This is part 8, the final part of the Principles Sequence, a series on the Ray Dalio book. Read the overall book summary here.

In 1989, Steven Covey published his most famous book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. It was a huge hit; some commentators credited it with single-handedly creating the ‘business self help’ genre.

7 Habits was a product of its time. In retrospectives, Covey said that he reacted to the trend of self-help books of his generation to focus on superficial ‘personality traits’ — surface level attributes that people could adopt easily. Instead, he wrote 7 Habits to focus on ‘character traits’, which he regarded as the result of timeless and universal principles.

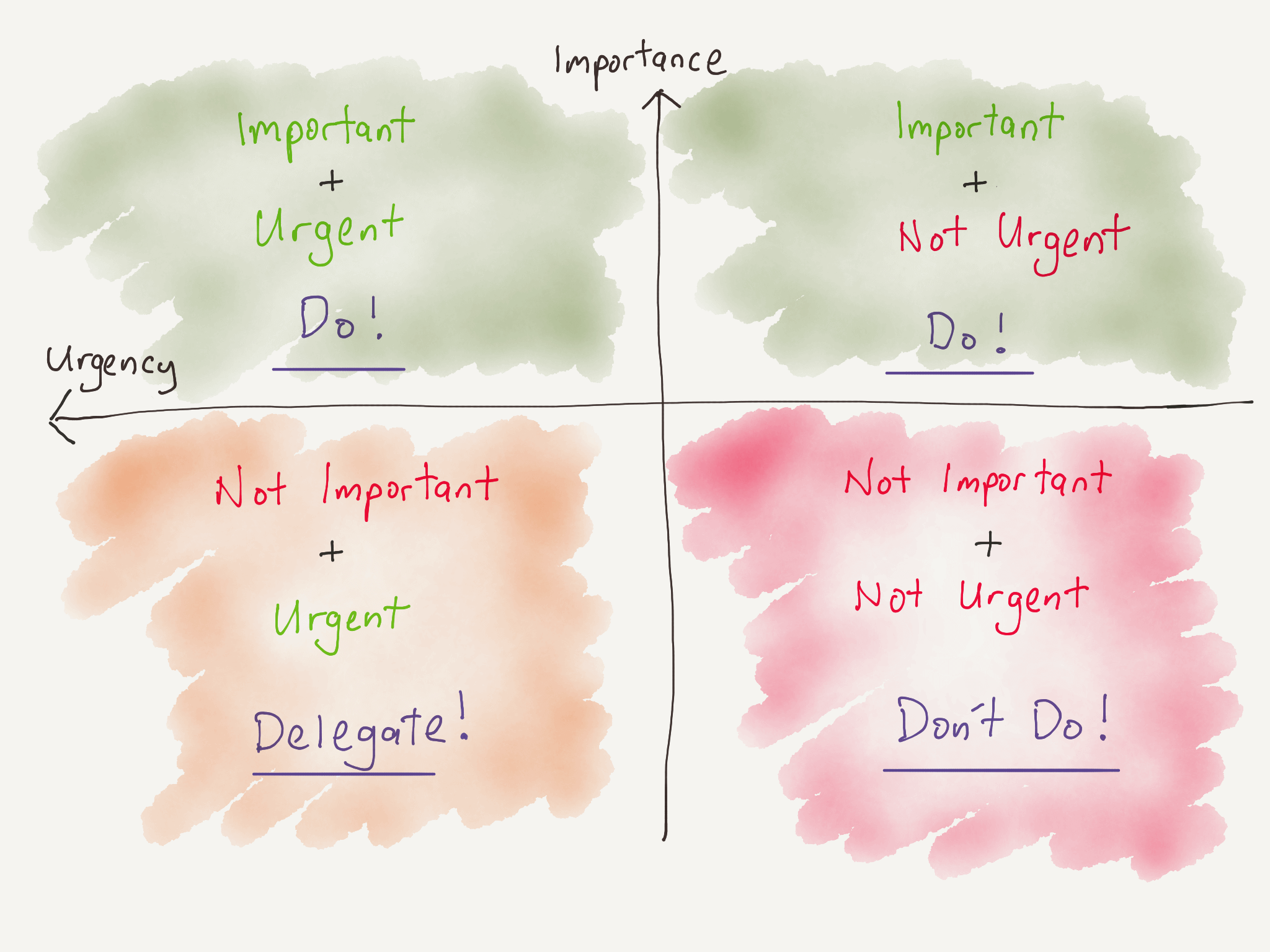

Some of Covey's ideas have spread into mainstream thinking on motivation, time management, and life skills. When I was growing up, my dad always told me to do “first things first”, which I now realise is an echo of Covey's third habit (that is, to prioritise and do what is most important first). Years later, my boss taught me to do task management according to the four quadrant model of prioritisation: draw two axes on a piece of paper, one for importance, one for urgency, and then lay tasks out in one of the four quadrants created by the two axes.

This, too, came from Covey's 7 Habits — though I had no idea at the time.

If I were to summarise Ray Dalio’s Principles in a single sentence, it is that it is an odd but valuable book that is the product of an odd but valuable organisation, made possible only by their success in a uniquely fast-paced industry.

It is also a product of our time.

When Dalio started his hedge fund, Bridgewater, in his two-bedroom Manhattan apartment in the 70s, his experiences were coloured by the age of ascendant finance. He writes, in Part One, that “everyone was talking about the stock market” while he was growing up, and described how he started buying stocks as a 12 year old. Glossed over in his biography are the events that led to his termination on Wall Street (and eventual founding of Bridgewater): he was fired from a trading house because he brought a stripper to a party and punched his boss in the face.

The truth is that Dalio cut his teeth at a time where the finance industry grew faster as a portion of the national economy than in any other period in history. Both Principles and 7 Habits are probably impossible to divorce from the personalities that wrote them. As an example of this, see Matt Levine’s tongue-in-cheek skewering of Dalio in this Bloomberg piece titled “Bridgewater’s Bosses Are Fighting Over Something”:

