Note: this post is a follow-up to last week's summary of the strategic theories of John Boyd, and leans rather heavily on some of the ideas in that essay.

Let us pretend that you are a laminate manufacturer.

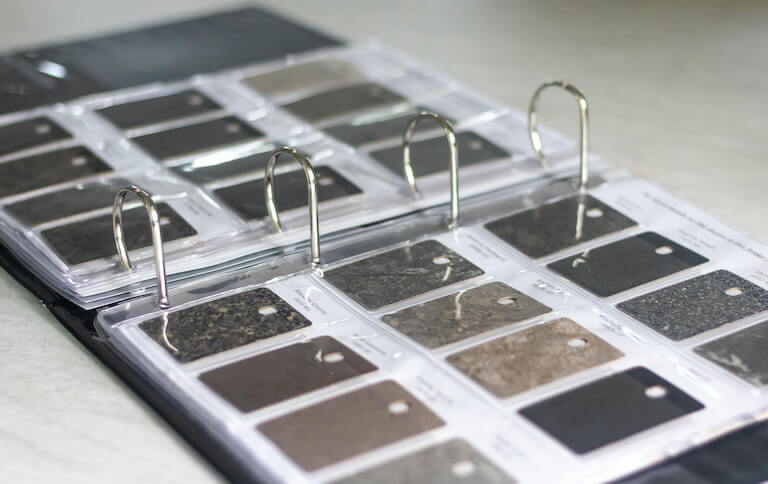

In case you don’t know what laminates are: laminates are a surfacing material that is used to trick people into thinking that they are looking at wood or metal or stone. You’ve probably seen them if you’ve spent any amount of time in a fast food restaurant — in fact, the odds are good that at least one surface in your house right now has a laminate top.

Laminates are a composite material: it is made up of several layers of paper, a colour sheet, and a clear melamine overlay. The layers are saturated with a resin (think of resins as a glue, with an equivalent drying time known as a ‘cure time’) and are then compressed in large industrial presses under great heat and pressure. Decorative laminates rose in popularity in the 50s, and remain one of the most inexpensive surfacing materials on the market today.

Let’s say that you fell into the laminate manufacturing business near the beginning of the boom, and you rode the growth of the laminate market to become market leader. For awhile, all was good. Then, one day, you notice that a small competitor has crushed all the other tiny competitors, and has begun to gain on you.

You do not notice this immediately, of course — the first time you hear of it, your head of sales mentions, as an aside, in the middle of a conversation about something else: “… so we’ve been losing distributors and customers to Bob’s Laminates, that tiny company from the South”.

“How many?” you ask.

“About a hundred significant ones have defected over the past two years or so,” he replies, wrinkling his nose. You do a quick count in your head: 100 isn’t much; you have about 3000 customers overall and about 65% market share.

“At first we thought it was an aberration.” he continues, “Just a couple of distributors switching from us — you know, the normal give-and-take of business. And BL was relatively new to the market. But we’ve been trying to get those customers back by offering them bulk discounts and price cuts — that’s what I asked for in our last quarterly meeting — but it doesn’t seem to be working.”

You nod your head and mutter something about keeping an eye on the situation, and then you go back to work.

It’s another two years before you realise that something really bad is going on — in that time, another 200 or so customers have switched, and none of them have switched back. You haven’t been ignoring Bob’s Laminates totally, of course: you took notice when BL got bought by a conglomerate; you also began to worry as they used the conglomerate’s cash reserves as growth capital to expand their factories and their delivery network.

For a little while, you could set the BL threat to one side as you focused on the work of running your company, but this year is the first one where it’s clear that your revenues are affected by their activities. The overall growth of the market for decorative laminates has stalled, which means that BL’s growth is beginning to eat into yours (they had been eating into the other minor players for years at this point). Noticing this, you corral your executives into a room and demand that they get answers. “And make this your top priority!” you say.

Your team goes off to gather intel: some of them hunt down the distributors and customers who have switched, others sniff around BL’s supply chain to see what’s up.

The information that comes back is completely bizarre.

