This is Part 5 in a series on tacit knowledge. Read Part 4 here.

Let’s say that you’re a junior employee at a company, and you find a senior person with a set of skills that you’d like to learn. You ask them how they do it, and they give you an incomprehensible answer — something like “oh, I just know what to do”, or “oh, I just do what feels right”. How can you learn their skills?

In Part 2 of my tacit knowledge series, I described one method: you take something called the recognition-primed decision making (RPD) model and then you use that as a map to get at the tacit expertise of skilled practitioners around you. The RPD model describes how intuitive expertise works; my argument was that once you understand the shape of intuition, you can get at some of the things that every expert must do when they’re operating in the real world, even when they can’t explain what they do.

The main problem with that approach is that it's really hard. While RPD describes what expert intuition is, it doesn’t really help you extract that intuition for yourself. The researchers who came up with the RPD model developed a method for doing that, which they named the ‘Critical Decision Method’ (CDM), but the technique is incredibly difficult to learn and extremely time consuming to execute. All of which is well and good when you’re a researcher, and your clients hire you to spend months designing training programs for them; less so if you’re a practitioner, and you simply want to get at the skills that live in other peoples’s heads.

Which brings us to this post.

In 1998, Laura Militello and Robert Hutton published a landmark paper titled Applied Cognitive Task Analysis (ACTA): A Practitioner’s Toolkit for Understanding Cognitive Task Demands. The paper’s contribution was a set of four techniques that are much easier to use than CDM (and other related methodologies), and yet powerful enough for instructional designers or interface designers to extract tacit mental models of expertise from the heads of subject matter experts for their use. The work was funded by the Navy Personnel Research and Development Centre and lasted two years; the authors tested the usability of these new methods by teaching them to two groups of graduate students, before letting them loose to interview two sets of experts: fireground commanders on one end, and naval electronic warfare specialists on the other. These graduate students were then asked to modify existing training programs for both domains, after which those modifications were evaluated by expert instructors in the field.

Militello and Hutton’s reasoning went something like this: if ACTA was easy enough for random graduate students to use, and if it resulted in significant improvements to the training programs in both domains, then the methods would be even more effective when put in the hands of domain-specific course creators and interface designers. The authors knew that ACTA wasn’t as accurate or as powerful as earlier research methods (like CDM), but they thought that the simplicity of their technique was a worthwhile tradeoff.

In the years since they first published the paper, they’ve largely been proven right. Which probably means that it is worth it for us to take a look at their methods, in order to adapt them to our goals.

The Four Techniques of Applied Cognitive Task Analysis

There are four techniques in ACTA, and all of them are pretty straightforward to put to practice:

- You start by creating a task diagram. A task diagram gives you a broad overview of the task in question and identifies the difficult cognitive elements. You'll want to do this at the beginning, because you'll want to know which parts of the task are worth focusing on.

- You do a knowledge audit. A knowledge audit is an interview that identifies all the ways in which expertise is used in a domain, and provides examples based on actual experience.

- You do a simulation interview. The simulation interview allows you to better understand an expert’s cognitive processes within the context of an single incident (e.g. a firefighter arrives at the scene of a fire; a programmer is handed an initial specification). This allows you to extract cognitive processes that are difficult to get at using a knowledge audit, such as situational assessment, and how such changing events impacts subsequent courses of action.

- You create a cognitive demands table. After conducting ACTA interviews with multiple experts, you create something called a ‘cognitive demands table’ which synthesises all that you’ve uncovered in the previous three steps. This becomes the primary output of the ACTA process, and the main artefact you’ll use when you apply your findings to course design or to systems design.

We’ll go through each technique in turn.

Task Diagram

The goal when creating a task diagram is to set up the knowledge audit and the simulation interview. You want a big-picture overview of the most cognitively demanding parts of the task, so that you may focus the majority of your time on those parts.

You start out by asking the expert to decompose the task into steps or subtasks. You ask: “Think about what you do when you (task of interest). Can you break this task down into less than six, but more than three steps?” The goal is to get the expert to walk through the task in his or her mind, verbalising the major steps. The question purposely limits the expert to between three and six steps to ensure that they don’t waste time diving into minute detail; you really want to prevent yourself from digging into their mental models at this stage.

After the expert settles on a list of steps, ask: “Of the steps you have just identified, which require difficult cognitive skills? By cognitive skills I mean: judgments, assessments, and problem solving-thinking skills.”

Circle those steps; you’ll be focusing on them during the next two techniques.

