Deliberate practice is the notion that a specific type of practice leads to superior performance outcomes in any area where expertise is possible. You might have heard of it if you’ve been following this blog; I covered deliberate practice when summarising Cal Newport’s 2016 book Deep Work, and again when discussing Gary Klein’s approaches for decision training in Part 5 of my framework for putting mental models to practice.

What I’m willing to bet, however, is that you’ve heard of deliberate practice in the context of Malcolm Gladwell’s ‘10,000 hour rule’ — the mistaken notion that 10,000 hours of practice would turn anyone, at any age, for any skill, into a master practitioner.

Gladwell introduced this idea in his 2008 book Outliers, and based it on the research done by psychologist Anders Ericsson and co, who were the first to describe ‘deliberate practice’ as we know it today. The memetic power of this so-called ‘rule’ is such that Ericsson had to spend an entire section in his book (the popular science tome Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise published in 2016 by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt) debunking Gladwell’s rule. But I don't think I'm mistaken to assert that ‘10,000 hours’ has entered the popular lexicon; I myself find it hugely enjoyable to say “just put in your 10k hours” when talking to friends about practice.

Deliberate practice is interesting to me for two reasons. The first is that building career moats in my life necessarily requires me to go after rare and valuable skills. Therefore, anything that helps in the pursuit of such skills is likely to be interesting and relevant. Second, the deliberate practice research makes an awfully attractive claim: that anyone, given enough determination, can become good at any skill. They merely have to do lots and lots of difficult deliberate practice.

In fact, the research tradition around the deliberate practice model of expertise makes exactly these two claims.

First, it claims that talent is overrated. Ericsson et al truly believe that expert performance in the vast majority of fields may be explained by differences in the quantity and quality of deliberate practice — in fact, that the effect sizes from deliberate practice far dominate when compared against innate talent, genetics, or other factors. It was this claim that originally attracted attention to Ericsson’s research, when he (along with colleagues Ralf Krampe and Clemens Tesch-Romer) published their groundbreaking paper The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance in 1993.

Second, the deliberate practice tradition claims that there is a right way and wrong way to practice in the pursuit of mastery. The most striking result from this second claim is the idea that ‘practicing’ via rote repetition — e.g. playing a familiar piece from start to finish, starting a new, bog-standard programming project, completing a typical college essay — does not result in improvements of the sort that is necessary to achieve mastery in a problem domain.

It’s important to separate these two claims, because the first claim is under heavy attack. (So heavy, in fact, that I don’t expect it to survive the next decade.) The second claim, however, is one that is most relevant to us as practitioners. We’ll deal with them in turn.

Claim One: Talent is Overrated … Not

There are a number of problems with Ericsson’s first claim that deliberate practice is all that matters, and I think Harry Fletcher-Wood has a good summary of problems with deliberate practice here. I’ll run through them quickly.

