Commonplace is about building career moats, and I've spent the last couple of months writing up notes on this topic. Career moats happen to be an obsession of mine; it is the primary lens with which I think about my career.

This is a summary of everything I've written about career moats so far. I intend to keep this post constantly updated, and linked from this blog's main sidebar, in order to always be accessible to new readers.

First, what is a career moat? I've got a dedicated page for this, but in a nutshell:

A career moat is an individual’s ability to maintain competitive advantages over your competition (say, in the job market) in order to protect your long term prospects, your employability, and your ability to generate sufficient financial returns to support the life you want to live. Just like a medieval castle, the moat serves to protect those inside the fortress and their riches from outsiders.

The central thesis here is that career moats are worth pursuing because we live in a world of constant change. What is valuable today might not be valuable tomorrow, and the constant threat of automation and globalisation means we are no longer guaranteed careers (or company-supported retirement!) in the modern economy.

This is a depressing outlook — but it is, I think, the state of the world that we live in. It's doubly depressing if you consider the full implications of this worldview: that not building a career moat means living in constant fear of dropping off the bandwagon.

In a sentence, then, a career moat is worth building because it buys you time when your job or career is threatened by an emerging industry change.

What Does a Career Moat Look Like?

It looks like this: you aren't that worried about finding work. You know that if you are ever laid off, you may easily find another job, because you possess ‘career capital’ — that is, skills that are relatively rare, and are in sufficient demand to guarantee a base level of compensation to support you and yours.

This knowledge gives you peace of mind. It allows you to think more strategically about your career, and it allows you to plan your moves ahead of time.

To put this another way, job security is tied to your ability to get your next job, not keep your current one.

The ‘moat’ in ‘career moat’ comes from the safety this knowledge buys you.

I practice what I preach; the most important goal of my early career was building a career moat. Having this moat allowed me the peace of mind to leave my job in order to attempt a business of my own; I knew that if things failed, I could always return to employment. (I've covered this episode in my blog post Building Career Moats: A Confession).

And after watching the careers of my peers, mentors and seniors, I believe that a career moat is often the best position to go after — or at least, the best first position to pursue.

I know of only a few people in my direct circle who have achieved such a position. But I've noticed that the downstream effects of having a career moat is so powerful that it makes going after a moat an ideal position to be in: your skills are so evidently valuable and comparatively difficult to find that people are constantly looking to poach or recruit you. You know your edge and are able to look for companies that are in demand for your skillset. And you're able to focus your job search along specific parameters because you know the sorts of companies that will pay you best for your skillset.

As Cal Newport puts it, if you focus your efforts on gaining rare & valuable skills in the first part of your career, you may choose to trade it for autonomy or purpose later.

What Does a Career Moat Consist Of?

A career moat consists of rare & valuable skills. This sounds like a ridiculously simple statement to make, but working out the full implications of this statement leads us to some really interesting places.

An obvious first implication is that anything taught in a course may be valuable, but it won't be rare. Therefore, undergraduate and masters degrees do not give you a career moat. In fact, there is research that suggests education merely serves a signalling effect to potential employers — which would then imply that degrees are a necessary but not sufficient requirement for building a career moat.

Career moats come in many forms. One way you can build a career moat is to be the ‘best’ in a specific, valuable field. For instance, software engineer Jeff Dean is widely recognised to be amongst the ‘best’ software engineers in the tech industry; he — along with longtime peer Sanjay Ghemawat — is famous for building many of Google's internal distributed systems. (See: MapReduce, Spanner, Bigtable, LevelDB, TensorFlow). It is undeniable that Dean has rare and valuable skills — the only way for him to lose his moat is for distributed systems to suddenly become irrelevant (an incredibly unlikely prospect in the tech industry).

Cal Newport further extends this idea in his book So Good They Can't Ignore You; he gives the example of television writers, standup artists, and musicians as careers paths where moats are built by being the best in their respective skill markets.

The other way of thinking about career moats is that you have a rare and valuable combination of skills. I examined this path in detail in my blog post If You Want a Great Career, Go After Rare & Valuable Skills. I gave three examples in that post:

- A skillset can be rare and valuable if the path to your unique combination of valuable skills is opaque. I gave an example of my friend in the telecommunications industry — his role requires him to be proficient in a broad set of rather unique skills, thus pushing up the lucrativeness of his specific job. (He has, to date, been poached twice).

- A skillset can also be rare and valuable if the skillset is unattractive but valuable. The rareness then comes from the majority of people being repulsed by the demands of the job. I wrote that COBOL programmers have such a career moat — many old banking systems are written in COBOL; not many new programmers know COBOL, therefore old-school COBOL programmers are sufficiently protected by this scarcity. This also happens to be my current career moat — as I documented in this post, my rare and valuable skillset is engineering management in uncomfortable, third-world countries. (Which is valuable at the moment only because of the existing startup dynamics of South East Asia).