First, BL produces products that are of equivalent quality to your company’s products. And in fact their product lineup is different only in superficial ways — they have certain designs that you do not have, and you have certain designs that they do not have. When they first arrived on the scene a decade ago, BL had a tiny product line, and no economies of scale. They sought to differentiate themselves by guaranteeing a 10 day delivery for their laminates. This fact was why you ignored them in the beginning: BL was forced to expand their product line aggressively to match yours, putting large capital constrains on their business. You note how they’ve caught up in the years since; today, both your company and theirs are putting out new patterns and new finishes at about the same rate. There is no clear advantage in either company’s product lines.

Second, their products are more expensive compared to yours. This is odd, and it makes little sense to you. Somebody in the sales department manages to get their hands on enough old BL catalogs to put together a picture of the price changes over time — the catalogs tell you that BL’s prices had always been higher than yours, but about five years ago, BL started increasing their prices — something that they’ve kept up in the years since. At this point you estimate that BL’s gross margins are higher than yours, assuming equivalent costs — and they’re taking away market share from you with a more expensive product.

Something doesn’t add up.

Third — and this makes you scratch your head even more — none of the customers who had switched over the past two years were willing to return! This was despite repeated price offers from your sales team, and despite renewed campaigns from your marketing people over the equivalent period. “This is ridiculous!” you say, and your head of sales nods vigorously. “Have you talked to any of them?”

Your head of sales tells you that he’s talked to about 30 customers who’ve left you, and that all he got out of it was that a couple of them said “Yeah, we like you guys, but BL delivers their laminates within 10 days of our order, like clockwork. They’re great.”

“And that’s even after you offered a 30% discount on their next five orders?”

“Well, they said they’ll think about it, but they never got back to me.”

“Well, these are all local distributors, right?” you say. “Maybe they’re too busy.”

“Maybe.”

“So let me get this straight,” you sigh, “We’re larger than BL, we have economies of scale, and we produce an equivalent product for a lower price. You’re telling me that superior delivery speed makes that much of a difference?”

“First, superior delivery speed to anywhere in the country. But yeah, I don’t know. Maybe there’s some special deal BL is cutting with them. It doesn’t make sense.”

There’s a pause.

The head of sales scratches his nose. “Well, maybe, I think it’s worth giving it a shot, no?” he says, “If the customers want fast delivery times, maybe we should give them fast delivery times?”

You tell him you’ll think about it.

Finally, you hear back from your supply chain people: BL orders many of the same resins that you do, but they also order particular resins that are much more expensive than yours. In some cases, you hear, BL had requested for special resin formulations. For those formulations, they paid higher prices.

You look at the price list from the resin supplier and do some quick sums in your head; you realise that at your prices, you cannot afford to use some of these resins. But perhaps this explained the price increases in BL’s product line.

“Why are they asking for special formulations?” you say, and your subordinate shrugs: “My contact at that resin supplier said BL wanted resins with a particular cure time.”

You pepper your subordinate with more questions but he can’t give you more than that. You let him go after an hour of talking, just thoroughly confused.

This is What Uncertainty Looks Like

This somewhat fictional account captures what it feels like to run a business under normal conditions — that is, under conditions of uncertainty. You never really know what your competitor is up to, you can’t observe them most of the time, and the results of your decisions and the impact of their actions take months before they become clear to you.

You can sort of squint here and see how this is similar to war, which was what the military strategist John Boyd was concerned with. Or how it is similar to the uncertainty of navigating a career move. You can look around at the global pandemic and map your feelings about planning ahead in your life to the things our fictional CEO feels when she is asked to come up with a response to Bob’s Laminates.

Coming up with a response is difficult for many reasons. It is difficult because we do not know why BL is winning. It is difficult because BL is taking market share away from us for every day we spend thinking. And it is difficult because none of the observed facts we have matches the analytical frameworks that are present in our heads.

With this, you can sort of see why Boyd makes analysis and synthesis the center of his theory. In adversarial competition, your actions are limited by your sensemaking ability. Here, we have a handful of observations about a developing situation. The longer we wait, the more our position erodes, and the less options we have available to us.

How do we make sense of the situation? We don’t have ready-made frameworks to do analysis with — the usual suspects of ‘lower prices beats the competition’ and ‘economies of scale available to the market leader leads to lower costs and therefore lower prices’ don’t seem to apply here.

It seems that what we need to do is to gather enough information to synthesise a new explanation instead. And this is where our problems begin.

