I have a friend who’s currently doing a PhD in Artificial Intelligence. Last year, when he was back in Singapore, he went over to the Nanyang Technological University to give an hour-long talk on his recent work. NTU is located far in the west of Singapore, tucked into a bit of no-man’s land; my friend came back six hours later, exhausted but happy.

“What took you so long?” I asked, because we had dinner plans with other friends, and his delayed return meant that he couldn’t join.

“Oh, the PhD students who attended wanted to talk about the meta. And then I lost track of time.”

*

Every sufficiently interesting game has a metagame above it. This is the game about the game. It is often called ‘the meta’.

Sometimes, the metagame is created when new options are introduced from outside the game. Magic The Gathering is famous for having a game system that changes every time the publisher releases a new set of cards. MtG’s metagame is thus a race to see who can discover new card combinations or strategies given the new options. The players who do so are rewarded with easier wins, especially when going up against players who have not adapted to the new possibilities. This makes MtG a game of two levels: the first game is the game you’re playing when you sit down and shuffle cards to battle an opponent; the second game is the race to acquire, analyse and adapt to new cards quicker than your competition.

Metagames like MtG’s also exist in, erm, more physical games. Judo — the sport that I am most familiar with — has a metagame that is shaped by rule changes from the International Judo Federation. A few years after I stopped competing, the IJF banned leg grabs, outlawing a whole class of throws that were part of classical Judo canon — many of them used regularly, even at the top levels of competition. The Judo that exists today is very different from the Judo I left — with changes in gripping strategy, entry styles, and technique combinations — many of them responses to responses to responses to the ruling.

These ‘response chains’ characterise another type of metagame. Some games don’t have changing rules, and are free from an overwhelming supply of new possibilities. In such games, the meta changes when competitors act within the space of possibilities of a static game system.

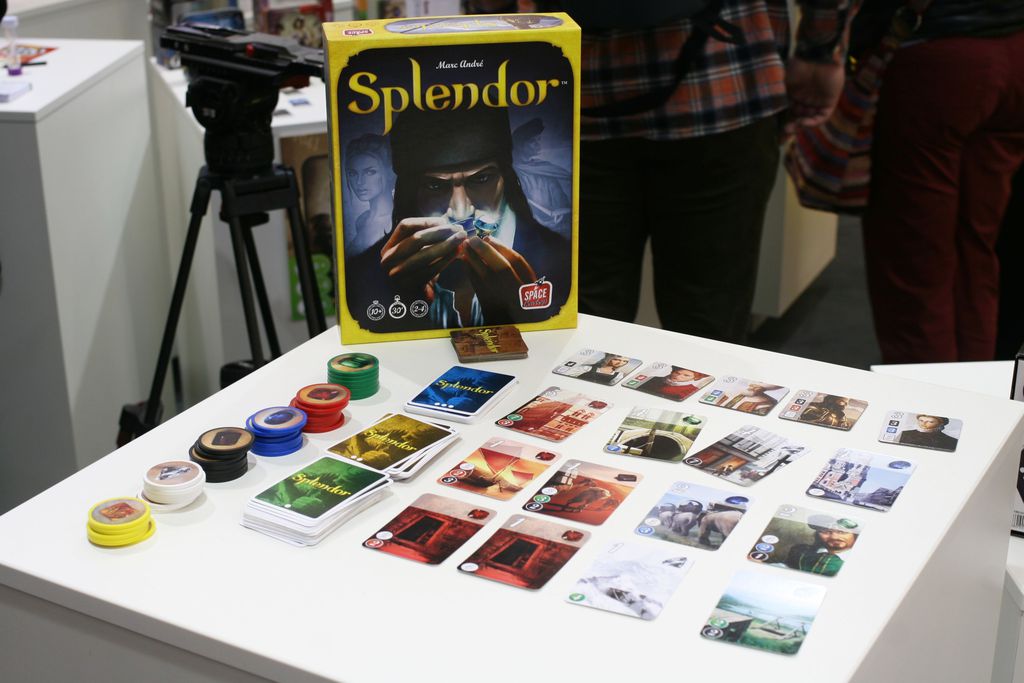

An example of this is the excellent board game Splendor. Players buy expensive cards to earn victory points, using poker chips acquired from a central pool. Cheaper cards carry no points but give you a discount on future purchases. The most obvious strategy when you start out in Splendor is to build an ‘engine’ — that is, a tableau of cheap cards that provide you with a large number of discounts, after which you can go after higher-priced, higher-point cards, and win.