I joked on Twitter that I never understood how Bridgewater gets any investing done, but of course there's a computer that does the investing. ("After honing ideas through debate and discussion, Bridgewater employees write trading algorithms that buy and sell investments automatically, with some oversight.") One stylized model for thinking about Bridgewater is that it is run by the computer with absolute logic and efficiency; in this model, the computer's main problem is keeping the 1,500 human employees busy so that they don't interfere with its perfect rationality.

I've mentioned elsewhere that Principles is a rationalist approach to effectiveness in life. It is, in many ways, after the same thing as Covey's 7 Habits — except it was written by a rigorous systematiser, and implemented in the context of a successful hedge fund.

Let’s talk about that for a moment. I’ve implied, over the course of this series, that I think Principles can be understood by the fact that Bridgewater is a hedge fund and that Dalio has been successful at accurately modelling macroeconomic behaviour.

No other industry has as tight a feedback loop from action to results as the finance industry does. If Bridgewater made bad decisions, the market would punish them — and in so doing, damage their reputations in a very public manner. The nature of Bridgewater’s business thus made it both necessary and possible to codify the decision-making Dalio and his associates did during their work. It seems Dalio’s pursued this to an extent no other hedge fund has, but I attribute this to his personality; Dalio was writing down every trade he did and his reasoning for each all the way back to when Bridgewater was one guy in a two-bedroom apartment.

Dalio’s hard-won success at predicting macroeconomic trends also explains his confidence in treating ‘reality as a machine’. He writes, early in the book, that he got very far treating commodity markets as ‘machines’ — predicting, for instance, that since cattle, chickens and hogs consumed corn and soymeal, and that corn and soymeal competed for acreage, and because livestock ate predictable amounts of feed, and gained weight at predictable rates, it was possible to project when the meat would come to market and how much corn and soymeal would be consumed in the process.

He’s also faced great failures in his pursuit of understanding market realities. In 1982, Dalio nearly bankrupted Bridgewater after declaring that the US was headed for a depression. It wasn’t. Dalio was publicly shamed, and lost everything; at one point, he writes, he had to borrow $4000 from his dad to make ends meet. To hear him tell it, everything he’s done since has been to ensure he never made the same mistakes again.

If you’ve been through a failure as total as Dalio has, and come out of it alive, and rebuilt your fund from the ground up to become one of the most successful in the world, and then successfully predict the 2008 financial crisis, you’d be pretty darned confident that you could understand reality, model it, and develop a plan to deal with it.