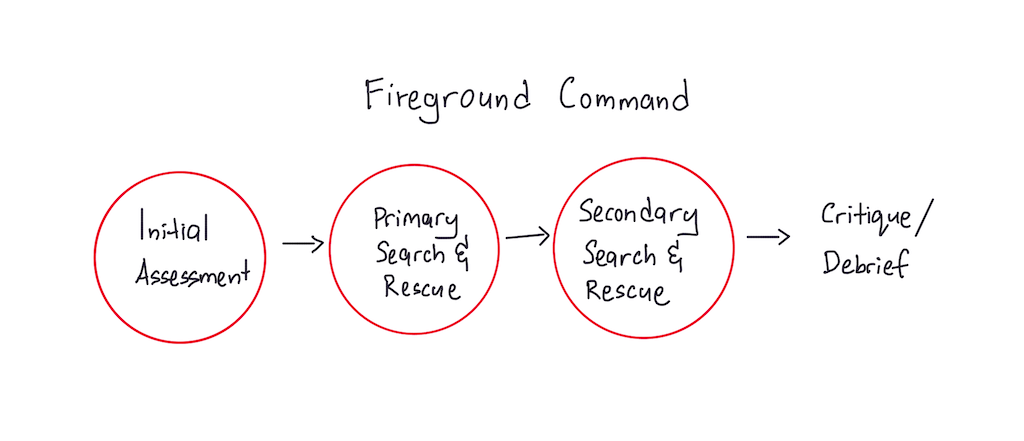

The output of the task diagram would look something like this:

In this case, you’ll expect to dive deep into ‘Initial Assessment’, ‘Primary Search and Rescue’, and ‘Secondary Search and Rescue’, and ignore the ‘Critique/Debrief’ step.

Knowledge Audit

The knowledge audit identifies ways in which expertise has been used in a domain, and surfaces examples based on the expert's real world experiences. The goal here is to capture the most important aspects of expertise.

You start out with a list of basic probes. These probes are drawn from the knowledge categories that most commonly characterise expertise. After a handful of interviews, it should become clear to you which probes produce the most information for that specific subtask; you may then reduce the time you spend on less useful questions.

Here's a full list of basic probes:

Basic Probes

- Past & Future — Experts can figure out how a situation developed, and they can think into the future to see where the situation is going. Amongst other things, this can allow experts to head off problems before they develop. “Is there a time when you walked into the middle of a situation and knew exactly how things got there and where they were headed?”

- Big Picture — Novices may only see bits and pieces. Experts are able to quickly build an understanding of the whole situation — the Big Picture view. This allows the expert to think about how different elements fit together and affect each other. “Can you give me an example of what is important about the Big Picture for this task? What are the major elements you have to know and keep track of?”

- Noticing — Experts are able to detect cues and see meaningful patterns that less-experienced personnel may miss altogether. “Have you had experiences where part of a situation just ‘popped’ out at you; where you noticed things going on that others didn’t catch? What is an example?”

- Job Smarts — Experts learn how to combine procedures and work the task in the most efficient way possible. They don’t cut corners, but they don’t waste time and resources either. ”When you do this task, are there ways of working smart or accomplishing more with less — that you have found especially useful?”

- Opportunities/Improvising — Experts are comfortable improvising — seeing what will work in this particular situation; they are able to shift directions to take advantage of opportunities. ”Can you think of an example when you have improvised in this task or noticed an opportunity to do something better?”

- Self-Monitoring — Experts are aware of their performance; they check how they are doing and make adjustments. Experts notice when their performance is not what it should be (this could be due to stress, fatigue, high workload, etc) and are able to adjust so that the job gets done. ”Can you think of a time when you realised that you would need to change the way you were performing in order to get the job done?”

Optional Probes:

- Anomalies — Novices don’t know what is typical, so they have a hard time identifying what is atypical. Experts can quickly spot unusual events and detect deviations. And, they are able to notice when something that ought to happen, doesn’t. ”Can you describe an instance when you spotted a deviation from the norm, or knew something was amiss?”

- Equipment Difficulties — Equipment can sometimes mislead. Novices usually believe whatever the equipment tells them; they don’t know when to be skeptical. “Have there been times when the equipment pointed in one direction, but your own judgment told you to do something else? Or when you had to rely on experience to avoid being led astray by the equipment?”

These probes act as the starting point for conducting the knowledge audit interview. After opening with each probe, you ask for specifics about that example, focusing on critical cues and strategies that the expert employs. Then, you follow up with a discussion of potential errors that a less-experienced person might have made in the situation.

