This is Part 3 of a series on business expertise. Read Part 2 here.

One way of looking at Lia DiBello’s extracted mental model of business expertise is to say “oh, so this is what business expertise looks like, I can go find concrete examples of this now”

This interpretation is, I think, rather important. Even if you can’t benefit directly from DiBello’s training interventions, you can keep an eye out for examples of business expertise to study and emulate.

I want to talk about some second-order implications of this, at least when it comes to the expertise we’ve covered on this blog in recent weeks. I think that knowing the shape of expertise in a domain is useful, even though it’s not as clear-cut as having a proven training program for that expertise.

It just demands that you do a bit of work.

Learning Business in the Trenches

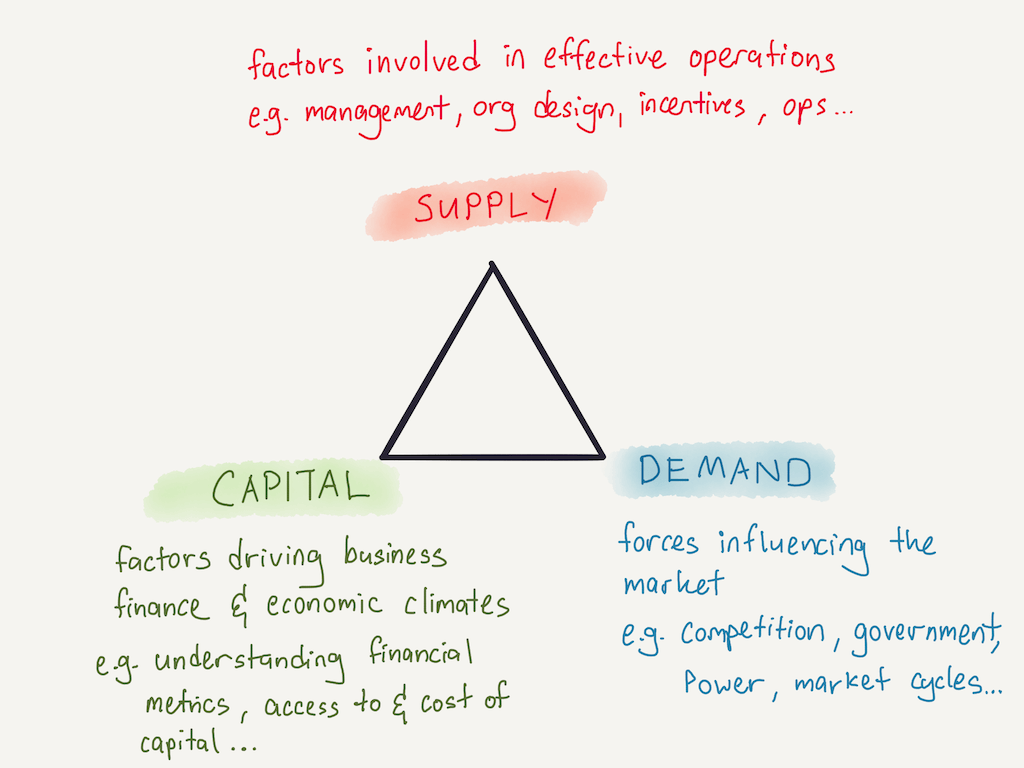

We’ve talked a lot about DiBello’s mental model of business expertise in the last couple of weeks, but let’s do a quick recap. According to DiBello, the extracted mental model of business expertise consists of two bits: 1) a triad mental model of supply, demand and capital, and 2) a psychological construct called cognitive agility.

I think certain longterm readers of the blog might have found it surprising that I accepted the triad mental model with comparatively little scepticism. On reflection, I think DiBello’s work simply confirms something that I had been moving towards for a few years now.

I’ll give you some background to explain what I mean.