You and I probably think that reality is too complicated and too unknowable to understand, but if there’s one thing you should take away from this post, it is that Dalio believes — he really believes — with rigour, discipline, persistence, and effort, it is possible to master reality: to first understand it, and then to bend it to your will.

Reaching The End

We’ve reached the end of the Principles Sequence with this post. It’s been quite a journey, returning to a book that is in many ways just as difficult for me to read today as it was when I was a student during a dark period at university.

I opened this post with Steven Covey because he created the genre of business self-help books, a genre that Principles is going to be categorised under, for better or worse. Covey was a business coach, not a trader. He wrote 7 Habits after spending a good deal of time reading a large oeuvre of success writing, from which he distilled down to ‘7 habits’ in order to teach to his clients. (Whether or not Covey is ‘believable’ is an exercise left for the alert reader).

There are a number of commonalities between 7 Habits and Principles. For instance, the entirety of Covey’s first habit — “Be Proactive” — is captured in Dalio’s exhortation to “Own Your Outcomes”. And this is no surprise; taking responsibility for everything that happens to you is probably one of the oldest pieces of life advice. I gather that so many people repeat it because it’s true.

In sum, Dalio’s Life Principles consist of the following five ideas:

1 — Embrace reality and deal with it

Don’t lie to yourself. Don’t fall into the trap of wishing reality worked differently, or that your own reality is different. Instead, embrace reality and learn to deal with what you’ve been given. Reality is a machine you can understand and eventually manipulate. If things don’t turn out the way you expect them to, then the problem is in your understanding of reality, not in reality itself. Pain is therefore a signal to update your understanding of reality.