The metagame in Splendor emerges the instant someone figures out that you can skip on buying cards for discounts, save up on chips, and go directly after the more expensive cards with points. Once a player makes this discovery, Splendor changes for the better. It becomes a fluid game of blocking, reserving, purchasing and adapting — with most players doing a combination of ‘building’ and ‘buying’ in response to what everyone else is doing around them.

Splendor is a good example because there are only two major approaches in the game, and sufficiently competitive gaming groups will discover both of them in a matter of days. But the optimal strategy in Splendor will continue to shift back and forth as a hybrid of the two strategies, depending on the player mix and the changing preferences of the players within your gaming group.

As it is with games, so it is with life.

The Meta In Real Life

Every sufficiently interesting domain in the world has a meta associated with it.

Like simpler games, real-world metas come in roughly two flavours: ones that are defined by external changes to the rules of a game, and ones that are shaped by a dynamic equilibrium of competition within a stable system of play. Unlike games, however, real-world domains have no set rules: they are vastly more complicated and interesting, because the rules change only when someone notices the rules have changed.

Here’s a real world example.

I’ve spent the last two years working to get better at marketing. If you’re reading this blog, you’ve probably observed the evolution of my content marketing skills first hand. (I grade myself a C+, but more on this in a bit).

Anyone who attempts to become really good at marketing must learn the same handful of basic ideas: amongst them, the concept of a funnel and how to measure it, the idea of the buyer’s journey, and the ability to construct and use buyer personas … even if done unrigorously. (The idea of the persona is more important than the form of the persona itself. I know one or two self-taught marketer/entrepreneurs who have an intuitive — and effective! — conception of their ideal buyer in their heads, but are unable to articulate it properly when asked).

Above these basics are channel-specific skills. These are tactical things: some marketers are better at email marketing, others at content, still others are better at ad-buys and social media. A valuable subset of marketers are able to take an entire team and scale it up for a specific type of product. Whichever it is, these skills are deep and context-specific. Good practitioners know the ‘best practices’ for their specific channels. The better practitioners keep up with the evolution of those best practices. The best marketers … well, the best marketers play the metagame of marketing.

The metagame of marketing emerges from the fact that all marketing channels decline in efficiency over time. To hear the veterans tell it, Google Adwords in the early 2000s was like shooting fish in a barrel. By the 2010s, Adwords had become prohibitively difficult and expensive — its costs driven up by mainstream adoption and increased competition. Similar stories have played out in the Facebook-owned ad ecosystem (think: Facebook, then Instagram, then Instagram stories). The best marketers are therefore the ones who advance the best practices the fastest to keep ahead of the mainstream, or are able to identify and develop playbooks for new channels before the old ones become too inefficient to fight in. The quicker they identify new channels and the longer they keep their playbooks secret, the better the marketing game becomes for them.

In this way marketing’s meta is much like MtG’s.

Business also has a meta. Take acquisitions, for instance. Companies have acquired other companies since the beginning of companies — but the game through which this happens has changed significantly over the years.

Henry Singleton, the CEO of Teledyne, famously used share issuances in the 60s to fund Teledyne’s many acquisitions, eventually building it into one of the most valuable conglomerates in America. He then pioneered the use of the share buyback to purchase Teledyne stock cheaply during the bear markets of the 70s, eventually repurchasing 90% of all outstanding shares — including the ones he had issued at high prices in the preceding decade. Investor William Thorndike says that Singleton’s track record is in ‘a completely different zip code’ when compared to famous contemporary CEOs like Jack Welch: GE under Welch outperformed the S&P 3.3 times; Teledyne under Singleton outperformed the S&P over 12 times during his tenure as CEO.