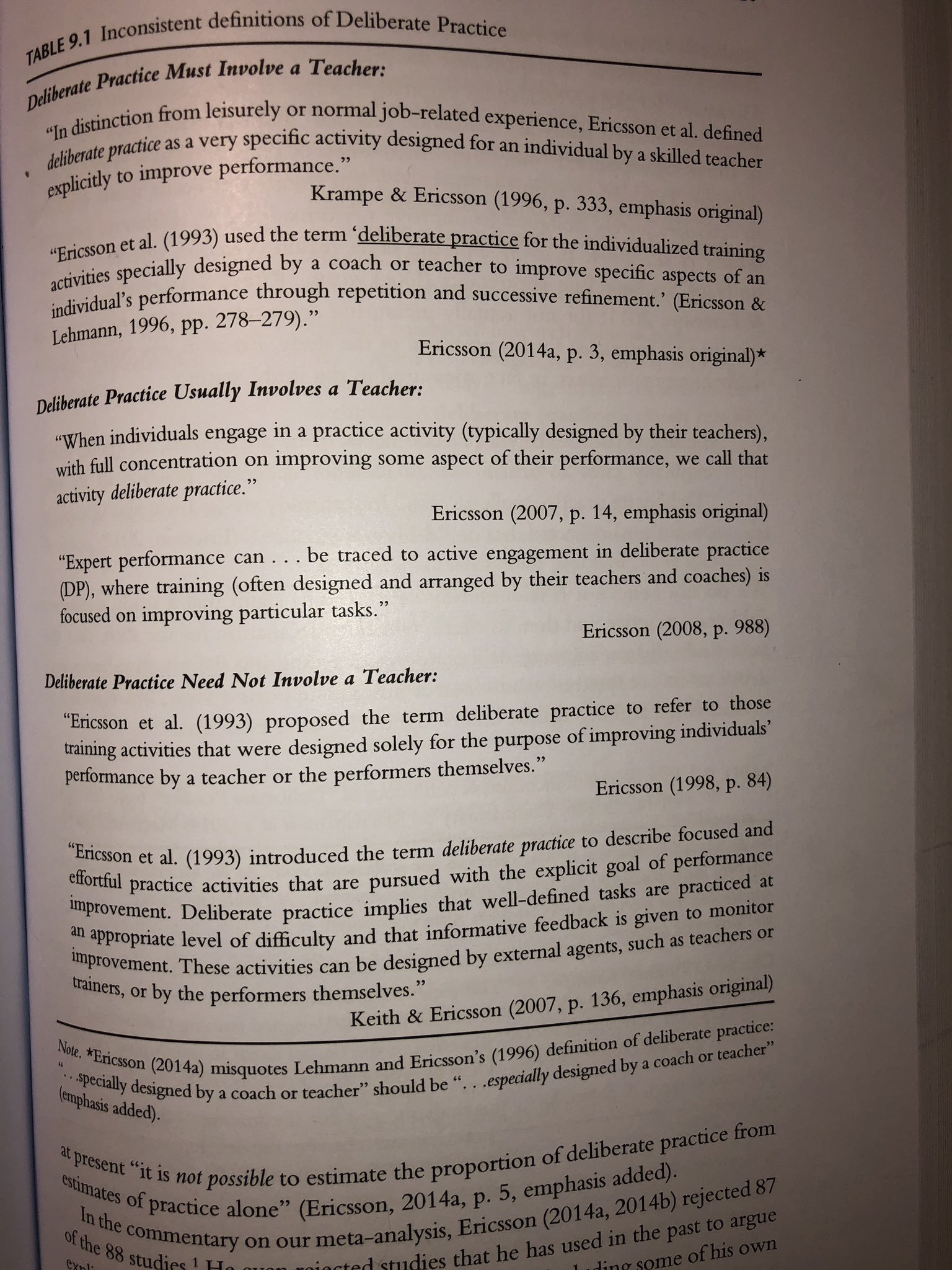

First, Ericsson has been quite inconsistent with definitions of deliberate practice over the years. See this screenshot of Hambrick et al’s The Science of Expertise (taken from Twitter):

Hambrick’s compilation of the various descriptions goes a long way in explaining my own confusion on the topic — I’ve read multiple conflicting explanations of deliberate practice over the years, and never felt like I was fully certain of Ericsson’s definition. Of course, it could well be that Ericsson was developing his theory as he progressed — in Peak, for instance, he argued that the principles of deliberate practice was what was universally applicable — teacher or no.

Second, I’ve found Ericsson’s claims on the universality of deliberate practice to be a little expansive. In the introduction of Peak he writes:

While the principles of deliberate practice were discovered by studying expert performers, the principles themselves can be used by anyone who wants to improve at anything, even if just a little bit. (emphasis added)

but also implies (later in the book) that he doesn’t think it works for certain domains:

Some activities, such as playing music in pop music groups, solving crossword puzzles, and folk dancing, have no standard training approaches. Whatever methods there are seem slapdash and produce unpredictable results. Other activities, like classical music performance, mathematics, and ballet, are blessed with highly developed, broadly accepted training methods. If one follows these methods carefully and diligently, one will almost surely become an expert. I’ve spent my career studying this second sort of field.

If we were to be strict about this, I’d say that he shouldn’t make the claim so carelessly in the introduction. Ericsson doesn’t make such expansive claims in his academic work; I’d wager that he’s done so because Peak is a popular science book and this is common in the genre. I also think his academic book The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance is a more rigorous treatment of the topic; I intend to read that as I continue in my journey to put deliberate practice to, err, practice.

