How to think about corruption when talking about Asian businesses. Part 4 of the Asian Conglomerate series.

Note: This is Part 4 in a series of articles and cases on Asian Conglomerates. Read Part 3 here. You may read more about the Asian Conglomerate Series here, or view all the published cases here.

John D. Rockefeller was the founder of Standard Oil, and the richest tycoon of the Gilded Age. At one point he was worth 2% of the US’s GDP; he was so rich and so powerful that it took a good 30 years before he was finally reigned in by the US government.

He was also very corrupt.

There are numerous documented instances of this corruption in Titan, Ron Chernow’s biography of Rockefeller. My favourite example is probably that of A. N. Cole, a New York State senator, who wrote to Rockefeller on New York State Senate stationery in 1878, proposing himself as an ‘attorney’ to be hired by Standard Oil to campaign against a free-pipe bill. At the time, state legislatures issued exclusive oil pipeline charters to specific companies, giving them permission to lay pipe within the state. This suited the Standard Oil monopoly just fine, as it prevented competitors from laying competing lines. Reformers in the late 1870s began introducing measures in several state legislatures to enact ‘free-pipe bills’, which would enable a free-for-all. Standard Oil was worried. It began organising lobbying campaigns, hiring lawyers to pose as incensed farmers and landowners in favour of the status quo, and recruiting senators to cripple bills with unacceptable amendments.

Cole’s letters to Rockefeller were hilariously specific in their money-laundering instructions:

Two or three good attorneys will be wanted in the Senate, and five or six in the Assembly, and these I have no hesitation to employ, if authorized to do so … Government bonds are better to deal in than money, since were “attorneys” to be paid in cash, it might be construed into corruption, but then one can sell bonds, you know, in fact dealing in them is an eminently becoming business … In Heaven’s name, don’t make this letter public, since, were you to do so, I fear my brethren of the Methodist Church might fear I had so far fallen from grace as to leave no hope of recovery.

In another example, a Standard Oil executive became a state senator, and proceeded to act like he had never left the company:

While Standard Oil gadflies pounced on the political bonds between [Standard Oil trust members] the Paynes and William Whitney, they missed a more flagrant case of political corruption: that of Johnson Newlon Camden, who served as a West Virginia senator from 1881 to 1887 but never severed his ties to Standard Oil. Approaching his 1881 election to the U.S. Senate as a straight business proposition, he favored a liberal distribution of cash to the West Virginia legislature to secure results. As he plaintively told Flagler that year, “Politics is dearer than it used to be—and my understood connection with the Standard Oil Co. don’t tend to cheapen it—as we are all supposed to have bushels.” This was prelude to an urgent request for “$10,000 in some turn—stocks or oil—Please keep an eye out and let me know.” Apparently, Standard Oil obliged, for in the next letter, Camden reported victory to Flagler. “I also appreciate sincerely the substantial kindness of the Ex[ecutive] Com[mittee] — and used it without hesitation as I needed it temporarily.”

Even after entering the Senate, Camden continued to correspond with Rockefeller and Flagler as if he was still an active Standard Oil executive, and he discussed the trust’s negotiations with the B&O Railroad on U.S. Senate stationery. He organized a railroad with Oliver Payne and urged Rockefeller, Flagler, and Harkness to join them. Throughout his term, Camden stood sentinel over Standard Oil interests, and when two pipeline bills inimical to the trust appeared in the Maryland legislature in 1882, he acted promptly, informing Flagler with satisfaction, “My dear Mr. Flagler, I have arranged to kill the two bills in Md. legislature at comparatively small expense.”