Singleton’s playbook changed the rules of business in ways that still echo today — for instance, share buybacks were treated with derision during Singleton’s time, but are today considered standard entries in the corporate finance playbook. Much later, parts of Singleton’s capital allocation strategy was adapted to a different context by a young man named Warren Buffett, who applied it to an ailing textile manufacturing company named Berkshire Hathaway.

In the late 70s, the meta changed again. A man named Michael Milken pioneered the use of an obscure financial instrument called the high-yield bond, more popularly known as the ‘junk bond’. He quickly realised that these junk bonds could be used to raise immense amounts of capital for the purpose of corporate takeovers, with little to no cost to the acquiring company. Such ‘leveraged buyouts’ (LBOs) — which issued debt on the target company’s assets, not on the parent company’s books — changed the rules of the takeover game in ways that persist till today. The players that emerged to take advantage of this innovation, the ones who skated to the edge of the meta? We know them today as private equity firms.

The meta in business changes whenever new tools or opportunities emerge in the macro environment. New tools mean new options. New options mean new viable strategies. The Koch brothers adapted pieces of Milken’s LBO playbook when they began expanding their energy empire in the 80s; today, the private equity world is adapting those strategies to survive in a world of excessively cheap capital. The meta changes yet again in response to macro conditions — and on it goes.

The Meta as a Test of Expertise

What is interesting about the meta is that metagames can only be played if you have mastered the basics of the domain. In MtG, Judo, and Splendor, you cannot play the metagame if you are not already good at the base game. You cannot identify winning strategies in MtG if you don’t do well in current MtG; you cannot adapt old techniques to new rules if you don’t already have effective techniques for competitive Judo.

What is true in sports is also true in real world domains like marketing and business; it is true even if you are aware of the meta’s existence. The nature of the metagame demands that you play the base game well. It lives on top of the pattern-matching that comes with expertise.

This seems like an obvious thing to say. But as with most such things, the second-order implications are more interesting than the first-order ones. For instance, because expertise is necessary to play the metagame, it is often useful to search for the meta in your domain as a north star for expertise. The way I remind myself of this is to say that I should ‘locate the meta’ whenever I’m at the bottom of a skill tree. Even if I can’t yet participate, searching for the metagame that experts play will usually give me hints as to what skills I must acquire in order to become good enough.

An example suffices: in marketing, I have found it very useful to seek out articles or podcasts (but especially podcasts) where practitioners talk about the ways their best practices have changed: “In the past I did X and now it seems it doesn’t work as well, so now we do Y, and I recommend Y.” This tells me that:

- I need to learn Y and at least have a passing familiarity with X, because X is what came before and is ‘covered ground’, and

- I need to remember the ‘shape’ of the shift. If one such shift happened in the past, more may happen in the future.

More concretely, this is something like a podcast guest saying:

“In the past (for content marketing) I did roundup posts, but these don’t seem to work as well anymore. So now we do longer, more comprehensive guides, and we cross-launch those to Product Hunt and Hacker News and social media. That seems to work better for us.”

Which in turn tells me:

- I need to look up as many examples of these ‘comprehensive guides’ to see what the state of the art looks like. From there I can develop an understanding of how they are planned, how they are executed and what success looks like when these things are launched. And I must launch one to verify their effectiveness for myself.

- I need to try my hand at at least one roundup post, just for the tacit experience of doing it.

- And I must ask: why did roundup posts fail? Well, because too many people are doing it. (Is this true? How do I verify?) Why might the current best practice fail, then? I might not know the answer to this because I am a noob, but a side-effect of (1) is that I now know the best practitioners of the guide strategy, and I can observe them to see what changes in their marketing over the next few years.