On that last quote, I should note that autodidact Max Deutsch took Ericsson up on his challenge and decided to create an accelerated learning program for the NYTimes crossword puzzle here; it seems to have worked. So perhaps Ericsson meant to say that training programs could be developed for any skill; it’s just really difficult if you are the first one to do so.

Third, Ericsson continually claims that practice is all that matters and talent is overrated. This is an incredibly suspicious claim, for two reasons. First, it seems improbable that in the narrow area of expert performance we find that practice dominates, whereas in everything else, we find that genetic factors have an equally large (if not greater) effect on outcomes. (This latter bit — that genes matter in determining IQ, mental health, personality traits, aptitude, and others — is so well replicated so as to not be in serious dispute any longer.) Second, Ericsson’s claim is extraordinary, and therefore should be backed by extraordinary evidence — and yet that doesn’t seem to be the case. See, for instance, this meta-analysis, which shows smaller than expected effects, and which appears to stand despite replies here and here. The New Yorker also has a story on a variety of criticisms on Ericsson’s work, though I can’t say if it is a fair representation of all involved.

For what it’s worth, I find the assertion that Ericsson’s critics level against him a lot more believable: at the highest levels of performance, genetics and innate factors matter because everyone is practicing the same amount; in other fields and at lower levels of performance a combination of genetics, opportunities, and environment affect individual performance just as much as the number of hours spent in effective practice. To quote Hambrick et al:

… the data indicate that there is an enormous amount of variability in deliberate practice—even in elite performers. One player in Gobet and Campitelli's (2007) chess sample took 26 years of serious involvement in chess to reach a master level, while another player took less than 2 years to reach this level.

Some normally functioning people may never acquire expert performance in certain domains, regardless of the amount of deliberate practice they accumulate. In Gobet and Campitelli's (2007) chess sample, four participants estimated more than 10,000 h of deliberate practice, and yet remained intermediate level players. This conclusion runs counter to the egalitarian view that anyone can achieve most anything he or she wishes, with enough hard work. The silver lining, we believe, is that when people are given an accurate assessment of their abilities and of the likelihood of achieving certain goals given those abilities, they may gravitate towards domains in which they have a realistic chance of becoming an expert through deliberate practice.

Fourth, to my knowledge, there hasn’t been many attempts to falsify the hypothesis. Perhaps there are people out there who have been subjected to deliberate practice and have put in the requisite number of years but have not been shown to demonstrate good expertise. Do these people exist? If so, what are the conditions for failure? What are the limits? Traditionally, Ericsson would assert that “this person has not received proper deliberate practice”, but that’s a circular claim. If the athlete is successful, deliberate practice worked. If she hasn’t, perhaps she did not do deliberate practice properly. The paper You can’t teach speed: sprinters falsify the deliberate practice model of expertise appears to be an interesting note from two researchers who did attempt to try.

Claim Two: Deliberate Practice Trumps Normal Practice

I’ve summarised the academic criticisms of claim one, but that’s of little interest to us as practitioners. Scientists are, after all, interested in what is true. As practitioners we should be more interested in what is useful.

Is deliberate practice good enough to work? My opinion — one that’s informed by painful experience attempting to implement the results of Ericsson’s research — is that, yes, deliberate practice does work, but it’s really difficult to turn the principles into a practice program if you are in a field where no ‘highly-developed, broadly accepted training methods’ exist.

Ericsson would say that my very statement above — the one where I framed the issue as working in a field with no ‘highly-developed, broadly accepted set of training methods’ necessarily precludes the possibility of deliberate practice. To explain this would require us to take a short detour.

First, before we may understand deliberate practice, it pays to pause and consider what Ericsson calls ‘purposeful practice’. Purposeful practice consists of the following principles:

- Purposeful practice has to be focused. You should not be able to think of your next meal (nuggets!) while undertaking it.

- Purposeful practice should take you out of your comfort zone. It should feel painful to do. As I’ve mentioned earlier, playing a piece of music you already know how to play — for instance, during a musical performance — does not count, and writing a program that utilises techniques you already know to use also does not count for the purpose of mastery. Practice that makes you better should take maximal effort, and thus feel terribly unpleasant to do.

- Purposeful practice requires feedback, and adjustments to technique after getting the feedback. In its most general form, Ericsson notes that feedback need not be immediate — but it is most effective if the feedback loop is short.

