I consider Tiago Forte to be one of the best, most effective thinkers in productivity today. A few years ago, he wrote a particularly good introduction to the Theory of Constraints. I quote:

The Theory of Constraints is deceptively simple. It starts out proposing a series of ‘obvious’ statements. Common sense really. And then before you know it, you find yourself questioning the fundamental tenets of modern business and society.

Forte goes on to explain the collection of ‘obvious’ statements:

- Every system has one bottleneck that’s tighter than all the others.

- The performance of the system as a whole is limited by the output of the tightest bottleneck or most limiting constraint.

- The only way to improve the overall performance of the system is to improve the output at the bottleneck (or more broadly, the performance of the constraint).

These obvious statements are obvious, but then Forte points out that they lead you to a less obvious conclusion: if you’re trying to improve a system, effort spent on improving anything that is not the bottleneck is essentially wasted effort.

Forte works out the full implications of this single idea over the course of his series. It’s a thrilling read, like watching a Lego builder putting together a sculpture from the simplest possible building blocks.

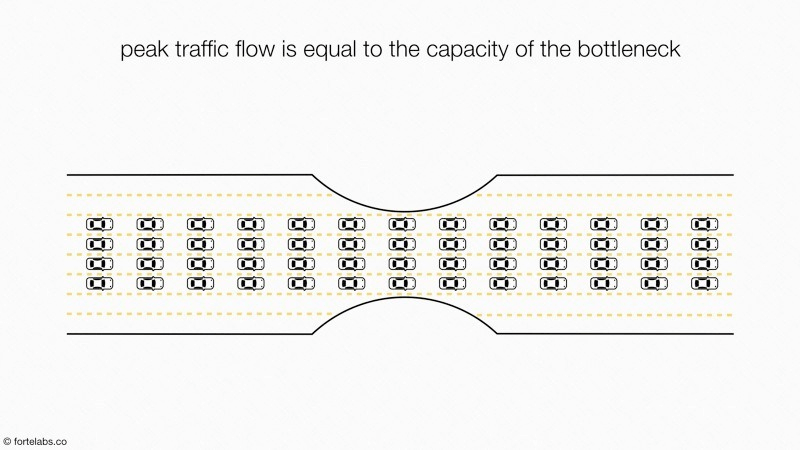

One other non-obvious implication, introduced in Part 4, is the notion that in order to achieve efficiency, peak workflow should always be equal to the capacity of the bottleneck.