Analysis and Synthesis, Again

In my summary of Boyd’s ideas last week, I wrote:

… there are really only two modes of thought when you are sensemaking. You either take a framework and apply it to a situation, organising the facts to fit your desired narrative (analysis/deduction), or you take the facts as they are and build up an cohesive explanation for why they are the way they are (synthesis/induction). Anyone who has spent any amount of time writing a college term paper would be familiar with these two modes of thought.

Boyd argues that a smart strategic thinker (and a smart thinker … of any kind, really) must do both.

The reasons for this is simple: adversarial competition of any kind is a dynamic system between multiple actors. The very instant you form a mental model of the situation, you will make decisions and take actions, and therefore change the situation that you have observed. Getting stuck with one conception of the battlefield is a surefire way to be overtaken by the natural uncertainty of war (or be taken advantage of by a savvy enemy who is able to exploit your now static orientation).

Instead, Boyd argues that good strategic thinkers are able to destroy their mental models, and then recreate them either via analysis or synthesis, and repeatedly cycle through these two modes of thought as new information presents itself.

What I left out in my piece was the idea that analysis and synthesis is also required when you are faced with an environment that has changed in ways that you do not understand.

This could be due to a global pandemic. Or it could also be — in the words of legendary CEO Andy Grove — when you face a ‘strategic inflection point’ in your business or your career.

Of the two activities, I find synthesis the more difficult one.

Analysis is relatively easy: you take some framework and you apply it to your situation. Or — if it is not so easy to apply a framework — you ask smart questions, and break the domain down into smaller pieces to reason about. In the story above, our intrepid CEO was doing exactly this — we watched as she tasked her team to gather intel, to break the problem down to individual domains for further investigation, to recompile all the findings, and then — right before we left her — we watched as she struggled to make sense of it all.

Analysis is easy, but synthesis is difficult. Synthesis isn’t commonly taught in schools, and so usually we have less experience with it. Another way to describe this sort of thinking is to say that it is functionally equivalent to ‘inductive reasoning’ — that is, the act of coming up with some general truth from a set of observations. For instance, if we have only observed white swans, we may reason that only white swans exist. This does not guarantee that this is true — indeed, we know today that black swans hang out in Australia. But inductive reasoning gives us a hypothesis to investigate — and more importantly, it gives us several implied predictions that we may test.

Synthesis is difficult because it demands original thought. It asks that you take in everything that you see, and find some organising principle to explain the big mess of observations in front of you. It demands that you come up with theory from scratch.

What The CEO Did

Boyd argues that if you are successful at synthesis, your next step is to test it, that is: to begin looking for a) internal inconsistencies, as well as b) mismatches to reality. A working model of the situation is only useful if it is internally consistent and if it matches up with what you observe. More importantly, your model should match up with what you expect to happen when you act.

The instant your observations no longer hold up, it is time to switch to analysis again.

So what may we synthesise out of all the observations we have seen alongside our intrepid CEO? I think a couple of possible hypotheses fall out of the story:

- Delivery time really does matter to these customers, and we should find out why it matters so much.

- Perhaps BL really isn’t doing anything special; perhaps they were cutting some deal with the customers they’ve successfully lured away, and covering the costs with the cash reserves from their parent company.

- Perhaps there’s some other angle that we haven’t yet seen, and we should hunt for more information. Perhaps it might be worth it to talk to one of the minor competitors that BL put out of business?

Let’s put you back in the CEO’s shoes again. You think about your hypotheses and you reason the following:

- If BL were cutting some special deal with their customers, why are they willing to spend extra on specialised resins? This makes hypothesis 2) less likely. Also, assuming that they are irresponsibly spending the parent company’s money is a bit of hopeful thinking — it is more useful for you to assume competence instead.

- Hypothesis 3) is likely — you don’t know what you don’t know, after all — but you’re running out of time.

- Your best bet is to investigate hypothesis 1 and then reorient rapidly if it turns out to be a dead end.

There are a couple of things that you can do to test your hypothesis. The first is that you may look to see if the customers who have left you fit a certain profile. If they do, then you may predict that the next couple of customers to leave you would also fit that profile. Plus — you reason — if there is a profile, maybe that profile would help you figure out why this segment is so time sensitive in the first place.