- Purposeful practice has well-defined, specific goals. You don’t want to “play this musical piece”, you want to “play the complicated second section that requires unorthodox finger placement”. You don’t want to “code iPhone apps” you want to “implement the nested MVC model from scratch”.

Deliberate practice, on the other hand, adds a small number of principles to the above collection:

- First, it demands that the practice be conducted in a field with well-established training techniques. Fields like music, math and chess have rigorous training methods that have been developed over the course of decades. This makes such fields ideal candidates for deliberate practice.

- Second, it demands that practice be guided in the initial stages by a teacher or coach. This is somewhat linked to the first principle — that the practice occurs in a domain with established training methods mean that a teacher may use known pedagogical techniques to improve student performance. As the student improves, her ability to form accurate mental models will also improve; these models allow her to eventually practice on her own.

- Third, and last, deliberate practice nearly always involves building or modifying previously acquired skills by focusing on particular aspects of those skills and working to improve them specifically. This in turns implies finding teachers or coaches with ever higher levels of expertise, and learning better refinements from them.

In other words, by Ericsson’s definition — or at least, according to the one that I’ve taken from Peak — if you are in a domain with little known training methods, you cannot do deliberate practice in its pure form. You cannot do so because you would need to discover effective mental models yourself. You would also have to develop training methods of your own, as no standardised methods exist. These restrictions puts you firmly in the domain of purposeful practice alone.

Is all hope lost? Not exactly. Many of us work in domains with ‘fractionated’ pools of expertise. For instance, I am a computer programmer by training. My domain consists of many higher order skills like distributed systems design, or ‘the skill of implementing 20% of what the client asked but delivering 80% of the value, while pretending to be doing 100% of what the client asked for and delivering 100% of the value’ — for which no standardised training methods exist. But it also contains topics like ‘testing’, or ‘object oriented programming’ or ‘database modelling’ for which established training methods do exist. We may apply purposeful practice to the former, and seek out opportunities for deliberate practice for the latter.

What problems exist for practice in fields where no good training methods exist? Elsewhere in this blog I’ve mentioned that I taught myself to write using deliberate practice methods over the course of 10 years; more recently I applied it to the practice of management. From this experience, the main challenges are:

First, the problem of ill-defined sub skills. Deliberate practice requires you to break your domain down into sub skills, and then train these sub skills systematically. Often sub skills are dependent on other sub skills; a self learner would have to figure out the dependencies on her own. To put this another way, a self-taught learner essentially has to do ‘skill extraction’ and syllabus design, both of which are discrete skills themselves. I talk about skill extraction in Part 5 of my framework for putting mental models to practice. Syllabus design techniques, on the other hand, can be learnt from pedagogical books; the one that I like most (because I am a programmer by training) is Chapter 6 of Teaching Tech Together. (Note: this requires reading chapters 2 through 5 for a proper background, but the chapters are really short and fun to read). Max Deutsch’s blog post on creating his crossword puzzle training program is also an instructive read on one person’s skill-extraction and syllabus design — Deutsch is really quite the remarkable self learner!

Second, the difficulties that emerge from lack of feedback. Self-learning means lack of feedback from a teacher, which means substituting feedback gained via other methods. This demands great creativity. Ericsson mentions that a common training technique used by chess players is to study a chess position from an actual game, and then attempt to make the next move as a grandmaster would. If the student finds that her chosen move differs from the actual move made by the grandmaster, she would go back to analyse what she missed. This technique may also be deployed for other skills; Ericsson suggests summarising a passage you admire and then reproducing it as closely as possible to the original, observing the differences you make after you are done. It was in this way that Benjamin Franklin taught himself to write.

There are other methods, of course. One way is to use spaced repetition software like Anki to train recall; another is to record yourself in a performative activity (e.g. playing the piano, football, but even writing and learning a foreign language!) and reviewing the footage for clues. In Part 4 of my framework I propose using ‘difficulty of a class of problems one faces at work’ to judge progress on a specific domain.

Third, the problems that result from a lack of opportunities for practice. In work environments, lack of experience is often a gotcha. I document a simulation technique called ‘decision making exercises’ or DMXs in Part 5 of my framework for putting mental models to practice, but I recommend buying and reading The Power of Intuition, which covers these techniques in far greater detail.