- Last, but not least, a skillset can be rare and valuable if you specialise in it before it becomes clear that it is valuable. I gave the example of my friend who has staked out a position in AR/VR (Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality) user interface design; her bet is that AR and VR will become important computing interfaces in the near future, and she intends to be one of the leading practitioners by the time this happens. Such designers also exist in other fields — I am reminded of Jeffrey Zeldman, who made a name pushing web design standards back in the day, and Jakob Nielsen, who made a name pushing web usability research. Both of them established themselves before it was clear that their fields were important and valuable domains.

To be clear, I don't believe that only three paths exist; I think that there are many viable approaches to a rare and valuable combination of skills. This formulation is merely instructive because you may use it as a framework for evaluating career decisions.

When evaluating a potential career move, this framework suggests that you ask:

- Will this career move teach me skills that are rare and valuable?

- What skills are those, and how do I know that I will learn them?

- Is this skillset rare because the path to acquire it is opaque?

- Is it rare because it isn't yet clear that it is valuable? (Could an impending change cause it to grow in value over the next decade?)

- Is it rare because it is unsexy and painful despite being valuable?

- What are successful examples of people who have rare and valuable skills?

- If my goal is to be amongst the best in a skill tree, how confident am I that such a move will move me further along my chosen skill tree?

For further reading, here are the posts where I developed these ideas:

- A Summary of Cal Newport's So Good They Can't Ignore You

- If You Want a Great Career, Go After Rare & Valuable Skills

- Building Career Moats: A Confession

Strategic Inflection Points

How do you evaluate emerging career threats?