Most people who start out in business start out by learning the Supply side of the triad. This is especially true if you are brought in as an early employee — as I was — or if you are put into more operational roles, as opposed to more customer-facing ones. These early company builders grapple with the sheer difficulty of growing a business — the challenges of building product (or finding a thing to sell), and then of hiring well, of learning to manage people, of designing an organisation and its incentives so that the company is able to deliver its products or services reliably to its customers.

It’s not too long after that that people begin to bump up against the Demand side of the triad, though. If you’re a founder, you probably have to worry about Demand from the get-go, but from experience, most people don’t think about the implications of market competition until much later in their business lives. It usually takes a number of years before you realise that “oh, wow, competitive arbitrage is a thing — over a long enough period of time, competitors will cut prices and bring my margins down to the opportunity cost of capital. Huh.”

It takes a little longer still before you realise that certain companies can resist margin compression, and others cannot — eventually, everyone who is proficient at business builds an intuitive sense of ‘moats’ — and may discover that there are really only seven forms.

I think what I’ve described so far is a pretty good description of business education from the trenches — the sorts of experiences that you get when you’re actually running a company. Even in the early years of my previous role I joked that what we did was half ‘internal’ — figuring out how to keep star employees; dealing with internal mishaps as they emerged — and half ‘external’ — figuring out how to beat competitors in deals; fighting for market share. This mapped pretty neatly to ‘Supply’ and ‘Demand’.

As it turns out, this duality of internal and external concerns maps pretty well to most startups — and I’ve noticed that the majority of early business mistakes tend to fall into one of the two categories. If you’ve been in startup land for a bit, you’d likely have heard stories where the company is so badly run that all the early employees quit en-masse. And who hasn’t seen a company fizzle out as they fail to achieve ‘product-market fit’?

A year after I left my old role, I began systematically working my way through a large set of business biographies, due to a (mostly validated) belief that it would help me see a broader set of business patterns. The more I read, however, the more I began to notice that there were a whole bunch of moves that didn’t exactly belong to Supply or Demand. Yes, more often than not businesspeople won by successfully meeting market demand and beating out the competition, and yes, more often than not businesspeople got good at running their companies. But the more sophisticated the business, the more likely you would find a savant who would do things that didn’t fit into any of those buckets.

These moves are more appropriately described as ‘Capital’.

My goto example is John Malone’s TCI, which I wrote about in The Games People Play with Cash Flow. Malone was amongst the first in the cable industry to have discovered junk bonds, and to realise the implications of debt on company structure (Supply) and company strategy (Demand). He realised that you could a) take on large amounts of debt at a certain ratio (Malone chose 5-to-1 debt-to-EBITDA), b) use this debt to acquire cable companies, c) use the monopoly cash flows from those cable companies to service the debt, d) use the debt and the depreciation from cable equipment as a tax shield for those cash flows, and finally e) grow so large that you could amass real power; in his latter years Malone demanded equity from cable channels in exchange for subscriber access, and these equity stakes began to appreciate massively in the late stages of the cable industry boom.

None of these manoeuvres may be accurately described as ‘Supply’ or ‘Demand’ (though Malone had his deputies run TCI as a tight ship). And yet they led Malone to take an outsized position of influence within the cable industry over a period of 25 years.

More recently, Michael Dell used a similar Capital playbook to finagle control of his namesake corporation:

Dell has been publicly quiet for most of the past decade, muzzled by fierce takeover negotiations or simply uninterested in the spotlight, or both. His business has done the talking instead. Nine years ago, Silicon Valley and Wall Street alike had written off Dell, the person and the company, both tethered to the then-cratering personal computer market, as en route to the same technological irrelevance as Palm or BlackBerry. Yet even then Dell saw opportunity: He enlisted private equity firm Silver Lake and its billionaire co-head Egon Durban to sidestep the public cynicism, taking his company private for $24.9 billion in 2013, the largest technology leveraged buyout ever. Three years later, he and Durban conjured $67 billion to engineer the acquisition of IT infrastructure giant EMC Corporation. In all, Dell piled an astronomical $70 billion in leverage on his empire, shovelling on debt unlike any thing ever witnessed in corporate America.