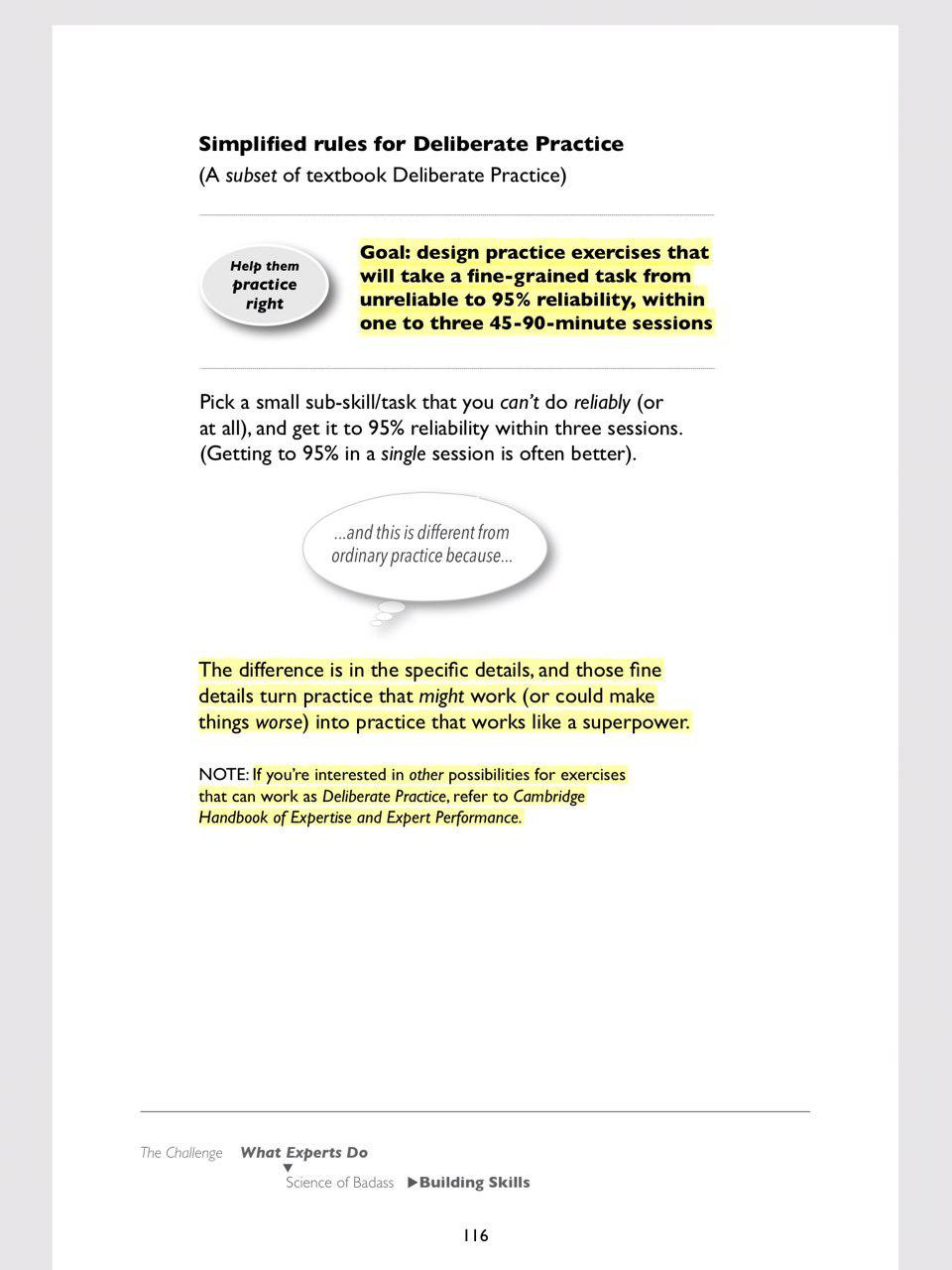

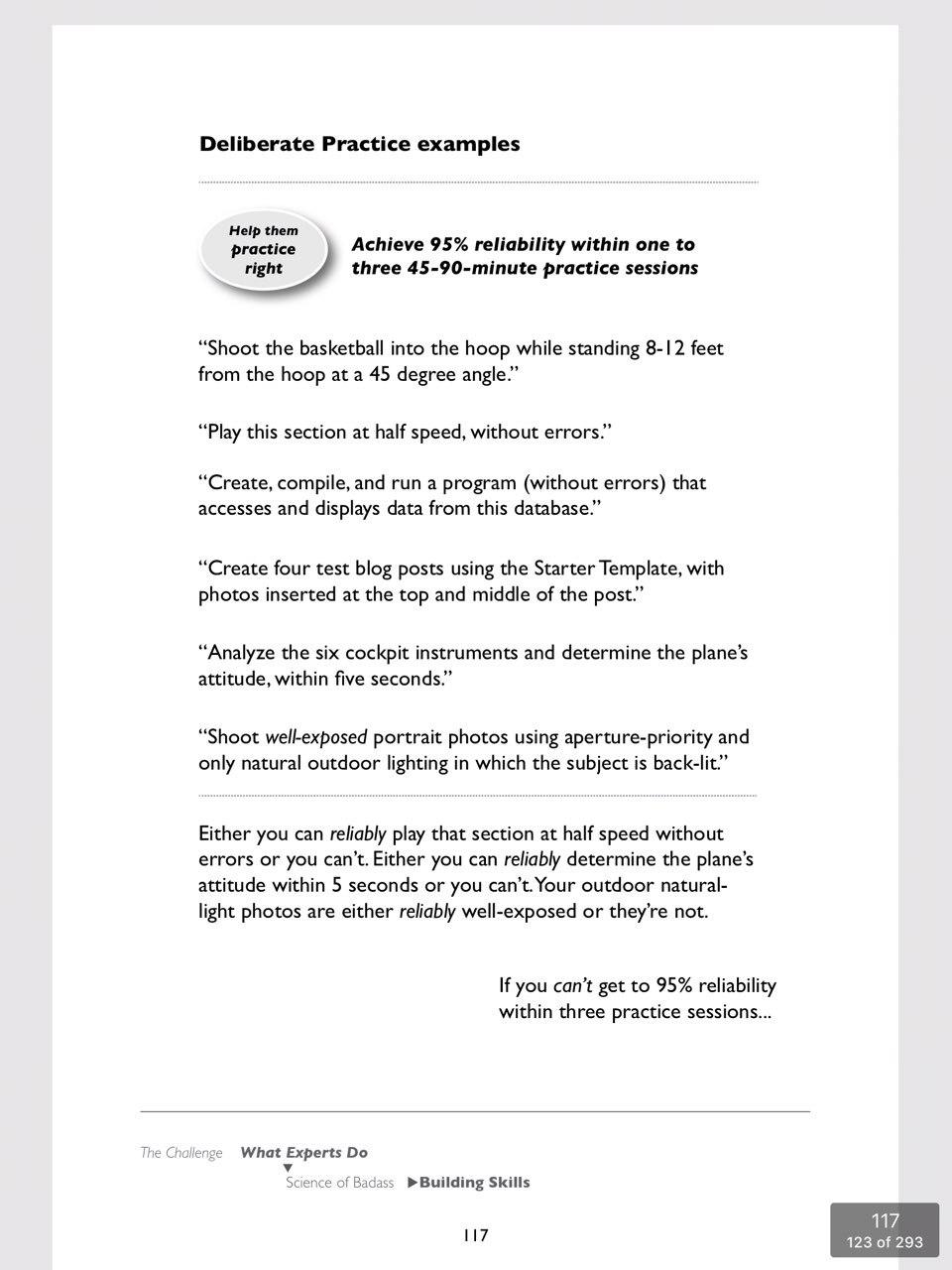

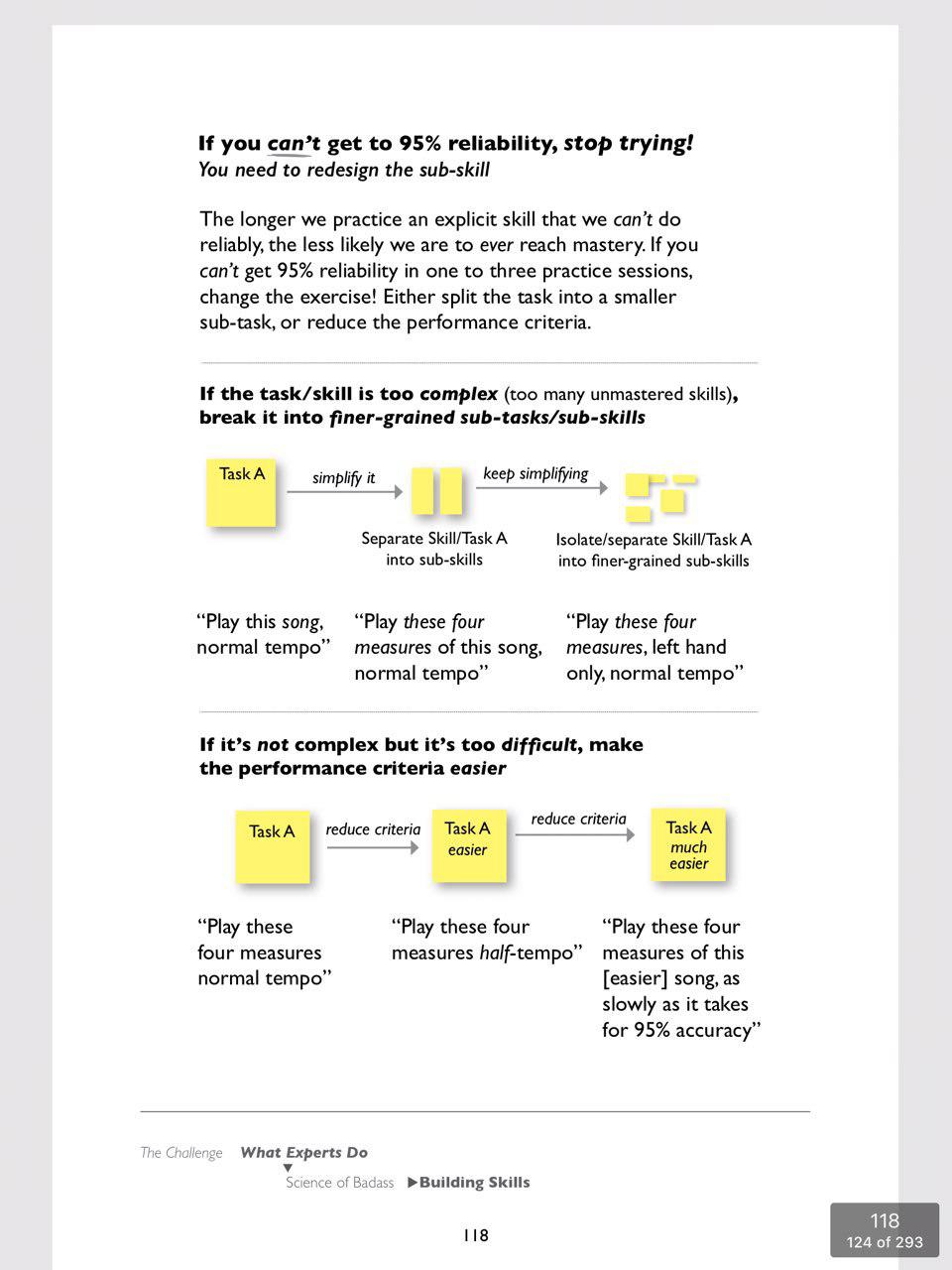

Fourth, a lack of feeling of progress or a lack of motivation — this is related to the first two problems above, because of the nature of human learning. We can only learn skills we are ready to learn, so if we lack a coach we will often plateau due to an inability to pick the right-sized sub skill, in the right order. The best remedy for this that I’ve found (so far) is the prescription from Kathy Sierra’s Badass: Making Users Awesome which gives a simpler form of deliberate practice, see screenshots below:

In sum, applying deliberate practice in service of our careers is way more challenging than Ericsson makes it appear. I find myself continuously struggling when putting his ideas to practice, and I really dislike the hundred and one self-help blog posts that parrot his findings without attempting to apply them. Deliberate practice in the sorts of skills that we rely on in our careers is hard, because coming up with effective training methods is hard.

Expect to see more blog posts on Commonplace on this topic, as I experiment with different methods for putting deliberate practice to practice in my life.

Note (8 Sep 2021): I've since found a body of work that sidesteps the problems of putting deliberate practice to practice — see here and here.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→