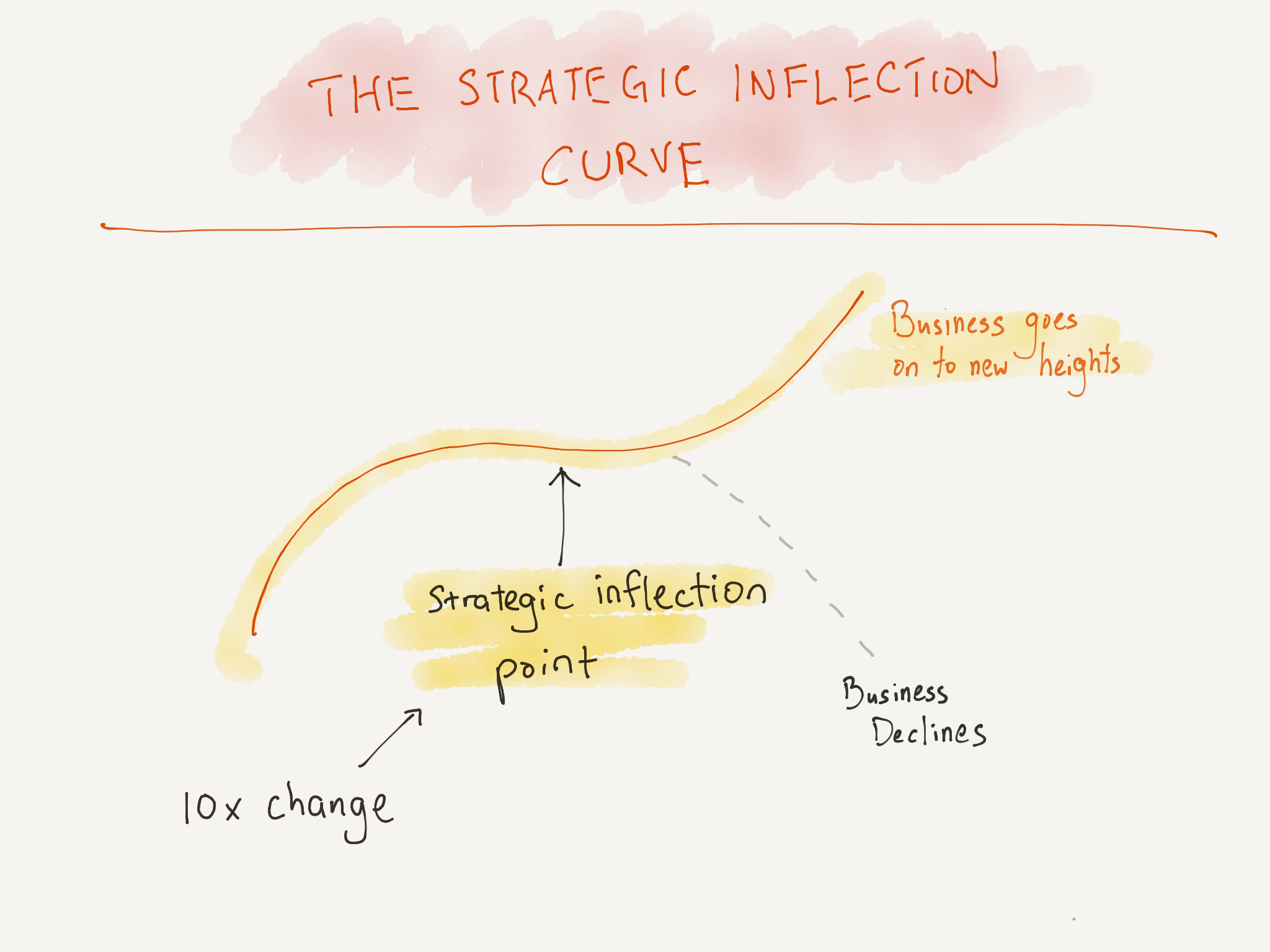

In his 1995 book Only The Paranoid Survive, Andy Grove wrote that it is the individual's responsibility to look out for ‘strategic inflection points’ — events that can kill businesses and careers — and to prepare for them well in advance.

Grove lays out a framework for thinking about strategic inflection points in his book, drawn from his experience running Intel, which I summarised in this post. In a nutshell:

- Don't fall for the trap of the bad first version when evaluating an emerging technology. Everyone laughed at the internet in the decade that it first emerged ... until it changed their careers, or disrupted their industries. This sounds trite and obvious in retrospect, but ask yourself: are you laughing at emerging technologies right now? Are you laughing at virtual reality, or augmented reality, or blockchain applications? If so, how do you know that you are right?

- Analyse the coming change by running through potential changes to the following relationships in your industry: does this emerging change affect the relationship between your company and its suppliers? Its customers? Its competitors? Its position with regard to new entrants? Does it affect the relationship between your company's product/service with its complementors or its substitutes?

- Store the observations you have of these six factors at the back of your head, and keep an eye on emerging developments as you go about your career. Update your observations whenever new developments occur.

I find Grove's approach to be far superior to other alternatives. You don't have to make accurate predictions of the future — you merely have to constantly update your knowledge of coming changes in a systematic, consistent way.

My summary of Grove's book may be found here.

How Does One Build a Career Moat?

The day-to-day reality of building a career moat is the same as building expertise in any field. These are relatively well-known approaches:

- Pursue rigorous, informed trial and error. Trial and error dominates in situations where a body of knowledge does not exist, such as in business and in life. This is because it lets reality be the teacher.

- Build the capacity for doing Deep Work in your life.

- Screw motivation, build habits. I recommend Stanford professor BJ Fogg's Tiny Habits course.

- When pursuing trial and error, remain in the game. Practice basic financial hygiene.

- Practice dominates because success is determined by tacit knowledge, what the Ancient Greeks called technê. (This is a truism — if success can be determined via explicit knowledge, we can all become successful through reading alone). Self-help is better understood through the lens of technê, which then leads to certain surprising implications about reading self-help.

- Beware writers who propose to teach you mental models without being practitioners themselves. (I call this the ‘Mental Model Fallacy’).

- Understand how humans learn. Know that you can't teach what they aren't ready to learn.

- When pursuing deliberate practice, recognise the difficulty of creating a DP-inspired training program. Recognise the differences between naive practice, purposeful practice, and deliberate practice. Pursue purposeful practice in domains where no established pedagogy exists.

- When reading self help, judge the advice according to believability and usefulness. Keep in mind the hierarchy of practical evidence. Evaluate advice according to the domain the author inhabits.

- Heed the academic literature around burnout.

- Read books to establish context for industry changes. Categorise non-fiction books according to these three categories; read quicker using these tips.

- If you are in a field that rewards the pursuit of side projects, use the techniques outlined in Amy Hoy's Just F*cking Ship to maintain a steady cadence of releases.

- Treat career moves as bets. When starting speculative projects, evaluate sub-tasks by information rate.

- Respect the human tendency to generate narratives, and use that to learn skills from more experienced people. When dealing with organisational politics, beware the simple story. Ask questions the right way, so you create a narrative of competence to present to your boss and colleagues.

Last, but not least, don't take anything I say at face-value, verify through practice and experience. Technê is only as good as practice dictates.

My path is still in flux, my journey is still ongoing. I may fail tomorrow in spectacular ways. But I hope what I've written has been helpful to some of you; I wish you the best of luck in your careers. Onwards!

If you enjoyed this, you might like updates on my articles over at the Commonplace Newsletter. Alternatively: I have two sequences I'm proud of over at The Chinese Businessman Paradox or The Principles Sequence — enjoy!

Originally published , last updated .