Malone had a hand in this deal, too — when Dell attempted to purchase EMC, the dealmakers turned to Malone for advice on issuing a tracking stock for VMWare (VMWare was held within EMC, and seen as a highly valuable asset; Dell used the tracking stock as collateral to finance the purchase). The move allowed Dell to acquire EMC for far less cash than it otherwise had to.

Of course, Dell’s moves were only possible because EMC and Dell Technologies were both undervalued by the public markets, despite having solid B2B businesses with strong cash flows at their centres. So it’s not as if Dell wasn’t a savvy player on the Supply or Demand legs of the triad — he was no stranger to OEM company operations, and he understood where the corporate IT market was headed. But my larger point is simply that if you see business as purely ‘Supply’ and ‘Demand’ — or ‘make a widget and sell a widget’ — you would struggle to explain this set of moves as part of the overall business toolbox.

DiBello’s extracted mental model merely confirms for me that business consists of more than just ‘internal, operational concerns’ and ‘market understanding’. It also consists of financial savvy. Before I found her work, a friend asked me why I was so interested in capital structure, and why I read so much finance, given that I was an operator and not an active investor. I couldn’t articulate a coherent response at the time. The only thing I could say was that I thought it afforded a third path to competitive advantage.

But now I have a better response: I can say that the shape of business expertise is a triad; Capital is simply the leg that is most opaque to the novice operator.

How To Use This?

What can we do with this understanding of the shape of business expertise?

One implication is that we should decompose stories of business operators into the three legs of the triad. This is surprisingly fruitful — recently, I went back and reread Robert Kuok’s biography, but through the lens of Supply, Demand, and Capital. I did so because Kuok operated in a region of relative under-development and at a time with very little access to capital. His story decomposes well — he was a good employer who learnt to give shares to his employees fairly early relative to his peers; he made mistakes playing in more complicated commodity markets when he was starting out (‘running plywood mills was one of the most excruciating experiences in my life’) before learning to partner up when moving into more complicated businesses such as hotels; he described the competitive dynamics of moving from Johor to Singapore, partnering with Indonesian magnates, and then moving to Hong Kong. Most interestingly, he had to struggle with unfriendly foreign banks (who discriminated against colonial subjects) and then spotty government financing in the early decades of his career.

I’m currently looking forward to reading other business biographies through the lens of the triad. I think it might be interesting to see how it is expressed with different businesspeople and in different industries over the course of history. I’ll tell you how that works out.

A second implication that I’m taking away from the triad is to evaluate my skill in relation to other businesspeople through all three elements. In my head, a tentative skill comparison goes something like this:

- What are the operational factors involved in running a business in this industry, and what am I lacking? (To be fair, I think that I’m better off on this leg than most, at least when it comes to B2B software).

- What are the factors influencing the market for the market I’ve chosen to play in? What do my competitors understand that I do not?

- What are the financial metrics and capital climate for this particular business? What do my competitors or peers in adjacent markets get that I do not?

- And can I predict how changes in each leg affect the other two, at least for my specific industry?

This very formulation of business skill tells me that I have years to go before getting decently good at all four questions. The breakdown gives me a way to evaluate my competitors and my peers — and to pick mentors for skills that I do not currently have.

Sure, it isn’t as good as a training syllabus. But a North Star is better than none.

Appendix

Quick note: In this piece I’ve mostly focused on the three elements of DiBello’s triad mental model as a static shape, but I should emphasise that the expertise is expressed as an intuitive understanding of the relationships between the three nodes for a specific industry, not merely skilful application of each leg. As DiBello puts it herself:

I love the drawing! Truthfully, you can meditate on this triangle for years before realizing that it's the living dynamic between the nodes that matters. E.g., demand goes down, it instantly changes the opportunties/constraints in the other two.

— LiaDiBello (@LiaDiBello4) August 15, 2021

Originally published , last updated .

This article is part of the Expertise Acceleration topic cluster. Read more from this topic here→