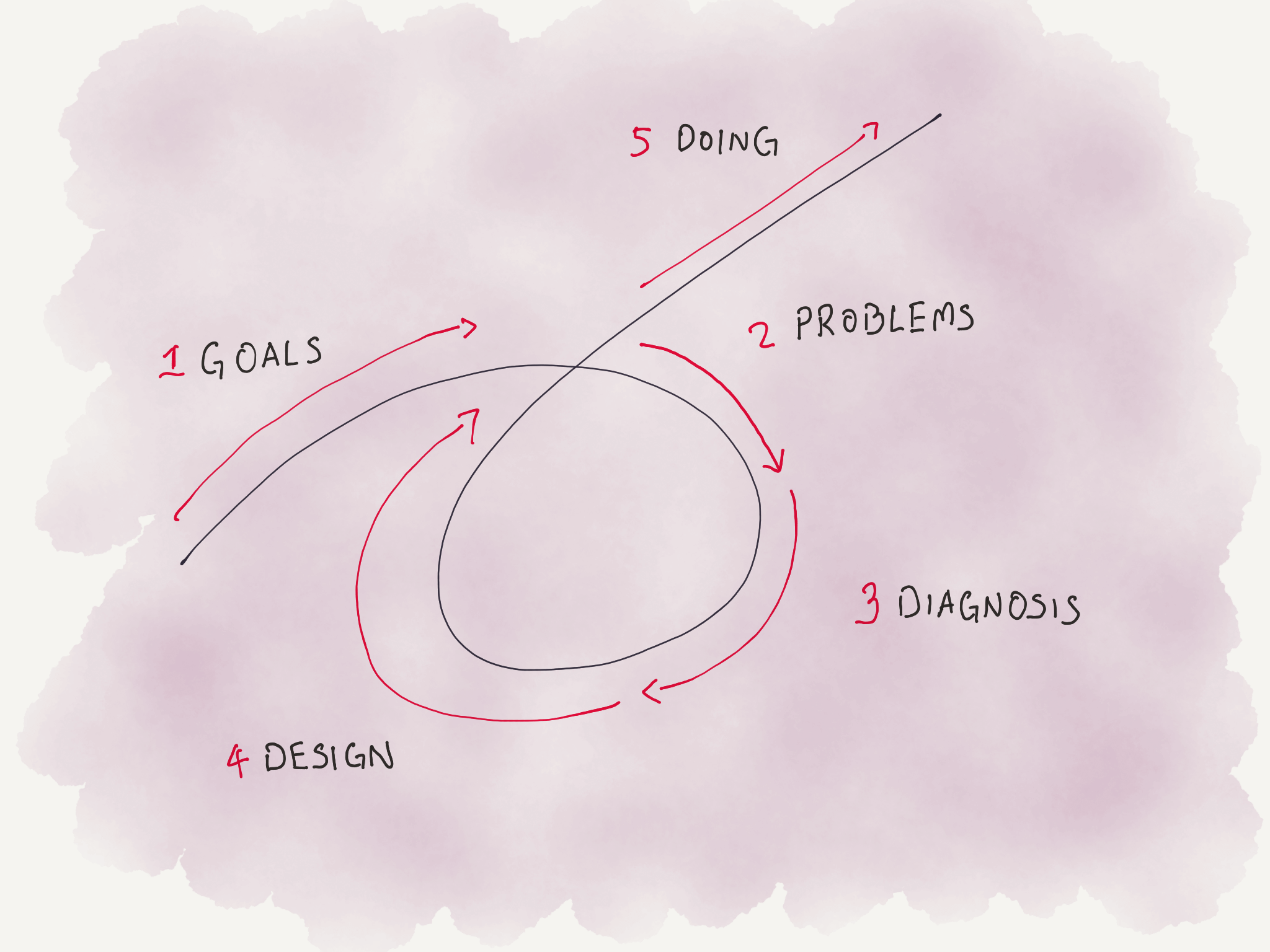

2 — Use the 5-step process to get what you want out of life

Have clear goals. Identify and don’t tolerate the problems that stand in the way of your goals. Accurately diagnose those problems to get at the root cause. Design plans that get you around them. Execute those plans.

Remember that nobody is good at all five steps. You have two choices: get better at the steps you’re bad at, or get people who are better at them to help you.

3 — Beware your ego barrier and your blind spot barrier

Both barriers are why most people fail to achieve their goals.

Your ego barrier is why you lie to yourself. You don’t want to be wrong. Your job is to gently fight your ego to accept reality as it is.

Your blind spots are the things you can’t see due to your unique perspective of life — from which springs your strengths.

To overcome both barriers, engage in thoughtful disagreement with believable people, and update your beliefs by triangulating with multiple such people. A person is believable when they have achieved at least three successes, and they have credible explanations for their approach. Ignore advice from people who are less believable than you because this is inefficient. Engage in debate only with people who are of equal believability. Ask questions and listen when discussing with people who are more believable than you.

4 — Understand that people are wired very differently

An understanding of personality archetypes, along with knowledge of how to deal with them and work with them, will help you to reach your goals. This is because no man is an island — any goal worth achieving demands meaningful relationships while performing meaningful work. Therefore, any tool that enables you to orchestrate people better will result in an edge.

5 — Learn how to make decisions effectively.

Decision making is an art that consists of learning and then deciding. It pays to get better at it. This involves learning to ‘synthesise reality’ and ‘navigating levels’ while you are learning the information necessary to make your decision. When it is time to decide, you will need courage to do what is necessary. This courage comes from not lying to yourself.

Use reason, logic, and common sense to make your decisions, instead of intuition. Know when to gather more information vs making a decision. Use expected value calculations when deciding on something. Be imprecise — 80% of the value comes from 20% of the information. Remember that you only ever need to consider five to ten important factors when making a decision.

Fin

Covey’s book has helped thousands of people since it was first published in 1989. I hope Principles does too, though it’s not nearly as simple as 7 Habits, and it’s not genre-defining by any means. As with all such books, it’s easy to read Principles and not do anything about it. Putting it into practice is where things get difficult.

I like Principles because it’s changed my life. Maybe it works for me because I was ready for it, or maybe it’s worked because rational approaches to life are particularly attractive for people with my personality type. I know some friends who can’t get past some of the more bizarre prescriptions that Dalio makes; that could well be you.

Regardless of your reaction to the ideas in this sequence, I hope I’ve done a good enough job to convince you that there could be something here. There’s some truth to the proverb that you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink; some ideas have to be packaged in particular ways in order to be effective for particular personalities. But if you consider yourself rational, or you find the idea of being rational to be attractive, then Principles is probably for you.

Originally published , last updated .