In fact, in a great twist of irony, Rockefeller attempted to buy the very senator whose legislation ultimately caused Standard Oil’s downfall:

From Standard Oil’s viewpoint, the most threatening bill was introduced in December 1889 by Ohio senator John Sherman, brother of General William Tecumseh Sherman. A few years earlier, Rockefeller tried to buy his way into the senator’s good graces. In August 1885, soliciting a campaign contribution for Sherman, Mark Hanna had told Rockefeller that “John Sherman is today our main dependence in the Senate for the protection of our business interests.” Dubious at first, Rockefeller finally sent a check for six hundred dollars (around $19,500 in 2025 dollars). Before long, the protector of business interests proved a turn-coat, flailing Standard Oil as a corporation so rich that it bought entire railroads. In debates over the senator’s antitrust bill, Standard Oil was constantly held up as a prime example of the problem to be remedied. Flushed into the open, Rockefeller took the unusual step of publicly rebuking Sherman’s legislation. “Senator Sherman’s bill is of a very radical and destructive character, proposing to fine and imprison all who directly or indirectly participate in organizations over which it is even doubtful whether Congress holds any jurisdiction.”

The opposition of the trusts only hastened passage of the law. On July 2, 1890, President Harrison signed the Sherman Antitrust Act, which outlawed trusts and combinations in restraint of trade and subjected violators to fines of up to $5,000 or a year’s imprisonment or both. President William Howard Taft later identified Standard Oil as the chief reason for the law’s passage. To its proponents, the law proved a severe disappointment, a stillborn piece of legislation. It was vague in meaning and poorly enforced and so riddled with loopholes that it was popularly derided as the Swiss Cheese Act. By outlawing cooperative efforts through trade associations, it forced many companies into mergers to curb excess capacity in their industries, spurring further concentration and subverting the act’s intention. As for the main target of the law, the Standard Oil juggernaut was not deflected by this nuisance. For many years, the Sherman Act was a dead letter, and big business happily went on as usual. (…) Never one to hold grudges in business, unfazed by the new law, Rockefeller supported the reelection of Senator Sherman in 1891.

These actions are difficult to imagine today. But if we consider Standard Oil’s actions in the context of United States commerce at the end of the 19th century, the corporate trust was simply doing business as it was understood. There were few constraints on business and politics. When Ohio representative James A. Garfield ran for president in 1880, he sounded out a Cleveland contact, one Amos Townsend, as to whether Rockefeller would be willing to contribute to his campaign. Townsend advised Garfield to go about it indirectly; Rockefeller ended up being one of the largest donors to Garfield’s bid for the presidency. At the time, distrust of powerful business was already in the air, and anti-monopoly sentiment was starting to build. Garfield would be the first of many US Presidents to grapple with the quandary of whether it made better sense to court Rockefeller’s money, or exploit public animosity against him.

It wasn’t until 1909 — 29 years after Garfield’s election — that the U.S. Justice Department sued Standard Oil. And it wasn’t until 1911 that the Supreme Court ordered that Standard Oil be broken up into 39 independent corporations. Amongst these corporations were Standard Oil of New Jersey (which became Exxon), and the Standard Oil of New York (which became Mobil). The stock of these child companies doubled in the subsequent years. Because Rockefeller controlled a quarter of the shares of those resulting companies, the breakup actually propelled his wealth to levels never before seen.

That wealth still exists today. Amongst other things, a small portion of it is invested via Venrock (‘Venture’ + ‘Rockefeller’), a venture capital firm formed in 1969 on top of already successful family investments. Venrock, in turn, invested in companies such as Intel, Apple, 3Com and DoubleClick; it was the largest outside investor in Apple at the time of its IPO.

Where did that wealth come from? Ultimately, it came from control of the right industry, in a prosperous young country, for a brief period … that, plus partial dominance of the country’s commerce, its political systems, and its resources. I remember finishing Titan and going: “oh, so Rockefeller was basically an Asian tycoon.”

Skill and Corruption

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room.

It is difficult to talk about Asian Tycoons without also talking about how corrupt they are. To state it crudely, and from the least charitable viewpoint possible: Asian conglomerates are mostly run by corrupt businessmen, exploiting weak institutions to gain access to coveted, cornered resources.

It’s no wonder that so many Western journalists, or local polemists, dismiss tycoons with “ahh, they succeeded because they are corrupt”, or “they run businesses built around political access”.