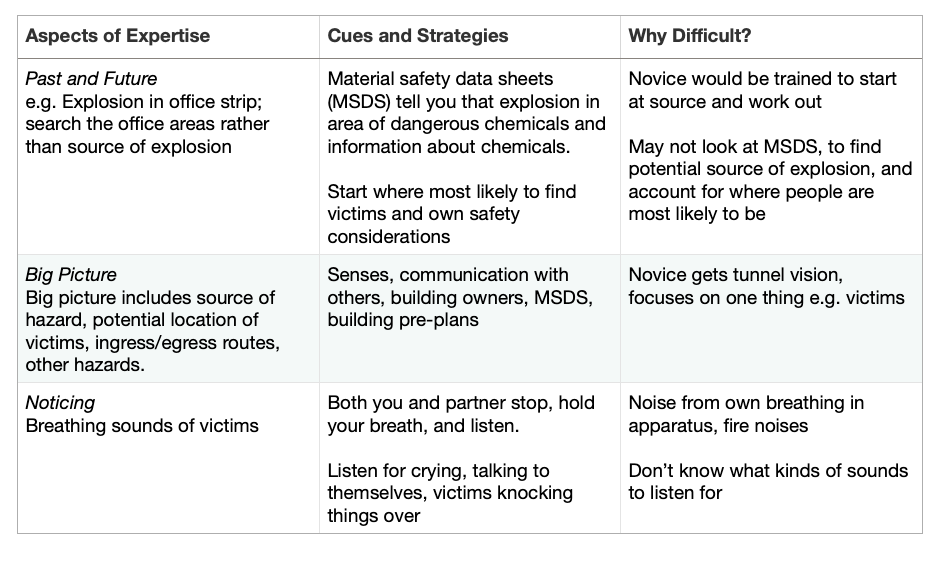

What you should expect to get out of the knowledge audit is a table like this:

Simulation Interview

Next up is the simulation interview. Whereas the knowledge audit is designed to elicit cues and strategies in the context of real-world examples from the expert’s past experience, the simulation interview is built around the presentation of a challenging scenario to the expert. Militello and Hutton write:

The authors recommend that the interviewer retrieves a scenario that already exists for use in this interview. Often, simulation and scenarios exist for training purposes. It may be necessary to adapt or modify the scenario to conform to practical constraints such as time limitations. Developing a new simulation specifically for use in the interview is not a trivial task and is likely to require an upfront CTA (cognitive task analysis) in order to gather the foundational information needed to present a challenging situation. The simulation can be in the form of a paper-and-pencil exercise, perhaps using maps or other diagrams. In some settings it may be possible to use video or computer supported simulations. Surprisingly, in the authors’ experience, the fidelity of the simulation is not an important issue. The key is that the simulation presents a challenging scenario.

Of the four techniques in ACTA, picking a good simulation seems like the trickiest part of the methodology. I wish I could be of more use here — I spent half an hour googling for guidance in the Naturalistic Decision-Making literature, but couldn’t find a generalised list of tips on picking a good simulation. I suppose you’ll have to experiment to figure out what works best for your unique skill domain; the key thing about simulations is that they are usually a series of events that occur, and must be revealed one at a time in order to — as the authors put it — present a challenging scenario to the expert.

The general flow of the simulation interview goes like this: you present the first part of the simulation to the expert (e.g. describe the initial setup, or give them a brief, etc), and then you prompt the expert to identify major events, including judgments and decisions, with a question like “As you experience this simulation, imagine you are the (job you are investigating) in the incident. Afterwards, I am going to ask you a series of questions about how you would think and act in this situation.”

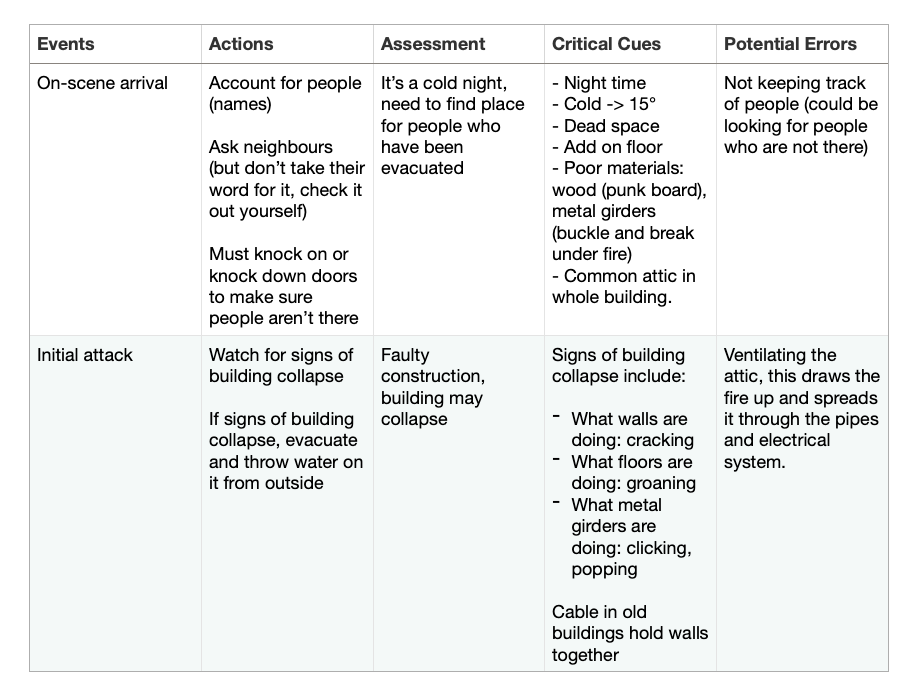

Each event in the simulation is then probed for situation assessment, actions, critical cues, and potential errors surrounding that event. You record this information in a ‘simulation interview table’, which looks like this:

