An Expert on Both Recognition and Simulation

Sometimes, it’s just plain difficult to create appropriate training programs for yourself. One way around this is to reflect on your past experiences, and then go to more skilful practitioners to get feedback on the actions that you chose in past events.

When doing so, it’s important to copy the method that’s used in CTA: you should describe the event linearly, as you experienced it, never revealing more information than you had at the time. For instance, if you want to make better decisions around managing people, you might choose to describe an experience where a subordinate reacted negatively to you, and walk through that event as it unfolded. You should not tell the expert what you discovered later, after the events had already transpired. In simple terms: you should put the expert in your shoes.

When doing this, compare:

- What cues it was that you noticed vs what cues they picked up on. (Sometimes this could be expressed in the follow-up questions they ask during your story-telling.)

- What you expected to happen next vs what they expected to happen next.

- What actions you thought to do vs what actions they thought to do,

- And finally: what priorities you had in that situation, vs what priorities they might have instead.

I’ve adapted this idea from Klein’s cognitive critique — a tool he uses in his work with Marine Corps squad leaders:

Cognitive critiques help the squad leaders reflect on what went well and not so well during an exercise, and to use this reflection to increase how much they learned from experience. The critique is a simple exercise, consisting of questions about how the squad leader had estimated the situation (Was it accurate?), uncertainty (Where was it a problem, and how was it handled?), intent and rationale (What was the focus of the effort?), and contingencies (reactions to what-if probes). The checklist could be used after tactical decision games as a way for the squad leaders to compare notes, get feedback, and see how others were perceiving the situation. The checklist, primarily designed to be used after field training exercises, was a way to enrich experiences by reviewing them, much as a chess master goes over a game record.

There are many more training methods to NDM, but I’ve found that nearly all of them are built around several core ideas:

- They expand the learner’s collection of prototypes.

- They increase the experience base necessary for mental simulations.

- They involve getting timely feedback from more skilful practitioners.

NDM research is interesting to me, mostly because their publications often contain descriptions of training programs that work. I read their research mostly as a form of inspiration — you could also say that I’m using it to expand the set of possible training programs patterns that I have in my head.

How Do We Know This Model Is Accurate?

One question that you might reasonably ask is: how do we know that the RPD model is true? I’ve described NDM’s methods to you, and you might have caught on to the fact that none of what I’ve described is experimental. NDM researchers do not use hypothesis testing; there is no concept of falsifiability in their work. Klein himself readily admits that NDM is “nearer to anthropology than psychology.”

Klein gives us a defence of his field in the conclusion of Sources of Power:

The studies I have described are not classical science. We did not calibrate our instruments and present stimuli that were carefully measured to determine their exact visual angle when projected onto the retina. These are the trappings of science but not the central features.

What are the criteria for doing a scientific piece of research? Simply, that the data are collected so that others can repeat the study and that the inquiry depends on evidence and data rather than argument. For work such as ours, replication means that others could collect data the way we have and could also analyze and code the results as we have done. It will be difficult for others to conduct interviews using our methods, but we have published articles describing our methods, so others can learn them. After all, I could not replicate experiments in gene splicing without a considerable amount of training, so the fact that training is needed in data collection to study naturalistic decision making does not present a logical problem. In recent years there have been studies replicating our findings, particularly the findings about the RPD model (Mosier, 1991; Pascual & Henderson, 1997; Randel, Pugh, & Reed, 1996).

Regarding the nature of our data, one weakness of our work is that most of the studies relied on interviews rather than formal experiments to vary one thing at a time and see its effect. There are sciences that do not manipulate variables, such as geology or astronomy or anthropology. Naturalistic decision making research may be closer to anthropology than psychology. Sometimes we observe decision makers in action, but we rely on introspection in nearly all our studies. We ask people to describe what they are thinking, and we analyze their responses. We do not know if the things they are telling us are true, or maybe just some ideas they are making up. We can repeat the studies or, better yet, other investigators can repeat the studies to see if they get the same results. Nevertheless, no one can confidently believe what the decision makers say.

Here Klein weasels out of it by targeting laboratory methods: he argues that mainstream experimental psychology focuses too much on what may be easily tested in the lab. He ends his defence with:

(…) Both the laboratory methods and the field studies have to contend with shortcomings in their research programs. People who study naturalistic decision making must worry about their inability to control many of the conditions in their research. People who use well-controlled laboratory paradigms must worry about whether their findings generalize outside the laboratory.

One way to evaluate a naturalistic decision-making approach is by its products: the nature of the ideas and models that it generates and the applications it produces. If NDM and the study of different sources of power turn out to make little difference, then we will lose confidence in the approach more surely than any debate over what is science. (emphasis added)

In the two decades since Sources of Power was first published, NDM has only become more established as a field of research. More militaries around the world are using NDM methods to extract tacit models of expertise from their best operators, in order to turn that knowledge into training programs; Nasdaq uses NDM researchers to design user interfaces to augment the expertise of experienced fraud investigators on their staff. Klein himself wrote a famous paper with Daniel Kahneman on the situations where expert intuition was valid, and where it might not be valid. Most interestingly, Robert Hoffman, an NDM pioneer and one of the co-authors of the Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, has spent a good part of the last decade working on an epistemology for the entire field.

These are all signs, I think, that NDM captures something true about the world. But be that as it may, I believe that this shouldn’t be of much consideration to you, if you simply want to use this for your career.

I have argued elsewhere that if you are primarily a practitioner, your epistemology should be different than if you were a scientist. If you are a scientist, you will want to know what is true by the standards of scientific truth — this typically means successful replication over a number of years, culminating in meta-analyses of multiple randomised controlled trials with sufficient statistical power. But if you are a practitioner, what you want to do is to learn what can be useful to you today, in the pursuit of your goals. Your evaluation of an idea should be structured around whether the idea works for you — which is a different bar for truth compared to that of the scientist’s.

NDM lies at the highest level in my hierarchy of practical evidence: I have tried their methods and their ideas in my life, and nearly every one of them have led to improvements. I’ve spent this essay talking about how I’ve chased down the implications of RPD and attempted to use them in my pursuit of expertise. But it's likely that I’m only at the beginning of this chase.

There is a lot more in this domain that I haven’t yet discovered. I suspect there’s a lot more that is rewarding still. But don’t take my word for it: try the RPD model as a lens for seeing the expertise of the people around you. What do you want to get good at? Who around you is already good at it? Go find those people, ask them questions, copy them, and learn.

Read Part 3: The Three Kinds of Tacit Knowledge.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→