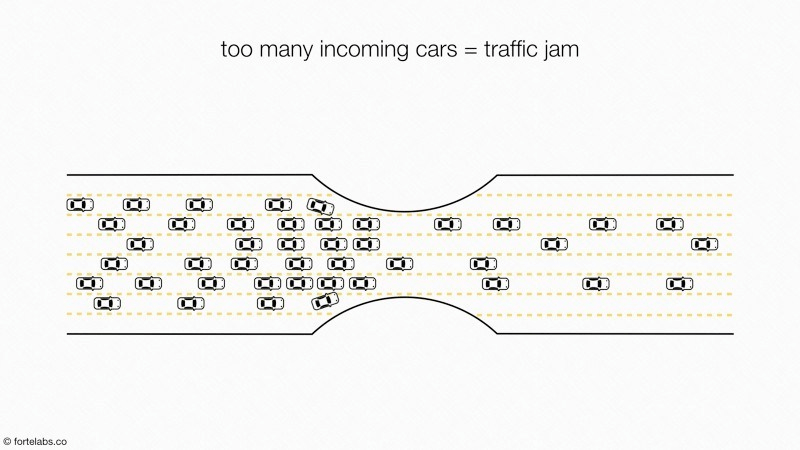

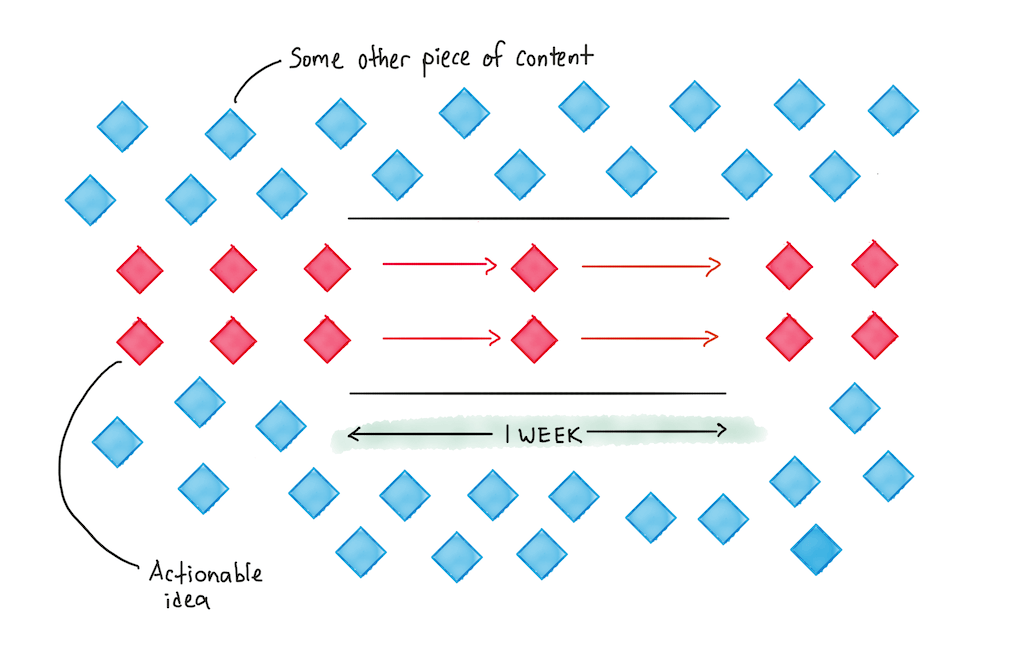

This sounds a bit complicated, but it is actually really easy to grok when you look at Forte's illustrations:

In the first picture, too many incoming cars at a bottleneck causes a traffic jam. This is similar to production, where inputs that outstrip the capacity of the tightest production step will cause inefficiencies in the entire production process. These inefficiencies usually emerge in the form of inventory build-up (which leads to the added busy-work of inventory management — a type of waste, or ‘muda’ as Taiichi Ohno puts it!), or in some other form of overhead, like increased process complexity, unnecessary transportation, or workers hanging around, waiting.

So what do you do about this problem? You have two options:

- You increase the capacity of the bottleneck.

- You limit the throughput of the inputs.

Whichever method you pick, the outcome turns out to be same: peak efficiency only occurs when the inputs match the capacity of the bottleneck. I remember reading this and going: “holy crap, this is subtle, useful stuff!”

And then, several months later, I realised I should be applying this to my reading life as well.

We Often Read More Than We Can Do

I think many of us — bright, career-oriented knowledge workers — read more than we can possibly integrate into our lives.

We consume actionable articles and actionable books, practitioner podcasts and practitioner tweets, productivity newsletters and how-to videos. We read much more than we can feasibly test in a given week.

Two years ago I wrote a summary of Cal Newport’s Deep Work, with the expectation that I would test every idea in the book and then write a post with notes from that experience. As of today, I still haven’t finished experimenting with all of the book's ideas — I’ve only tested enough to conclude that Deep Work might not apply perfectly to professions outside academia.

Beginning to think that Cal Newport's Deep Work should be read with the qualifier: "written by an academic, in a field where deep work is disproportionately rewarded; may not apply if to other professions."

— Ced (@ejames_c) July 19, 2020

That isn't to say it isn't valuable. Just that you should be careful.

That was a rather epic failure on my end. The ideas from Deep Work remain in my ‘to-experiment’ backlog; it is unclear if I'll ever get around to finishing them.