The second thing you can do is to ask customers why they find the 10 day delivery so compelling. You know your head of sales has already done some asking of his own, but you intend to ask “why” until you get a compelling answer — that is, an answer powerful enough to explain their behaviour of forgoing your reduced prices.

The third thing you can do is to run a test — to see if it’s possible to match BL’s ten day delivery in a certain subsegment of your market. This is going to take longer, of course, but it would provide stronger evidence to you if you can arrest BL’s advance in that particular region.

So what comes of it?

It is the second thing that provides results first. You get a list of ex-customers from your head of sales, and it takes a few calls before one of them explains it to you:

“Look, if I order from you, you usually deliver 10 days, 20 days, who knows? It’s not consistent. I can’t have my customers waiting on me! So if I buy from you, I have to maintain an inventory to prevent overlong waits from happening. And because there are so many goddamn laminate SKUs today, who knows what the clients want? I’ll have to keep a huge amount of inventory on my end! That’s cash that’s locked up and not seeing the light of day!”

Another distributor explains: “With BL, my inventory turns are much higher because I store so little. I can just rely on their 10 day delivery guarantee. That’s good cash flow that I’m giving up if I go with you, even though you offer me lower prices!”

You assign Bob and Sam, two fresh-grad MBAs, to look into the first thing for you. They come back a month later and say that they’ve figured out the personas that are responding best to BL’s value proposition.

“What are they?” you ask eagerly.

Bob and Sam throw up a powerpoint presentation, just like they were trained to do in b-school. You learn that there are, roughly speaking, three personas in the laminate market, and two of them are the reason for distributors switching rapidly to BL:

- The Residential Cabinetmaker. This customer usually operates out of a small shop, serves a local area, and is undercapitalized. When the customer chooses a decorative laminate, the cabinetmaker goes to a distributor to get the sheets needed. This persona expects the distributor to stock all the laminates he or she might need and to sell them at a fair price, though not necessarily the lowest price. The cost of the decorative laminate for most jobs is less than 33 percent of the total price of the job with the rest of the costs being for wood, hardware, and labor. Successfully serving this customer means availability first, and then good prices.

- The commercial specification customer is an architect or an interior designer. These people chose decorative laminates to enhance the visual appeal of their projects, for example to simulate the look of Italian marble in a hotel bathroom. Choice and merchandising are more important to these designers than is price because the costs of the decorative laminates are a very small portion of the total costs of the projects.

- The OEM direct purchase factory. These factories are the scaled up version of the residential cabinet-maker. They manufacture a wide range of furniture — cabinets, table tops, display cases, and the like. Since they operate at scale, they buy direct from you, with limited selections, and at high volume in order to keep costs low. These customers have not switched away from your business.

And so now you finally understand what is going on. Your distributor customers primarily served the first two segments, and they realised over the past decade that their customers weren’t particularly motivated by price. If they switched most of their offerings over to BL, they could keep their inventory costs low, and increase velocity. This meant better cash flow overall, despite the higher prices from buying BL products. (In practice, they lowered their prices thanks to their improved cash flow position to capture more business, thus increasing velocity even more). On the flip side, OEM manufacturers were motivated by cost considerations, and so they continued to stay with your company due to your lower prices.

With this orientation, you can now begin to reason about responding to BL.

Alright, let me skip to the end here and tell you how I came up with this story.

Is this story real? No, of course it isn’t. But is it based on a real story? Yes: in the 60s, Ralph Wilson Plastics stumbled — by accident! — onto a competitive advantage against Formica, the market leader. Dr Wilson originally made the 10 day promise because he believed in good customer service above all else; as time passed, the management team at Ralph Wilson Plastics began to realise that time was an advantage they could wield against their competitors, due to the unique makeup of their market.

RWP began investing in manufacturing processes that optimised speed above all else. The example of the custom resin formulations is instructive: normally, different resins would have different cure times. RWP standardised all its resins to have the same cure times, in order to reduce the complexity and increase the tempo of their manufacturing processes. They could justify the use of such expensive materials because they charged higher prices than pretty much everyone else; the net result of this fight was that RWP grew 3x the industry average, and had profits that were 4x the industry average. They caught up to Formica to become second place in the laminates market within two decades.