You’ll want to redo the simulation interview with multiple experts, since different people may provide insight into situations in which more than one action would be acceptable, and alternative assessments of the same situation are plausible. You could even use the technique to contrast expert and novice perspectives by conducting the same simulation interview with people of differing levels of expertise.

The goal, once again, is to get at the expert’s cognitive processes within the context of an incident. If you combine the results of the simulation interview with the knowledge audit, you should get a pretty good sense of the types of expertise at play.

Cognitive Demands Table

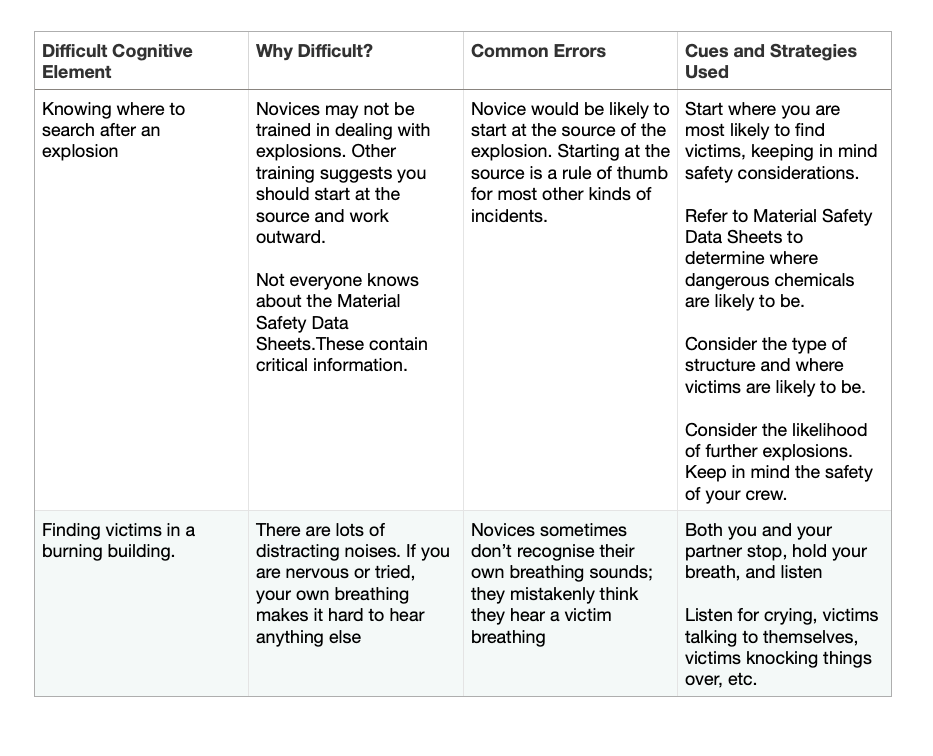

The final technique in the ACTA arsenal is a presentation format that lets you sort through and analyse the data. This is known as a ‘cognitive demands table’, and it's the final artefact that is produced at the end of the ACTA process, for use in your project.

The cognitive demands table presented below is taken from analyses that Militello and Hutton have conducted in the past. They say that you should pick different table headings, depending on the types of information that you would need to develop a new course or design a new system (or, in our case, learn skills that live in the heads of experts around us) — whatever it is that you want to do. More importantly, filling up the table should help the practitioner spot common themes in the data, as well as conflicting information given by multiple experts.

And it looks like this:

Wrapping Up

Applied Cognitive Task Analysis seems easy enough to use. Of course, the caveat here is that the method was designed for use in instructional design, or systems design, not necessarily for extracting the tacit mental models of expertise of the people around us for the purposes of individual learning.

But I think it's possible to adapt it to those ends.

As it happens, I’m currently doing a repositioning exercise for a SaaS product, using April Dunford’s Obviously Awesome as a template for execution. Part of that exercise involves working alongside salespeople and getting at the expertise in their heads. If you're in sales, you probably have a good sense for what customers want. And that in turn means that there's something there for marketing to use.

All this is to say that I can't wait to put ACTA to the test. And when I'm done with that, I’ll let you know how it goes.

Read Part 6 — The Tricky Thing About Creating Training Programs. You may also read John Cutler’s Product Org Expertise, which features ACTA.

Originally published , last updated .