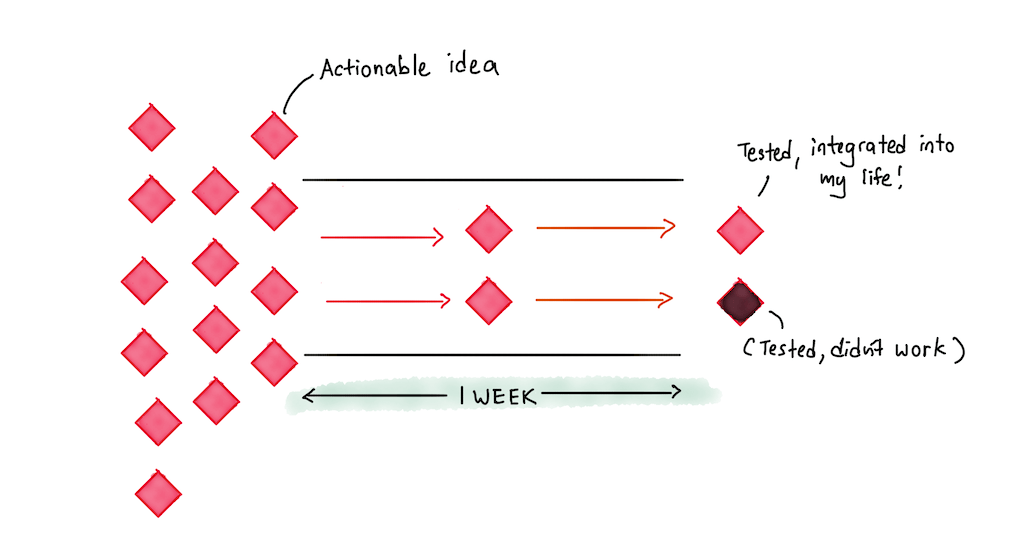

I’ve begun to notice that I’m limited to two self-improvement experiments a week. Two a week — that’s it. Two slots don't make for much throughput. What makes things worse is that certain experiments take longer to conclude — when I was giving Andy Grove’s High Output Management a go, for instance, I remember taking a month on average to put each chapter to practice.

If we put this observation together with Forte’s series on the Theory of Constraints, then I think it’s pretty clear that I’m suffering from a form of bottleneck:

Everything that I can’t put to practice accumulates as inventory in a note-taking app somewhere. It takes up space. It produces busy-work. And I often don’t get around to it — at least, not as much as I want to.

So as with production, I have two options:

- I can find ways to increase the number of self-improvement tests I run in a single week, or

- I can reduce the amount of actionable content I consume.

The second idea is easier to do than the first.

An Exception

One exception to this idea is if you are reading to build a library of patterns in your head (I’ve written about this practice here). With pattern building, the more patterns you have, the better your analysis. So there really isn’t a bottleneck here — you can fill your pipeline with as many history books or business biographies or annual reports as you wish.

This exception makes my previous observation a tad more nuanced: I am free to fill my pipeline with narrative non-fiction, so long as I limit the number of actionable sources I consume in a given week.

This seems like a far more sustainable mix for my ongoing reading programs.

Wrapping Up

If you read Forte’s work closely enough, you’d realise that one of his core values is to focus on outputs above systems. The basic idea is that you want your outputs to drive the demands on your productivity systems, not the reverse. In a 2017 interview with Evernote, for instance, Forte says:

People come up to me, sometimes, and their initial entry will be, “I don’t like productivity because it’s about being efficient, and like a machine, and just sticking to the plan.” And I just go, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. What’s your definition of productivity?” And they tell me something like, “Oh, what machines do, basically.” And then I say, “Can I tell you my definition?” And my definition is creating as much value in the world as efficiently and as effectively as possible. And they go, “Oh, well, I can buy that.”

And that’s where creativity comes in. It takes immense creativity to use processes in that way. To not be a slave to the process, to not just obey the process, but to think, “This part isn’t working,” or to have the courage to say, “Look, this process we’ve always followed does not serve our purposes. It’s no longer in line with our values. Let’s change it.”

Let your outputs define your processes, or better yet, let your values define them. I like that; I think it’s a pithy idea, and I think the spirit of Tiago’s ideas are worth exploring, because he’s tested them for years. When applied, it means to only invest in a system if you think your outputs aren’t where they need to be. And it means to read only as many actionable books as you can reasonably put to practice in a given week.

I’m going to give this a couple of months; I’ll let you know how it turns out.

Note: I've written an update to this post here →

Get the Action Sheet

Download the actionable summary for Consume What You Can Do here →

Originally published , last updated .