How did Formica respond to Ralph Wilson? The exact internal conversations they had are probably lost to time. But what we do know is that Formica continued their low cost, market-leader positioning for years afterwards. Why didn’t Formica retool their factories for speedy delivery? The answer might be that OEM manufacturers — while less profitable to serve because of their price sensitivity — made up the bulk of the market. Formica was perfectly happy to defend its OEM business; they couldn’t pivot to take back the distributor market as effectively because that would mean adopting higher costs in both manufacturing and distribution.

What is the general form of this strategy? It is that speed of value delivery can be used as a competitive advantage, in a variety of scenarios: for instance, if you operate in a market with time-sensitive customers, or if your market rewards incremental innovation. (The Hamilton Helmer 7 Powers framing of this idea is that time-based competition draws on ‘process power’; it is difficult for a competitor to reorganise in order to achieve speed).

How do we know the general form of this strategy? The answer is that a few consultants from the Boston Consulting Group noticed several commonalities in some of the companies they were advising during the 80s. In 1989, George Stalk Jr of BCG published Competing Against Time, from which this story is taken. The general theory of using speed as a competitive advantage was synthesised from observations of the competitive dynamics around Ralph Wilson Plastics, Toyota, Hitachi, Sony, Atlas Door and a couple of other companies besides.

Good Synthesis, Bad Synthesis

What is the point of this piece? I have attempted to show how it feels like to synthesise in the face of uncertainty. But I have also shown — I hope! — how difficult it is to synthesise an effective model under real world conditions. Remember that Formica was defending itself against RWP in the 70s, and that the ideas in Competing Against Time was only synthesised in the 80s. I am not certain I could have come up with the explanatory model above if I were in charge of Formica. Instead, I would be lost, confused, and would likely be thrashing about as I watched my market share taken out from under me.

Apart from emphasising the importance of analysis and synthesis in strategic thinking, Boyd only gives us two prescriptions when going through the analysis-synthesis loop:

- Your synthesised model must be internally consistent.

- Your synthesised model should match observations of reality.

Violate any of the two, and you should destroy your mental model and drop back down to analysis.

This is a lot easier to say than to do. I think there’s something here about the human brain that makes us hold on to our sensemaking patterns, long after they have outlived their usefulness. If you’ve spent any amount of time reading business biographies, you would likely spot instances of business people holding on to their old models of the world, refusing to accept the signals that tell them the world has changed outside the firm.

And so if there’s one takeaway you should have from this piece, it is the difficulty (and importance!) of successfully synthesising from chaos, and then successfully destroying those synthesised models, repeatedly. This is true regardless of whether you are running a business or attempting to build a career moat.

There is one last point I’d like to make about synthesis, and this has to do with the bad bits.

The results of synthesis is a sensemaking pattern, or framework. I’ve noticed that synthesis is what draws us to certain writers or thinkers (imagine the relief the Formica leadership might have if you had gone back in time to give them Stalk’s book!)

But this is also true when it comes to online writing. The most popular articles on this blog, for instance, are the ones that give readers an organising framework for something that they’ve already experienced in their lives. Take The Three Kinds of Non-Fiction Books as an example. It is one of my more popular posts, because multiple readers find it a useful organising framework for the books they’ve read in the past.

But if sensemaking patterns are what we look for as readers, then we should expect authors to optimise for it — regardless of whether their synthesised patterns are true, or useful. In Beware What Sounds Insightful, I warned against reading online writers uncritically, because they are likely to have responded to the incentives for attention capture.

I realise now that one way to appear insightful is to synthesise freely — never mind if the resulting pattern is not internally consistent, or if it doesn't match what occurs in real life. Rely on the human desire for sensemaking to grow your audience.

Boyd’s ideas suggests something neat: the next time you read an author that attempts to synthesise a general pattern from a set of observations, evaluate according to internal consistency, and then generate possible counter-examples. For each counter-example you find, mark the author down for synthesis.

If you want to adapt quickly to uncertainty, you can’t really afford to walk around with outmoded models in your head. The good news is that Boyd gives us an idea of what to do; the bad news is that it’s still really really difficult. But I suppose that’s just the way it is.

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Market topic cluster, which belongs to the Business Expertise Triad. Read more from this topic here→