Note what I’m not saying, however. I’m not saying that I should actively pursue the meta — this is ineffective, because I am not good enough to play. I cannot execute even if I know where the puck is going. But studying the state of the metagame as it is right now often tells me what I must learn in order to get to that point.

(This is, by the way, where my self-grading comes from — I look to the marketers who are playing at the edge of the meta, and I rate myself a C+ in comparison. The ability to make such comparisons is in itself useful).

James Stuber has this thing where he says “master boring fundamentals”, and he says it in response to beginners who desire to go after the fancy stuff. Stuber’s quip applies here. To run with his terminology: I’d say that the meta is what you get after you master boring fundamentals. But observing the state of the current meta often reveals what boring fundamentals you need to learn.

This is particularly useful if your skill tree has no set syllabus. It is especially useful when you don’t have a coach.

Get to the Meta For One Skill

How do you balance between locating the meta and chasing boring fundamentals? The short answer to that is to do trial and error. If you can’t master a particular skill, drop back down to its component elements and practice each of them in isolation. If you don’t get good conversions in your content marketing, drop down to practice publishing at a regular cadence. If you can’t get a throw to work, break it down to arms, then legs, then body position, then into one complete motion.

How do you learn to do this? I think the best way to do so is to get good at a single, well-structured skill … and preferably, to get this experience as early as possible in one’s life.

I’ve noticed that the ‘feel’ of improving in pursuit of a meta is strangely similar across skill trees. I noticed this after climbing high enough in the Judo skill tree to see the meta for the first time. Later, when I moved to university, learning the craft of programming became slightly easier. Ditto for content marketing, and email marketing, and so on.

I don’t know if it is identifying the meta that helps, or if there is some other deep skill transference that’s going on. But I’ve cautiously reached out to friends who have played serious competitive sports when they were younger, and many of them have had similar experiences. There seems to be something in getting good at a skill tree that helps in latter life. I’d like to think it is a function of exposure: once you see the competitive meta at the top of one skill tree, you begin looking for it everywhere else.

*

My closest cousin is a software engineer. Recently, his frontend engineering team hired a former musician: someone who had switched from piano to Javascript programming with the help of a bootcamp. He noticed immediately that her pursuit of skills (and the questions she asked) were sharper and more focused than the other engineers he had hired. He thought her prior experience with climbing the skill tree of music had something to do with it.

My cousin plays ultimate frisbee on the side. To hear him tell it, the metagame in frisbee is more like Splendor: within an unchanging rule system, the dominant strategies are always an adaptation to what your opponent is doing. These strategies sit atop basic throwing and receiving skills. Sometimes, if the opportunity arises, if you understand the metagame well enough, and if you are lucky, your team can get really creative with responses. My cousin loves Ultimate — when he talks about it his eyes light up and he begins gesticulating. It is for him as Judo was for me.

When we meet, we talk about the meta a lot because we see parallels between our sports and our respective careers. My cousin has this theory that the people who get really good at one skill will find it easier to get good at a second skill. I believe him. Our experiences bear this out.

(Related: Tobi Lutke offers former pro StarCraft player a job at Shopify; this fun piece then analyses Lutke’s strategy as CEO of Shopify through the lens of StarCraft, although it’s clear that the author doesn’t grok StarCraft’s meta at all).

My cousin and I both want our kids — when we have them — to get good enough to play in a metagame for one skill, any skill, in whatever game strikes their fancy. It could be Ultimate or Judo or tennis or chess. It could be Fortnite and Dota, if those things still exist when they’re old enough.

The important thing is exposure to the meta. My cousin and I both think this exposure is fundamental. We think this because metagames really do exist everywhere in life; you just have to know how to look.

Get the Action Sheet

Download the actionable summary for To Get Good, Go After The Metagame here →

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→

This article is part of the Market topic cluster, which belongs to the Business Expertise Triad. Read more from this topic here→