But then witness: how worshipful business writers today seem to be of Rockefeller. Notice how podcasts lionise Standard Oil or contemporaries like Cornelius Vanderbilt or Jay Gould.

To be fair, the folks who study these individuals and these businesses are not the same ones who would heap moral scorn on Gilded Age tycoons. It’s also likely that the individuals who do moralise on such topics will feel the need to criticise Rockefeller and his ilk, for the sake of consistency (or at least the avoidance of perceived hypocrisy).

But there does seem to be a double standard here. When I tell folks that I am obsessed with Asian tycoons, a good number of reactions are “Why? They’re just corrupt” — with the implication that whatever they do is not ‘really’ business skill, since they got a leg up from the governments of their day. And yet these same folk, if pushed, would admit to listening to the Acquired episodes on Standard Oil, or to have curiosity — or respect — for these old American businessmen.

If you believe that it is worthwhile to study Rockefeller, then you should also believe that there’s value in studying Lee Byung-chul. It’s inconsistent to say that one is worth studying more than the other because one has more skill whereas the other won through corruption. Whatever skill is present is present alongside the corruption, not in spite of it — both tycoons were equally corrupt.

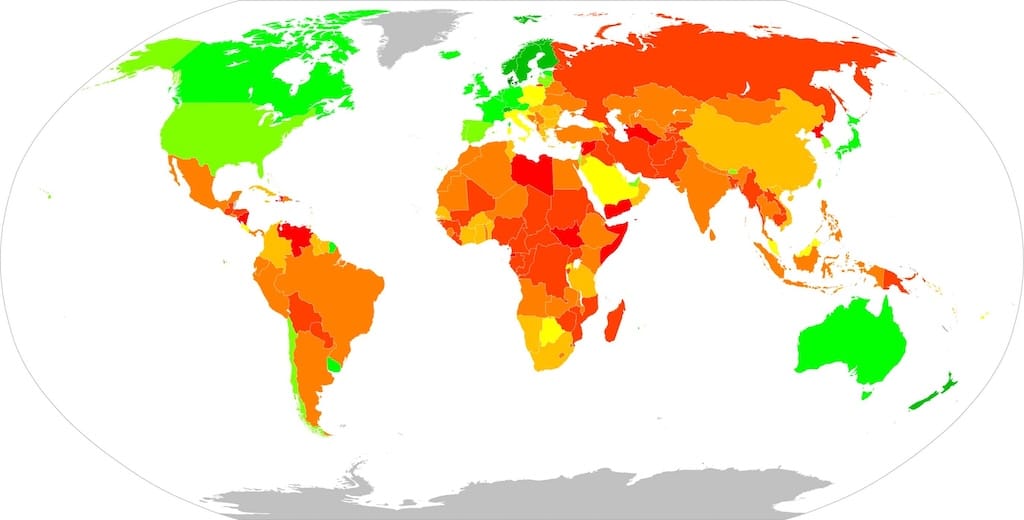

Corruption is a Natural By-Product of Weak Institutions

I try very hard not to touch on politics here at Commoncog. I like to say that Commoncog is focused on the art of business — and therefore not interested in high falutin’ political commentary. But this position has always been a bit of a lie: yes, many things in business are not politically connected, but many things are. In truth, the nature of business is always shaped by the socio-political systems of the day. We’ve spend a lot of time talking about operational excellence but less time talking about how, in certain situations, operational excellence is not the highest order bit for business success. You don’t have to be operationally excellent if you have a government-granted monopoly, for instance. And you would be in for a world of hurt if you believe that operational excellence alone will let you win against those with the ear of government. In other cases, as we’ll soon see in this series, the very nature of a market is shaped by governmental decree. This limits the type of businesses that one can start.

The Asian Conglomerate Series is the first time it has become impossible to talk about business without also talking about politics. And so I guess it’s time.

How should we think about corruption?

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Operations topic cluster, which belongs to the Business Expertise Triad. Read more from this topic here→

This article is part of the Capital topic cluster, which belongs to the Business Expertise Triad. Read more from this topic here→